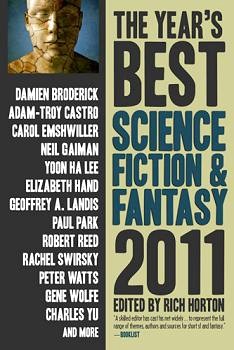

The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2011

The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2011

Edited by Rich Horton

(Prime Books, 2011)

“Flower, Mercy, Needle, Chain” by Yoon Ha Lee

“Amor Vincit Omnia” by K.J. Parker

“The Green Book” by Amal El-Mohtar

“The Other Graces” by Alice Sola Kim

“The Sultan of the Clouds” by Geoffrey A. Landis

“The Magician and the Maid and Other Stories” by Christie Yant

“A Letter From the Emperor” by Steve Rasnic Tem

“Holdfast” by Matthew Johnson

“Standard Loneliness Package” by Charles Yu

“The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window” by Rachel Swirsky

“Arvies” by Adam-Troy Castro

“Merrythoughts” by Bill Kte’pi

“Red Bride” by Samantha Henderson

“Ghosts Doing the Orange Dance” by Paul Park

“Bloodsport” by Gene Wolfe

“No Time Like the Present” by Carol Emshwiller

“Braiding the Ghosts” by C.S.E. Cooney

“The Thing About Cassandra” by Neil Gaiman

“The Interior of Mister Bumblethorn’s Coat” by Willow Fagan

“The Things” by Peter Watts

“Stereogram of the Gray Fort, In The Days of Her Glory” by Paul M. Berger

“Amor Fugit” by Alexandra Duncan

“Dead Man’s Run” by Robert Reed

“The Fermi Paradox is Our Business Model” by Charlie Jane Anders

“The Word of Azrael” by Matthew David Surridge

“Under the Moons of Venus” by Damien Broderick

“Abandonware” by An Omowoyela

“The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s Bellerophon” by Elizabeth Hand

Reviewed by Nader Elhefnawy

The latest edition of Rich Horton’s Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy anthology, Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2011, gathers together twenty-eight short stories from 2010. Between them, these pieces have reaped four Hugo, five Nebula, eight Theodore Sturgeon Memorial and three Locus award nominations – and one Nebula win. Additionally, seventeen made Locus’ Recommended Reading List for their year.

Where the original places of publications are concerned, sixteen of the stories – more than half –come from online venues (four each from Fantasy and Lightspeed, three from Subterranean Magazine, two from Strange Horizons, and one each from Apex, Clarkesworld and Tor.com), five from anthologies of original fiction (one each from Clockwork Phoenix 3, Songs of Love and Death, Stories, Swords & Dark Magic and The Way of the Wizard), and seven from print magazines (with three each coming from Asimov’s and the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and one from Black Gate). That the web is the scene of first publication for so much of the anthology’s material is noteworthy, an indication that this is increasingly the scene for short form genre writing (a fact that says as much about the economics of publishing as anything else, though it is an indicator of the growing respectability of web-published material). It is less surprising that a significant fraction of this Year’s Best comes from original anthologies, these having had a rising profile for a long time, but worth noting that virtually all their product comes from the fantasy genre, the science fiction appearing here instead coming from the other venues. The seven pieces coming from print magazines indicate that these remain a presence in the genre, albeit (much as some are loathe to admit it) a receding one.

It seems equally noteworthy that, while I often come to such anthologies hoping to see the web fulfill its democratizing promise by giving more obscure publications a crack at the big time, the web-published stories come wholly from the higher-profile online venues, web spin-offs of earlier print magazines like Apex and Fantasy, and publications noted for high pay and previous nominations for major awards, like Strange Horizons and Tor.com. Just as with the web stories, those originating in print come from anthologies overseen by Big Names (Jonathan Strahan, Lou Anders, Gardner Dozois, George R.R. Martin, John Joseph Adams, Neil Gaiman), and from the most-established magazines (like the three named above). As might be expected, Big Name writers like Damien Broderick, Neil Gaiman, Robert Reed, Peter Watts, Gene Wolfe and Charles Yu are prominent in the table of contents.

It is somewhat more difficult to offer a generalization about the balance between science fiction and fantasy stories here, because of the uses the stories make of those elements. A fair number of stories blend the style or substance of both those genres – or simply seem to defy easy categorization as either, terms like “slipstream” coming to mind on a number of occasions. Additionally, while there are quite a few stories that clearly do belong to the science fiction genre as narrowly defined – science-based tales of space opera and alien encounters, glimpses of futures near and far, cosmic adventures and parallel universes – the speculative element could easily be subtracted from some of the science fiction stories with little loss (as with the stories by Alice Sola Kim and Robert Reed). Given what seem to me the more sharply drawn boundaries of the science fiction genre, and the more inclusive character of fantasy as most of us now seem to think of it, all this left me feeling that fantasy predominates in the reading experience.

The volume’s first story, Yoon Ha Lee‘s “Flower, Mercy, Needle, Chain” (first published in the September 2010 issue of Lightspeed Magazine, and previously reviewed here) is a good example of this blurring of boundaries in its presentation of mind-bending, cosmic science fiction in fantasy packaging centering on a timeline-altering superweapon. The plotting is limited, the world-building slender and the characterizations a bit flat – and the story less than perfectly clear on points, so that I am not sure it completely holds together logically – but the strong concept imbues it with a genuine sense of wonder, which along with the briskness of the telling and the grace of the prose, more than carries it.

K.J. Parker‘s “Amor Vincit Omnia” (first published in the Summer 2010 issue of Subterranean Magazine, previously reviewed here), like a great many other recent tales of wizardry, approaches magic as a form of applied science. Here a young practitioner of that science named Framea is required by his superior to stop an adept who may have acquired a theoretically possible, but never before attained, magic of “total defense” making its wielder invulnerable. The problem of defeating an enemy with such a total defense is only the first dilemma Framea faces, his quest plunging him into one difficult situation, one questionable decision after another, with some grave consequences (which are frankly likely to put off some readers). To his credit, Parker does a good job developing his particular concept of magic-as-science, and his writing kept me turning the pages.

Amal El-Mohtar‘s “The Green Book” (which first appeared in the November 2010 issue of Apex, previously reviewed here) tells of Master Leuwin Orrerel’s involvement with the titular occult book, inside of which is a trapped personality. The author’s approach to the story is experimental and frankly oblique, but there is a genuine story beyond the tricks, and genuine emotions, and after a somewhat off-putting opening portion these do come through, so that the tale works quite effectively in the end.

The protagonist of Alice Sola Kim‘s “The Other Graces” (first published in the July 2010 Asimov’s, and reviewed here) is a far cry from the stereotype of the Asian-American girl as the overachieving, privileged, repressed child of parents at once embodying the American dream of immigrant prosperity-through-virtue, and stiflingly traditional in their dominion over a very “proper” household. Quite the contrary, she describes her family (consisting of a mentally ill, homeless father, an older brother who spends his free time staring at paranormal documentaries on the History Channel and spits on the floor, and a worn-out mother holding down three lousy service sector jobs) as “yellow trash,” and Grace is desperate to escape that existence through admission to an Ivy League university. She gets her chance in an intervention by the “other Graces” of the multiverse.

Reading Kim’s story it seemed to me that the science fiction element could easily have been replaced by another unlikely entrée to her desired school, and that this would not have diminished the story’s greatest strengths, which lay in its handling of the quotidian rather than the speculative – the author’s sharp eye for everyday detail, her vivid characters, and her feel for her characters’ social world, from Grace’s status anxieties and class frustrations, to the out-of-control cult of admission to “the good school.”

Geoffrey A. Landis‘ novella “The Sultan of the Clouds” (first published in the September 2010 issue of Asimov’s, and reviewed here) depicts a future where humanity’s expansion through the solar system has become a reality, but on terms that have made the principal beneficiaries twenty exceedingly wealthy and powerful families, like the Nordwald-Gruenbaums. As many a writer has fancied, extremes of corporate and familial wealth have been such as to produce a reversion to pre-modern social and political modes, like what was once called “Oriental despotism,” with Venus a satrapy under the rule of a “Sultan of the Clouds.”

The tale begins when scientist Leah Hamakawa receives an invitation from the Venusian ruler to visit his planet to discuss her research on terraforming. She takes up that invitation, traveling in the company of David Tinkerman, a technician whose relationship with her is (for him) frustratingly ambiguous. Not long after their arrival they find themselves drawn into local intrigues. These turn out to be rather slight in the end, but the world-building – and especially the depiction of the planet’s floating cities – is memorable. And while the science, physical and social, is relatively up to date (extremes of corporate power and a fascination with the trappings of royalty are on the upswing in our time, and Landis’ view of space travel as still ruinously expensive in the future would seem a reflection of our disappointing experiences these past few decades), there is little disputing the retro appeal of a tale drawing inspiration from Edgar Burroughs-style planetary romances and Golden Age space operas and galactic empires. Still, I found myself enjoying this novella as more than just an exercise in nostalgia.

In Christie Yant‘s “The Magician and the Maid and Other Stories” (first published in the anthology The Way of the Wizard) a young woman named Audra spends time with a creepy old man named Miles because he tells her “stories that no one else knew,” and, she hopes, might be able to show her a way back “home,” while in another place and time, a young man named Emil aspires to become a magician. The two storylines, naturally, interweave – quite satisfyingly by the end of Yant’s simple but very charming tale.

Steve Rasnic Tem‘s “A Letter From the Emperor” (first published in the January 2010 Asimov’s, and reviewed here) is set on the fringe of a galactic empire, aboard one of the “messaging and data collection” ships that are the slender connection between imperial authority, and the empire’s outermost settlements. As the story opens Jacob Westman, one-half of the crew of one of these ships, is being questioned about his teammate Anders Nils – whose recent suicide has led to an official inquiry.

Rather than the answer to the interrogators’ questions being the center of the interest, it is Jacob’s inability to think of answers that is crucial, the extraordinary emptiness and loneliness of the lives of these men (Nils, Westman, and the retiring colonel to whom Westman is subsequently expected to convey the titular letter) the heart of the story. The empire they serve does not give an impression of vitality, but more than imperial ascent or decline, what really matters is the faintness with which its presence is felt out on these extreme fringes, where it can seem as if the emperor does not actually exist. Tem’s story conveys this very effectively, as it does the isolation of its characters from each other, in spite of their isolation from everything and everyone else they know during their tours of duty.

Matthew Johnson‘s “Holdfast” (which first appeared in the December 2010 Fantasy Magazine, previously reviewed here) begins with a farmer milking the family cow as dragons fill the sky overhead. Contrary to what one might expect, however, the sight of those dragons does not mark the emergence of Irrel (or for that matter, his son who aspires to be a wizard) as the savior of his realm. Rather this is a slice-of-life, view-from-below story about peasant life in just that kind of enchanted world where the epic hero stuff just happens to “other people.” To Johnson’s credit, it held my interest rather than making me wish he’d written about the battle raging in the distance.

In Charles Yu’s “Standard Loneliness Package” (first published in the November 2010 Lightspeed Magazine, previously reviewed here), it has become possible to transfer feelings and experiences one would prefer not to live through to someone else. This becomes the basis of a business which, as might be expected, outsources the suffering to the cheapest available labor – in this case, the employees of an Indian call center. The resulting tale, which for me had something of the feel of the New Wave about it, focuses on a group of low-level service workers trying to get through another day of life in their particularly brutal corner of the global economy. Their story is rather bleak, but intelligently written and thoroughly engaging.

Rachel Swirsky‘s Nebula-winning novella “The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window” (first published in the Summer 2010 edition of Subterranean Magazine, and reviewed here) is easily the most highly acclaimed of the stories in this volume. Another blend of science fiction with fantasy, it centers on a sorceress in a matriarchal society who is killed but remains as a trapped spirit while history unfolds around her. I didn’t come away convinced that it was the best story of the year, but it certainly impressed me with its sweep and density.

Adam-Troy Castro‘s “Arvies,” (first published in the August 2010 Lightspeed Magazine, previously reviewed here) depicts a world in which humanity is divided into a privileged caste of unborn fetuses, and the “arvies” who exist solely as hosts for the master class who use them for virtual experience, and regard them as totally disposable slaves. Dark, bizarre and brutal, it attracted some widely publicized praise from Harlan Ellison last year (which you can find quoted here).

In Bill Kte’pi‘s “Merrythoughts” (published by Strange Horizons on March 22, 2010) the superhero Typhoon – one of the “Winged Folk,” and regarded as the greatest superhero of his time – returns to his family after a particularly bad fight. The story is less about him than the people left behind, however, the others who cut off their wings and went on to lead workaday lives, which prove to have their own interest in this solid, sensitively drawn piece.

In Samantha Henderson‘s “Red Bride” (published on Strange Horizons on July 5, 2010, and previously reviewed here) a “Var” slave is speaking to the young daughter of her human masters as her fellow slaves rebel around her. She tells the girl of her people’s prophecy about the coming of a messianic leader, about their oppression by humans – and about the mercy she intends to show her young charge. This brief piece (a mere four pages long) is surprisingly twisty, but makes up for any structural defects with the sheer vividness and force of the telling.

Paul Park‘s novella “Ghosts Doing the Orange Dance” (first published in the January-February issue of the 2010 Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and previously reviewed here) is a tangled (and frequently unreliable) personal and familial history going back through the nineteenth century, related by a narrator in a disaster-ravaged near-future United States. The points “Ghosts” makes about the way we make memory and narrative from the mess of life are old points by now, done to death after a century of Modernist experimentation, some disjointedness in such a story is all but unavoidable, and I’m not sure that I’m satisfied with the way in which it added up – but as is the case in the best such writing, the bits were engaging enough to keep me reading on even when I wasn’t sure what to make of it.

I reviewed Gene Wolfe‘s “Bloodsport” last year, when it first appeared in Swords & Dark Magic. On rereading it, I came away with the same impression I had then: Wolfe’s talents for generating ambience and producing impressive prose are on display here, but so is his tendency to the kind of self-indulgence that, alas, highbrow critics fall for far too easily.

In Carol Emshwiller‘s “No Time Like the Present,” (first published in the July 2010 Lightspeed Magazine, and previously reviewed here) a young girl makes friends with a member of a community of new arrivals in her small town who buy up the best houses, keep to themselves – and seem to possess quite a bit of science fiction-type technology, like the “education boxes” which provide the user with an experience of virtual reality. Emshwiller does very little with this premise, however, in a story that seems deliberately (and perhaps pointlessly) ambiguous on every level, from the time in which the story is set to what happens at the conclusion of the narrative, and while I never found reading it a trying experience, it left little impression.

C.S.E. Cooney‘s “Braiding the Ghosts” (first published in Clockwork Phoenix 3, and previously reviewed here) tells the story of Nin, a young girl who, after the death of her mother, grows up in the care of her grandmother Reshka, an old, powerful sorceress who enslaves ghosts as domestic servants in her lonely home. She raises Nin to do the same, but her relationship with the ghosts becomes quite a different thing from Reshka’s – and those differences bring their long-running conflict to a climax. This does not disappoint, Cooney developing quite a compelling tale out of this premise.

In Neil Gaiman‘s “The Thing About Cassandra” (which first appeared in the anthology Songs of Love and Death) a thirtysomething artist is surprised to find that the made-up girlfriend he told people about as an adolescent has turned up in his life, apparently a real human being. There’s a twist, of course, one I found predictable and rather slight, but the story entertained me all the same.

Willow Fagan‘s “The Interior of Mister Bumblethorn’s Coat” (first published in the October 2010 Fantasy Magazine, and previously reviewed here) is the story of a weary man leading a new life in the strange new locale of Fleet City. However, he carries the world he left behind with him at all times, in a way that is not strictly metaphorical. Essentially, an exploration of Bumblethorn’s situation, the imaginative richness and vivid detailing of the course his life has taken, and the place where he now finds himself (unmatched in this volume for sheer trippiness) – and what is more, Bumblethorn’s humanity – combine to make it memorable.

Peter Watts‘ “The Things” (which first appeared in the January issue of Clarkesworld Magazine, and the most acclaimed piece in the whole volume other than Swirsky’s) is a retelling of genre legend John W. Campbell’s classic “Who Goes There?” – his novella about an expedition in Antarctica which encounters a predatory, shape-shifting alien who may be any one of them, which has twice been filmed by Howard Hawks as The Thing From Another World (1951), and John Carpenter as The Thing (1982) (to which Watts’ title alludes). The twist here is that the story is told from the point of view of the alien.

I have to admit that the trope of a small group of people stuck at an isolated site and forced to figure out which of them is a killer has never been a favorite of mine, in either its speculative or mundane forms. Still, Watts’ well-executed variation on the story lends a new interest to the well-worn routine, and should stand up well even for a reader unable to appreciate it as homage or in-joke.

Paul M. Berger‘s “Stereogram of the Gray Fort, In The Days of Her Glory” (from the June 2010 Fantasy Magazine) is a vignette set in an age in which humanity has long since been conquered by elves. Here a mixed human-elf couple – Jessica and Loran – take a tour of the ruins of the fortress that was the last action of the human-elf war, during which they are invited to see a “stereogram” of the site, which enables visiting couples to see the fort as it appeared at the moment of its famous last stand. Given their differing heritage, it is no surprise that they come away with quite different experiences in this entertaining allegory about the different meanings the same historical event often has across cultural lines.

Alexandra Duncan‘s “Amor Fugit” (first published in the March-April 2010 Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and previously reviewed here), like Yant’s “The Magician, The Maid, and Other Stories,” intertwines two stories – in this case, of lovers separated by time (in quite different ways), with the inspiration coming from Classical myth rather than fairy tales. The results similarly charm (though in this case, the tale also has a bittersweet note).

Robert Reed‘s “Dead Man’s Run” (first published in the November-December 2010 Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and previously reviewed here) is a who-dun-it set in a running club. The speculative twist is that the murder victim has a back-up avatar of himself which has enlisted the protagonist, a member of the club, to investigate his death. The essential premise of a running club murder mystery did not particularly intrigue me, and in the end I never found myself drawn in the way I hoped I would be despite that. It also seemed the case that this novella – the longest in the anthology at sixty pages – was much longer than it needed to be. As was the case with Kim’s story, it also seemed to me that the handful of speculative touches (including the central gimmick) could easily have been dispensed with while leaving the narrative virtually intact, though unfortunately this story’s treatment of its “mundane” elements proved rather less interesting.

In Charlie Jane Anders‘ “The Fermi Paradox is Our Business Model” (which first appeared on Tor.com in August 2010, and was previously reviewed here) a party of extraterrestrials fly to Earth to check on the planet’s condition, and find a post-apocalyptic wasteland – but not a completely lifeless one, as a few million survivors reside in a high-tech megastructure in Australia. Humanity’s first contact with aliens who regard it as set on a self-destructive course is a fairly old trope by now (take, for instance, the 1951 classic The Day the Earth Stood Still), but Anders’ adroitly (and jokily) puts it to use as a story at once about “intelligent design” (in this case, a kind quite different from what American proponents of the theory generally believe), slash-and-burn capitalism at its most extreme, and one possible answer as to why, in a galaxy presumably full of intelligent life, the extraterrestrials have not made their presence known to humanity.

In Matthew David Surridge‘s “The Word of Azrael” (which first appeared in the Winter issue of Black Gate magazine, an excerpt of which can be read on the magazine’s web site), warrior Isrohim Vey encounters the Angel of Death on the battlefield. Having seen the Angel’s smile once, he spends the rest of his life pursuing another glimpse of it – a colorful, wide-ranging, action- and adventure-filled epic journey in the tradition of Conan the Cimmerian and Elric of Melnibone. The resulting piece is one of the strongest heroic fantasies I have seen in years.

In Damien Broderick‘s “Under the Moons of Venus” (first published in the Spring 2010 issue of Subterranean Magazine), the protagonist Blackett deals with the emotional, epistemological, ontological and cosmological problems raised by the disappearance of most of the rest of humanity as he lives among a handful of other “left behind.” He is convinced that they have been transported to a Venus somehow made habitable, and that he was briefly there himself but somehow dragged back to Earth. This has left him desperate to “get back” to what he thinks is humanity’s new home.

I found the story engaging, but also deeply disorienting – as much because of the telling as the subject matter. Full as it is of unexplained and inexplicable details, while being nearly devoid of the answers to the questions bound to crop up in the mind of many a reader, it struck me as an exercise in surrealism (or postmodern incoherence) rather than the scientific extrapolation I had expected from the premise. (Indeed, in his own review of this anthology, Brit Mandelo describes this story as “almost equally SF and fantasy”).

In An Omowoyela‘s “Abandonware,” (first published in the June 2010 issue of Fantasy Magazine) an adolescent named David is dealing with the recent death of his older sister Andrea – all by himself, as her death has reduced his family to just David and his father, who are mutually clueless about each other. While rummaging in Andrea’s old computer equipment (which includes zip disks, the “abandonware” of the title), he encounters a mysterious program that makes him feel as if he is still connected to her. Though there were a few notes that didn’t quite ring true, on the whole Omowoyela’s treatment of the relationships among her characters – what the story is really about – are quite effective.

The anthology’s last piece, Elizabeth Hand‘s “The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s Bellerophon” (which first appeared in the anthology Stories) depicts the obsession of museum security guard Robbie and his friends with a pre-Wright Brothers flying machine, which ultimately drives them to recreate its flight. The speculative element (whether one labels it science fiction or fantasy) is slight, but as in the stories by Kim and Gaiman, Hand’s handling of the everyday details that comprise the novella’s bulk is more than enough to make it engaging.

It is noteworthy that despite the steampunk boom of recent years, Hand’s story is the only one in the volume to make any significant use of retro-futuristic technology. However, if the retro-futuristic is absent, so is much of what we have recently taken for plain old futuristic, the splashy Singularitarianism so fashionable just a few years ago virtually absent (the slight touch of the transhuman in Reed’s story aside), along with the high-tech grit of cyberpunk and post-cyberpunk, while hard-edged extrapolative writing is generally scarce here. Just as in the 1970s, another period of economic stagnation, dashed expectations and declinist anxiety, a softer kind of science fiction, less concerned with new technology and realistic futures, prevails, and much of what science fiction is present here is often backward-looking and self-referential (as in Watts’ “The Things”).

Interestingly, the fantasy stories seem to parallel this change. The “traditional” (e.g. quasi-Medieval) fantasy so often derided in recent years (as in these recent remarks by John Clute) is very prominent here, as in the tales by Parker and Johnson. Meanwhile the contemporary, urban fantasy that is conversely celebrated as the scene of the genre’s most vibrant writing (see Clute again), and which certainly seemed present in abundance in round-ups of the year’s best not long ago (as in the 2009 edition of Strahan’s anthology series), is much less conspicuous here – perhaps a reflection of the same desire to fly the modern world and its troubles, and a future that as of 2011 seems less promising than before, even when compared with the deflated expectations of the early twenty-first century.