"An Incident at Agate Beach" by Marly Youmans

"Among the Tombs" by Reggie Oliver

"American Morons" by Glen Hirshberg

"Shallaballah" by Mark Samuels

"Shallaballah" by Mark Samuels"Denial" by Bruce Sterling

"Northwest Passage" by Barbara Roden

"Kronia" by Elizabeth Hand

"Where Angels Come In" by Adam L.C. Neville

"The Souls of Drowning Mountain" by Jack Cady

"The Last One" by Robert Coover

"The Ball Room" by China Miéville, Emma Bircham, & Max Schäfer

"Vacation" by Daniel Wallace

"Ding-Dong-Bell" by Jay Russell

"A Case Study of Emergency Room Procedure and Risk Management by Hospital Staff Members in the Urban Facility" by Stacey Richter

"Boman" by Pentti Holappa

"The Machine of a Religious Man" by Ralph Robert Moore

"Hot Potting" by Chuck Palahniuk

"My Father’s Mask" by Joe Hill

"The Guggenheim Lovers" by Isabel Allende

"The Pavement Artist" by Dave Hutchinson

It’s a short piece, but anything longer wouldn’t have worked as well. And even though there are a lot of films and short stories playing upon the American tourist being tortured in Europe motif (Turistas, Hostel, etc.), "American Morons" works so well because of how oblivious the main characters are to their surroundings.

"Shallaballah" by Mark Samuels is an intense examination of the lengths one will go through for the allures of fame and the people that will take advantage of these fame-seekers just for the hell of it. That’s the premise behind Samuel’s fantastic morality play, and he milks it for every ounce of terror and creepiness possible.

Sogol’s once beautiful and famous face has been mangled and scarred. He knows, and we know, his Hollywood career is over. Desperate to get back in the business, Sogol hires the services of the enigmatic Mr. Punch. He’s told to arrive at a deserted building, where his body becomes the possession of Mr. Punch. What atrocities will the reader discover with Sogol? What are these bizarre narrative interludes? To give away anything would be a disservice to the tight thriller Samuels has created. This is a must read for any fan of horror and definitely marks Mark Samuel as someone to watch. (Reviewed by Jason Sizemore.)

Bruce Sterling’s "Denial" is a fable set in a Balkan-like nation, a mixing-board for the world’s major religions. Since it’s a fable by Bruce Sterling, expect no homilies or consolation. A village is flooded, and the protagonist spends the story trying to convince his wife that she drowned. But the drowned wife is so much more agreeable than the version he knew… Sterling, as usual, is incisive and funny, with a twist I should have seen coming but didn’t. Like his sf and nonfiction, this story bristles with interest in practical matters: it really is a big deal to lose your toolkit in a country where you can’t replace them at Home Depot. (Reviewed by Thomas Marcinko.)

Barbara Roden’s “Northwest Passage” takes places in backwoods British Columbia in a cabin where sixty-three-year-old widow, Peggy, lives during the summer. One day, two young men, Jack and Robert, camping a mile or so away, introduce themselves. Jack is a friendly enough fellow, but Robert is moody and brusque. Then Jack goes missing, and Robert is beside himself with worry. Roden does know how to amp up the suspense, but this story was a little short on ideas for my taste. Jack moves through the story talking about the hills having eyes and mentioning the movie by that name, but the MacGuffin here is pretty vague. Also, at 13,000 words, I thought it way too long. The exposition about Peggy’s dead husband was unnecessary, and the dialogue with the boys could’ve been trimmed. I’m sure some readers like tales where the setup and suspense are dragged out, but I felt manipulated. A skillfully told tale, but in the end, it arrived nowhere important. (Reviewed by Marshall Payne.)

"Kronia" is from the always interesting Elizabeth Hand. Here, she writes a short story presented in a similarly disjointed narrative manner as the groundbreaking and cult short film, La Jetée. Hand describes a series of brief encounters, longer meetings, and potential (or did they really happen?) what-ifs between a man and a woman. It’s a nice story to cultivate thoughts about predestination, reality, and, of course, love. A recommended read. (Reviewed by Jason Sizemore.)

Elizabeth Bear‘s short story, "Follow Me Light," is a beautiful, haunting, modern-day fairy tale. Isaac Gilman, Pinky to all, is a talented lawyer, but horribly crippled and hideous. He has a mysterious past, and an aura which glitters with "electric blue fireflies." Maria Delprado is the lawyer and psychic who loves him, who sees the beauty and the pain in him, and becomes embroiled in a story as old as the sea. Pinky introduces her to a world of primeval mythology, a brother’s feud, and the value and power of love.

Adam L. G. Nevill tells a haunted house story in “Where Angels Come in.” Lying in his convalescence bed, a young boy whose body is numb on one side tells of how he became that way. A few months back, he and his young friend, Pickering, climbed the wall and entered the mysterious white house on the hill. When things (children, pets, etc.) turn up missing in the town, this is the likeliest place they go. Nevill is an experienced horror writer of credible talent, but I found myself skimming to get to the end. I won’t describe the horrible things he piles up, one on top of the other, once the boys are in the house. Nevill wrote this as an homage to British ghost story writer M. R. James (1882-1936). If you enjoy these sorts of tales, check it out. (Reviewed by Marshall Payne.)

At first, I didn’t know what to make of "Twilight States" by Albert E. Cowdrey. I was entertained, the story is certainly well written, but I’m not sure I enjoyed it.

The protagonist, Milton, is the owner of Sun and Moon Metaphysical Books. He has a complicated past that is tied up with a story in a rare issue of a World War II fantasy magazine. When Erasmus Bloch, who happens to be Milton’s deceased older brother’s ex-psychiatrist, comes looking for that very magazine, Milton’s careful equilibrium is destroyed.

The story-within-a-story is effectively handled, leaving the reader with an unnerving sense of foreboding. Milton, as a narrator, shifts from being unreliable to reliable, making it difficult to get a fix on his motivations, but Cowdrey pulls it off. I was really won over, and the fact that I didn’t like it at first made me like it all the more at the end. (Reviewed by Aimee Poynter.)

1. Heroism consists of action

2. Do not act until necessary

3. You will know that the action is right if everything happens swiftly

4. Do whatever is necessary

5. Heroism is revealed not by victory but by defeat

6. You will have to lie to others, but never lie to yourself

7. Organized retreat is a form of advance

8. Become evil to do good

9. Then do good to earn merit and undo harm

"Yet he takes no action.”

"The Neighbors make the magic of war.”

Jack Cady constructs a fascinating account of Appalachia Kentucky in the 1950s in "The Souls of Drowning Mountain." It was around the period of time when the Federal Government thought it was time the "hillbillies" caught up with the rest of the Western world. The attention to detail Cady gives to the people of the times and the community’s culture are remarkable and right on the money (as this reviewer is from the same town "The Souls of Drowning Mountain" is set). In fact, the historical accuracy delivered more impact to me than the actual story, a set piece about a group of ghosts/zombies back to torment their tormentors. (Reviewed by Jason Sizemore.)

According to the small blurb by Kelly Link and Gavin Grant which precedes this story, "The Last One" by Robert Coover is a "joyful reworking of Bluebeard." I wouldn’t call this a joyful story. It’s another dark morality tale if anything else, but it was a joy to read.

We’re introduced to a rather arrogant nobleman and his obedient, loving bride. They make love. They play lovers’ games. Many words are dedicated to showing the joys of their relationship. Then things take a dark turn as we discover the nobleman has a "blue" room that is forbidden to all but him. All his other brides are dead by his own blade due to their curiosity. But this new bride, she doesn’t care for the blue room. She only wants to play in her nursery. As time goes on, the nobleman becomes obsessed by what type of games the bride is playing. Is she cheating on him? Or perhaps engaging in some other manner of unseemly conduct? The tables are turned. Coover shows a skilled hand pulling off an O. Henry style ending that would have been mismanaged by a lesser skilled writer. (Reviewed by Jason Sizemore.)

"The Ball Room," co-written by China Miéville, Emma Bircham, & Max Schäfer, takes the concept of a classic English ghost story and places it in the milieu of a children’s playpen, where all those tiny, plastic balls are set to cushion a youngster’s fall. The story does build tension well and leaves some haunting images, but in the end, it failed on the whole as a ghost story. Mostly because Miéville can’t help but thrust in a socialist comment on capitalism, but also because the story itself brought nothing really new or interesting to the genre.

As an English ghost story, it doesn’t make any comments on the genre as a whole, nor does it scare too well. As I said, some images stand out and some parts are fairly creepy, but as a whole, it is the least interesting of all the horror stories accepted for this anthology. A good classic tale when there is nothing else to read, but nothing to get worked up over. And definitely not anything frightening enough to keep you up at night. (Reviewed by Paul Jessup).

Daniel Wallace tells a tale of paranoia in “Vacation.” Told in the second person, you arrive in Aristea for a vacation, eventually lose your luggage, and are lured to a building by your cabdriver, whereupon things get even worse. Throughout, you are convinced that your best friend, back in the States, is sleeping with your wife and that everyone knows about it and is laughing behind your back. I usually don’t have a problem with second-person narratives, but its use in this story greatly annoyed. I’m sure that’s what the author meant to do, to make the reader uncomfortable. Perhaps other readers enjoy this sort of reading experience. I don’t and felt manipulated from the opening “you.” (Reviewed by Marshall Payne.)

Jay Russell serves up a gory bloodfest in “Ding-Dong-Bell.” Johnny, called the Boy Detective, follows his older brother, George, and his friend, Lenny, to a house where he witnesses a horrible occurrence through the window. The two older boys have tied Lenny’s Aunt Clara to a bed and are doing more appalling things to her than rape. Of course, the Boy Detective is caught, brought inside, and forced to fornicate with the aunt so he’ll feel guilty and keep his mouth shut. Then they mutilate the woman and, “Ding-Dong-Bell,” toss her down a well. Ashamed, the Boy Detective grows up to be the Director of the FBI and hunts George and Lenny, who have become notorious serial killers. And everyone knows that the FBI always gets their man. I’m ambivalent about this one. On one hand, Russell’s depiction of gore and wickedness does show how depraved the human mind can become, but on the other, I’m wondering if this was all really necessary. I wasn’t offended by it, though; I was bored. I know horror is a broad field, but this tale had no supernatural element, so I wouldn’t call it speculative fiction. It’s a crime story and out of place in this anthology. But if gratuitous sex and violence are your thing, this will probably ring your bell. (Reviewed by Marshall Payne.)

Stacey Richter delivers a funny, if a bit forgettable, bit of experimental fiction in her story "A Case Study of Emergency Room Procedure and Risk Management by Hospital Staff Members in the Urban Facility." A woman akin to a fairy princess enters an urban emergency room. She’s injured and requires an extended stay to heal. During this time, the staff all become drawn to the mysterious woman and discovers that she might be the victim of spouse abuse. When her evil prince comes to take his quarry, the hospital staff decides to make a stand for the princess. Engaging and charming, the story delivers the entertainment, but it goes down predictable pathways and probably would have been better if not presented in the "report" style. (Reviewed by Jason Sizemore.)

"The Scribble Mind" by Jeffrey Ford is the story of a woman obsessed with a pattern and its implications. Pat is a graduate student studying art. He is just settling in for the semester when he runs into Esme, a girl he knew in high school. She, too, is an art grad student. And, as they know each other, it’s natural that they start seeing each other for breakfast and such—spending time with someone they know to wind down from the week.

Pat discovers a painting that is to be displayed in an upcoming show at the school. Esme knows the painting. It’s a scribble that seems to be a constant, reproducable by people who can remember being in the womb. Esme becomes obsessed with this scribble and the memory that is associated with it.

Esme hatches a plan to get the scribble artist to reveal to her his memory. Unfortunately, the artist is a fake with his own agenda regarding those who can “remember.”

“The Scribble Mind” is a story of obsessions; Esme’s obsession with those who can “remember,” and Pat’s obsession with Esme. The story was most accessible to me through Pat’s obsession, as I can envision having such an obsession myself. And it works very well, given that we mostly see Esme’s obsession through Pat’s eyes. Mr. Ford’s story is a compelling read. (Reviewed by Michael Fay.)

“Boman” is by Finnish writer Pentti Holappa. Translated from his native Finnish, its narrator tells the tale of his talking dog, Boman. The narrator is an educated man and before he learns that his dog can talk, she (the dog) has a bad habit of eating his books. Much of the story concerns Boman’s adventures, and the narrator telling the reader what the dog told him. The story meanders, but I found it poignant and well written. Much is made of growing wings in this tale, and toward the end, Boman does. While obviously a metaphor, I found the wings to be an incongruous image that didn’t quite work. And no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get past the fact that I was reading a story about a talking dog. (Reviewed by Marshall Payne.)

“The Machine of a Religious Man” by Ralph Robert Moore is a difficult tale to synopsize. Told from an odd point of view, this works better than most second-person stories because the “you” of the narrative takes a back seat and mostly watches the action unfold. The reader accompanies a fellow named Bonay as he invades a rich Indian chief’s home to demand his help. Bonay’s boss, a rancher named Gordon, is in the car outside crying. Gordon’s wife, daughter, and granddaughter are all dead—the wife a few years ago, the daughter last year, the granddaughter that day. The granddaughter is trapped underneath a pond that has frozen over, and he wants the chief to have his cattle stampede the frozen pond so the ice can be broken and his granddaughter’s body can be retrieved. This was written well, gripping, and with a colorful cast of characters, but I found the premise absurd. Yes, the rancher does have a purpose to all this in the end, but I still found it farfetched. And mental aberration doesn’t qualify to make this speculative fiction. A brilliantly realized failure. (Reviewed by Marshall Payne.)

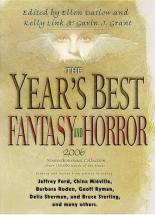

Generally, there’s not much gore in each year’s edition of The Year’s Best Fantasy & Horror. But it appears that editor Ellen Datlow has a soft spot in her heart for one of the most effective gore writers in the business, Chuck Palahniuk. "Hot Potting" is a nasty little work about a woman and her bed & breakfast inn that is next to some hot springs. People fall in the springs. Nastiness ensues. Probably not for those readers with a sensitive stomach, but overall an effective piece. (Reviewed by Jason Sizemore.)

Joe Hill‘s "My Father’s Mask" is a complicated story that could be seen both as allegory and as abstract surrealism. Under the depth of symbolism, one gets a stark feeling of loss and loneliness that most writers can’t even come close to achieving in entire novels, let alone in the space of a short story.

Isabel Allende writes a dreamy story about love and a museum in "The Guggenheim Lovers." In short, a young couple are caught making love in the Guggenheim. How did they get in? Why didn’t the alarms ring? Hey, how come they’re not showing up on the video surveillance? We follow the short investigation of a local detective as he eventually comes to the conclusion that the reader knew all along. An entertaining read. (Reviewed by Jason Sizemore.)

I’m not quite sure what it is about Theodora Goss’s writing that I like so much, but every time I read one of her stories, I am drawn in. "A Statement in the Case" is no exception. It is told as a statement to a police officer by a local guy, named Mike, after a fire decimates the corner pharmacy. The pharmacy is owned by Istvan Horvath, a Hungarian immigrant who is a friend of Mike’s.

Istvan’s wife is a younger woman who cared for Istvan’s mother in Hungary. Istvan brings her to the United States after his mother dies. Their relationship is uncomfortable and Goss illustrates their differing philosophies of life in the New World effectively. The ending is beautiful and a little horrific. The focus on the Horvath’s relationship made the revelation at the end all the more chilling. And the end is truly disturbing in a way that questions our carefully structured reality. I really enjoyed this one. (Reviewed by Aimee Poynter.)

Although “The Pavement Artist” by Dave Hutchinson is a horror selection in this anthology, it has a science fictional premise. Thomas is a gallery owner in the day-after-tomorrow London art world. Twenty years ago, the Japanese invented a method for recording human personalities, a process known as “cracking.” For convicted murders, death row has become The Distillery where personalities are saved and the human body put to death. Enter the modern artist Coypu, who creates bizarre sculptures with moving arms and accompanying holograms, each downloaded with a human personality. Soon Coypu is murdered, and the end is the revelation of where his personality went. I wasn’t surprised by the ending, but was glad that the technology figured into the denouement instead of this turning out to be another whodunit. I wouldn’t call this fantasy or horror, more of a cyberpunk tale in the snobbish art world: a Gibsonesque Warholian crime drama. Enjoyable. (Reviewed by Marshall Payne.)