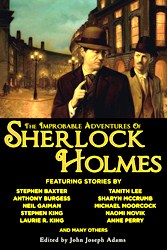

The Improbable Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

The Improbable Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

Edited by John Joseph Adams

(Night Shade Books, Sept. 2009)

“The Doctor’s Case” by Stephen King

“The Horror of the Many Faces” by Tim Lebbon

“The Case of the Bloodless Sock” by Anne Perry

“The Adventure of the Other Detective” by Bradley H. Sinor

“A Scandal in Montreal” by Edward Hoch

“The Adventure of the Field Theorems” by Vonda N. McIntyre

“The Adventure of the Death-Fetch” by Darrell Schweitzer

“The Shocking Affair of the Dutch Steamship Friesland” by Mary Robinette Kowal

“The Adventure of the Mummy’s Curse” by H. Paul Jeffers

“The Things That Shall Come Upon Them” by Barbara Roden

“Murder to Music” by Anthony Burgess

“The Adventure of the Inertial Adjustor” by Stephen Baxter

“Mrs Hudson’s Case” by Laurie R. King

“The Singular Habits of Wasps” by Geoffrey Landis

“The Affair of the Forty-Sixth Birthday” by Amy Myers

“The Specter of Tullyfane Abbey” by Peter Tremayne

“The Vale of the White Horse” by Sharyn McCrumb

“The Adventure of the Dorset Street Lodger” by Michael Moorcock

“The Adventure of the Lost World” by Dominic Green

“The Adventure of the Antiquarian’s Niece” by Barbara Hambly

“Dynamics of a Hanging” by Tony Pi

“Merridew of Abominable Memory” by Chris Roberson

“Commonplaces” by Naomi Novik

“The Adventure of the Pirates of Devil’s Cape” by Rob Rogers

“The Adventure of the Green Skull” by Mark Valentine

“The Human Mystery ” by Tanith Lee

“A Study in Emerald” by Neil Gaiman

“You See But You Do Not Observe” by Robert J. Sawyer

Reviewed by Steve Fahnestalk

Although my mandate is to review new stories rather than reprints, ye olde editor doesn’t quibble at my selecting a few choice baubles from a collection such as this, even if they’ve seen print before. As it is, the only truly new story in the book is “The Adventure of the Pirates of Devil’s Cape” by Rob Rogers, which I will certainly review here.

Arthur Conan Doyle died in 1930, almost 80 years ago, yet his creation, the world’s first and only “consulting detective,” Sherlock Holmes, is still alive and being carried on by all sorts of writers. Whether you consider these stories homages, imitations, or mere pastiches, it’s undeniable that for most readers, the phrase “Quick, Watson, the game’s afoot!” sends a short frisson of excitement up the spine. In fact, Adrian Conan Doyle, the original author’s youngest son, also wrote a number of Sherlock Holmes stories (some with the “assistance” of John Dickson Carr) in the 1950s. The admirers of the Holmes stories must number in the millions; in fact, some extremely enthusiastic fans have formed chapters of the “Baker Street Irregulars”—a fan club named after the “street Arabs” (urchins) that Holmes used as errand boys and messengers—all over the world.

What’s the attraction for modern readers of a detective working in an increasingly distant Victorian era? Why should there be not one, but two current movies (one American, one British) on the Great Detective who, truth be told, would probably be totally baffled by today’s forensic science (although, on the face of it, he [or at least Dr. Joseph Bell, the original model for Holmes] was one of the originators of that science)? And could one really write (at least in Victorian times) a monograph on “140 different types of cigar-ash”? I can’t answer the latter, but I could tell you that for me, part of it is viewing that lost Victorian era from a street-level perspective, seeing the streets and alleyways not from a Mary Poppins upper-class nanny viewpoint, but from the dirty, coal-fog-laden, muffler-wearing Springheel Jack or Sweeney Todd commonplace view.

Many think of Holmes as a thin, ascetic, cocaine-using, violin-playing intellectual (possibly influenced by Basil Rathbone or Jeremy Brett’s portrayals), but in fact though he was thin, he was athletic, extremely strong, a skilled boxer, fencer and singlestick player, master of the Japanese martial art known as “baritsu” (an invention of Doyle’s), and liked nothing better than getting down and dirty in pursuit of criminals–like Robert Downey, Jr., in the aforementioned American movie. (And, parenthetically, for those who cite a “homoerotic undertone” in that film, at least one fan says that “There is as much canonical evidence that Holmes was gay as there is that he was Mr Spock’s ancestor.”)

Did I say “canon”? Yes, in fact—like religious people, the Holmes enthusiasts can cite scripture—the original writings of Doyle are canon, while those writings not Doyle are said to be apocrypha. But there is apocrypha and there is unacceptable apocrypha, at least in my opinion. Which brings us to the book, which is touted as “The Improbable Adventures of…”—and in several cases, there are fantasy or science-fictional aspects to these stories. (I may point out, however, that however much Doyle believed in “fairies at the bottom of [his] garden,” Sherlock Holmes was an ardent rationalist and materialist and believed in nothing supernatural. And no canonical cases, indeed, had other than materialistic solutions.

Although the “The Doctor’s Case” by Stephen King is competently written, it violates canon in one extremely important way—King makes the Great Man allergic to cats as a plot point. Now I’m not implying that 19th century London is overrun (like Rome) with wild moggies, but the fact remains that there are enough cats around that Doyle himself would have mentioned such an allergy, and it would probably have hampered Holmes in his disguises, of which he had many. For that reason, the story of a true “locked-room” murder gets a fail in my book. The solution was ingenious, but you don’t mess with canon.

Another epic fail is Laurie R. King’s “Mrs Hudson’s Case”—in which Holmes does not solve the mystery (although his housekeeper, Mrs. Hudson does)—and which King uses her own detective, featured in her own books, as the narrator. Talk about self-serving. Where did it say this book is the improbable adventures of Mrs. Hudson? For crying out loud, in a Holmes book, have Holmes stories! And I dislike the way she says Holmes is “dismissive” of women and, indeed, has him talking very rudely to Mrs. Hudson—something he would not do, in my opinion.

Another attraction for modern writers of Holmes stories is turning canon on its ear by making Moriarty the hero and Holmes the villain (perfectly acceptable in a Holmes book, in my opinion), or bringing in real people or fictional characters and settings from other writers, such as M.R. James. Karswell, the real magician from his “Casting The Runes” appears in Barbara Roden’s “The Things That Shall Come Upon Them”—or at least his dwelling does. You may recall that Karswell (both in the story and in the terrible movie based on that story—Night of the Demon with Dana Andrews [remember from Rocky Horror Picture Show—“Dana Andrews said prunes/gave him the runes/and passing them used lots of skills”]) used to dispose of his enemies by passing them rune-inscribed slips of paper that summoned a murderous demon.

Another fictional character used in “The Adventure of the Antiquarian’s Niece” by Barbara Hambly is William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki (“The Ghost Finder”) and his “electric pentacle.” The eras are roughly the same (I can’t recall if Carnacki was actually Victorian or a little later) and the story involves some of Lovecraft’s Old Ones as well, namely Yog-Sothoth. In this case, it’s okay to have a supernatural solution, because Carnacki (for some reason Hambly misspells it as “Carnaki”) fends off the “eldritch horrors” with science. A fun story (for someone with my twisted sense of humor) about stealing and possessing bodies.

Other notables brought into the Holmes apocrypha by these (mostly) superbly talented writers include Bram Stoker and H.G. Wells; other characters include Doyle’s own Professor Challenger in what I consider to be a very silly story involving dinosaurs: “The Adventure of the Lost World” by Dominic Green, in which a megalosaurus hatched from an egg from Challenger’s ill-fated expedition is trained to attack its victims by using a trombone, which sounds like a hadrosaur’s call and sparks a murderous rage from said beast.

Another, better tale is “The Vale of the White Horse” by Sharyn McCrumb, in which both Holmes and Watson appear as principals (which they don’t in the Laurie King story), but the actual solution to the crimes being committed is provided by McCrumb’s own wise woman, Grisel Rountree of Dorsetshire. A nicely told tale which involves the famed “white horse” of the chalk hills.

One of my favorite stories (besides the Hambly) was Neil Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald”—which presupposes a world in which Lovecraft’s Old Ones actually took over the world… but most else is the same, except that they (the Old Ones) take the odd human sacrifice—oh, yes, and the Queen and her consort are not what we’re used to—in fact, she’s not actually a human being—though she can recognize quality when she sees it. Watson’s war wound, which in our world was caused by a “Jezail bullet” is, in their world, a sucker wound from some loathsome beast from a subterranean Afghan lake. This story is a complete black humor romp that nonetheless manages to adhere to canon quite well, I feel.

Not quite so the only original story in this anthology—“The Adventure of the Pirates of Devil’s Cape” by Rob Rogers, which puts Holmes and Watson in Rogers’ own invented locale, Devil’s Cape in Louisiana. Yes, Holmes and his faithful chronicler travel to the States to meet with Inspector LeStrade’s cousin, who is an officer of the New Orleans Police, and from there to the notorious pirates’ hangout, Devil’s Cape. There they meet the mysterious O Jacaré, who has kidnapped some ex-circus performers who became rich in the Gold Rush of California and retired from their “freak show” careers. The story is well told, but the supernatural element, which earned my disapprobation, is never explained rationally, which does not fit with canon. However, the story is well enough told to be considered good.

There are twenty-eight stories in all, by such writers as Michael Moorcock, Vonda McIntyre, Peter Tremayne, Anne Perry, and most of them are good. A few are excellent—and I’ve not pointed all of them out to you here, as they have all (save the Rob Rogers story) seen publication elsewhere—so for your $15.95 you get one whale of a trade paperback. If you’re a Holmes fan, or even if you’ve never read a Sherlock Holmes story, you can’t do a lot better than this for value. Who knows, when you’re done reading these tales, you just might want to try a spot of pastiche yourself.