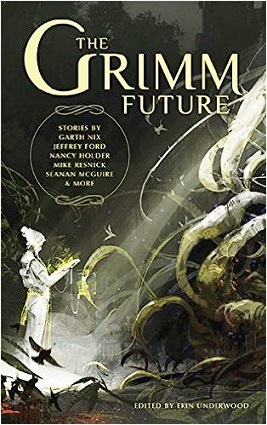

edited by

Erin Underwood

(NESFA Press, Feb. 2016, hc, 276 pp.)

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

In The Grimm Future, Erin Underwood presents fourteen new short stories inspired by Grimm fairy tales, set in the dark future. In a typical short-story compilation, a reader is fortunate to find a quarter or a third of the stories really merit recommendation. The Grimm Future offers a much brighter outlook, inverting the numbers: over three-quarters of its original stories are winners. As short-story compilations go, this is a “don’t walk, run” situation. If you like fairy tales, this alone should be enough to decide The Grimm Future deserves a place on your bookshelf.

Yet … there’s more. In addition to fourteen new stories, editor Erin Underwood provides some perspective: following each new story is an English version of the original Grimm inspiration, based on Margaret Hunt’s 1884 translations. Since many Grimm Future tales are inspired by lesser-known tales, the odds are good many readers will discover the originals are as new to them as the retellings. Students of story design will enjoy comparing the originals to the retellings. Although “Hansel and Gretel” depicts children overcoming obstacles through cleverness – the preferred modern solution, in which the protagonist engineers her own deliverance – Grimm originals frequently depicted virtuous innocents who, through no ingenuity of their own, have their problems resolved for them by supernatural forces – seemingly, based on moral merit. “Cinderella” may lead this pack, but “The Star-Talers” and “The Juniper Tree” deliver the same kind of divine justice that’s hard to sell to modern readers raised on a cause-and-effect world repeatedly revealed in the global news as not predominantly governed by the principle of justice – divine or otherwise. The moral that virtue will attract divine deliverance, and vice will induce nature itself to deliver a suitable comeuppance, is not the moral of the dark future. The Grimm Future’s authors aim the moral of their retellings not at an audience of old but at the dismal future – a fact that, to the modern reader, is generally for the better.

Garth Nix’ “Pair of Ugly Stepsisters, Three of a Kind” opens on a pair of underpaid maintenance workers required to support trillionaires’ planetoid-sized pleasure yachts after an AI scare strands all their occupants behind individualized automated quarantine blockades that isolate each in its own orbit. The job they land at the open of “Three Of A Kind” takes them to Grimm World, a worldlet filled for the amusement of its owners with an AI-controlled supporting cast to make a fairytale hero of the one in command in any of the fairytales the ship was designed to support. Our dark-future scullery maids act with an unexpected but delightfully unsentimental disregard for the worldlet’s fairytale cast. For color, Nix provides elements of “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Rapunzel,” “The Ugly Sisters,” and “Little Brother and Little Sister”; however, the story does not depend on these stories or an understanding of them to follow and enjoy. It’s easy to enjoy the protagonists, both self-sufficient badass operators fully capable of scratching anybody’s itch for competence porn, as they work in dangerous conditions with inadequate support for a poor wage, in effective bondage to a royalty-like corporate management that expects them to do what they’re told without question. Readers concerned about gender representation will be interested that all the characters that have a gender present as women, or did before switching. The story’s moral is intertwined with a current issue in modern politics; readers unwilling to read a cautionary tale about the fate that awaits an abusive 1% should steer clear. But Nix’ tale isn’t a retread fairy tale dressed up in SF clothing, it’s a brand-new work that nods respectfully to the source material without quite breaking the fourth wall, providing Grimm-inspired protagonists, villains, and just desserts in a world that knows Grimm stories but has apparently lost their message. “Pair of Ugly Stepsisters, Three of a Kind” is an outstanding story, thoroughly delightful, and offers an excellent reason to want to find and read more Nix.

Max Gladstone’s “The Iron Man” retells the Grimm Brothers’ ancient Iron John in a virtual world where tales of meatspace come down like an evidence-free oral history of a scarcely credible lost age. As in Cinder, Marissa Meyer’s cyberpunk Cinderella, the mystery for readers familiar with the original tale is not how it will end but how it will be remapped onto the alien world in which it’s retold. That is a fun world to see, with entertaining living-in-a-VR features. For example, trying to decrypt the secrets of the captive Iron Man hogs the processors and causes graphical jitters. VR kingdoms’ wealth isn’t measured in gold, but cycles. Rich characters can afford to render more gritty detail – in cheaply-rendered areas, faces have no wrinkles. Scars and limps and dirt and the irregular texture of tattered cloaks evidence luxurious wealth – a delicious reversal of fairytale tropes that signal rank and virtue with traits like clear smooth skin. Gladstone’s retelling preserves the simplicity of the original fairytale. Although Gladstone’s retelling keeps Iron John’s transformation in its conclusion, it provides a different mechanism: he’s not freed from a spell by the efforts and success of his protégé, but shares the protagonist’s journey to mature beyond his training into a human being, aged and imperfect.

Maura McHugh’s “Zel and Grets” retells the famous “Hansel and Gretel” in an interstellar society with widely-variant local laws, but no shortage of nasty criminals willing to misuse children who fall into their grasp. McHugh’s worldbuilding and villain development wonderfully support the story’s portrayal of the protagonists as dependent on their lousy parental figures, they make believable that the protagonists are truly stranded in the wilderness, and sell as convincing the protagonists’ helplessness before their captor after they find the house in the woods. The unfairness of their predicament is exacerbated by a legal system that accords them no rights, technologies that offer them little aid while working effectively against them, and records of their lives that are destroyed. As in the original, Gretel wins the siblings’ freedom at their darkest moment in a reversal that feels just like the story that inspired it. There is a structural difference between the original and the retelling: the original resolves the conflict with the parent who had the children stranded by killing her offscreen during the children’s exile, so that upon their triumphant return the children can be rewarded in a happily-ever-after with a loving parent in the home formerly ruled by their dead villain. Ahh, closure. In the retelling, Zel and Gretz don’t find their way back to their vanished home; we don’t learn whether their warden suffers judgment or is outlived by former victims. For all we know, the heartless crook still exploits children for profit. Although Zel and Greta convincingly win their liberty and find long-term safety, there’s a feeling of unfinished story that leaves one wondering. For a dark future tale, that may be appropriate; it is, however, no longer a cautionary tale against sacrificing children for convenience but a story about surviving abandonment. The departing message is, therefore, rather different than in the original. “Zel and Greta” is enjoyable not because it faithfully reproduces an ancient fairy tale, but because the author puts so much into the world and characters. A dark-future recreation of a story so well-known could easily have fallen flat had it not benefited from McHugh’s evident care to give life to characters and perspective to their problems.

“For Want of a NAIL” by Sandra McDonald and Stephen D. Covey sets their retelling of “The Nail” at a lunar space camp in a future in which everyone who’s anyone has a network access implant called a NAIL. The first thing that struck me about the story was its use of the first person, in stark contradiction to the fairytale canon and most stories in the volume. The narrator’s schoolchild voice, its overconfidence, and its abashed realizations are quite at odds with the omniscient narrative voice we’re accustomed to seeing in traditional myths and fairy tales. The lighthearted voice matches the authors’ short story that concludes on an upnote of young love, worlds away from the glum warning of the story on which it’s based. Although the story may be a lighthearted romp that resolves in the promise of young love, the plot problem develops from a series of setbacks that derive entirely from technological and engineering issues piling atop one another, making the story much more an SF piece than one might imagine in a short piece on a teen crush. In my view, McDonald’s and Covey’s story’s more fun to read than the original, which is a threadbare story that seemingly exists solely to reach its moral.

Dan Wells’s “The Shroud” returns to traditional fairytale third-person narrative with a high-tech retelling of the Grimm ghost story having the same name. In the original, a dead child reappears each night so long as his burial shroud is kept wet with tears his own mother’s weeping inspires the ghost to cry; when his mother is able to stop crying, the haunting ends. Wells’ retelling presents personality-preserving technology as an obstacle to spiritual transport to the afterlife, a selfish tool to keep loved ones near at their expense. Rather than resolving a mother’s grief to end a haunting, the story is about begging for release from what amounts to a technological prison that artificially prolongs a painless but incorporeal existence. To get into the story’s premise – that a spirit trapped in a high-tech bottle feels there’s more, if only the prolonging tech will be wiped – seems to require readers to accept that a machine capable of reading a dying boy’s brain signals so as to record and later operate his personality will, by doing so, also be capable of jailing a departing spirit. I could not give the story a fair shake because I could not buy the premise: if there are immortal spirits, why would a recording device that replicates the deceased’s mind prevent the spirit from doing whatever spirits do? The story’s power to deliver its technology-can’t-beat-death message comes from the heartbreak we see as we follow the boy’s mother – willing to sacrifice anything to preserve her taken-too-young child – as she goes further to accede to her dead boy’s wishes to set him free. We don’t see the boy’s mother heal or stop crying, as in the original, we just see her sacrifice more – and not based on evidence it would benefit her child, but solely on the child’s explanation she should do it because he asks. The element of recovery feels replaced with a demand for faith. Readers attracted to stories about faith will feel Wells’ piece on mortality and sacrifice right where it hurts.

Mike Resnick’s “Long Term Employment” retells the Grimm tale “Death’s Messengers” in a distant future whose interstellar civilization and its worlds full of humans and aliens keep Death even busier than in the Grimm original. Resnick’s tale adds a few beats to the original, providing color and character to people whose originals were two-dimensional sketches. In that respect, it’s better than the original. Two primary differences exist: with a few brush strokes Resnick adds a dismal overlay to his world (the original is colorless, having only a road with some roadside rocks), and in a few lines of dialogue transforms a fatalistic ending to an uplifting conclusion with some real feeling. Further description of the differences, particularly the story’s conclusion and reversal, would spoil the novelties in Resnick’s reinvention. It’s a fun short, worth reading, and eminently deserving of inclusion in a collection of Grimm tales reset in the dark future. Readers keen to see the original story’s moral preserved will be disappointed: Resnick discards the original’s fatalism for a story in which mortals can change their fates and the world is magic. In the dismal future, we’ll need to believe that to survive.

Inspired by “The Six Swans,” Nancy Holder’s “Swan Dive” is not the original retold in another time but an entirely different story. Many of the story’s features recall an English possession during the Age of Empire, but not the cloaking device or the rocket. Instead of following the trials of the virtuous maiden, “Swan Dive” shows a British officer’s struggle against the Empire that holds his loyalty but has consigned him to an ignominious post on a desert isle and expects him to execute for treason the woman who has so swiftly captured his heart. Perspective isn’t the only change in Holder’s retelling: the male lead isn’t a king, the maiden’s decision to hold her tongue isn’t some outside compulsion but her own stratagem; moreover, the character that must show virtue to prevail isn’t the leading lady. For all its changes, the original virtue-is-rewarded moral remains: a helpless protagonist demonstrates self-sacrifice, inviting rescued by an admirer of his steadfast virtue. It’s a fun read, true to the original moral, retold in a world as dark as the original.

Where the Grimm brothers’ “The White Snake” opens on a servant awaiting a king’s table in a castle at peace, Dana Cameron’s “The White Rat” opens in a sheriff’s office detaining a thief on a space station belonging to a Corps long at war with aliens it remains unable to defeat. Rather than follow a servant who gained the power to understand animals, Cameron’s retelling follows the sheriff whose thief detainee understands the station’s bomb-sniffing rats (and a contraband monkey, and so on). In the dark future neither the sheriff nor her detainee are granted a boon by their masters or freed from service: both live indentured to a militarized corporate government that is willing to vent offenders into space for wasting corporate resources, and perfectly happy to treat disparagement of its incessant war effort against the squids as though it were treason. Unlike the happy servant of the original story who achieves great things because of his secret ability to speak with animals, the detainee in Cameron’s tale is quickly outed as able to speak with animals and regarded with suspicion, fear, and (by the corporate administrators interested in surveilling their alien enemies) avarice. In the finest No Good Deed Goes Unpunished tradition, the protagonists’ success in saving the station from disaster only invites more disaster; the protagonists are propelled from problem to problem while the antagonists are elevated and emboldened. “The White Rat” is a first-class example of a Grimm tale retold in a dismal future; Cameron’s sympathetic protagonists deliver the story’s original moral (about good deeds bringing good results despite everything) in an enjoyable manner. Like Resnick’s “Long Term Employment,” “The White Snake” makes no effort to provide a strictly Science Fiction basis for its primary elements – but who can fault a fairytale for apparent magic?

Carlos Hernandez’s “Origins” retells the Grimm story “The Star-Money” (or “Star-Talers”) on a corporate-run settlement (“Origin City”) where workers lured to the Moon by the promise of riches die homeless and freezing as low-gravity atrophy degrades their work capacity toward fatal unemployment. It’s an outstanding backdrop to create both dire need for help and harsh costs for providing what on Earth might seem an everyday kindness. Unlike the original Grimm tale, “Origins” doesn’t turn on readers’ faith in God to give the resolution power: instead of being rescued from the consequences of her selfless charity by divine intervention, Hernandez gives his human protagonist exactly the result one would expect in the frozen periphery of an unheated colony’s unrecycled surplus structures. “Origins” complicates the story with two points of view and a worldbuilding effort that gives perspective on the main characters’ predicaments and the personal cost of every sacrifice. The result is a richer, more complex, and more interesting story with a moral that feels more believable: charity might not inspire divine intervention, but it inspires witnesses to even greater charity. Hernandez’ story preserves many of the original tales’ elements, but presents them in a more interesting world and uses them to teach a moral that stands up better to readers’ experience with the world and its consequences.

John Langan’s “Angie Taylor in: Peril Beneath the Earth’s Crust” is based on “The Brave Little Tailor,” about the tailor whose clever scams eke him through a series of perils and land him in a marriage to a king’s daughter (who’s unexcited about her suitor, and much less so once she discovers he’s a lowly tailor). Langan’s tale presents an engineer whose cleverness in her side-work on an improved welding torch prepares her to succeed as a genuine hero on (and under) an Earth whose interior contains a hidden world (and a concealed invasion force). The story’s departure in voice and tense from the third person and past tense gives it an unfairytale-like feel: it opens in present tense just before the climax, jumps to past tense for backstory, then resumes in present tense. Although jarring to one’s current fairytale sensibilities, who’s to say what the fairytales of the dim future should look like? On that note, the story isn’t set in the dismal future so much as an alternate past with a hollow Earth; but surely they need fairytales there, too. The biggest difference in the stories is the quality of the protagonists’ character. While Langan’s protagonist is happy to stretch the truth for a good tale, she delivers results without conning anybody. In this, she’s a more sympathetic character than the original. The eponymous Brave Little Tailor deceived others into undertaking effort for his benefit, and through his representations about himself he became primarily a con-man – perhaps attractive as an asshole anti-hero, but not a character to hold out as an example to children near whom you will have to live as they mature. Where “The Brave Little Tailor” ultimately succeeds by terrifying critics with deceptive bluffs, “Angie Taylor” succeeds by delivering results with a combination of her hard-won skills and new technologies she invented herself. “The Brave Little Tailor”’s victory condition involves inherited wealth and a princess trapped in an undesirable but inescapable marriage to the protagonist, but “Angie Taylor”’s superior victory comes from earning promotion to a dream job and, with it, authority to do what she wants her way. By making the tall-tale-telling Angie Taylor sympathetic, Langan’s cleverness-beats-brawn lesson has a more honorable feel than the original – a real improvement, and well-suited to prepare people to combat misery in the dismal future.

Jeffrey Ford’s “The Three Snake-Leaves” retells the original fairytale inside a larger framing story that involves a hidden garden whose robot inhabitant shares tales with the protagonist when he visits – including “The Three Snake Leaves,” which the robot explains is related to the protagonist’s own problems. The framing story includes some delightful world-building: a miserable, impoverished world ruled by desperation and greed has an unemployment rate so high denizens of “the crumble” envy the protagonist’s impoverished mother’s employment at a sapping plant that drains the imagination until it burns out and kills its workers. Dark and awful, just like the doctor ordered. The retelling contains elements as sad and dark as in the original, but offers some hope for redemption; it ends with an up-note the original Grimm tale lacked in its harsh-justice conclusion. We’ll need that in the dismal future.

Peadar Ó Guilín’s “The Madman’s Ungrateful Child” is a post-apocalyptic story about a woman who abandons the safety of her captor’s bunker to seek a mother she hopes survived the attack that laid waste to civilization. The Grimm tale on which it is based is “The Bremen Town Musicians” – a story in which doomed animals delude themselves into believing they can make a living as musicians in Bremen, only to save themselves by overtaking a provisioned dwelling by fooling its bandit inhabitants into believing they represent a supernatural threat too dangerous to challenge. In the original Grimm tale, everyone is fooled: the animals have an unrealistic goal, but nevertheless succeed because their targets are fools easily persuaded to flee their home and stay away out of superstitious fear. Ó Guilín beautifully captures the everybody-is-fooled aspect of the story while providing credible psychological and technological reasons to credit the characters’ convictions as realistic responses to their world. As in the original, the characters live in a dangerous world of privation, and take risks to address their wants. Ó Guilín gives the original farce a dark edge; by the time the protagonist tears away the illusions and understands what the truth is and how she was mislead, her world has become a much more deeply sad place to inhabit. Anyone who likes dark tales will enjoy Ó Guilín’s take, darker and more complex than the original.

In “Stories of Trees, Stories of Birds, Stories of Bones,” Kat Howard retells “The Juniper Tree” with an SF explanation for the talking creatures. The retelling has a travelogue feel: we see and discover colorful things but never suffer any fear something might happen to the protagonist, and we don’t have to watch her make any hard decisions that might teach us who she is when the chips are down. Howard weaves original story elements into the retelling, buttressed with an SF explanation for the messages she understands from the birds and trees. By depicting the original story’s elements as discoveries incidental to the protagonist’s job, Howard conceals their connection to the story problem – something the original story’s supernatural explanation prevented – which facilitates an eventual reveal (the original story only delivers an escalating series of supernatural resolutions). Key elements change in the retelling. Instead of Nature conspiring to deliver justice to wrongdoers, ultimately crushing a child-murderer with a bird-borne millstone, the retelling follows an eccentric millionaire’s employee on an ongoing project to record the stories of the trees and other living things on her employer’s extensive property, until at last the employer gets resolution over her brother’s long-ago murder. Howard’s version is more interesting and complex than the original, but readers who demand a story that climaxes with the protagonist’s hard, character-defining choice in the story climax will not find the improvements on the original go far enough. The original twist-ending (bandits give up reclaiming their home from the harmless but presumed-dangerous would-be musicians) is replaced with the reveal that allows the protagonist’s employer to find peace.

In “Be Still, and Listen,” Seanan McGuire uses language with a poetic, oral-delivery cadence whose traditional-story feel is buttressed by elements like intergenerational curses, the futility of fighting fate, and the price of failing to know yourself – ideas all so ancient McGuire easily sells a fairytale feel despite the uncharacteristic-for-a-fairy-tale first person voice. Anyone fond of language should enjoy McGuire’s lyrical mode of address. It’s wonderful to read. “Be Still, and Listen” provides a fun journey to discover what is so obvious to the narrator that she doesn’t bother to lead with it. It also offers the reader some unexpected fun in the fact the account occasionally gives instructions to its listener or addresses the narrator’s daughter as “you” – it nudges the reader to accept a relationship to the narrator, and pulls the reader into the story by involving the reader in the narrator’s plans. The use of events recalled in past-perfect tense, to deliver backstory, feels like it pushes the action into the background; this isn’t an edge-of-the-seat thriller but a family drama with a rich, gloomy mood. Many readers won’t recognize “Little Briar-Rose” as an alternate name for the tale they mostly know as “Sleeping Beauty” when they read the story’s inspiration, so the story gains extra power by raising questions what the story is about before revealing exactly which story “Be Still, and Listen” sets out to invert. And it is an inversion: the original depicts a hero-prince taking action to win a prize (the princess, and eventually the kingdom) while the princess, despite having suffered the effects of an undeserved curse, passively accepts what awaits her when the curse is lifted … without ever making any choice at all. By contrast, McGuire’s retelling purports to recount the true story – what really set off the disaster, how the fairies actually came to be involved in the story, why mortals misunderstood the fairy sleep as a curse, and the fact the real choice lies with the women of that family and has done so for generations. Best of all, McGuire’s story inverts the outcome: her protagonist schemes to reject the busy, ever-running mortal life she grew up urged to pursue, in order to reclaim the lost fairy sleep mortals regard as a curse, but which will save the world. In doing so, McGuire offers a moral with more grip than the original. The original seems to offer as its moral that if you are a brash young prince you should ignore the dire warnings of local elders because you could luck out and discover that the day you walk into the enchanted killing briars is the day the curse lifts and everyone will mistake you for a great hero instead of recounting afterward how you died painfully, leaving your unrecovered remains to fertilize the enchanted thorns. McGuire instead suggests something of more practical use to the modern reader: our busy, hectic, frightening world needs people to learn stillness, and we can learn wonders if we choose to spend time listening. Readers who loathe Sleeping Beauty because of its passive female lead will love this ‘True Story Of The Briar Rose’ for its flat rejection of the traditional version of the tale, and its demand the story have a protagonist who actually accomplishes something. Recommended.

The Grimm Future promises fairy tales for the dismal future, and it delivers. From the book’s gorgeous physical presentation to the inclusion of traditional Grimm fairy-tale inspirations after each original story, the project seems rich with decisions that feel so obviously correct looking at the final product that one can’t help waiting for Underwood’s next project. Whether you buy a physical copy or an electronic one, the anthology is much denser in recommended stories than one finds in nearly any short story collection. It’s a terrific work. Anyone who loves fairy tales should be told about this, or receive it as a gift. Of course, the Fae among you may prefer to bargain with them over it … or wager it in a game ….

(Note: Product Contains No Iron.)

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

The Grimm Future

The Grimm Future