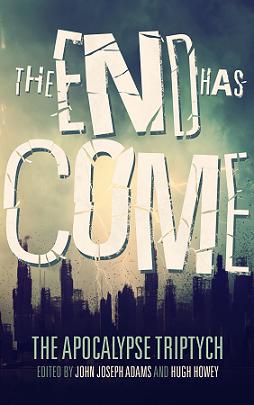

Edited by

John Joseph Adams and Hugh Howey

(Broad Reach Publishing, May 2015)

Reviewed by Douglas W. Texter

The End Has Come: The Apocalypse Triptych, edited by John Joseph Adams and Hugh Howey, delivers a pretty mixed collection of short fiction. Many of the entries didn’t offer what I expected here: protagonists struggling heroically against some aspect of the apocalypse. Indeed, the protagonists in too many of these tales seemed to just roll over and get ready to expire or accept fate. Things just happened to them, and little moral agency was shown. This lack of agency in settings that brim with choices and consequences really disappoints. On the other hand, in the very best of these stories, the protagonists faced and navigated very difficult choices. These kinds of tales make the collection worthwhile. Finally, one of these stories delivered something I truly did not expect to encounter at the apocalypse: thigh-slapping humor. What the heck! After all, and with apologies to Michael Stipe of R.E.M., it’s the end of the world as we know it, and I feel fine.

In “Bannerless,” Carrie Vaughn takes us to a very soft post-apocalyptic world in which people live in “households” and have to apply for banners in order to have children. When the story opens, Enid and Bert, two investigators for a regional committee, are walking to Southtown to check into an unplanned and illicit pregnancy. Enid and Bert function as an odd couple in a few ways. This is Enid’s last investigation, and it’s Bert’s first. She provides the brains of the outfit, and Bert, much bigger and carrying a staff that serves as a weapon, offers the brawn. When they arrive in Southtown, the investigators learn that Aren, the pregnant young woman, cut out her birth-control implant in order to have a child with her boyfriend, Jess. The heads of the household—which seems to function similarly to what we would call an intentional community or co-op—Frain and Felice, are not pleased to have an investigator here. Through discovering why Arlen conceived without a banner, Enid uncovers issues much bigger and more serious than just the pregnancy itself. This tale was interesting, but I felt let down in a couple of ways. First, I wanted the stakes of this story to be higher. Certainly, the household suffers consequences, but I wanted this incident to pack a larger societal punch. Second, I found Enid a very interesting character to begin with, but I didn’t see her develop very much. She began the tale world weary and ended it the same.

Megan Arkenberg, in “Like All Beautiful Places,” doesn’t really present a story of a post-apocalyptic West Coast. Rather, she gives us a set of images and memories. The tale, much of it told in back story, is fairly simple: San Francisco has basically ceased to exist because of a massive earthquake. The female protagonist works for a scientist named Lena, who operates a kind of virtual reality experiment out of a shipping container in Oakland. Apparently, Lena wants to virtually recreate San Francisco before the fall by tapping into the memory grids of those who knew it well: hence, the protagonist’s participation. Much of the story concerns the memories of the protagonist. We get mostly the pre-apocalyptic memories of a bad relationship with a hipster named Felix. These memories are pretty pedestrian: a boyfriend who seems somewhat manipulative and a girlfriend who packs resentment in her purse but can’t quite make up her mind about what she wants. There’s something revolutionary here? Fortunately, the earthquake wipes out the banality of their cohabitation. I have to be honest here: this story didn’t offer me very much. This waif-like (I can almost smell the patchouli and cloves) protagonist never really takes much action. And I found the set up a little unbelievable. San Francisco doesn’t exist anymore. Gone. Millions are presumably dead. My guess is that much of the rest of the West Coast has been destroyed by Mother Nature. And science is offering a virtual re-creation of a city? I can’t help but think that there would be more worthwhile projects that would need to be undertaken and more worthwhile stories that could have been written.

“Dancing with a Stranger in the Land of Nod,” by Will McIntosh, is a powerful story, a piece of moral fiction that deals with love, caretaking, and the consequences engendered by these actions. A plague has ravaged the United States. Ninety-seven percent of the population molders in the grave. Many of the survivors, if you can truly call them that, exist in a catatonic state. When the story opens, Teale, one of the survivors, drives through a frozen wasteland, listening to the closing theme from the Lion King. With her ride her catatonic husband, Wilson, and her catatonic children, Chantilly and Elijah. The car breaks down, and she hikes along the frozen interstate to try to get help. A mini van, driven by Gill, who also transports a catatonic family, stops. Gill helps Teale, and she brings her family with her to Gill’s abode. There, the two caretakers develop romantic feelings for each other. The problem, of course, is that both have family members, including spouses, who are still alive. Teale faces a decision about whether to pull the plug on her family and start a new relationship. I won’t tell you what decision she finally makes, but I will say that this tale deals with morality and decision making in the face of almost ridiculously terrible circumstances. This story possesses gravitas.

In “The Seventh Day of Deer Camp,” Scott Sigler tells a very interesting first-contact story. George and his four friends vacation at a snowy Upper Peninsula deer camp when the unthinkable happens. Aliens storm the Earth. These aliens—as is almost never the case—are completely outgunned by Earth’s military forces. While the aliens kill millions in the assault on Terra, human pilots and missiles blast the alien ships. One ship, though, crash lands at deer camp. All the aliens on board, except for eleven children, the sole survivors of the entire alien race that came to earth, die on impact. Some members of George’s hunting party want to blast the alien kids with their rifles. But George, a father himself, intervenes and protects the children. Here’s where things get really weird and deliciously postmodern. An older person at the hunting camp is sick. George calls not the paramedics but a local news station and tells them to bring an ambulance and a snowplow. They arrive, and George announces to the entire world the existence of the children. In this wired postmodern environment, the alien attack didn’t bring about some kind of world government and peace among nations. Rather, the event stirred people’s paranoia about government. Why didn’t national governments warn people about the impending attack? What will happen to the children? Will they be carved up in some secret government facility? In this age of Youtube videos, George becomes a kind of celebrity because he stays with the children and refuses to allow any government to take possession of them. The world checks in with him every day to make sure that the government hasn’t intervened. I liked this story very much. As was the case with the last tale, “The Seventh Day of Deer Camp” deals with moral decision making and the consequences of very difficult decisions. George protects the children, but, because of fears of contamination, can’t go to see his own wife and children. He is both caretaker and prisoner. I strongly recommend this story.

In “Prototype,” Sarah Langan tells the tale of a far-future post-apocalyptic world in which cyborgs constitute the dominant species. Humans, what’s left of them, are kept in deep tunnels and harvested when appropriate. The protagonist is an A-class cyborg who has a dog named Rex. Well over a thousand years old, the unnamed protagonist actually remembers what life was like before the asteroid strike on earth over a millennium ago. When we meet him, he’s on the desert-like surface of Earth waiting for a sand ship to pick him up. He’s been testing above-ground survival-suit prototypes. This tale is low on plot and heavy on atmosphere. And that atmosphere is lonely. What we mostly get is first-person reflection on how this world of underground dwellings and humans as breeding stock came to be. One can’t help think of the Matrix. We also get the memories of the protagonist, who recalls that he was once human and had a family. I can’t say that much happens here or that the protagonist grows and develops. Neither of these possibilities happens. I do like the concepts here: the far-future SF, the telling of the tale from the cyborg side of the equation, and the seemingly eternal and existential angst of the protagonist.

“Act of Creation,” by Chris Avellone, delivers a view of Agnes and Reeves. The former is a scientific investigator. The latter a Sensitive. The story opens and closes in one location, a cell in which Agnes visits Reeves. Apparently, in this world Sensitives were created to fight a kind of alien menace, although I’m never quite sure what the battle was. At the beginning of the tale, Reeves, who barely looks human, clings to the ceiling of the cell. Reeves, who can read minds, is an absolute mess. Along with other Sensitives, Reeves was created to fight the alien menace, and he’s transforming into something else, although I’m not quite sure what. I was disappointed by this story for several reasons. There’s no character development at all. And all the events take place in what is a white room. Agnes, since she’s the POV character, functions as the protagonist, but she never really does anything other than react to Reeves. I’m not sure when we are or where we are. If this story were a movie, it would be eye candy, but since it’s print fiction, it falls pretty flat and fails to deliver much to the reader.

In “Resistance,” Seanan McGuire give us one of the most interesting portraits I’ve ever seen of the mad scientist whose work has basically destroyed humanity. We encounter here a story of a very different kind of Dr. Frankenstein or Dr. Strangelove. Dr. Megan Riley, who suffers from an extreme form of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, headed up Project Eden, which was designed to produce fruits and vegetables that could survive in a rapidly changing global environment. Unfortunately, Project Eden actually produced a “flesh-eating strain of hyper-virulent bread mold first.” The fungus wiped out ninety-eight percent of the population, including Dr. Riley’s wife, Rachel, and the couple’s daughter, Nikki. Ironically, Dr. Riley numbers among the two percent of the population immune to the fungus. Riley had not directly caused the disaster; her team, which falsified data, had been the culprits. But the head of Project Eden bears some responsibility because her team hadn’t told her about contamination because they feared that her OCD would make Riley shut down the work. The story opens with Riley in a military hospital, being told that she’s charged with treason by three former nations: the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. A colonel, a very strong woman who has lost children because of the fungus, gives Riley a chance to redeem herself. The conceit of the fungus is quite interesting. The character is also fascinating: a Ph.D. lesbian with OCD. But the climax of this story is much too easy, and there’s so little agency here: the protagonist, whose work has wiped out most of North America, is handed almost on a silver platter a chance for redemption. Riley doesn’t earn this redemption; it just shows up. In addition, the protagonist isn’t very active. We hear of the disaster, and we’re told of the battle that will take place in the future. But part of the fun of epidemic stories is seeing the scientist as warrior (even a defeated one). We don’t see that kind of action here, and that’s a shame.

In “Wandering Star,” Leife Shallcross takes us down under to Australia, where a meteor will soon impact the eastern portion of the continent. For a moment, I was reminded of that other Australian-set story about the apocalypse, On the Beach. Absent from this story, though, are compelling characters who try to make meaning for themselves and search for survival before everything ends. The story is really a set of reactions on the part of a woman, a mother and wife, who learns that catastrophe looms in the sky. These reactions or vignettes, which aren’t very conclusive and don’t involve much action, are interspersed with catalogue copy from a museum exhibition set in the future. The copy details portions of a quilt that the mother made for her daughter, Jessica. Even this feature proves inconclusive. Did the family survive? We don’t know. I believe that the ambiguity here was intentional and meant to tease us. It simply frustrated me. Except for one particular instance in which the protagonist lies to her own mother, we don’t really see any struggle here: no heroism or cowardice, no battle against death, no real conflict. Perhaps others will enjoy this story; I didn’t.

“Heaven Come Down,” by Ben H. Winters, is truly a gem. The fluid and poetic writing here reminds one of Bradbury at his best. This story tells the tale of Pea, a thirteen-year-old girl left alone after everyone on her planet dies. Presumably settlers from Earth, the people on this planet constituted half of an exodus. The other half continued on from this world and promised to return when they had found a better planet and established themselves. They never came back. When the story opens, Pea is hearing what she thinks is the voice of God. The supposed Prime Mover tells her to begin acts of creation and destruction. The story here becomes almost biblical in terms of the acts that Pea engages in; with her mind alone, she destroys all of the rubble from the old civilization. After wiping the slate clean, she literally re-visions the whole planet, creating a new world. God here turns out not to be a divine being, but something else, something very surprising. “Heaven Come Down” is very, very high concept SF, dealing with the evolution of an entire species. This tale stands as one of the very strongest in this collection.

David Willington, in “Agent Neutralized,” presents the story of Whitman, who had been a field agent for the CDC before the zombie apocalypse. The story is split in two. Part of the tale—presented in flashback—tells the story of how Whitman was turned into a scapegoat by the post-apocalyptic U.S. government (which operates underground, beneath Washington, DC). Although his scheme to prevent the further spread of the disease by walling off cities saved lives, it also cost lives in the rioting in the hospital camps erected outside the cities. The other part of the story—interspersed with the flashbacks of Whitman’s political and career fall from grace in front of a Senate committee—functions as kind of a Mad Max tale. Whitman, having been demoted by the committee and functioning as a driver shuttling newly identified positives (those not yet infected but with the potential to be infected) from the cities to the hospital camps, drives two passengers from Atlanta to Florida. These passengers, a young woman named Grace and a boy named Bob, are literally along for the ride when Whitman has to fend off road-pirate motorcycle gangs. The action in this tale is quite exciting and pretty blood soaked, but I’m not sure that the story transports us to any place we haven’t seen before, either in print or in film.

“Goodnight Earth,” by Annie Bellet, reads like a novel excerpt or opener. Bellet takes us to a fairly far future Earth in which, I believe, the moon has exploded long before the opening of the story. Earth is now surrounded by a ring, which occasionally rains down asteroids. The United States has ceased to exist. The story opens on a very small, flat-bottomed steamboat, the Tarik, on the Missip River, which obviously is the Mississippi. We’re in Mark Twain country, but the protagonist doesn’t resemble Huck Finn. Or does she? Karron, the friend of Ishim, the boat’s owner and captain, is a former War Child. When she was very young, nanotechnology was implanted in her and had made her an unnatural born killer. She hasn’t engaged in mayhem in over fifteen years. The boat carries four passengers: Nolan, Jill, Oni, and Bee. The first two are adults who eventually try to hijack the boat when it reaches a bridge on the river. The latter two, much to Karron’s surprise, are also War Children. During the hijacking attempt, when two other men wait for the boat at the bridge, Karron goes into War Child mode and, with the help of Oni, who distracts Jill with a blanket, engages in a killing spree. After the blood has stopped flowing and staining the ship’s wooden beams, Bee tells Karron and Ishmi that Jill had kidnapped them and was preparing to sell them to a baron. Oni shares with Karron and Ishmi a map showing the location of Sanctuary, a place in which the nano-technology that both enables and haunts Karron can be removed. While I enjoyed the conceit and action of this story, I feel as though I’m just being set up for a much longer quest narrative, rather than being given a complete stand-alone tale.

In “Carriers,” Tananarive Due presents a story about parenthood after the apocalypse. In 2055, Nayima, a woman living on a farm in the Carrier Territories of the Republic of Sacramento, discovers that she has a biological child. Well, sort of. Nayima—along with her once-upon-a time lover, Raul—is a carrier of antibodies that were used to destroy a plague that ravaged the United States. Carriers seem to have been treated like objects by the government. Now, the few remaining carriers have been given—through a Reconciliation—land or permission to live in communal situations. Raul visits Nayima and tells her that a child has been produced from her eggs and his sperm. Although I found Nayima an interesting character and the conceit of “Carriers” intriguing, I didn’t like this story very much because there’s so little agency on the part of the protagonist. The character basically reacts throughout the entire piece. Yes, we get her thoughts, but we don’t get much action or real decision making from her.

Robin Wasserman, in “In the Valley of the Shadow of the Promised Land,” tells a very strange post-apocalyptic story. Long before the tale takes place, a leader of a cult predicted that meteors would fall from the sky. Taking the name Abraham, the leader moved all of his people into a compound to wait for the end of the world. In a very nice and very ironic coincidence, it turned out that the leader was right. A meteor smashed into the Earth. The cult leader eventually departs from the compound, and his son, who calls himself “Isaac,” becomes a leader every bit as strange as his father. The members of the cult spend a decade in their compound and then emerge into the new post-apocalyptic world. Isaac, who has two sons, Thomas and Joseph, ages and starts to become senile. For years, members of the cult present a pageant that replays the story of this Abraham and this Isaac. Then, a stranger—with a very interesting identity and relationship to Abraham—arrives on the scene. The writing here is superb, and the story deals admirably with the concepts of truth, memory, fatherhood, deceit, and cultic behavior.

In “The Uncertainty Machine,” Jamie Ford presents a macabre steam-punkish apocalypse. It’s 1910, the year of Halley’s Comet, and a charlatan named Phineas Kai Rengong sits in an underground comet shelter beneath Seattle. A comet has indeed hit the earth, and Phineas, a consummate swindler, becomes trapped in the shelter. With him sit the corpses of two female twin followers of his who essentially died from bad opium trips while servicing him. Phineas while in prison in Hong Kong had met Professor Frank Ser Ling, who had created an I-Ching Machine that spits out answers to questions. Phineas had used the machine to convince his followers to give him money to build his shelter. While disaster reigns above ground, Phineas slowly starves to death and goes insane in the shelter. A lot of the story is told in flashbacks and exposition. But two qualities save this tale from passivity. First, the author really knows the gilded age. The back story teems with material about miners, anarchists, coolies, and everything else from the age of homeopathic medicine and J.P. Morgan. Second, this character truly is fascinating. He is a likable scoundrel. I recommend this story for its window into the detritus of the early twentieth century and its unflinching portrait of a con artist.

Elizabeth Bear, in “Margin of Survival,” presents a strange story set in an area of the world that has been somewhat apocalyptic in terms of its politics for the last twenty-five years: Serbia. The country is never named, but the name of a kind of automated lighthouse, “Zombie Light” (Svet Nezhyti), gives away the location. The protagonist, a former economics graduate student, Yana, forages for food for herself and her sister, Yulianna. The latter, we learn, is sick in a shack. While foraging in a bunker, Yana hears a cry from someone, a woman, who has been tied up. Yana frees the woman, who, as luck, or perhaps, the supernatural would have it, possesses the same name as Yana’s sister. The two engage in conversation about the apocalypse. Then they leave to return to the shack. This second Yulianna disappears. Yana returns home to find her Yulianna in a very death-like condition. The ending reminded me of Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily.”

“Jingo and the Hammerman,” by Jonathan Maberry, is delightfully funny. Self-help meets the zombie apocalypse. Imagine two survivors of the zombie apocalypse after which ninety-nine percent of the U.S. population now consists of the walking dead. One member of this odd couple, Moose, is a former high-school football coach. The other, Jingo, is a trust-fund baby. The two men serve on what could best be called a zombie reclamation squad. Jingo functions as a cutter, hacking off the hands and one leg of each zombie. When the undead person collapses, Moose finishes the reanimated corpse off with a sledgehammer blow to the head. As the two toil away under awful conditions, they engage in philosophical conversations about the meaning of the zombie apocalypse for the future of humanity. A fan of self-help guru Tony Robbins’ books, Jingo waxes poetic about how the apocalypse could actually have positive effects on human development. The conversation goes on and on until Moose spots a zombie who resembles none other than a very tall self-help guru. This tale is very funny. The characterization is wonderful, and the irony here is palpable.

In “The Last Movie Ever Made,” Charlie Jane Anders presents a completely postmodern, post-apocalyptic tale. The apocalypse this time is an odd one. No meteorite, no zombies, and no viruses. A sonic weapon has misfired and made the entire world population deaf. Set in and around Cambridge and Boston, “The Last Movie Ever Made” features the tragicomic adventures of Rock Manning, a filmmaker who is asked by an old high-school friend, Ricky Artesian, now a member of the post-apocalyptic government, to make a film that shows the government in a good light. Rock agrees, but his friend Sally is upset because the government, the members of which wear red bandanas, has killed her boyfriend. The Bandannas occupy the cities, and the army, using mechanized fighting machines that are a cross between Terminators and Transformers, occupies the rest of the country. Somehow getting hold of the Oscar Meyer Weinermobile, Rock makes a movie called Ballpark Figure that ends up having the Bandannas and the army come into conflict. Functioning as a postmodern pastiche that has echoes of Tarantino and Tom Robins, the tale is a bright electric kool-aid acid test, but a test that has its protagonist take a very strong and costly stand against authoritarianism.

“The Gray Sunrise,” by Jake Kerr, concerns the life dream of Don Willis. When he was a little boy, Don dreamed of having a sailboat after seeing one on television. Following the advice of his father, Don hangs onto this dream throughout his life. When he finally has gained the boat of his childhood imaginings, he has lost his wife to divorce but still clings to his teenaged son, Zack. When the story opens, an asteroid heads toward an impact in North America. Don grabs Zack, who seems more interested in video games than he does in survival, and heads to the pier, to his boat, The Southern Cross. Sailing down to South America, Don and Zack have to battle human predators, storms at sea, and, of course, the results of the asteroid impact. This wonderful tale emphasizes the importance of chasing one’s dreams and highlights the institution of fatherhood, a subject that has not been treated very well in the culture lately. I highly recommend “The Gray Sunrise.”

“The Gods Have Not Died in Vain,” by Ken Liu, gives us a tale that disturbs in terms of its projection of the future of humanity and perhaps its disembodiment. A teenaged girl, Maddie, lives with her historian mother in post-apocalyptic Boston, the population of which has doubled because of an influx of refugees. A war has occurred, caused by the uploading of human consciousnesses, including that of Maddie’s late father. These consciousnesses became almost godlike and were destroyed during the ensuing intercontinental conflict. Add to this event the serious degradation of the environment before the war and the collapse of U.S. infrastructure. Now, in the postwar world, robots designed by a corporation called Centillion, take over human jobs. In a chat window, Maddie discovers a sister, Mist, an AI offspring produced by her father’s uploaded consciousness. Maddie gives Mist a body by downloading her sister’s consciousness into a small robot that she (Maddie) builds. But Maddie discovers through a taste test with a tomato that, in some ways, Mist doesn’t need a body. She has experienced through cameras, sensors, and microphones much more than her human sister has. Maddie and Mist grow concerned that the decaying postwar world will need to call on the gods—AIs—once again, and both sisters want to prevent this occurrence. Everlasting, Inc., headed up by Adam Ever, a friend of Maddie’s late father, is launching a “Digital Adam” project. Ever, who has died in human form, has become a god, an AI. Ever believes that the future of the human race lies in the project of becoming disembodied since embodied human beings consume too many resources. This tale, considering as it does post-body humans existing in a Matrix-like world, is fascinating, yet there is no real conclusion to this story. Mist and Maddie simply wait for the new future. I wanted more here.

In “The Happiest Place,” Mira Grant takes us to a very unlikely and quite haunting setting for the apocalypse: Disneyland. Amy, the head of Guest Relations, becomes the mayor of the Magic Kingdom shortly after a virus eradicates almost all of the U.S. population. Living in Walt Disney’s apartment, Amy helps the survivors of Disneyland forge a kind of life in the midst of the devastation. Unfortunately, one of Disney’s generators conks out, and Amy must lead a raiding party to a hospital in the outside world in order to scavenge the necessary parts to keep Disney’s lights on and food cold. The story’s final scene in the Haunted Mansion is absolutely wonderful. I highly recommend this story.

“In the Woods,” by Hugh Howey, tells a double POV story. The first POV is that of April, who, along with her husband, Remy, wakes up in an underground chamber in Colorado only to discover a catheter and IV tube inserted into her body. She and her husband have been asleep for five hundred years. She opens a letter left to her by her sister, who wants her to exact revenge against the people who caused the apocalypse and who also slept through the centuries. The perpetrators of this holocaust, April’s sister says, are alive and in Atlanta. Remy and April then immediately find themselves under attack by several savage humans who can only utter, at various volumes, the phrase “Feef-deer.” The scene and POV then shift to, presumably, coastal Georgia, although geography might have changed during the centuries after the apocalypse. Elise, who hunts deer with a bow, finds Remy and April, who have been hiking across America for several years with murder in their hearts. Elise, knowing that the husband and wife hail from a silo, brings them to the community’s leader, Juliette. There, April and Remy take revenge on Juliette. This story didn’t work for me because we never really know what’s happened. We don’t see April and Remy on the trail for years. We don’t really know Juliette or Elise. Because we don’t get to know any of the characters at all, I can’t feel very much for any of them.

In “Blessings,” Nancy Kress tells a provocative story about a post-alien-invasion Earth. The Dant, an alien race, have found Earth and bestowed upon it a very mixed blessing. These aliens—who are a cross between a flower and an octopus—helped Earth reduce CO2 emissions, and they’ve also helped humans—or at least most of them—become less violent. People now live in Mutuality in rural villages. The Dant, while at first glance appearing as saviors of the human race, have another, entirely malignant agenda: the pacification of the human race through dumbing it down and the ultimate extermination of it through the killing of the sex drive. The Dant have changed human DNA. The aliens have also instilled in human beings a new reaction: Extreme Involuntary Fear Bradycardia. People freeze and can’t breathe correctly when violence occurs. How convenient for the Dant. Kress tells the story through two POV characters. The first is Larry Travis, who is what passes for a scientist in the post-Blessing world and who has slowly come to realize that the Dant don’t want humans to possess any science or technology. The second is Jake Martin, who possesses unchanged DNA and serves as a resistance fighter against the Dant. Having lost all the members of his unit to a Dant attack, Jake falls in love with Larry’s Daughter, Jenna, who also seems less pacified than most humans. This story was quite intriguing because it challenges notions that being peaceful is always a good thing. Kress seems to make the argument that human aggression and human progress are linked on a very deep level. Take away one, and you remove the other. History, which shows that some of the greatest technological leaps we’ve ever made have come because of war, seems to bear out Kress’s thesis. I recommend this story.

The End Has Come:

The End Has Come: