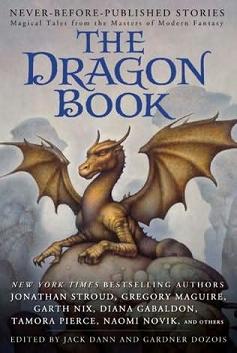

The Dragon Book, edited by Jack Dann and Gardner Dozois

The Dragon Book, edited by Jack Dann and Gardner Dozois

Reviewed by Carla Billinghusrt and Robert E. Waters

Ace hardcover (November 2009)

“Dragon’s Deep” by Cecelia Holland

“Vici” by Naomi Novik

“Bob Choi’s Last Job” by Jonathan Stroud

“Are You Afflicted with Dragons?” by Kage Baker

“The Tsar’s Dragons” by Jane Yolen and Adam Stemple

“The Dragon of Direfell” by Liz Williams

“Oakland Dragon Blues” by Peter S. Beagle

“Humane Killer” by Samuel Sykes and Diana Gabaldon

“Stop!” by Garth Nix

“Ungentle Fire” by Sean Williams

“A Stark and Wormy Night” by Tad Williams

“None So Blind” by Harry Turtledove

“Joboy” by Diana Wynne Jones

“Puz_le” by Gregory Maguire

“After the Third Kiss” by Bruce Coville

“The War That Winter Is” by Tanith Lee

“The Dragon’s Tale” by Tamora Pierce

“Dragon Storm” by Mary Rosenblum

“The Dragaman’s Bride” by Andy Duncan

Reviewed by Carla Billinghurst

Jack Dann and Gardner Dozois have been doing this sort of thing for a loooong time. There’s a reason for that: they do it very well. And their reputation is such that they can ask the best of the best to write for them. All these stories were commissioned in 2009 for this anthology. Each story is preceded by a quick bio of the author with a list of previous work and an introduction to the story. I chose not to read these until I had finished the anthology because I prefer diving in unawares.

This is a carefully arranged selection and certainly lives up to the editors’ claim that these are stories by the “masters of fantasy.” I re-visited some authors I love and discovered some whose work I now want to explore.

The book is listed under “juvenile fiction” but the stories, on the whole, are smart, funny and don’t hesitate to dip into some serious themes. The dragons range from simple-minded devouring monsters to complex beings dealing with the issues faced by immortals everywhere. There are dragons who are forces of nature, dragons who are wily and a little too human for comfort and dragons who are unique, like the Dragaman of the final story who consorts with the devil but has a heart of gold.

These are dragons who slot into their traditional fairytale roles but always with one piece of the puzzle missing – one realisation they have to achieve, one obstacle they have to overcome. While the outcomes of the stories are not unexpected – heroes marry heroines, good triumphs and friendships endure – the nuances of how dragons and humans interact are often surprising. Dragonly nature is consistent: dragons are savage creatures, so as they gain intelligence they either become better at restraining their desire to chomp their way through humankind starting with the daughters of the upper echelons, or they develop greater cunning in putting their favourite meal on the table. Gain a dragon’s sympathy or arouse its curiosity and it will offer a scaly solution. There is cross-over, too, between dragon and human – both physical metamorphosis between the two shapes and some exploration of what a dragonish human or a humanish dragon might be like.

Any book about dragons needs to explore belief and there are stories here about the strength of beliefs and of cultural paradigms that only allow us to notice a narrow range of possibilities or to admit a limited collection of phenomena into the realm of the everyday. No matter how far we travel, as the song says, we take the weather with us.

I remember bushwalking in Australia and meeting a tiny creature, about two feet tall, walking on two legs with tiny arms extended for balance or begging. My European-raised mind offered “dragoncatdogelf ELF!” before gathering some actual evidence and labeling it “lizard.“ Then the creature shared our picnic with us! What it did that day is something I still, after twenty years in Australia, don’t include in my definition of proper lizardly behaviour – I refuse to. Lizards neither walk on their hind legs nor seek the company of humans but…this one did. The dragons in these stories are like that – each one an exception within its species, each one as novel to its own kind as it is to us.

“Dragon’s Deep” by Cecelia Holland opens the book with something gritty, romantic and a little bit sexy; a sort of Sheherazade meets Beauty and the Beast. A woman and a dragon who both have to make the difficult decision to choose what is right for each of them, not what other people think they should have.

“Vici” by Naomi Novik is the true story of how Antony met Caesar – a witty tale about a dragon out-Romaning the Ancient Romans. The dragon is a delight and the Ancient Roman environment well drawn.

After these two stories looking at humans and their relationships with dragons, the stories turn to look at the magic people develop when they associate with magical creatures. In “Bob Choi’s Last Job” by Jonathan Stroud we start to feel a little of the sadness underneath all that glory as we follow a dragon-hunter whose magical powers leave him isolated from humankind, but whose nostalgia for his lost humanity prevents him from entirely sympathising with the dragons he is suppose to hunt down and kill.

“Are You Afflicted with Dragons?” by Kage Baker is a warning to us all never to assume that a creature with apparently simple motivations cannot learn and change and, ultimately, seek revenge. Not to mention being a cautionary tale about the keepers of hardware stores. It seems to be a straightforward matter of helping a householder drive out pesky dragons, but the creatures don’t like to be outwitted.

“The Tsar’s Dragons” by Jane Yolen and Adam Stemple was probably the only story I found hard-going. It’s a complex story about revolution and the dangers of combining dragons and politics and, despite some lovely concepts, the switching points of view made it an effort to keep track of the story.

The next few stories follow a theme of dragons turning up in human worlds and how humans deal with them.

“The Dragon of Direfell” by Liz Williams just goes to prove that dragons aren’t all bad – teenage girls are much worse. Beware all you roving knight errants!

In “Oakland Dragon Blues” by Peter S. Beagle the dragon just wants to find its way home and the local policeman intervenes. This is a beautiful story with a thoughtful policeman, a properly tortured author and a real sense of the awe that ordinary people feel in the face of the extraordinary.

The very funny “Humane Killer” by Samuel Sykes and Diana Gabaldon offers up “herb” smoking Zombies, violent religions, witch-burnings and Crusaders…the cunning dragon is almost an afterthought.

“Stop!” by Garth Nix is a reminder that dragons are creatures of fire and anyone foolish enough to play with fire is liable to be burned. The dragon in this story was never, it seems, good or innocent and even as he searches for an end, has no compunction about who he takes with him.

“Ungentle Fire” by Sean Williams offers some lovely imagery and ideas about what dragons might be. Ros is sent on a quest that turns out to be not quite what he was expecting and forces him to re-evaluate his expectations of love and life.

“A Stark and Wormy Night” by Tad Williams is my stand-out favourite of this collection. Just for the language it deserves an Award of some sort. Also medals for the cutest dragon on record and the silliest-ever Draconic revenge.

“None So Blind” by Harry Turtledove is deceptively simple but stayed with me for a long time afterwards. I’ve been meaning to read Harry Turtledove for a while now and this has done nothing to discourage me. The story is a study of colonialism, of what happens when two groups of men, both believing themselves to be the “civilised” ones, meet and experience only mutual incomprehension and arrogance.

“Joboy” by Diana Wynne Jones is probably the low-point of the book which is a pity because the introductory paragraph reveals her as the author of “Howl’s Castle,” which I loved. I liked the concept in this story but felt it needed the attention of a good editor. The writing is simply not as smooth as in the other stories – it feels a little rushed and the ending is somehow a disappointment.

“Puz_le” by Gregory Maguire is a lovely look at a mother-daughter relationship mediated by a sneaky dragon. It serves, too, as a metaphor for an adolescent girl working out the puzzle of growing up. Objects that slowly reveal their magic are always fun and there is plenty of suspense watching a girl intrigued by a puzzle and wondering what will happen to her.

“After the Third Kiss” by Bruce Coville has plenty of fairytale tropes and mysteries and is a tale of transformations that go wrong. The desire for metamorphosis and then wishing it could be undone is a standard folk theme; the difference here is that the transformation is about a little more than just having nicer hair!

By this point I was starting to feel some dragon fatigue and the next story didn’t really help with that.

“The War That Winter Is” by Tanith Lee mixes the nature of the dragon with one of mankind’s oldest enemies, Winter, personified as a dragon wandering around the Arctic, freezing and starving whole villages to no apparent purpose. It’s a good story but I felt a little bit unconvinced by the idea of a caring bandit (surely the whole point of evil is that it lacks compassion?) and I wasn’t convinced by the main character’s change. I also wasn’t sure why the dragon was freezing things.

“The Dragon’s Tale” by Tamora Pierce is a lot of fun. It definitely fits into the “juvenile” category as a friendly teenaged dragon comes to grips with the responsibilities entailed in growing up with awesome powers. The strong central characters make it easy to suspend disbelief and enjoy a world where no-one is really evil and bad things are not permanent.

“Dragon Storm” by Mary Rosenblum has protective dragons, stupid villagers and evil predatory pirates. It’s a satisfying tale of friendship triumphant and evil vanquished.

Another goodie to end the book: “The Dragaman’s Bride” by Andy Duncan is a fact and fiction mystery story centering on the disappearances of young boys and girls in Virginia in the 1930s and the characters of some of the strange, hillbilly types involved in perpetrating the disappearances and the dragon living under the hill who takes matters into his own hands.

“Dragon’s Deep” by Cecelia Holland

“Dragon’s Deep” by Cecelia Holland

“Vici” by Naomi Novik

“Bob Choi’s Last Job” by Jonathan Stroud

“Are You Afflicted with Dragons?” by Kage Baker

“The Tsar’s Dragons” by Jane Yolen and Adam Stemple

“The Dragon of Direfell” by Liz Williams

“Oakland Dragon Blues” by Peter S. Beagle

“Humane Killer” by Samuel Sykes and Diana Gabaldon

“Stop!” by Garth Nix

“Ungentle Fire” by Sean Williams

“A Stark and Wormy Night” by Tad Williams

“None So Blind” by Harry Turtledove

“Joboy” by Diana Wynne Jones

“Puz_le” by Gregory Maguire

“After the Third Kiss” by Bruce Coville

“The War That Winter Is” by Tanith Lee

“The Dragon’s Tale” by Tamora Pierce

“Dragon Storm” by Mary Rosenblum

“The Dragaman’s Bride” by Andy Duncan

Reviewed by Robert E. Waters

Nineteen stories grace the pages of The Dragon Book, the latest anthology from editors Jack Dann and Gardner Dozois.

Cecelia Holland opens with “Dragon’s Deep.” Perla lives a humble life in a fishing town that’s under the boot heel of a cruel duke. His Highness has recently doubled their tax, which forces them to fish in very dangerous waters. On one such venture, a dragon sweeps out of the deep, gobbles up a few men, and takes the young Perla as his prisoner. She survives the beast’s wrath by telling it stories. Eventually she escapes and returns to her people, only to have a run-in with the dragon later as the villagers exact a little revenge on the Duke and his rapine thugs. The writing here is very good, but the story was predictable and a little bland for my tastes.

Naomi Novik is best known for her Temeraire series of dragon novels set during the Napoleonic Wars. In “Vici,” she takes her milieu back to the glory of Rome where a young scoundrel named Antonius is forced to slay a dragon for his crimes. He does the deed and discovers an egg among the beast’s loot. The egg hatches into a strong, and rather demanding, female dragon named Vincitatus. Later on, they wing off to Gaul where Antonius (aka Mark Anthony) meets for the first time a general on the fast track to power (Can you guess who he is?). In typical fashion, Novik’s writing is strong and vital, her dialogue sharp and witty. I liked the story, though it felt to me like an intro to something bigger and better. Let’s hope so, for I’d love to see dragons torching legions at the Battle of Pharsalus.

“Bob Choi’s Last Job” by Jonathan Stroud is one of the best in the book. Choi is a modern-day dragon hunter on the trail of an old and very cagey wyrm that can wear human flesh to conceal its identity. The problem with such beasts is that they like to eat people, and of course this does not sit well with the local authority. Choi has the old man cornered, but in walks the grand-daughter, and a conversation about right and wrong ensues. Should he or should he not kill them? Are humans any different than dragons in their needs and desires? Choi works the issues out in his mind and makes a decision. The ending falls a little flat for me, but Stroud’s clever setting, impeccable tone, and wonderful descriptive powers more than make up for it.

The wonderful, late Kage Baker rattles our funny-bone with “Are you Afflicted with Dragons?” The owners of a posh hotel are having trouble with a mess of dragons perched atop their roof, defecating everywhere and causing the patrons to fear for their lives. They hire an exterminator who asks for nothing in return other than to claim all the treasure in the dragons’ nests. As you might imagine, this can be quite a haul, since dragons love all things shiny and gold. But the exterminator is even cleverer: he relocates the dragons in other parts of the realm to repeat the cycle. Or perhaps too clever by half, since dragons aren’t stupid and they may catch on to his scheme and cause him great pain. It’s a good story, short and sweet.

“The Tsar’s Dragons” by Jane Yolen and Adam Stemple is really three stories set during the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, early twentieth century. Like Novik’s milieu, there are dragons: The Tsar has his, Lenin has his (which are red), and the two shall meet in bloody battle at the end (although that part plays out off-stage). Here we have a man who plots to kill Rasputin (aka The Mad Monk), and two Jewish characters with hopes of bringing positive change to their lives by throwing their support behind the Communists. Although I found the setting and twist on history quite compelling, the story seemed drawn out and the shifting back and forth between characters and third-to-first-person narratives was difficult to follow. Like Novik’s story, this one would be better served at novel length, where many of the non-dragon elements could be worked out to a more satisfying conclusion.

In Liz Williams’ “The Dragon of Direfell,” a very large and unpleasant “worm” has taken up residence in the hills near the town. Our protagonist, Lord Cygne, has arrived to bring his ample magical skills to bear at the behest of Duke Porthlois. But as he begins to figure out the best way to eradicate the beast, Cygne learns that the greatest threat may lie within the duke’s family. The first-person narrative employed by the author was appropriate for this kind of story, but the mystery that unfolded was not as clever as I was hoping for.

“Oakland Dragon Blues” by Peter S. Beagle is set in our time. A dragon mysteriously appears in the middle of a busy intersection, and Officer Guerra of the Oakland police force is given the unsavory task of removing it before too many people see it and start asking unanswerable questions. Guerra himself is confused as to why the dragon is here and how it got here. But as he convinces the beast to move, he learns that it was discarded by a local author who “wrote” the beast out of his story. Now the dragon wants to exact a little revenge on its creator for so rudely ripping it from its own world. Not a bad emotion to feel, I suppose, for a fairytale creature without a place to live, and the way in which it is dispatched at the end is rather clever, but the idea of a fictional character coming to life and inhabiting our world is nothing new.

“Humane Killer” by Diana Gabaldon and Samuel Skyes suffers from excessive length. It also contains four of the most annoying characters I’ve read in a long time. Here we have a fantasy world modeled around our own medieval Crusades. Armecia is a so-called half-breed Heathen sorceress that has trapped a demon in the body of a dead crusader named Leonard, who smokes weed to keep his rage in check. Madeline is a Scarred sister, a true warrior with a wimpy side-kick named Nitz. They are all en route to slay a dragon named Zeigfreid when they stumble upon each other and are forced to work together to bring down the beast. At first glance, the set-up seems intriguing, but the characters spend all of their time sniping at each other by throwing clever quips back and forth. For a few pages, this is okay, but after fifty, I found myself screaming, “Get on with it!” I realize that this is supposed to be comedy, but I just never got the sense that the characters really cared about their quest; their constant cracking wise just goes on and on, page after page, with no real purpose.

Garth Nix’s “Stop!” suffers from extreme brevity. Sergeant Karadjian’s team stops a strange hooded guy who’s stumbling through the desert toward a nuclear test site. When the guy refuses to stop, they open fire, but no amount of lead stays this wanderer from his appointed destination. Eventually they learn that this person is a cursed half-man half-dragon thing that’s wandered the world for centuries trying to find something powerful enough to destroy itself and lift the curse. Who says nuclear power isn’t good for something? In any event, I actually enjoyed this piece, but like I say, it’s too short. Just as it’s getting interesting, it ends.

“Ungentle Fire” by Sean Williams is a fine story. Apprentice Roslin of Geheb is on a quest to kill a dragon at the behest of his master. His apprenticeship will conclude if a) he finds the dragon, b) he kills the dragon, and c) brings back proof of the deed. He finds the dragon easily enough, and at first glance, the killing looks simple as well. But as he and the dragon have a chat, Roslin begins to question the true nature of his master’s request. Does he really want his apprentice to kill the dragon, or is this a test of his ability to think and act on his own? In addition, Roslin discovers that he may be a pawn in a game between his master and his more venerable dragon kin. Williams pieces out these complexities in excellent form, and brings the whole to a satisfying conclusion.

Tad Williams’ “A Stark and Wormy Knight” is told from the dragon’s perspective. A little dragon can’t sleep and thus asks his “Mam” for a story. She tells him the tale of his Great-Grandpap and his exploits in the time of knights. It’s a nice little story, although the dragon’s dialect can be a bit difficult to follow at times.

In “None So Blind” by Harry Turtledove, a new age has dawned on the Empire of Mussalmi, a kind of renaissance wherein the people want to confirm (or put to rest) the claims of dragons living in the mountainous southern region of the realm. So it is that Kyosti and his merry band of adventurers toil towards their destination to do just that. Along the way, they stumble upon one mythological creature after the other (vampires, unicorns, birds bigger than a man, striped cats, etc.), which leads them to believe that the mission has been fruitful regardless. Eventually, they do stumble upon a dragon-like creature, but is it the “dragon” from their myths? Or, is their desire to bring themselves out of their spiritual, intellectual, and scientific infancy blinding them to the real truth that something even more sinister and powerful is still out there? I think that’s what Turtledove is trying to say here, and if so, he succeeds.

Diana Wynne Jones follows with “JoBoy,” a story about Jonathan Patek, a doctor who mysteriously collapses one day and eventually turns into a dragon. He befriends another dragon and they investigate Patek’s strange illness. What they discover is a kind of human “leech” that’s sapping his energy. The writing here is okay, but I just didn’t find much in this story to enjoy.

“Puz_le” by Gregory MaGuire, author of the much popular Wicked series of novels, tells of Eleni and her mother trapped in a rental house as rain incessantly falls outside. So Eleni rifles around the house looking for something to do. She stumbles upon an old puzzle of a dragon and proceeds to put it together. But as she does so, the dragon seems to change, shift its pose, and look at her in strange ways. Non-plussed, she plugs on and has it nearly finished, when suddenly her mother jumps into the fray and stops her. What for, she wonders, and here the story takes an interesting turn. Is this cardboard dragon just a simple little creature begging to be re-made, or does it share a sinister secret with Eleni’s mother? It ended a little too abruptly for me, but the characters were interesting and the writing was very good.

Another stand-out is Bruce Coville’s “After the Third Kiss.” May Margret is a once-princess-turned-dragon by her treacherous stepmother. After a stint as the baddest beast in the land, she’s returned to maid status by her brother who assumes the throne after their father’s death. Under the circumstances, one might jump for joy. But May Margret can’t wipe the taste of power, blood, and fire from her mind. She didn’t realize just how much she liked being a dragon until it was gone. Now she’s conflicted: should she figure out a way to turn herself back into a dragon, or acquiesce to her brother’s demands, become a proper lady, do her duty and marry a man she does not like? It’s a difficult decision to make, especially when politics, power, and prestige are at play. Despite the fact that this is one of the longer stories, Colville’s writing is so clear, the plot so well-constructed, I didn’t mind its length and wished for more at the end.

Tanith Lee is an excellent writer, has been for decades, and continues to be so with “The War That Winter Is.” Nenkru’s band are scavengers, seeking out villages that have been attacked by the ice-dragon Ulkioket. As the saying goes: Ulkioket is Winter, and Winter is Ulkioket. But when the band discovers a frozen woman whose baby’s heart still beats true, they take him as their own. But Anlut is no ordinary boy; he’s been touched by the dragon’s icy kiss and has survived. Thus, he becomes the hero that could put an end to the beast’s reign. Not all is as it seems, however, as Lee brings the two together in (what we assume) is the final confrontation. But Lee adds a twist at the end that was quite satisfying to me, and I expect it will be for others as well. Lee’s writing is always clear and concise, lyrical and sophisticated. I liked it.

“The Dragon’s Tale” by Tamora Pierce is told from the dragon’s point of view. Kitten (“Kit” for short) is a kind of pet-cum-equal in the eyes of the people that she lives with. She’s incapable of communicating with the humans on their level, and this can cause serious problems, especially for a dragon that is clever and has lots to say. When a witch comes to town and becomes the center of ridicule for the local miscreants, Kit does her level best to befriend the witch and keep her and her newborn protected. That is about as much as I got out of this story. It was excruciatingly long for the subject, and I unfortunately couldn’t wait until it was over.

It seems that I’ve been reading a lot of Mary Rosenblum recently, and for the most part, she’s delivered every time. “Dragon Storm” is another good story, though it does not quite live up to some of her other work (e.g., “Lion Walk,” Asimov‘s, January 2009). Tahlia and her friend Kir discover a dragon egg in the churn and foam of the sea. At first, they do not think that the discovery is anything special, but when it becomes apparent that this is a sea-dragon, things get a little complicated. Sea-dragons are rare, and their bonding with a human rarer still. This makes Tahlia both very powerful and very dangerous to those around her. She becomes an asset and a liability to her people, as she struggles to come to grips with her newfound powers and her newfound friend. Rosenblum’s prose is always solid, but like other stories in this anthology, this one felt like an introduction to something larger.

And now we end with “The Dragaman’s Bride” by Andy Duncan. Set in the Virginia hill country, circa 1930, Pearleen Sunday is a witch/wizard who has stumbled upon quite a strange situation. The local sheriff and his deputy are capturing young mountain girls and getting them “fixed” so that they do not produce any more imbeciles (per some court ruling). When Ash Harrell’s daughter goes missing, all hell breaks loose. A Dragaman named Cauter Pike has lured the young Allie Harrell into his lair with promises of marriage. Our protagonist comes upon this dragon/human construct in the woods and is invited to his house for supper. Pearleen agrees with the intent of trying to rescue the misguided girl. But when she gets there, things are not as simple as she expected. I loved this story on many levels. The first-person narrative is excellent, and reminds me of some weird William Faulkner story. The cast of characters was interesting, the setting, the situation – everything worked very well, and brings a pleasant end to the anthology.