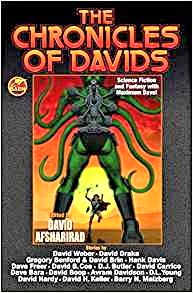

Edited by

David Afsharirad

(Baen Books, September 3, 2019, pb, 304 pp.)

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

Some while back at DragonCon, the idea behind The Chronicles of Davids came to editor David Afsharirad during a conversation with Christopher Ruicchio, associate editor at Baen Books. The pair had been struck by the realization that the company had published an unusually large number of authors named David and, at LibertyCon a few months later, the idea received the greenlight from publisher Toni Weisskopf. Thus, the search began to compile a lively book of science fiction and fantasy written by authors who shared the name David. Published on September 3, 2019, The Chronicles of Davids features ten original stories and five reprints, all falling somewhere within the science fiction and fantasy genres. The reprints have not been reviewed here.

“The Savage” by David Drake

Dr. Howe of the Republic of Cinnabar needs hunters to collect specimens on the planet Api. Expecting three men, he gets a surprise when a woman named Joss arrives asking to be one of his hunters. On Api, it’s taboo for women to hunt but Joss had left the planet after being raped at 15, only to join one of the top military special forces in the Alliance. He decides to hire her, upsetting the local leaders.

While I enjoyed Drake’s story, it left me with a lot of questions about Api and its people. Why do the Republic of Cinnabar citizens call them apes? What makes them different? There’s a hint that there’s more behind that nomenclature than simply a nickname based on the planet. Dr. Howe says he understands why they were called that but it’s never explained. That one detail aside, it is a great read. I did not see the ending coming at all. I kept expecting the conflict to rise from the tensions between Joss and the male hunters but it never does. It comes instead from a very unexpected source which is what made it fun.

“The Seven Nipples of Molly Kitchen” by D.J. Butler

Deep in a mine shaft in Utah, Hiram is following Rose Callaghan to see a child’s body that she claims to have found there. As they trek further in, Hiram’s fears are confirmed when it becomes clear they’re not alone in the darkness.

The title that Butler chose for his story is quite provocative and piqued my curiosity. There are a few editing mistakes throughout (some more glaring than others, such as when Rose’s “face curls into a fist”) but, overall, it’s a very entertaining bit of horror.

“DeMille and Me” by D.L. Young

Max has been working in the filmmaking business for more than twenty years, leaving a long trail of failed films in his wake. After a six-year dry spell with no work, acclaimed AI filmmaker DeMille asks him to direct his next film but, much like Max’s personal life, the project is afflicted by a series of problems, forcing him to consider a radical career move.

Young’s story was interesting, to say the least. It captures quite well what I imagine it would be like to fail repeatedly in Hollywood as a director, or really in anything about which one feels passionately. The moniker “one-hit wonder” is something that nobody, in any field, wants associated with their reputation, and this makes Max a sympathetic character. He believes in his vision so deeply and yet others seem to be unwilling or unable to appreciate what he does. I’m certain that more than a few of us can relate to that feeling.

“A Servant of the Protector” by David Hardy

Servant Josef, a willing half-cybernetic soldier of the Protectorate, has been sent to a colonial planet named Port Farewell to help the colonists there fight against an alien incursion. Upon arrival, he meets the beautiful and charming Elizabetta, the Coregent’s niece. When a surprise attack by the mantids results in many colonists, including Elizabetta, being taken hostage, it’s up to Josef to return them home.

I’ve got to admit that Hardy’s story was not my cup of tea in general. It would have benefited from a little more editing, especially since there seem to be several instances where a particular word is heavily used over and over in a small bit of text. For example, the word “plasma” is unnecessarily repeated over and over in the first fight scene. There is no need to keep referring to both the weapons and their ammunition by that description. We already know they’re plasma cannons—we don’t need to know that plasma cannons shoot plasma bolts. The simple word “bolts” is more than enough description of a plasma cannon’s ammunition.

The description of the drakes is also confusing. In the first fight, the drakes have no problem keeping up with a spaceship traveling at over 300 miles per second (or roughly 1,000,000 miles per hour). In the skirmish on the planet, though, they can’t keep up with an aircar moving at a far slower speed. How, then, did they catch up with the spaceship?

The biggest issue, though, is that Josef’s voice is inconsistent. When he’s introduced, his way of speaking and his mannerisms are very formal, almost to the point that he seems to be a bit robotic. Once he sets off to rescue Elizabetta and the other captives, he suddenly becomes casual and informal.

“As It Began” by Dave Bara

In the distant future, mankind has colonized the stars. But this comes with a heavy price—stagnation of the gene pool on the various worlds. And so the Chronicles demand that princes and princesses travel the universe to these planets in order to breathe new life into the human race. Dowager Empress Maren of the Maroon Court was betrothed and wedded to once such prince. They shared a brief romance, long enough to confirm that she had conceived a child before leaving her to continue his sacred duty of copulating with women on other worlds. Devastated, Maren never wed another prince and thus bore only one child, Elissa. Now an old woman, she and her daughter must watch as the last of her great-grandchildren board a space shuttle to follow in Bespoe’s footsteps and keep the human race alive.

Bara’s story is a truly bittersweet tale of love and loss, of longing and regret. Although I’d liked to have known a little more about what the Chronicles were and how they came to be necessary, it was quite a good, but very sad, read.

“Four Days” by David Carrico

Kevan, a wandering warrior, finds himself working for Baron Leofric in the defense of Rova and Nikoras, two towns situated on opposite banks of the Eigil River. In the distance, a horde of Mydhiote tribesmen approach. Their reputation for leaving no survivors has sent most of the residents of Rova fleeing for shelter in Nikoras while the horde ransacks the town. Little can stop the horde’s onslaught of destruction but Kevan has an idea, one that means he has to survive four days of virtually non-stop duels with the horde’s champions.

Carrico’s story is a very good read and one I definitely recommend. The dialogue is a bit odd here and there and I encountered one or two editing mistakes but it’s otherwise well-written, fast-paced, and holds your attention to the end.

“The Tyranny of Distance” by Dave Freer

In a world where everything is controlled by AI, humans are considered expendable resources and forced into slavery. Every aspect of life is both controlled by, and the costs incurred charged by, the AI’s through the network. Jon Ribble has lived under this tyranny his entire life and now he’s about to graduate with an enormous amount of debt. Unfortunately, his hopes of being selected to work in the sewers, where connection to the network was reported to be unreliable and escape possible, were dashed when he’s sent to Gate 7 with other members of his graduating class. He’s terrified and understandably so, since Gate 7 is a well-known one-way trip to outer space. The only question now is whether this leads to death or freedom.

Although Freer’s tale is most certainly science fiction, it also bears hallmarks of the horrific, as well. Much like the film The Matrix, the machines humans built to make their lives easier end up being their ultimate downfall. The difference between them, though, is that, in Freer’s world, the takeover is more insidious and humans have willingly given up every aspect of their lives to the AI’s control. It’s quite a terrifying prospect to consider. Freer’s humans are little more than chattel property to be bred, injected with infantilizing medication to keep them docile, and used for any undesirable purposes, including those that are sure to end in their death. Still, the story isn’t without its share of hope, as the ending demonstrates. This is most certainly a story I would recommend reading.

“Lyman Gilmore Jr.’s Impossible Dream” by David Boop

Chuck’s genius inventor brother, Lyman, has a vision. It involves a town somewhere in Arizona being attacked by flying things far more agile than the monoplane he’d been trying to build and a man with glowing eyes who radiates pure evil. When they near their destination, the monoplane in tow, terrified townsfolk race past them, hell-bent on escaping whatever is terrorizing the town of Drowned Horse. Now, just a mile from town, they are confronted with a sight they aren’t quite expecting—dragons. But that’s not all they’ll find in the cursed town of Drowned Horse.

My first impression of Boop’s story is that it could use a bit more editing and better research. To start with, some of the sentence structures are either incomplete or simply badly written and full of typos. For example, there’s one sentence that reads “When I phrased a question like that so he’d kindly dumb down the answer.” Unfortunately, that’s not a complete sentence; it’s either missing the rest of the thought or it needs to be rewritten so it is complete, especially since it’s not a statement made to answer a question.

As written, the part about Noqi is also muddled in its logic and, generally speaking, is somewhat inaccurate. While some revisionism is expected in historical fantasy (or, more specifically, gunpowder fantasy) I’m not certain it’s appropriate for the genre to mix cultural concepts the way that Boop has done. First, gaming has historically been a part of the various American Indian cultures but gambling has not—and the two concepts are not the same, even though modern usage of the word “gaming” conflates one with the other. These games were not usually played to win but instead served a more ceremonial purpose. Therefore, the existence of a gambling deity intent on stealing souls at any cost is highly unlikely.

Second, if Noqi is an Apache deity, then one would expect the other entities in his control to follow suit. Quetzalcoatl is a Mesoamerican deity worshipped by the Inca, Maya, and Aztec peoples, as well as a few other tribes in North America. The name is Nahuatl and belongs to the Uto-Aztecan language family. The Apache language belongs to the Athapascan language family and shares ties to northern tribes like those in the Canadian Yukon. While trade was taking place between tribes between tribes in North and South America (for example, copper from Michigan has been found in South American archaeological sites just like feathers from Amazonian birds have been found in New Mexican sites), the two languages are not interchangeable and neither are the cultures of either group. And while it’s true that the Apache were aware of Quetzalcoatl as a deity, as evidenced by his role in a few of their creation myths, it doesn’t seem plausible that they would assign the feathered serpent god’s name to a featherless dragon-like creature serving another Apache god (for a variety of reasons).

All of that said, though, it was quite a novel story. And while I don’t see an ancient god being frightened of, and certainly not defeated by, a souped-up monoplane, I quite like the idea of a cursed town beset by all manner of dark horrors, from undead to dragons.

“Too Many Gods” by Hank Davis

Far in the future, humans are at war with insect-like aliens in the outer reaches of space. The god Ra has sent Bast on a mission to find out why the humans, who are much better equipped, are losing to the weaker aggressors. Sneaking onto the starship and hoping she won’t be outed as a non-human, she discovers that someone has put a compulsion spell on the feline agents she’s placed aboard the ship. With the war god Ares on the ship with her, the two of them realize yet another god is helping the alien invaders and they have to figure out who and why before it’s too late.

There are a few typos, such as a few extraneous commas or missing spaces between words here and there. Visually speaking, the way the text is broken up emphasizes Bast as a scatterbrained goddess but this also increases the negative aspects of her and the other characters. She’s essentially a “super-annoying-friend-of-a-friend-who-won’t-shut-up-and-rarely-gets-invited-to-parties” stereotype of a character, which is so overwhelming that it’s incredibly off-putting. It doesn’t come across as cute or endearing, and it certainly doesn’t make her seem like the powerful protector goddess or warrior that she’s supposed to be. Instead, she’s a featherbrained, self-absorbed, spoiled pre-teen child. And Ares isn’t any better. Top this off with the limitations Davis has placed on his so-called gods and, overall, Bast and her ilk just aren’t very impressive or even really all that godlike. The dialogue doesn’t help matters either, often feeling forced and contrived. Overall, this story is rambling and long-winded, lacking relatable or even tolerable characters.

“An Epilogue: The House of David” by Barry N. Malzberg

A group of soldiers is put into military training using the Slammer technique. Their identities are ripped away, each replaced with the name David. Over time, the Davids become a homogeneous group of fighters in an endless war.

As someone who is not familiar with David Drake’s work, Malzberg’s story took a bit of legwork before I could write a review on it. Don’t get me wrong; it’s an okay story—not great but not bad, either. It’s just that without knowing a few things in advance, some readers like myself may not understand why it was included. The first is the mistaken belief under which he wrote it, which was that The Chronicles of Davids was a tribute to David Drake’s body of work—it is decidedly not. The second is that David Drake is well-known for military science fiction. Without those two pieces of information, the story seems somewhat abstract and brief, lacking a protagonist with which one can relate. Next, one needs to understand that the “Slammers” mentioned in the story refers to a mercenary tank regiment called Hammer’s Slammers that is the focus of a collection of Drake’s military science fiction.

The final key lies in a single concept mentioned in the text, that being the ethics of closure. Again, I had to do a bit of research to gain some insight into this but, to the best of my understanding and in a very tiny nutshell, ethics of closure refers to the moral consciousness of bureaucracy and the codification of conduct in which a group is reduced to a single identity determined by a decision-making elite. It is forced upon the members and reinforced frequently using various methods, and strips members of the group of their right to make decisions for themselves.

This last piece of the puzzle seems especially vital for coming to a full understanding of Malzberg’s point. Unfortunately, that message is lost on me simply because I have not read anything by David Drake, barring the first story in this anthology. What I can say is that identity is important because, without it, we are easy to control. Without it, we lose the ability to think for ourselves and make decisions, perhaps acting only if those around us do the same, even if those actions are horrifying. To me, this is what the story seems to demonstrate. But I cannot, however, comment on how Malzberg’s story relates to Hammer’s Slammers or how it fits in with or compares to the remainder of David Drake’s body of work.

The Chronicles of Davids

The Chronicles of Davids