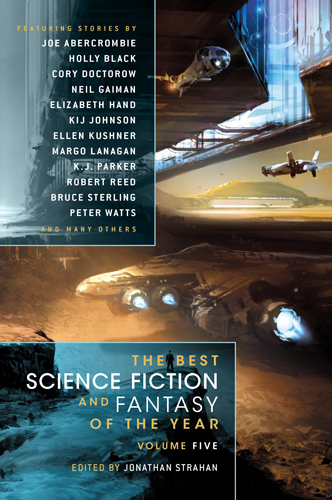

The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume 5

The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume 5

Edited by Jonathan Strahan

(Night Shade Books, 2011)

“Elegy for a Young Elk” by Hannu Rajaniemi

“The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains” by Neil Gaiman

“Seven Sexy Cowboy Robots” by Sandra McDonald

“The Spy Who Never Grew Up” by Sarah Rees Brennan

“The Aarne-Thompson Classification Review” by Holly Black

“Under the Moons of Venus” by Damien Broderick

“The Fool Jobs” by Joe Abercrombie

“Alone” by Robert Reed

“Names for Water” by Kij Johnson

“Fair Ladies” by Theodora Goss

“Plus or Minus” by James P Kelly

“The Man With the Knifes” Ellen Kushner

“The Jammie Dodgers and the Adventure of the Leicester Square Screening” by Cory Doctorow

“The Maiden Flight of McAuley’s Bellerophon” by Elizabeth Hand

“The Miracle Aquilina” by Margo Lanagan

“The Taste of the Night” by Pat Cadigan

“The Exterminator’s Want Ad” by Bruce Sterling

“Map of Seventeen” by Christopher Barzak

“The Naturalist” by Maureen McHugh

“Sins of the Father” by Sara Genge

“The Sultan of the Clouds” by Geoffrey A Landis

“Iteration” by John Kessel

“The Care and Feeding of Your Baby Killer Unicorn” by Diana Peterfreund

“The Night Train” by Lavie Tidhar

“Still Life (A Sexagesimal Fairy Tale)” by Ian Tregillis

“Amor Vincit Omnia” by K.J. Parker

“The Things” by Peter Watts

“The Zeppelin Conductor’s Society Annual Gentleman’s Ball” by Genevieve Valentine

“The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window” by Rachel Swirsky

Reviewed by Sarah Joynt-Borger

The science fiction and fantasy genres have seen a reimagining in recent years, both genres broadening their borders, new writers adding voices and themes to revitalize both fields. The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume 5, edited by Jonathan Strahan, attempts to illustrate these widening definitions of the genres, with various levels of success. More often than not, the stories re-tread old themes and archetypes, bringing little that is new or different to their varying genres. Most of them, while entertaining, hardly seem to fit the ‘best of’ in the anthology’s title.

The twenty-nine short stories in this volume have all been printed before, in a variety of different types of publications, both print and electronic, and they range from classic science fiction to stories of faeries and knights—there’s even a zombie or two.

Hannu Rajaniemi’s “Elegy for a Young Elk” is a well–written science fiction story of a future, annihilated Earth and the few humans who remain behind. Dealing with the themes of family and debts, “Young Elk” is pleasant but offers nothing new or ground-breaking, though the idea of a singularity controlling whole cities is thought-provoking.

“The Truth is a Cave in the Black Mountains” by Neil Gaiman is a dark fantasy morality tale on family and trust—and the search for the ‘Truth.’ Thoroughly enjoyable, if somewhat predictable in places, the story moves quickly and the characters compel interest in their lives and choices.

In her new take on the ‘when-robots-are-more-human-than-humans’ story, Sandra McDonald’s “Seven Sexy Cowboy Boots” is slightly scandalous, slightly heart-tugging and slightly trite. A pleasant enough science fiction tale, it re-covers old ground well without adding anything truly new.

“The Spy Who Never Grew Up” by Sarah Rees Brennan is another take on the Peter Pan what-if world. In this case, what-if Peter Pan worked as a spy for the Crown? Attempts at humor mostly fall flat, though the portrayal of Peter Pan as a spy with no scruples was blood-chilling.

Holly Black’s “The Aarne-Thompson Classification Revue” is a story that falls into the recent wave of chick-lit thinly veiled as science fiction/fantasy/horror (see Kelley Armstrong’s “Bitten” series and others of that ilk). While entertaining enough, the girl-power through accepting one’s supernatural otherness theme is rapidly losing its originality.

“Under the Moons of Venus” by Damien Broderick is a strong piece of speculative science fiction, its characters strongly drawn and their plight compelling; but its denouement comes to rapidly, and feels slightly forced.

Joe Abercrombie’s “The Fool Jobs” is a stock group-of-hardened-bad-guys-with-hearts-of-gold story, with quick pacing and well crafted, if expected, characters, though it feels like a chapter in a larger novel rather than a stand-alone short story.

One of the best stories in the anthology, “Alone” by Robert Reed, is a grand, large canvas hard science fiction piece. Though at times it moves slowly and its reveal can feel ponderous, the overall scope and arch of the story are captivating.

In “Names For Water,” Kij Johnson writes a brief, vignette-type look into a young girl’s rush to class, and a cell phone call that gives her a glimpse into the future. More of a treatise on cell phone reception than anything else, the piece is just a glimpse into the girl’s life more than a fully told story.

Theodora Goss’ “Fair Ladies” is an absorbing, complex, captivating fantasy story about the risks and sacrifices love demands. Well written, it moves quickly and without sacrificing dialogue or characterization. The world of man and faeries is real and the risks are high.

“Plus or Minus” by James Patrick Kelly, is standard science fiction fair about trouble aboard a mining/transport ship. Well written, fast-paced with fairly stock but intriguing characters, Mr. Kelly takes his story through the normal science fiction paces.

Ellen Kushner writes a decent, if somewhat simplistic story about love and loss and sexuality. “The Man With the Knifes” never really hits its stride however, and the ending seems too easy and too fast.

“The Jammie Dodgers and the Adventure of the Leicester Square Screening,” by Cory Doctorow, is a fun steampunk romp through a London we almost know. Amusing, fast paced; with compelling characters—if a little heavy on the techno-babble—“Jammie Dodgers” is a light, pleasing story designed to entertain.

Award-winning writer Elizabeth Hand returns to the territory she visited in “Last Summer at Mars Hill” with her short story “The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s Bellerophon,” as friends of a dying woman attempt to deal with her death, as well as find a way to celebrate her life. Sometimes trite, the story never really takes off enough to grab a reader’s attention, though the author’s obvious talent makes it a pleasant read.

In “The Miracle Aquilina” Margo Lanagan explores themes of femininity in a male-dominated world, and the cost of remaining true to one’s beliefs—and the sacrifices people make for the sake of said beliefs. Well-written, the story is compelling, the characters interesting and well-drawn and the final betrayal stunning.

Pat Cadigan’s “The Taste of Night” is a strong, speculative fiction piece about first contact with an alien civilization. Creepy and disturbing in a compelling way, “Night” is an intriguing, well-written what-if tale that leaves the reader thinking.

“The Exterminator’s Want Ad” by Bruce Sterling is an engrossing social commentary on what happens when society begins to view its dispossessed citizens as entertainment. While the basic story—prisoners used as entertainment—has been done before, the angry, informal first person narration and the casually vicious details dropped in make for a goose-bump raising morality tale.

Christopher Barzak attempts to use fantasy-as-metaphor-for-acceptance in his fantasy short, “Map of Seventeen” but the story misses its mark. Filled with good intentions and touting tolerance, the writing sometimes becomes preachy and trite, and the reveal at the end lessens the potency of the LGBT-acceptance message of the work.

“The Naturalist” by Maureen McHugh, crosses over into the horror genre—with zombies! A good, old-fashioned zombie story that hits all the major ‘zombie’ plot points but does it with verve and a sense of fun.

In the next story, Sara Genge’s “Sins of the Father,” is another look at family and forgiveness, between genetically engineered mer-people who now control the resources of the world, and the men they subjugate. The premise is interesting, but the writing is clunky, and a lot of the exposition dumped into the story at the end, rushing the ending and making the characters involved, is hard to connect with.

Geoffrey A. Landis’ “The Sultan of the Clouds” is a solid science fiction story in a world with believable sociological changes in a future society shaped by space exploration backed by greed and profit. The plot moves quickly and establishes the world and the characters, and exposition is handled well—always a great feat in a work with this much backstory.

“Iteration” by John Kessel is a lovely little story about being able to change one thing…and the changes that spiral from that. The magical genie-in-a-bottle as a google-maps type website idea is amusing and captivating, while the ending has a haunting tone of warning.

Diana Peterfreund writes an effective, modern fantasy story of a young girl finding her own self and sense of independence (along with the power to train and command unicorns) in “The Care and Feeding of Your Baby Killer Unicorn”.

“The Night Train” by Lavie Tidhar is a steampunk-ish, vaguely William Gibson’s Neuromancer-world story. Well told, with a large amount of information delicately given as the plot propels the story forward, it negotiates familiar territory while giving the work its own gloss.

Ian Tregillis’ “Still Life (A Sexagesimal Fairy Tale)” is one of the best in the anthology, a tender, thought-provoking story about a land without time…and love. And one woman’s sacrifices for both.

“Amor Vincit Omnia” by K.J. Parker is a solid fantasy with excellent details and examples of ‘working’ magic, with an intriguing concept and characters. Well-paced and plotted, though the magic-terminology exposition gets a little heavy.

In “The Things,” Peter Watts’ retells John Carpenter’s The Thing from the point of view of the aliens. An indictment of humanity, the story soon becomes trite with little attempt at any grey areas.

“The Zeppelin Conductors’ Society Annual Gentleman’s Ball” by Genevieve Valentine is a steampunk, alternative-history vignette about the men who work in the gas-filled zeppelins, whose physiology changes due to the weightlessness in the balloons. More of a slice of life, with unconnected events seeming to happen randomly, then a full short story, it is nonetheless well-written and the world is interesting.

The final story in the anthology, Rachel Swirsky’s “The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers,” is a strong ending to the book, an intriguing, involving, millennium-spanning story of gender bias, magic, love and betrayal.

The anthology, rather than being a true ‘best of’ is more of a collection of ‘perfectly fine’ stories. A good read, but nothing ground-breaking or earth-shattering.