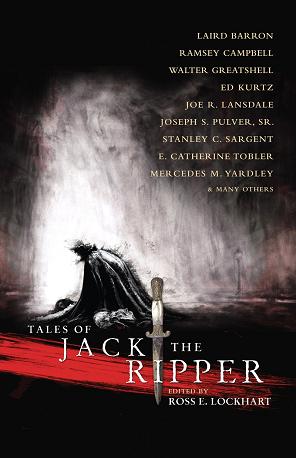

Edited by Ross E. Lockhart

(A Worde Horde Book, August, 2013, 245 pp.)

Reviewed by Lillian Csernica

“Whitechapel Autumn, 1888” by Ann K. Schwader

A Shakespearean sonnet constructed with a beauty of scansion fit to please the heart of the most demanding Professor of English Literature. The imagery is haunting, as well it might be given the subject matter. Each word is chosen with exquisite attention to connotation and denotation, combining to create a resonance capped nicely by the bitter irony of the final line.

“A Host of Shadows” by Alan M. Clark and Gary A. Braunbeck

While lying on his deathbed, Howard Faber reflects on his life as a brilliant physician. His career has included many medical miracles. Have they been enough, though? Has Faber done enough to atone for what happened in Whitechapel? Faber’s best friend and attending physician, William Springer, does his best to watch over Faber and see that he receives the care a man of his greatness deserves. Faber’s declining health has locked him up inside his body more effectively than putting that body in a jail cell. All he can do is think while he suffers the presence of his sister Estell, the visits of the marriage-minded Miss Lumbly, and his own anxieties about his son Wayne. Living in the shadow of his father’s greatness has taken a terrible toll on Wayne, leaving him warped and alcoholic and in fine shape to carry on the family taint.

The immediacy of the viewpoint makes this story both terrifying and heartbreaking. Is Faber’s condition ironic justice or tragic punishment? His grief over Wayne’s true inheritance makes Faber more human and a figure of pathos. He knows that after he’s gone somebody will find his secret stash of trophies. People will need a scapegoat, and there’s poor Wayne, about to find out his role model for all things great and noble was really a psychopathic serial killer. Miss Lumbly also serves to illuminate another aspect of Faber’s character. A faded flower, widowed yet still a social climber, she wants to hitch her wagon to Faber’s star. She doesn’t want the man, she simply wants what she can get out of him, much like the whores of Whitechapel.

Faber’s mind shifts between past and present, between Jack and Faber, between what really happened and what people in the present want to believe. The forward motion of the story is supported by the clarity of the exposition and the subtle cues that anchor the reader in the right time and place. The intricacy of this story’s construction is a real achievement. I can foresee this story enjoying a long future in Anthology Heaven.

“Jack’s Little Friend” by Ramsey Campbell

Master of horror Ramsey Campbell uses the second person narrative to tell this creepy little gem. Is the voice that tells the story the voice of the poor fellow who finds the metal box with four dates scraped on the lid, dates that correspond exactly to the murders of Jack the Ripper? Or is the voice somehow related to what was, or is, or will be inside the metal box? Ambiguity and uncertainty are the key elements here, used in just the right amounts to provoke the steadily growing suspense and dread that the reader can be sure to encounter in Campbell’s work. The main character begins to theorize about what Jack might have been searching for inside the bodies of the women he butchered. Endless contemplation leads to a need for more practical research, culminating in a climax both shocking and bizarre. Then comes the last line, where Campbell delivers the coup de grace.

“Abandon All Flesh” by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Julia has a fixation for the figure of Jack the Ripper in the museum where her father works. She stares at him and tries on his hat and speculates about what really happened on the bed that is part of the scene where Jack murdered Mary Kelly. Julia also has a fascination for Aztec culture, its sacrifices and the cosmology behind them. With no healthy role models, a crowded home full of dysfunctional family, and a romantic and/or sexual attachment to a serial killer, Julia has all the makings of a sociopath. It takes no great leap of imagination to know the union of her two interests mean trouble when Julia finally decides to start returning the attentions of David, her study partner. The actual writing here is often subtle and beautiful, suggestive of multiple levels of meaning. I have to say Julia’s bedtime fantasies about Jack the Ripper and his knife are so blatantly Freudian they’re almost funny. The end of the story comes as no surprise, although it does make clever use of a twist on a classic fairytale ending.

“God of the Razor” by Joe R. Lansdale

An antiques dealer goes to an old, abandoned house hoping to find some forgotten treasures. Instead he finds a basement full of water, rats, and other far less pleasant things. The occupant of the house is some distant cousin of Jason from all those Halloween movies. What I enjoyed most about this story was the God himself, a nasty cross between Baron Samedi, Pinhead, and your own personal worst nightmare. Some parts are creepy, some parts are exciting, some parts are both. Still, I am compelled by my responsibilities as a reviewer to say that once the protagonist starts down the basement steps, the rest of the story is a done deal. I did not get the impression this was meant to be a parody or satire or any deliberate mockery of horror’s oldest tricks. Jack the Ripper himself has very little to do with the story. There’s plenty of good writing here, but the story itself is familiar and disappointing.

“The Butcher, the Baker, the Candle-stick Maker” by Ennis Drake

Another second person narrative, told with brutal attention to detail and such intense immediacy it was difficult to read all in one go. The protagonist is a man of contemporary times who is driven to recreate Jack the Ripper’s crimes. The way the story is written combined with the way the text is laid out on the page combine to great effect. In the finest tradition of modern serial killers, the protagonist keeps clippings of the news coverage concerning his murders. He can tell what details the police have released and which ones they’re holding back, adding to his sense of power and control.

What makes this story most effective is not the madness of the protagonist or the gory details of his murders. It’s the way the story points out the apathy, the callousness that makes it possible for people to commit random acts of violence. The title is meant to demonstrate how the protagonist could be anyone. The guy who delivers pizzas, the CEO of a corporation, our kids’ math teacher. We just don’t know, and we’ll never see it coming. For me, this story best embodies the enigma of Jack the Ripper and his crimes.

“Ripping” by Walter Greatshell

Told in bare dialogue, this twisted little tale follows the meeting of a small-time film director looking to audition the dancer he’s just met in some late-night bar. She’s clever and witty, and he seems to be all he claims he is. Once they reach his basement-cum-studio, matters take some very strange turns. When it comes to strong characterization, lean and meaningful dialogue, and the involvement of the reader’s imagination, I couldn’t ask for more. Mr. Greatshell shows not just talent but an impressive amount of real skill in pitching some wicked narrative curve balls.

“Something About Dr. Tumblety” by Patrick Tumblety

Poor Dr. Tumblety. He’s anxious to land a good recommendation for an internship from Dr. Elizabeth Carmine, known as “Dr. Death” because of her chilly demeanor. Dr. Tumblety tries so hard, but life is just one pratfall after another. Adding to the good doctor’s dejection is the discovery that he is the descendent of Francis Tumblety, also a medical doctor and one of the prime suspects for Jack the Ripper’s murders. In the tradition of reading about symptoms and then suddenly thinking you have them, Dr. Tumblety starts to wonder if he has inherited something terrible. All the men in his family seem cursed. Maybe Dr. Francis is where it all began. I like this story a lot because I like Dr. Tumblety. I like the trials he goes through and the choices he has to make. The tone of this story is lighter than most, except where it’s not. That’s done very well. As for that critical element, the ending, I was quite satisfied. Here’s an added bonus: Patrick Tumblety, the author, is a real person, and Francis Tumblety really is his ancestor. Good for you, Mr. Tumblety. I congratulate you on making such good use of your own family history!

“The Truffle Pig” by T.E. Grau

The steampunk fans get plenty of thrills from Jack the Ripper, so I was happy to see this high class dose of science fiction in the mix. The plot revolves around the answer to the eternal question of why Jack the Ripper killed those five women in such a grisly manner. Who the main character is and what that person’s real purpose might be will keep you guessing right up to the end. The use of language in this narrative is poetic, vibrant, and surprising. The precision of the word choice put me in mind of a mosaic with each tile deliberate and unique. Strong tension, a lot of information properly dramatized, and a great ending.

“Ripperology” by Orrin Grey

Two single. lonely men who are both amateur scholars of serial killer lore meet at a convention and develop what passes for a friendship. The older of the two men has a collection of memorabilia from some of the most famous serial killers, including Jack the Ripper himself. This gets rather strange even by the younger man’s standards. Worse it yet to come. Not a lot happens in this story, and what does happen carries a tone of implicit meaning that is too subtle to go in a definite direction. Given that, the ending left me confused and unsatisfied.

“Hell Broke Loose” by Ed Kurtz

The story opens in Texas during the Christmas season of 1885. Blake Prentiss, brought low by women and drink, mopes around pining for the love of his life who is forever beyond his reach. That’s most of the plot, and a long plot it is, going on and on like a bad Country & Western song that just won’t end. Blake has some kind of psychotic break and ends up in London, just in time for the start of the Ripper murders. This story is exhaustive to read thanks to being excessively complex. By the time the ending finally arrives, it is both predictable and anticlimactic.

“Where Have You Been All My Life?” by Edward Morris

A man wakes up in a strange room beside a prostitute he doesn’t remember. Fortunately for him, the prostitute is a fountain of information, supplying all the details about him being English, how he’s now in Portland, Oregon, and answering all the other questions the reader might have. The time is four or five years after the Jack the Ripper murders. Odd bits of the man’s fragmented memory start piecing themselves together in a manner that makes the prostitute’s odds for long term employment very unlikely. The story is dedicated to Harlan Ellison, which implies that the memories are in fact the manipulations of beings similar to the ones who controlled Jack in Ellison’s “The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World.” The story lacks tension thanks to the prostitute’s ongoing info dumps. The main character lacks any individuality, which may be the point but comes across more as a sin of omission. The ending is a foregone conclusion almost from the first line.

“Juliette’s New Toy” by Joseph S. Pulver, Sr.

This story is dedicated to both Ellison and Robert Bloch, whose story “A Toy for Juliette” appeared alongside Ellison’s story in the anthology Dangerous Visions. Juliette is on the loose again. Has she switched places with Ellison’s Jack? Has she merged with the blade of Bloch’s Jack? I have no idea. There isn’t a plot here so much as the suggestions of events and Juliette’s deliberate enjoyment of the ambiguity. Or I could be totally wrong about that. The writing is vivid and contains some imagery and turns of phrase which ambush the mind with their bizarre juxtapositions. Strip that away and you have a smug, narcissistic sadist out for a night’s bloody gratification.

“Villain, By Necessity” by Pete Rawlik

Thomas Newcomen is a veteran of Afghanistan. As the story opens, we find him in disgrace at Scotland Yard for his failure to resolve a rather startling case. Having taken early retirement, Mr. Newcomen renews his taste for opium and ruins what passes for his life. Lucky for him, he’s about to meet with a sudden career opportunity, presented to him by a startling and delightful pair of unwilling allies. The writing style here reminds me of all that’s best in the original Sherlock Holmes stories. The depth of characterization and the precise back story make Newcomen a sympathetic main character and a man to be respected, regardless of his lapses. I enjoyed a relatively rare experience in the reviewer’s life: I didn’t want the story to end. Give us more Newcomen stories, Mr. Rawlik! You’ll find an eager audience!

“When Means Just Defy the End” by Stanley C. Sargent

Constable Edmund Setlock and Chief Commissioner Sir Charles Warren discover the secret of Jack the Ripper’s true identity. What’s more, they are forced to accept the reasons why that secret must be kept. The premise here works well enough. The story is burdened with a lengthy and detailed back story for the man who is Jack the Ripper. While it explains his psychosis and his motivations, the pace drags and there’s no real tension. The subject of child abuse is a central factor. I’ll be the first to acknowledge the horrible living conditions of the poor in 1880s London, but child abuse is a theme seen all too often in horror fiction. As a result, that content is not really horrifying and lacks emotional impact. The elements of a good story are all here, there’s just too much middle.

“A Pretty for Polly” by Mercedes Yardley

A British gentleman of quality has a young daughter whom he loves. She comes in every evening to say goodnight, little knowing that Daddy is busy writing the mocking letters Jack the Ripper sends to Scotland Yard. The psychology of the gentleman is well done. As the story progresses, he begins to lose track of where he ends and the killer in him begins. This is reminiscent of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. There are a few nasty moments in the story, planted with a wicked sense of timing and subtlety. The ending lacks conclusiveness. Will the downward spiral continue? Is the gentleman becoming a danger to his little girl? A little more clarity there would have given the implication ending the focus it needs.

“Termination Dust” by Laird Barron

In the sole apartment building of a tiny Alaskan town a holiday party turns into a disaster. The host spikes the punch with LSD, residents fall prey to a mystery killer, there are random cameos by Elvis and Michael Jackson, and the building catches fire. Jack the Ripper is mentioned a few times in the course of the story, but some other unnamed evil is abroad. This is another long story in which a lot happens, but the way the narrative bounces around makes it even harder to follow than “Hell Broke Loose.” Unreliable narrators and multiple viewpoints combined with a nonlinear plot make for laborious reading.

“Once November” by E. Catherine Tobler

The five ghosts of Jack the Ripper’s victims haunt the woman who lent her room to Mary Kelly on that fateful evening. The woman is driven by survivor guilt. This story starts off well. The idea that the five victims are trapped in each other’s company because of their common experience is an idea with a lot of potential. I was curious to see what the main character would choose to do about her guilt and the other forces tormenting her. Her choice for absolution is weak, predictable, and unsatisfying.

“Silver Kisses” by Ann K. Schwader

Another sonnet, rendered with precision and skill and an artfulness that makes this old-fashioned girl weep with appreciation. (I’m a member of the school of thought that believes poetry should rhyme.) This is a love letter from Jack the Ripper to Mary Jane Kelly, clever and poignant and creepy all at once. I applaud Ross Lockhart for opening and closing this anthology with Ms. Schwader’s works. Her sonnets set the haunting mood, and leave it lingering in one’s mind.

Ross Lockhart has done well, selecting a broad variety of stories. There’s a good mixture of viewpoints, male and female, villain and victim, living and dead. Readers interested in Jack the Ripper will love this anthology. Horror fans in general should be quite pleased.