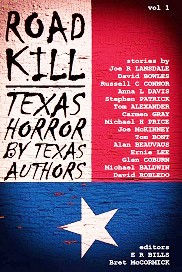

Road Kill: Texas Horror by Texas Authors

Road Kill: Texas Horror by Texas Authors

edited by

E. R. Bills & Bret McCormick

(Eakin Press, Oct. 2016, 227 pp.)

Reviewed by Brandon Nolta

For better or worse, Texas has a lot of connotations in America. As a geographical area, it’s vast, second only to Alaska. As a cultural force, Texas is equally as large; whether it’s football, cowboys, textbooks, or nighttime soaps, Texas plays into American cultural life with innumerable effects. It’s almost mythical, which makes it seem like a perfect setting for horror and supernatural literature. The collection of stories that E. R. Bills and Bret McCormick have put together under that aegis illustrates that idea, but with mixed results.

The major issue with this collection is that while most of the stories are interesting, and a few are extremely clever, almost none of them are particularly scary in any way. Perhaps the idea of Texas being the uniting theme in this collection was too broad; the stories range from ghost tales to Lovecraftian monster shows, but there’s no real sense of cohesion between them, and as a result, the reading experience is all over the map. Furthermore, outside of one or two exceptions, there’s little sense of Texas identity or history put forth in these stories. Since “Texas” shows up twice in the title, that seems like an oversight.

The collection starts off with a look at extreme pain management in David Bowles’ “Shrine,” which follows the latest efforts by Marisa, a woman who’s been plagued for decades by crippling headaches that make migraines look like paper cuts. After meeting an older woman, Sara, at a shrine, Marisa is convinced to take a trip into the mountains to a holy place for Sara’s ancestors to try and use a stronger magic to get rid of the pains that threaten to kill her. It will not come as a surprise to readers that Sara’s efforts will have a different outcome than Marisa expects, but Bowles toys with expectations a bit by making Sara and Marisa human, relatable characters, and if the journey is completely familiar, the ride is pleasant enough.

Next, it’s time to hit the road with the great Joe R. Lansdale, who’s featured here with his much-reprinted “Not from Detroit,” a sweetly amusing story about a man facing off with Death to keep his wife by his side. The story—which opens with a long-married husband and wife talking about their health before seguing into a passed-down yarn that proves to be foreshadowing—features the sharp dialogue and character work that Lansdale is rightly noted for, but in terms of tone and setting, could take place almost anywhere. This lack of specific identity is particularly unusual from Lansdale, as many of his best-known works are so redolent of East Texas (particularly the Hap and Leonard novels) that you can almost smell the heat and pine on the page.

From a dark night with Death, readers jump into the near future with “Ten Digit PIN” from Anna L. Davis, a tale of rogue robots and transhuman gadgetry under unblinking neon lights. Sawyer, a young man with an extensive tattoo collection, meets a biohack artist at his local shop one evening whose story of her latest client, a woman with a deep fetish, maybe even obsession, for body tech catches his interest. What starts as a friendly test session—and maybe a chance for some good times to come—turns violent all too quickly when the client’s new drones turn out to be far less interested in control than violence. Davis has a good eye for detail and a fine grasp of elliptical dialogue, but there isn’t enough substance to the story to be more than a violent encounter resolved far too quickly or neatly to be of interest.

The collection takes a turn for the creepier with “Sad Potatoes” by E. R. Bills, a simple tale about a simple man, Ben, whose patience, gardening skill, and gentle empathy for the pain of others lead him to an unfortunate place. Raised by his religious aunt, Ben believes deeply in the idea of a better place, and after attending several funerals and seeing the pain of grief on so many faces, an idea occurs to Ben on how he can help relieve so much suffering. No surprises here, but Bills’ leaves just enough hints as to Ben’s backstory to suggest that there’s a longer, stranger tale waiting to be excavated from this ground.

No matter how natty or suave one might be, sometimes you just can’t find anything to wear, as Stephen Patrick shows us with “The False Face of Donovan O’Grady.” Kihatomen, the Flayer of Souls, is out for a stroll upon the Earth, and he’d kind of like to blend in with the locals, but even demons have to follow rules. Any flesh he takes has to be freely given, or else it rots quickly, and Kihatomen isn’t used to asking. Still, when a passel of Texas Rangers comes his way, the Flayer sees an opportunity to get what he wants, and if it happens to help a disgraced younger lawman along the way, so be it. Patrick takes an unusual tone with this story, as it always seems to be just on the edge of parody, but never quite tips over. The story doesn’t quite work—readers might find themselves poised for laughter that never comes—but it fails in an interesting direction.

Some people are haunted by ghosts they can’t name, and one such soul is at the heart of “Daniel’s Dilemma,” an uneasy mix of potential and pathos from Carmen Gray. Daniel, a musician with chromesthesia, lives a ramshackle life in Austin, working a go-nowhere day job when a cat comes into his life. The cat, dubbed Sr. Rey, has quite an injury, and when Daniel calls the number of Sr. Rey’s tag, he ends up speaking with Maya, a little girl who is haunted by monstrosities that are far more real than any ghosts could be. More than Sr. Rey connects them, but it isn’t clear that whatever connects them can save Maya from a horrible, sadly common fate. The tonal mismatch between the two main characters is a jarring one, and Gray ends things in an abrupt fashion that leaves the supernatural potential ambiguous, but Gray’s skill in evoking a specific setting and character beats gives the story a lingering power.

In one of the few attempts to invoke a sense of Texas’ history, Bret McCormick takes an epistolary tack toward a bloody, racially charged past in “Crepuscular,” an ambitious but disjointed ghost story powered by a hatred that is unfortunately not dead. Constructed as a journal, the story follows Richard, a bookseller turned handyman who becomes the live-in caretaker for a couple of college friends. The town, a small East Texas burg that started as a freedmen community, has an occasionally ugly history, and Richard finds this out when a couple of ghosts move in on the property. The ghosts are the least of his worries, however; it’s whatever summoned the ghosts that Richard has to watch out for, along with the reminders that, to paraphrase Faulkner, the past is neither dead nor past. One of the strongest stories of the anthology, despite the disjointed nature of the story and the occasional diversion into metaphysical noodling.

With “Pretty Deaths,” Russell C. Connor takes the oft-visited trope of bored teens doing bad and transports it to one of the more unique settings of this collection: a body farm. Three teenage girls—Willa, Kit, and Mandy—break into a secured property run by the local university to see the body farm, an area where corpses are set up in a variety of environments and physical conditions to study insect action, decay, and other forensically useful aspects of the dead. Willa thinks this is all part of helping Kit get over the death of her father, and maybe a way to reignite their friendship. Willa is mistaken. Fortunately, Willa is also not the shrinking violet Kit and Mandy think she is. Connor writes with precision and efficiency, and the setting is uniquely morbid, but no surprises are offered along the way.

With “The Interrogation of Horace Chatham, Esq.,” Michael H. Price goes for a broad, parodic tone in his narrative of how Horace Chatham, a local meathead, ended up stealing a frozen corpse from his university employer and taking it home for purposes less than morally upright. Dipping in and out of dialect, Price’s story suffers from an excess of contempt toward the title character, with not much more respect being offered to the other characters, who come across as a fairly standard collection of law enforcement clichés.

Speaking of law enforcement, Tom Bont’s “Redstick” follows a no-nonsense FBI agent whose investigation of a child killer’s disappearance takes a hairy turn when she finds the town where he disappeared has a long history of disappearances and a short fuse for criminals. Refreshingly, the story’s protagonist, Agent Angela Hollingsworth, doesn’t waste time denying the evidence of her senses when confronted with the supernatural, nor does she try to convince others of what she’s seen and risk coming off like a loon. This practical stance, along with Bont’s patient world-building and controlled pacing, make the story flow assuredly, and like many other stories here, the ride is fine even if the destination is familiar.

Most of the attempts to go light in this anthology meet with limited success, but Ernie Lee manages it with his amusing “Minor Details,” which tells the story of Charley, a working man who starts off his day with a murder…or maybe not, and ends his day with his loving wife, who jokes about a murder of her own…or maybe not. Mixing the prosaic (hey, a bonus at work!) with the monstrous (hey, got to get rid of the corpse!), Lee shows us that even murderous lunatics need grocery lists and reminders to take out the trash. By not making a show of it, Lee manages to keep things zippy, all while maintaining the authorial equivalent of a straight face.

Ever taken a look at a possum? They’re kinda cute, but not really, and David Robledo takes that ambivalence to heart in “Taquache Nights,” a story about a community activist who finds a way to take more direct action for his home than going to meetings. Kiki, a long-time activist and public presence in San Benito, has been fighting City Hall to protect his beloved Conjunto Music Hall of Fame, but local business interests don’t see it that way, and one developer in particular takes great pleasure in outmaneuvering Kiki. However, one thing San Benito has plenty of us is possums, or taquaches, and simply through his usual practice of being kind and respectful to all things, and specifically helping taquaches when trapped in garbage cans, Kiki has made many friends. While the story seems to stop rather than organically end, Robledo’s narrative raises some intriguing questions, and the refusal to paint the taquaches as malevolent almost gives the story a documentary feel to interesting effect.

Of the stories in this collection, one of the few to actually approach disquieting is Alan Beauvais’ “Bamfires,” which reads as a hillbilly homage to Richard Matheson’s “Born of Man and Woman” in its telling of a vampire problem in the woods near a dysfunctional family’s home. Told from the perspective of a boy who is far more cunning and perceptive than his family credits him with, the story is simple yet unnerving in its illustration of how children see the world, and the kind of negotiations they might make if given the opportunity. Beauvais’ work is short, sweet, and effective.

Michael Baldwin plays a game of high-tech fakeout with “Winging It,” a story that starts off in one direction, pushes at the fourth wall, then spins around and goes for the jump scare. Jeremy Slater, a sky marshal with Homeland Security, is assigned to a flight aboard a brand new 797 jetliner, which suits him just fine. The flight seems pretty routine, but it’s not long before he looks out the window and sees something out on the wing. Of course, Jeremy has seen that Twilight Zone episode, so he’s not worried. He even has a high-tech explanation for it, which the flight crew confirms…until he reports something that shouldn’t have been possible. Not particularly scary, but as a knowing, light-hearted riff on a classic TV episode, Baldwin’s slight O. Henryesque tale works just fine.

In a complete change of tone, Glen Coburn paints a pastoral picture of friendship that draws a haunting from two deceased children in his edgily lyrical “The Burned Boys.” Kevin, the new kid in school, is befriended by Freddie, whose home out in the country seems like a paradise to a kid who’s just moved from Kansas City to the Texas hinterlands. Exploring the woods, the creek, and the fields that surround Freddie’s home fills their days away from school, and life is grand until a plane crash on Freddie’s property kills two young passengers. Worse, their shadowy presences seem to be hanging around, and whatever their purpose is, Kevin and Freddie don’t think it’s a friendly one. Like many stories, Coburn’s tale is about more than what it’s about, and though the hauntings get more and more severe, the friendship between the two boys never falls out of focus. If Terence Malick wanted to adapt a short story into a film, Coburn’s work here would make a fine candidate.

If H.P. Lovecraft had ever come to Texas—perhaps to visit Robert E. Howard—he might have come up with something like “Sky of Brass, Land of Iron” by Joe McKinney. The story of Robert Garza, a policeman whose research into an old church found on a friend’s land uncovers horrible secrets, certainly would fit into Lovecraft’s oeuvre. A twisted, incestuous family practicing dark secrets, mysterious texts referencing obscure practices and malevolent entities, even tentacles: frequent visitors to the Cthulhu Mythos should feel right at home. And yet, while it all hangs together, it doesn’t quite move. McKinney’s story hits all the right beats, and puts all the pieces in place with sharp prose, but it just never coheres into the otherworldly menace that Lovecraft is best known for.

Finally, Tom Alexander brings the collection to a close with “Substitute Player,” a cautionary tale about Billy Churl, a musician who went looking for a good time and subsequently wakes up in a basement with a massive headache and an inability to move. Searching his memories, Billy pieces together the events of the night before, which started well but went downhill in a hurry. It’s not until the last line, though, that he realizes just how downhill things have gone. In some aspects strongly reminiscent of Stephen King’s “The Breathing Method,” Alexander tells a down-and-dirty story with verve and speed, getting to his kicker efficiently.

Overall, this collection is a good example of the strong writing and varied styles available in Texas at this moment in time. Many are inventive in how they go about what they’re about, and a couple of them succeed in at least being eerie, if not frightening. If you’re looking for scares, this may not be your best pick, but as a collection of supernaturally themed stories (though some of the stories feature monsters that are wholly human), it works just fine.