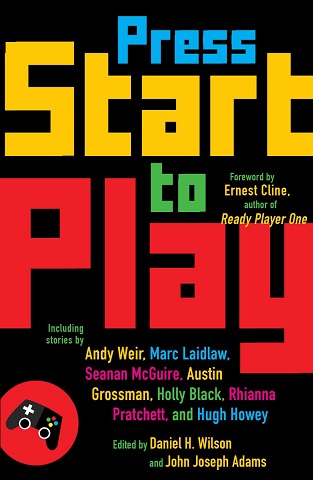

Press Start to Play: An Anthology

Press Start to Play: An Anthology

edited by John Joseph Adams & Daniel H. Wilson

(Vintage paperback, August 18, 2015)

Reviewed by Martha Burns

The stories in Press Start to Play offer up comedy, drama, and social commentary, all set in the world of video games and gamers. I’m only reviewing the original fiction and more than half of those aren’t merely good, they’re very good. The anthology will delight readers, gamers and non-gamers alike, and even the frustrating stories are worth it in that they’re frustrating in interesting ways. While understanding and enjoying the stories doesn’t absolutely require a knowledge of video games or of the contemporary state of gaming, some familiarity will make for easier reading. With that in mind, if you are not up on your kinds of video games or gaming news, this introduction is for you.

First, a brief primer on kinds of video games that show up in the anthology. Some of the games focus on exploring or having adventures in a fantasy world. Many, many of the stories in this anthology try to replicate the experience of text-based interactive games that guide the player through an adventure. These are some of the earliest games, the digital equivalents of the old “choose your own adventure stories” with blocks of text and one or two choices such as “open door” or “pick up item.” The iconic adventure game of this sort is Zork, where you play as “Nameless Adventurer.” A story that directly plays off of Zork shows up, so if you didn’t know, now you have a little insider knowledge. Some stories involve exploring a rich fantasy environment and solving puzzles along the way like, say, Myst, and games like that show up as well. There are real life simulations like The Sims where people build things, get food, shop, and do what they would do in the ordinary world if the colors were much brighter.

Other games that make an appearance are primarily about role playing. The role-playing video games most people are familiar with are those full of quests, killing monsters, and earning armor that upgrades as you play. Think World of Warcraft. Some role-playing games integrate the real world by asking players to go to real places and collect items for a treasure hunt or to meet other players. Others are training simulators, which might train you in firearm safety or how to operate equipment that you might want to practice operating before you go squash someone (the company John Deere, for example, has backhoe simulators). There is a story here about a simulator to teach recruits how to operate a frightening weapon before they blow civilization up but, alas, no backhoes. There are a fair number of stories that involve shooters like Halo, where the game play involves creating a fantasy character to shoot things.

In some games, the puzzles are front and center. Some focus on a player mapping out battle plans. One of my favorite sort of strategy games involves, not fighting, but manipulating economies, social organizations, and making ethical decisions for your own fantasy world. The term I occasionally see here is “decision-making game.” The best game out there like this is, in my opinion, the relatively recent Long Live The Queen, which I suspect one of the authors has played. The puzzles can even be real-world puzzles. Scientists sometimes post problems they could not solve online, format them as games, and ask people to solve them. It’s worked. The most famous example of that is the game Foldit where scientists asked people to help with a puzzle involving the elusive structure of an enzyme in an animal disease with some similarities to AIDs. Gamers solved it. Yes, there is even a game like that in this collection. There are also games that teach children about subjects they tend to find boring. The most famous of those is the history game Oregon Trail, the fun of which is, in part, all of the fabulous ways you can die in the days before antibiotics. Oregon Trail makes an appearance in this anthology.

There are other types of popular games that do not show up—sports games like Madden Football, music games like Guitar Hero, exercising games like the various Wii games for yoga and zumba, games that focus on raising virtual pets like Tamagotchi, puzzle games built on pen and paper puzzles like Sudoku, and puzzle games made specifically for digital formats like Angry Birds and Candy Crush.

One of the biggest pieces of news in gaming is their popularity and the seriousness with which they are now treated. Fifty-nine percent of us play video games. (My statistics come from various sources, but they are all collected in one handy place: http://www.bigfishgames.com/blog/stats/). Jane McGonigal’s Reality Is Broken is a New York Times bestseller that focuses on the positive aspects of gaming and in it she argues that we can use game mechanics and the way they reinforce positive behaviors to get people to do the praiseworthy things, a concept that’s called “gamification.” Gamification has become a buzzword in education, business, and science. I’ve mentioned science games with real-world applications above, but I should also include McGonigal’s game SuperBetter, which is a social game designed to treat depression. Impressive stuff.

Another big piece of news concerns the demographics of players and it explodes the stereotype of gamers as white, lonely, fat, potentially homicidal boys in their parents’ basements. Studies show parents play with their children and 56% think games have a positive effect on their kids. They also show that women and girls make up 48% of gamers in the U.S. (and 52% in the U.K.), and most players are over thirty. Indeed, only 29% of gamers are under 30. The statistic I love most is that there are more gamers over 50 than are under 18. I think that very few of the older players are in their parents’ basements. Many of the most popular games are, in fact, social games. As to race, only half of gamers are white.

The gamers in Press Start to Play reflect the actual demographics of gamers rather than the stereotype. Some of the characters in these stories play alone, some play with friends, some parents play with children, and not all of the characters are young, male, and white. Suffice it to say this anthology does not reinforce the stereotype that all gamers look alike.

A truly curious thing about the anthology is the old school stereotypes about gamers that it does reinforce. We have some fatness, some isolation, and some sternly worded screeds on the need to get some sun. I’ve long suspected that a principle of cliché conservation exists in literature, although usually I note it when a male author tries very hard to include a strong female character and then goes on to loving describe her breasts as she walks across the courtyard. (Yes, I am looking at you, George R.R. Martin!) It’s cheering (in a way) to note that the principle of cliché conservation applies in a situation where stories get it right that gamers can be of many ages, races, and sexes, but still lectures us on the dangers of getting fat or of preferring fantasy to the real world. It is, as always, disheartening when writers attempt to counter one set of clichés only to fall into others, but principle of cliché conservation might just be a natural law.

And then there is the biggest news in gaming, which involves that actions of a group that, like Voldemort, it is best not to name lest one call them forth from the Internet to spew their venom. Recently, some women in gaming have been the targets of horrific abuse. The women who have received the brunt of the abuse include the feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian (who has recently been included in TIME‘s 100 Most Influential People), the comic actress and writer Felicia Day, and the game developers Brianna Wu and Zoe Quinn. The vitriol involved death threats, rape threats, and a variety of odd conspiracy theories. There have, however, been significant positive shifts as a result of the media covering the story. People are now aware that nearly half to more than half of gamers are women. They also know that although the developers at big name companies are overwhelmingly male, there are a number of less well-funded and very good games women are making outside the mega-corporations. In addition, some big gaming companies have come down extremely hard on misogynists, much harder than they needed to if they were only worried about their image. Blizzard, the makers of World of Warcraft, used part of the opening speech at their 2014 Blizzcon to call out the group responsible for the abuse and to say misogynists aren’t welcome to play in Blizzard’s virtual toy box. That made it very clear that this is not a fringe concern in the gaming community, but something we all care about. As a result, we are hearing less from the group behind the attacks on Sarkeesian, Day, Wu, and Quinn since Colbert made fun of them. Gamers, as it turns out, do not want to be associated with any group Colbert mocks. But that does not mean attention to the issue of Internet abuse, in particular that directed towards women, has waned. Due to the coverage, Reddit, Twitter, and Facebook have begun, at long last, to create rules about abusive speech and intimate images used for revenge. The bad effect of the coverage is that in the popular consciousness, gaming has gone from being the thing that makes you fat, homicidal, and antisocial to the thing that makes you a tinfoil-hat-wearing misogynist.

There are stories in the anthology that directly address what it is like to play specifically as a woman but, sadly, all of them are downers and/or preachy. It’s true that the stories in the anthology have a number of female gamers represented and some female developers, and that’s commendable, but we do not have what the media has so beautifully obscured. The media highlights the misogyny directed towards female gamers in part because if it bleeds it leads and because we were unaware. That’s what makes it news. We’re missing a focus on our female-centered fun in the news and I would hope that the anthology would give us that. It would be easy to do. Anita Sarkeesian’s video game critiques are smart and snarky and they come from a feminist gamer. Where is our smart, feminist snark? Felicia Day’s now-completed web series about a World of Warcraft guild is The Guild. Half of the members are female, including an unemployed violinist, a stay-at-home mom, and a cruel and heartless player. It is hilarious, lighthearted, and highlights some ways in which women not only have different lives from men, but the ways in which that translates into their positive experiences as players. We get a story that’s supposed to be about the joy of playing as a women, but it appears you cannot make that point without showing how narrow-minded men are and, no, this isn’t a story written by a woman. Where is our cute, female-centered silliness in this anthology? Where are our friendships with other women with whom we play? There is a bit of this in Cory Doctorow’s story “Anda’s Game,” which I haven’t reviewed since it is a reprint, but it isn’t so much about female-centered gamer fun as it is a lecture about third world economic oppression delivered, amusingly enough, by a man to a bunch of teenaged girls. There is male-centered fun here where women do not show up and that is not a bad thing in the least. Doing your own thing does not mean you deny others the opportunity to do theirs. Many of the stories show male and female gamers playing together and being supportive of one another and that’s wonderful, but where, specifically, is the fun female gamers have when no one else is looking? It is different and merely looking at the prominent female voices in gaming shows as much. I guess I’ll have to wait for there to be a Kickstarter, Women Destroy Gaming! I wish I didn’t have to, but I am very pleased that so many of the stories in the anthology do reflect the pure joy of gaming either alone or with others, and I am pleased that the stories showcase the variety of races, sexualities, and ages of gamers. I also enjoy the way that in these stories, games so often intersect with and offer commentary on the real world—you know, that thing we occasionally see from our basement windows.

In “God Mode” by Daniel H. Wilson, a man designs a video game and, as he does, the real world begins to disappear. As he tries to hold onto reality—especially the existence of his girlfriend, Sarah—he struggles to understand what’s happening. He asks himself whether his video game is replacing the real world, whether it is all a dream, and whether or not aliens are behind it all. What is interesting about this story is that the answer to his questions, when it comes, is not the point of the story. This is impressive since your average reader of science fiction is quite used to those choices, which verge on cliche. There is no twist, no new explanation for the real world disappearing, and although the usual questions have propelled the plot, the focus of the story centers on the importance of human connection. That, too, could be cloying or cliché. Instead, we empathize with the protagonist as the world slips away. That experience isn’t restricted to science fiction, but is, rather, a component of the human condition. We love, we’d give the world for that love, and yet even the most intimate relationships involve distance and the desperation that results when we realize we cannot bridge it. Recommended.

This next story focuses on the non-player characters in video games. These are the characters with a static role and pre-programmed dialogue. Every gamer has had a moment where you wonder just what they’re thinking and whether their existence is tragic or fulfilling. Bits of dialogue can seem ironic or funny. The flight masters in World of Warcraft say “Keep your feet on the ground” before they give you a ride on an eagle. What’s up with that? The premise of “NPC” by Charles Yu is that these characters have minds of their own. Here, a male NPC who works as a miner on a moon base demonstrates a bit of independent thinking and the powers that be promote him to an in-game, interactive character, controlled by a player. The problem with this is that now his body is controlled by outside forces in every tiny respect, whereas previously his devious little mind could do whatever it wanted as he repeated his pre-set motions. In real life, this would be the story of a slacker who can either be a corporate drone or someone whose less demanding job allows them quality time with friends and the opportunity to develop outside interests. Setting that choice in the world of video games is clever and results in a fun story that gives great insight into the mindset of gamers, who are often far more interesting (in my humble opinion) than people who fit society’s expectations of success. Recommended.

A Japanese worker in a beef bowl restaurant discovers his soul is immortal. You’d think this would be great news, but this causes him some distress because his immortality amounts to inhabiting body after body. He wonders whether he has any true self at all. The average reader would tell him, “Your self is your soul. Duh. Relax.” The strength of “Respawn” by Hiroshi Sakurazaka (translated by Nathan Collins) is that it leads us to question the assumption that the soul is our consciousness. That’s intriguing, but the story is only given a tenuous connection to gaming. This is more of a standard-issue science fiction story with a mere gesture towards gaming. Recommended for the story’s theme and character development, but this story feels out of place in this particular anthology.

Video game worlds can be creepy in the extreme. So it is in “Desert Walk” by S. R. Mastrantone in which a games blogger gets the career-making opportunity to play an elusive video game and interview the even more elusive developer. On the surface, the game seems simple enough and more like Myst than Silent Hill (an iconic creepy game). The tension and weirdness build nicely as we go from walking through a fantasy world and trying to find hidden clues, to finding things that make us uncomfortable, even question our sanity. Although the reveal isn’t much of a reveal, it generally isn’t in horror adventure games. It doesn’t matter in those games because the focus is always on the unsettling adventure. The story captures that experience beautifully and uses an electric kettle to good effect. Recommended.

One of the most inventive stories of the anthology is “Rat Catcher’s Yellows” by Charlie Jane Anders. Grace watches as her wife, a former Ph.D. student, slowly slips away from an illness that results in a blend of autism and Alzheimer’s. As a way to give Shary a connection to something, Grace buys the fictional game Divine Right of Cats and Shary not only connects with the game, she quickly becomes a master, as do many others with the same affliction. This is a new take on video game absorption in which what seems to be a disconnect from reality yields connection in large part because of the connectedness amongst both players and the families of players. Make no mistake—Shary is not cured by the game, nor does Grace’s life become perfect. This story contains not a single cheap move and not an ounce of treacle despite a set-up that could easily be soaked in both. Highly recommended.

In “1Up” by Holly Black, a young woman travels with two people she met online to attend the funeral of a fellow gamer. Once in Florida, Cat and her friends discover that Soren (who goes by the screen name Sorry), made them one of those old-school text-based adventure games. The game is filled with hints that Sorry didn’t die from natural causes and the murderer is still out there. The story is deftly plotted with amusing dialogue. It’s a positive take on gaming friendships and a welcome, upbeat use of teen characters. Highly recommended.

Artie and Ani are cousins with magical abilities. To avoid getting sucked into an alternate dimension, they try and solve a number of puzzles in yet another text-based game in “Survival Horror” by Seanan McGuire. The story, which is fun as it’s being told, ends without complete closure, which either signals the beginning of a series or a story in which the author does not nail the ending. There is witty dialogue, a gentle bond between the cousins, and a truly excellent joke about Windows 7. Let’s hope this begins a series because we need more adventures from these cousins. Recommended.

“REAL” by Django Wexler is the second story in which someone tracks down a developer of a potentially nefarious game. This game, REAL, is an alternate reality game with a real-world component, something like a video game story that requires a treasure hunt in real life. The players in REAL begin disappearing. The developer, Aka, knows what’s happening, but he’s none to eager to tell. His story is so fantastical he’s convinced no one will believe him and he’s left the project because he cannot get the financier to stop the game. What exactly is going on feels extremely over the top, even for a video game, and clashes too much with the initial tone of the story, but there is a nice reveal regarding the identity of the journalist.

Esme is a disappointment to her father in “Outliers” by Nicole Feldringer. The old man had wanted Esme to take over his business empire, but all she does is play her blasted games. Esme is an engaging and fun character and when Esme begins playing a game to help scientists study data on climate change, her family’s business and her gaming life come together. While the resolution is satisfying, the story suffers from needing to be longer, almost as if Feldringer rushes through the science out of fear of boring readers. Science fiction readers like the science though and by skimping on the science, which is the focus of the game, we’re also rushed through the particulars of the game play. Without those elements, we have little feel for the immersive quality that draws Esme in, which is a shame because the game, in outline, sounds as if it could be great fun.

“<end game>” by Chris Avellone uses yet another text-based adventure game. If Warren makes the right moves as he makes his way through the world, that is, if he turns on the right light or chooses the right door, he wins. What is so often satisfying about these games is that when you do make the right choice, options that weren’t available before open up. Hence the game gives you an opportunity you never get in life to explore even the simplest decisions you make and learn about their consequences. The payoff is none too exciting in this story, but that doesn’t seem to be the point. Again, that tends to be how these types of video games work, but it is a big risk to do that with multiple stories in one anthology. Yet Avellone builds tension well as Warren replays, changing tiny things. The danger is that seeing this in a story where big chunks of the same text show up over and over again with only mild changes can be tiring. Amazingly enough, Avellone pulls it off, though at this point in the anthology, one might be a tad tired of the walls of text that define these types of games. Text-based interactive video games lend themselves to representation because of those walls of text, but there is also a good reason these games have waned in popularity. Recommended for the tension.

“Roguelike” by Marc Laidlaw uses another text-based adventure game to good effect. You, a nameless agent, must kill an evil emperor. If you fail, you die, and this game is generous enough to make the deaths silly, which is good because you die often. On screen, you suddenly see a tombstone and including the graphics in the story increases the enjoyment. It is a humorous, quick read that captures the revenge one wants, sometimes desperately, to enact on the game. Recommended.

One of the most popular games in the nineties was Oregon Trail. In that game, you gather supplies for your group and, well, lead them across the Oregon Trail. Kids can learn about decision making and learn some history to boot. Bad, bad things happen as you make your way out west without antibiotics. The tragic end most of the original players associate with Oregon Trail is dysentery, though there are also snake bites, frostbite, and starvation. What was not so satisfying about Oregon Trail is that these elements can appear randomly and are not always the result of the player’s choice. Most recent books on game design suggest not doing this to players. A little random tragedy goes a long way. In this eerie version of Oregon Trail, the player is rewarded for killing his or her group in as grisly a manner as possible, even when that has real world consequences. Lizzie, the protagonist of “All of the People in Your Party Have Died” by Robin Wasserman, is just the sort of self-absorbed person who would sacrifice anyone to win. Lizzie doesn’t think she’s that sort of person, of course, and I suspect that the point of the story is to show Lizzie her true self. The story falters by overplaying its hand and making Lizzie obnoxious to a degree that one begins to suspect the character only exists so that the author can loathe her.

Jimmy wants a job at a gaming company, so he’s asked his buddy who works at a gaming company to help him out. The buddy, Ross, gives Jimmy the keys to his office so that Jimmy can see the newest first person shooter before its official release. It’s always best to tailor yourself to the employers’ needs, after all. As Jimmy plays, elements of the game bleed through until it begins to look like this isn’t a virtual shooter at all, but a real world battle against bad guys. “RECOIL!” by Micky Neilson is best when it’s offering gentle wink, wink, nudge, nudge moments regarding some of the sillier tropes in shooters. These include the tropes that the black guy dies first, the perfect weapon suddenly appears right when you need it most, and the girlfriend shows up late so that the reluctant hero has a reason to fight. The story falters when we have too much about the shooter gameplay. Hearing someone strategize the way they do in a game—running through the fifteen possibilities, reminding yourself of your last moves, gauging distances—is not so exciting unless you are specifically tuning into Twitch to watch someone play. Here, we’re tuning in for a story and don’t get enough of it.

There is meme going around the Internet that draws a comparison between, on the one hand, race and gender and, on the other hand, player stats. Stats primarily refers to the quality and attributes of armor. The better your armor’s stats, the easier it is to defeat monsters or other players. I see plenty of players with great armor who play well, but their success, at a certain level, is not so impressive, particularly when you factor in the game’s desire to reward good armor without it being tied to skill. Sometimes armor is a random drop and sometimes it’s a reward for your team killing a big bad monster even if you were a greater liability as a teammate than an asset. Sometimes, though, you see a phenomenal player in crappy armor just blow you away with their skill. It’s a challenge some great players set themselves when they have no more big bad monsters to down. I’ve only seen someone kill something hard to kill with truly awful armor once and it was a thing of beauty. So imagine life was a game, the stats of your armor were random, and you don’t ever get to re-roll or upgrade. It’s like that. You get the analogy. “Stats” by Marguerite K. Bennett takes this meme and runs with it. A game developer has found a way to manipulate the attributes of human beings and she tries it out on her entitled boyfriend. His changing stats don’t have to do with his armor though. He gets to live life as a ninety pound weakling, as a short man, as a black man, or, in the story’s best and most harrowing scene, as a fat woman. The funniest bit is the boyfriend getting the stats of an orc. Largely, this works because Joey is entitled and whiny, but not mean, and he is both indignant at his changing circumstances and genuinely hurt and confused by the results. He’s a git and yet you feel so bad for him. That said, the success of the fat woman scene, which is realistic without being too on the nose, makes me wish Bennett had done more with the other variable stats, particularly the ones that play with our notion of masculinity. Recommended.

“Please Continue” by Chris Kluwe is told from the perspective of a character in an action-adventure role playing game where the focus is on player to player combat rather than questing and fighting monsters. Toward the end, the story devolves into a vitriolic screed against gaming. The main character realizes “that a game is just that, and life is more than a game.” Insider reference to Zoe Quinn’s ordeal make an appearance, but these aren’t explained and, again, the focus is on misogyny rather than what women contribute. The implication here is that misogyny results from playing the game and not getting into the real world. There are so many critiques that can be made of gaming, but this shallow critique offers nothing new.

“Creation Screen” by Rhianna Pratchett is, in its message, nearly identical to Kluwe’s story. It starts as the story of a sentient avatar who becomes aware of her male player’s callousness and preference for an environment he can control rather than the real world. The avatar says, “I fear you are in this world more than I am.” In other words, the player needs some fresh air.

A boy struggles with his parents’ divorce while also negotiating the alternate reality of (yet another) text-based video game in “The Fresh Prince of Gamma World” by Austin Grossman. Kudos to the author for representing a fictional world as having a positive impact on a player, which is part of a fine tradition in science fiction and fantasy in which literature can give one solace and hope. When a writer uses that technique, the analogy between the reader’s life and the story is generally clear. Here, the comparison between the boy’s life and the game is not obvious, which might have been a plus, but the similarity seems a far stretch and Grossman’s attempts to make the comparison clear in phrases like “you think your father might have split the world just as a way of winning a divorce settlement” are heavy handed.

A new graduate from the Shuos academy meets a military legend who introduces him to a battle simulator. It’s a training tool that the Kel, who are sometimes Shuos allies and sometimes the thorn in their sides, made to train soldiers to be prepared to make some hard choices in their battle against the Taurags. Only a simulator will do because a new weapon is so lethal that it’s impossible for soldiers to experiment with it in the field. “Gamer’s End” by Yoon Ha Lee has interesting things to say about what sort of soldier would ultimately make the best soldier in this situation and it has, in addition, interesting things to say about learning from the enemy. This is all done in the context of a traditional shooter. It feels like a shooter, behaves like a shooter, and when the player does what players tend to do in these stories and begin to question whether this is a shooter, the move is made smoothly. Recommended.

“Twarrior” by Andy Weir is a hilarious send up of one of the most grating, tired tropes in science fiction—the horrors of a sentient AI. What if a game developer did accidentally create a sentient AI? How would it speak? How would it reason? What would it truly think of its creator? The story suggests that if a sentient being learned language and morality from social gaming, you wouldn’t get Sky Net, you’d get a potty-mouthed sweetheart. Highly recommended.

“Select Character” by Hugh Howey is meant sincerely, but is condescending and, in its attempt to show the difference between male and female gamers, gets the economics of role-playing action-adventure games wrong. The story revolves around a husband being shocked, shocked I say, that his stay-at-home wife plays his game. She also plays it “like a woman,” which is to say she is interested in the game’s garden a bit more than in fighting. She becomes a true hero when she cleans a wall. That isn’t the problem I have with the story. The problem I have is that the stereotypical female activities are hidden in the game and don’t help the game’s warriors. This makes “playing like a girl” something different that games do not encourage. It’s at this point that Howey gets it dead wrong. A way that games keep players hooked is by layering different types of gameplay. This plays against gender stereotypes in some instances because games integrate traditionally feminine “helper” activities and give them an important role in the game. There are games with both gardens and fighting and in those games, warriors respect the gardens because the best food gives the best stats. The result is that what you do in your garden not only helps fighting, but if you make the best food, you can sell it at the auction house for high prices to players who only like fighting, not gardening. Those who craft armor also make a killing at the auction house. Sometimes that’s because the crafted armor is better than anything you can get in a fight and sometimes it’s because the armor is pretty. Players can buy the pretty armor and then use a special mechanic in the game to make their high quality armor look like the pretty armor. It’s called transmogging. Men love transmogging their armor, which is to say, they sure do like dressing up in game. Hence a virtual environment is a place where gender roles can become fluid. These aspects of game play could give Howey the point I suspect he wants to make, which is that traditional women stuff is valuable in games. Eventually, the wife is rewarded for her feminine gameplay, but it’s unclear whether she wants the reward. If only he’d used the games properly. Disappointing both for the story we get and for the story that so easily could have been.

Press Start to Play reflects the varied kinds of video games out there, the varied player base, and how games intersect with and comment on the real world. Some of these stories give a good scare, some provide grown up drama, some show gameplay fun either alone or with friends, and some are laugh-out-loud funny. Some of the wittiest moments function as easter eggs, those little prizes developers hide in games to reward devoted players. A few of the stories ask the philosophical questions that have defined science fiction. What is it to be human? What defines reality? Is it better to be a corporate drone or a slacker? The anthology is weakest where it tries to be bravest and that is where it offers up commentary on misogyny in gaming. A good, solid essay on gender and gaming would have helped and left space for writers to explore the ways in which games question gender norms. With one exception, the stories that focus on misogyny feel heavy-handed and overly simplistic. None of the stories here are willing to take on the best moment of every female gamer’s life—that moment of freedom where you don’t have to worry about haters, when you know this world is made for you. Sure, it’s a fantasy, but this could be a fantasy that provides a road map to a better world.