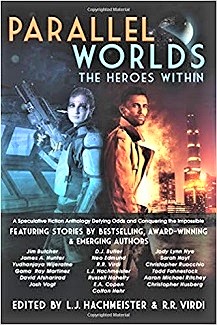

Parallel Worlds: The Heroes Within

Parallel Worlds: The Heroes Within

Edited

by

L. J. Hachmeister & R. R. Virdi

(Source 7 Productions, October 2019, pb, 408 pp.)

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

Parallel Worlds offers nineteen authors’ short stories intended to shed light on the sometimes-blurry line between a story hero and a well-crafted villain. The works range from high fantasy through urban fantasy to science fiction, and their tone ranges from somber to comic. Several are set in existing fictional universes readers may already know, and others stand alone. Whether or not the anthology teaches you anything about villainy, there’s quite a variety within its covers and good odds there’s a story you’ll want to read in Parallel Worlds.

Sarah A. Hoyt’s “Dead End Rhodes” is SF set on a starship that serves as a traveling office for a detective cyborg who believes he’s a Great War veteran in New York in the ‘30s. In the tradition of a Sherlock Holmes story, the narrator is an assistant to the detective wonder, whose mental processes remain opaque and distant. It’s a dark world, and the wealthy client’s assignment reveals that the client’s problem is a lot bigger than he thought. The detective and his assistant earn their paycheck, but nobody wins. It’s satisfying to finally understand why the narrator is working with the detective: her background and motives not only reveal her humanity but, when combined with a kind of buried-alive horror story, reflect and amplify the winning-but-losing tragedy in the solved case.

Christopher Husberg’s “Look Me in the Stars” opens on a lonely and broken young woman giving up her blog (and hope), then due to the magic of reverse-chronological blog presentation she slowly rewinds into an optimistic zombie-apocalypse survivor keen to connect with the rest of humanity. Or perhaps you give up on the presented order and read them chronologically, from last back to first, paging back after every entry looking for the top of the “next” entry. There’s people who like digesting blogs like that, but it’s work: unless you’re watching Christopher Nolan’s Memento, the reverse-chronological format works against story. The upside of this presentation is the ability to surprise the reader with facts that would have been obvious if presented chronologically, and to present as bittersweet the opening-scene optimism we know will leave her too exhausted to bother connecting.

D.J. Butler opens “The Dead Who Care” on the protagonist spotting another traveler on a post-apocalyptic Utah freeway and slowing his Model T for a greeting. Butler’s alternate world combines fantasy elements (wolfmen, ghosts) with gritty real-world-feeling maybe-’20s elements like a recent Great War and dangers posed by strangers on an isolated stretch of highway in an era bereft of cellphones. When the protagonist meets a stranger’s ghost on the way home from failing to keep a promise to a battlefield buddy, he has no idea what kind of mess has entangled him and it’s fun to see him try to think his way free. The personal-scale stakes feel intimate and immediate, and the discovery what kind of problem confronts him has the delightful effect of inspiring him to go keep his promise. Nice tension, and an upbeat conclusion.

Set in the pun-filled world of the long-running Myth Adventures series, “Myth Deeds” by Jody Lynn Nye is the first person account of a M.Y.T.H. Inc. wizard hired to escort a titan into an alien dimension to win acclaim as a great hero. What could possibly go wrong? Lighthearted and humorous like the rest of the series, Nye’s piece is a fun fantasy romp that pokes fun at organizations you know. A good laugh. Okay—several good laughs.

“The Shadow of Markham” by R.R. Virdi is a fantasy set in a city that might be a dangerous place but, based on the opening lines, might as easily be sentient and hungry. Like some descriptions of Gotham in Batman, it turns out to be an anthropomorphic description of a city being itself. Despite the first-person narration the language has a high-fantasy feel: detailed descriptions, comparisons, frequent adjectives and adverbs. The piece does not disclose anything about the protagonist’s background beyond his membership in an oppressed nonhuman racial minority, but he comes off like a fantasy Batman: his belt pouches produce exactly what he needs several times during his evening outing, he accepts delay to do good for people who won’t possibly ever repay the favor, and he refuses to kill the awful villains he overcomes even when this places his city and its inhabitants in further danger. As in Batman, this works primarily because the protagonist outclasses in combat everyone who confronts him. Unlike Batman, we don’t know what’s motivating him, how he came to have enough free time to solve all these problems he’s tackling, or why it should make any sense the protagonist claims to be prepared to thwart the evildoers when they strike next—how does he expect to be able to work out where that will happen? It would be easier to accept the protagonist’s convictions with some insight into their origin, and more fun than trying to divine it without the author’s assistance.

Narrated by a schoolboy enamored with all things Davy Crockett, David Afsharirad’s “Davy Crockett vs. The Saucer Men” is SF adventure about the day aliens landed at the bend in the nearby creek. Chock full of totally-credible interaction between rival playmates, the piece has as much strength in its characters as in its humor. Leveraging the narrator’s fandom of Davy Crockett (who would never back down from stopping the alien invasion), the boy’s companions put him in a position to show true heroism. In the tall-tale vein of such stories as Crockett grinning the bark off a tree, we get to enjoy how the town was saved by a boy too in love with his idol to fail. Fun.

Aaron Michael Ritchey’s dark near-future SF heist “Dead Run” opens in a converted-to-multifamily house at the bed of a boy’s dying sister. His plan to fund her medical care pits him against his drunk father, a local gang led by his prostitute brother, and the security systems of offworld smugglers. For such a short work it’s rich in the awful details of a dark world full of terrible choices. If you love dismal near-future SF, it’s got the worldbuilding, characters, problem, and resolution to scratch your itch. Recommended.

Gama Ray Martinez’ “Unnamed” is a lighthearted sword-and-sorcery-and-cellphone adventure. The protagonist’s co-workers in his office job haven’t any clue about his secret duties protecting the world from supernatural threats—and they don’t accommodate that work while continuously scheduling meetings he must attend. This short story resolves one episode in what feels a Buffy-style monster-of-the-week universe. Most of the climax’ force comes from a character revealed as a legendary celebrity; it’s fun, but since the protagonist is never put in a position to make a hard choice we never learn what he’s really made of.

L. J. Hachmeister’s SF quest “Prisoner” presents like The Bourne Identity inverted: instead of a secret agent on the loose discovering himself while fleeing killers after accidental trauma caused retrograde amnesia, Prisoner 141 has been intentionally mind-wiped and sentenced to labor on an interstellar prison ship whose warden lines his pockets contracting for inmates to perform other hazardous duty (e.g., ordnance disposal). As in Bourne, tidbits of memory tantalize Hachmeister’s readers with the question who Prisoner 141 was, what she’s done, and whether she can win free—or will ever care to. Hachmeister builds a sympathetic character we care to know more about, and presents a mystery that’s hard to resist. Well done. Recommended.

James A. Hunter opens the Urban Fantasy “Valentine Blues” on a noir-vibe narrator driving into a “Podunk shit-speck” town with something “wrong” in it. The rough-around-the-edges narrator slowly reveals outrageous arcane power before riding into the sunset in his beloved El Camino. The surprises seem to exist largely to expose what a badass the protagonist represents: it’s urban-fantasy competence porn. If you like watching a protagonist slowly revealed to be an unstoppable whopping badass and crushing enemies like grounded gnats, this is for you.

Yudhanjaya Wijeratne opens “The Tragedy of John Metcalf” on an economy-class seat in a crowded passenger aircraft headed for the Ottoman Empire. It’s not clear the protagonist is a hero or even strictly a villain, but imagine a named-level character adventuring through a James Bond film set in a world of magic. The tale combines alternative medicine from India, ghost aircraft, parallel universes, paramilitary Church exorcism units, humanity and murder and the horror of loss and glorious redemption and victory—a damn good time.

Colton Hehr’s “Effigies in Bronze” opens on a military commander narrating a Bronze Age military fantasy to those who stand in judgment of him. The slow, deliberate pace may not be to every reader’s taste but it suits the plain-spoken narrator’s slowly-building climax. Like many short stories, it builds not to an answer but a question. This one builds to a question that turns on values: can you sacrifice yours, claiming perhaps that it’s the path of expedience or efficiency, and still claim victory? To pit morality against obedience or even results is common enough in stories about war not to draw comment, but it’s satisfying to see it done well.

E. A. Copen’s “Daily Bread” is an urban fantasy whose power as a story is built so heavily on reveals—who the narrator is, what his relationship is to the other characters, how he bridged from the homeless panhandler in the first flashback to the international traveler we see at the open—that it’s challenging to describe it for fear of spoiling even, for example, the plot structure. It’s gritty and dark and drenched in regret and fury and still manages an upbeat ending. The dark awful middle leaves one wondering how thoroughly the narrator has sold his soul and how dark a fate awaits those he greets as friends at the open, and the answer is convincing. Recommended.

Christopher Ruocchio’s “The Demons of Arae” is an interstellar military SF. As in Herbert’s Dune, technology has pushed war back into the age of sword, with powered shields and strange materials giving soldiers protection against high-tech ranged weapons so warriors come within hand-to-hand range for attack. Full of callbacks to battles from a prior age and myth, “The Demons of Arae” depicts ground forces described as hoplites, infantry performing shield wall formations, a labyrinth, even a wall-breaching colossus called Horse. The ancient/technological mashup is fun, and the body-altering enemy whose members can escape their bodies to return riding some new technologically-enhanced horror is a great adversary. The protagonist’s personal motives feel unclear, leaving one wondering what beyond the physical conflict is at stake.

Neo Edmund’s “A Tale of Red Riding: Seduction of The Werepire” follows a pair of mutually-infatuated werewolf teens on their hunt for a supernatural were-vampire, with whom Red is promptly incapacitated with infatuation. No explanation is offered why they’re hunting the werepire (he was supposed to be hot?) so it’s unclear this development represents a contradiction. The choices seem to be to interpret the story as a monster-of-the-week (no explanation is needed why we’re hunting X, it’s a new episode and they always hunt something because reasons) or to interpret the story as an attempt at erotica, in which no ‘why’ is required if the scenery and character action leads to a successful sexual encounter—which this does not. Readers of Edmund’s Rise of the Alpha Huntress and its sequels may have better grounding in the world’s magic system and the meaning of the story’s capitalized terms, but those expecting an urban fantasy may puzzle that Alpha werewolf powers include summoning sorcerous flame, wonder why werewolves would be connected to or depend on a crafted artifact like a magic sword, and struggle to imagine the appearance of “an amulet … illuminated with lunar energy.” Since the story hasn’t got an erotica resolution, and is challenging to accept as straight-up urban fantasy, it’s hard to characterize unless as a send-up of paranormal romance.

In “Threshold,” Todd Fahnestock delivers a fantasy coming of age. The close-third perspective follows a young nonhuman whose people live by a law requiring concealment from humans, with whom they’ve had disastrous experience. The youth knows he’s on the threshold of his becoming-an-adult decision—a life-changing rite of passage among his people—and wonders what it is until it becomes obvious. It’s a classic tough choice, perfect for a climactic decision. There’s beauty in watching a hopeful young person decide to save the world at any cost, and in watching people think for themselves instead of conforming safely to dogma; Fahnestock’s bittersweet climax delivers both.

Russell Nohelty’s “The Last Death of Oscar Hernandez” is a reincarnation fantasy set in the dismal future. Like Groundhog Day without the laughs, its protagonist is condemned to return over and over—though not on the same day—until he gets it right. In a kind of “back in my day” lecture the narrator decries the devolution of society and its people in a dismal spiral of dwindling resources and collapsing values. Naturally this leaves the protagonist as the most virtuous man in a world that has destroyed all the beauty it can and forgotten its humanity. Yay?

Josh Vogt’s One Last Job short heist fantasy “The Magpie and the Mosquito” surprises by providing in 5700 words all the elements readers expect in a properly-executed specimen of a heist and a one-last-job. A heist this short is a feat, as a heist requires gathering a team, preparation, execution, some unexpected development, the double-cross, the escape—yet it’s all there. Also, Vogt’s old-salt character pulling this One Last Job offers a delightful combination of outward presentation and contrasting inner life. Delightfully executed climax. Well crafted.

Set in the Chicago of Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files, “Monsters”—like other non-Dresden-POV short stories—offers fans a glimpse into that world from a perspective the novels can’t provide. Goodman Grey, the inhuman shape-shifter mercenary introduced in Skin Game, narrates a job for which he was hired by the crime boss Marcone, who wants a problem with a criminal associate resolved so it won’t trace back to Marcone. Entertainingly, the nigh-unkillable combat machine that is Grey can be found in an office with an assistant and conducting business through a formal legal entity (“Monsters LLC” sounds like a shout out to a very different business in Monsters Inc., and stands in a kind of smirking opposition to Monster Hunters International Inc., which in Larry Correia’s series is in the business of exterminating monsters rather than offering Monsters as a service). While there’s always some fun seeing wrongdoers get a good smackdown, there’s a certain Darkly Dreaming Dexter energy to “Monsters”—Grey, after all, is pretty bad himself. However, “Monsters” depicts a job undertaken for real merit: not because killing is fun, but—as we eventually learn—because there’s an offense to correct. And therein lies the question it raises: what makes a real monster?

Butcher’s fans always want to know what light a Dresdenverse short sheds on the Dresdenverse or its players. Given Grey’s inscrutibility in Skin Game, and his unexplained motivation to pay capital-R Rent (whatever that means), a Grey-POV story seems guaranteed to draw interest. Psych! Grey is no more transparent narrating “Monsters” than being talked about in Skin Game. What is interesting is that Grey’s assistant Vita knows him well enough to call him on his BS when he claims to take the job to pay ‘Rent’ (not explained so far), when it turns out he’s actually working to improve the world. Or perhaps to rehabilitate his dysfunctional assistant into a happier, more laid-back killer. Whatever it is, Viti is closer to understanding Grey’s mission than we—and, given the loner vibe Grey has been giving off so far, that’s kind of interesting by itself. Something matters to Grey, something beyond the Rent.

Back to the monster thing. Marcone is a human, but his criminal enterprise and that of his associates are the reason the story’s victims are in jeopardy in the first place. Marcone’s depraved (human) underlings are willing to commit offenses equal to those of Marcone’s loathsome targets. Grey’s dark assistant (Viti, a name that means “light”) sees betrayal and risk everywhere, to the extent of needing to be told children should be transported in the back seat rather than the trunk, and also not to kill them. Amidst this sea of darkness and inhumanity, Grey by contrast seems to be operating a charity, righting wrongs at one dollar apiece (think Encyclopedia Brown, solving mysteries for a quarter apiece, but bloodier). Who’s the monster, indeed?

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.