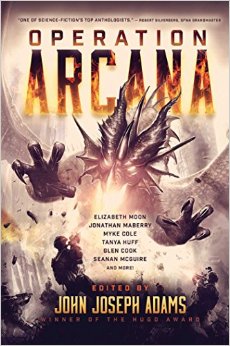

edited by John Joseph Adams

(Baen Books, tpb, March 2015, $15.00)

“Rules of Enchantment” by David Klecha and Tobias Buckell

Reviewed by Douglas W. Texter

Operation Arcana, introduced and edited by John Joseph Adams, presents sixteen military fantasy stories. A few of these tales haunted me. Many of them entertained me. And all of them presented solid work. Not everybody will enjoy every tale, but most readers will like several of these stories. One of the best features here is the range of political outlooks on war. Another laudable thing is the inclusion of a couple of stories either told from the non-American side of a particular conflict or overtly critical of the United States. Such inclusion is an act of literary and political bravery. A third strength is the range of sub-genres: from steampunk to an homage to Tolkien to an updating of Peter Pan to golem stories. This is a very worthwhile anthology, with something for every fan of military and fantasy stories.

“Rules of Enchantment” by David Klecha and Tobias Buckell serves up a fantastic what-if of mammoth proportions. The world of J.R.R. Tolkien smashes its way into our earth. First, it was just a few appearances in alleyways. Then, though, a full-scale invasion took place. Orcs and giant trolls invaded the earth. The story opens with a marine platoon pushing back in what appears to be Middle Earth. This story reads like Battle Los Angeles meets Tolkien. Warthogs and missiles strike out against giant trolls. I almost expected Aaron Eckhardt to arrive on the scene. The story is told from the perspective of a Marine staff sergeant. The Earthers are also in this tale making alliances with beings from the land of Tolkien, The tale contains a subtext about people who grew up thinking that Tolkien was fantasy. When the invasion happened, lots of people wanted to play Aragorn and received a rather nasty surprise. The characterization here is rather light, but the military terminology hits the mark, and it’s an entertaining piece of fiction.

In “The Damned One Hundred,” Jonathan Maberry asks a very old question: how much would someone give in order to save one’s people from destruction? The answer, in Maberry’s estimation, is simple: everything. This story opens with a father, Kellur, and his teenage son, Kan, standing at the gates of a cathedral inhabited by vampiric witches. Kellur and Kan arrive at this holy place about three days ahead of a Hakkian army which will, without doubt, destroy their homeland. Defender of the Faithful, Kellur, requests help in defending his people against the brutal onslaught of the Hakkians. He’s entering the church of the Red Religion, and he is willing to betray his own God to save his people. He is also willing to give up his own life to save his people. These two sacrifices I completely understand and agree would be made by someone protecting his homeland. The final sacrifice that Kellur is willing to make to protect his own people is his son. Few would sacrifice what Ernest Becker would call one’s own “immortality project” for a more abstract goal. I would have needed more in-depth characterization that allows me to see Kellur’s internal struggle to make this decision. It’s too easy. He asks the witches to turn him and his son into monsters. They will die horribly, but before they do, each will become as strong as fifty men. He also asks the witch to turn one hundred of his men into this kind of terrible creature so that they can destroy the Hakkian army. A fun story but one that presents too easy of a moral decision.

In “Blood, Ash, Braids,” Genevieve Valentine presents a tale of the members of the 588th, a World War II-era Soviet squadron consisting of female pilots who terrorize the Germans by flying biplanes, the engines of which they turn off as they make their bombing runs. The Germans call the female pilots witches because their planes with their silenced engines sound like brooms. All this would be interesting enough. But there’s a catch: one of the pilots is a real witch. This tale is fascinating. Most pilot stories—within the genre and without—concern male pilots. Many of these stories present bad boys, knights of the air, implacable commanders. These men—based on people like Manfred von Richthofen and Gregory Boyington—present the quintessential uber-masculine hero of the twentieth century—the pilot—as the descendent of the knight on horseback or, perhaps, in the case of Boyington—the pirate, a trickster figure. Valentine takes the pilot as trickster a step further by making the figure into a witch. In addition, this tale is welcome because it goes to a side of the war and a culture often ignored by writers about World War II: Russia. The war proved the most frightful here, not on the Western Front. But most American writers pretend that combat in Europe involved only England and the United States. So, this tale is welcome for that fact alone. But there’s another reason why the tale delights. This story concerns women: the pilot as witch, dropping curses on her enemy. We have friendships here, as we do in most tales of male fighter pilots, but these are softer friendships, often consummated over a bit of food—in this case, chocolate—rather than over the inevitable glass of scotch in the officers’ club. We also have the implacable commander here, and we learn her origin story. Ultimately, this story is less about warcraft or witchcraft than it is about friendship and dedication to one’s peers. Friendship in this tale also takes a supernatural turn when the witch places a spell of protection on her friends’ planes. We have the horrors of basic training, but they take a unique twist here: the shearing of braids. Finally, this tale is one of the best written I’ve seen in a very long time. The writing here, in parts, approaches that of Margaret Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale. And that’s a fitting comparison since the protagonist is kind of a witchy Offred, or maybe Moira. All in all, a very beautiful and lyrically written story.

“Mercenary’s Honor,” by Elizabeth Moon, is the first tale in the collection to give us something of war’s real and traditional nature, something the United States is finding difficult to stomach. To riff on and expand Clausewitz, war is always connected to politics and economics and serves those two primary ends. Unlike the case in World Wars I and II, war has usually been a half-way measure, not something that leads to complete devastation and destruction of one side and complete victory for the other. Moon also gives us something else that the tales so far have not: the seeing of one’s enemy as a person worthy of respect. While certainly, there is battle in this story, the tale really concerns relationships and the admiration of the good qualities of one’s enemy. This tale, in an age of popular culture that features Armageddon as the outcome of any battle and enemies that are completely inhuman, serves to remind us that war is ultimately about humanity. The story opens with the Ilanz Balentos becoming the Count of Margay, a small town in a medieval world. The captain of a mercenary company, Balentos is slowly going blind. Soon to be unable to roam the countryside, he signs a contract with the council of Margay. In return for the protection offered by his soldiers, Balentos will gain a home base. There is a complication, though. The Guild League could be playing groups of mercenaries off of each other, tricking them to fight each other to decrease the mercenaries’ power. Thus, in his new home, Ilanz soon discovers that a very formidable mercenary company, that of Halveric, is marching toward him. In a very humorous turn of events, Illanz allows himself to be captured by young Halveric squire named Kieri, who takes him to Halveric. Once together, the two commanders discuss the situation and work out a solution which will enable them to not destroy themselves. This tale concerns the war of city states or perhaps of corporations. I was very impressed by the human masculinity of the main characters and the way in which this story gave us something different in contrast to the all-or-nothing kinds of stakes usually presented in war stories.

“The Guns of the Wastes” by Django Wexler presents a very interesting world, one in which land ships sail and steam across wastelands and small dog-size robots attack like vermin or aliens. This is a steampunkish world, one that’s very compelling. The tale begins with Second Lieutenant Pahlu Venati being transferred from a cutter to a heavy cruiser in the Alliance Navy. Ships here sit on caterpillar tracks, which rumble the ships across the desert. There was a plague in earlier years, and the ships cruise past old cities filled with disease and waste. The second lieutenant’s job—in conjunction with that of the first lieutenant—is to take care of a scientist on board sent to discover and study the sraa, or scuttlers. The scientist gets exactly what she wants. The cruiser is stormed by thousands of sraa, little mechanical beasties. This was a very entertaining tale. The motif—the relentless assault by predators—be they zombies, orcs, or bugs—isn’t exactly new. But the steampunk setting makes this tale fun. I enjoyed it very much.

“The Graphology of Hemorrhage” by Yoon Ha Lee is one of the most interesting yet vexing tales in the collection. Tepwe Kodai is a calligrapher for an empire. More than that, she casts spells through her writing. When the story, told from the POV of Rao Nawong, a Lieutenant in the Imperial Army and the assistant to Kodai, opens, the two are on a hill while Kodai prepares to cast a spell which will destroy the Spiders, a faction, rebelling against the Empire. By the end of the tale, Kodai writes the spell into existence, but she also writes somebody out of existence. Most of this tale is told in back story. It’s not really a war story or military tale as much as it is a meditation on the power of writing and authorship, the relationship of the word to magic, and the ultimate documentary nature of empire. I can’t say that I was enthralled by either the characters or the plot, but I did enjoy the quietness of this tale, coming as it does in the middle of a cacophony of war.

In “American Golem,” Weston Ochse tells a delicious tale of magic, revenge, and justice of sorts set in the political junk pile that is American-occupied Afghanistan. A Jewish American solider, Isaac Drachman, died in Afghanistan, the victim of a militant bomber, Vor Gul. In the desert of New Mexico, Isaac’s grandfather, Emil, an Israeli probably involved with the Israeli Defense Forces, exacts revenge by constructing, with the help of an old Navajo woman, a golem. This creation, called Isaiah Drachman, goes to the Middle East in pursuit of the killer of his “brother.” There, unfortunately, he discovers that the politics of Afghanistan are horribly messy, with American intelligence officials being as cutthroat as the bad guys that they hunt. This story becomes a morality play about the ability and the desire to do the right thing in a political world in which right and wrong have become almost meaningless designators. This is the most ethically and politically sophisticated tale of the collection, which sometimes reduces war to an amoral chess game. I highly recommend this story.

In “Weapons in the Earth,” Myke Cole presents a story that is a combination of slave narrative and a prisoner-of-war or concentration-camp tale in which the protagonist finds the strength to fight back against oppression and save the people of his homeland. The catch is that the protagonist and the antagonists are goblins. Several Black Horn goblins—including Twig, Stump, Hatchet, White Ears, and Black Fly—are captured by Three Foots goblins, including the absolutely disgusting and sadistic Gibberer, who is at least half mad. Captured along with the Black Horns are their kine, cow-like creatures, which prove in the end to be anything but lowing bovines. The tale is set in the winter and feels a lot like a forced march on the Russian Front. The tale, which moves slowly at first, truly shows what it’s like to be taken prisoner: the despondency, the torture and death of beloved comrades, the collaboration of some prisoners with their guards, and the small rays of hope emanating from a child. While the tale crawls at first, readers are rewarded for their work in trudging through the snow by a long climax that is absolutely spectacular and of the very highest stakes. I truly enjoyed this story, which, at its core, is about a hero’s journey from uncertainty to self-actualization. And Cole’s work resonates on so many levels: the holocaust, slavery, and the taking of prisoners in the current Middle East.

“Heavy Sulfur” by Ari Marmell takes us to the Western Front in 1916, a few months after the Battle of the Somme. In this Great War, both the British and the Germans summon demons. In this case, Corporal Cleary, a magi himself, must go behind enemy lines because the Kaiser’s forces have summoned an entity that was also summoned by one of His Majesty’s Grand Magi. The entity, now with the Germans, must be banished or destroyed before the Boche discover its true nature. Unfortunately, although dressed in a German uniform and speaking fluently the language of his enemy, Corporal Cleary runs into problems in the enemy trenches and must enact Heavy Sulfur protocols. This tale was fun, but I didn’t at all like the ending, which seemed to a make a beginner’s mistake in terms of point of view.

In “Steel Ships,” Tanya Huff gives us a unique take on SEAL teams—their operatives are real seals, shapeshifters, that is. In this pre-industrial world, the Royal Navy’s Special Forces, under Commander NcTran, are tasked with destroying newly constructed steel ships of the Navreen. If the mission—involving both incendiary devices and cast spells—is successful, the High Command believes that the Navreen will sue for peace. Led by the shape shifter Kytlin, the Special Forces operatives travel by both schooner and flipper to their target, where they encounter their opposite numbers, wolves who function as archers in their human forms. This was a fun tale for me, perhaps because I like seals. Yet, I wasn’t overwhelmed by it, perhaps because I wanted more character growth and more battle.

In “Sealskin,” Carrie Vaughn presents one of the most entertaining stories of the collection. Richard—a Navy SEAL officer and sniper who was born with webbing between his toes and fingers—considers leaving the military because of a disaster he partially caused. A rescue of three hostages held by Somali pirates went very badly. Richard killed a fifteen-year-old pirate a few seconds too late. The pirates killed all the hostages. Needing relief, Richard flies to Ireland for a vacation. Richard’s mother, who has recently died of cancer, conceived her son while in Ireland. Oddly feeling drawn to the land of the father that he never met, Richard goes to a pub and is told some information that leads him closer to the land—or dare I say it, water—of a mysterious father, who had the genetics to produce a son with webbing and lungs strong enough to allow Richard to hold his breath underwater for up to ten minutes. I won’t give away the ending of this charming story, although I will say that I was reminded of the 1994 film The Secret of Roan Inish.

T.C. McCarthy, in “Pathfinder,” takes us to what, for Americans, is the other side of the forgotten Korean War. When the story opens, we find a Korean, Hae Jung, working in a hospital in Hamhung, Korea in 1951. A massive American bombardment is underway: bombs, artillery shells, and even naval artillery shells rock the town and the mountain fortress in which Hae Jung works as a nurse tending to wounded Chinese soldiers. In addition to her nursing duties, Hae Jung also works as a Pathfinder, a kind of spiritual medium, under the direction of the monk Dae Nam. Apparently, the Americans, through their bombardment, unleash a destructive spirit, one that rises from the dying body of a Chinese soldier and eventually enters the body of a little boy. This spirit is so powerful and capricious that it could turn on the British and the Americans. This wasn’t my favorite story in the anthology, but one line makes the tale provocative and memorable. A factory just about disintegrates under the American bombardment, and Hae Jung observes: “Americans have to hit it so many times, over and over again, and she marvels at the amount of equipment they have, wondering if it explains their willingness to summon a spirit so powerful and beyond control; they seem to worship destruction.” As an American, I’m used to cheering when American shells blow up the enemy in movies. But this line makes me pause and think: what would it be like to be on the receiving end of this kind of attack? And given that this story is set at the beginning of the nuclear era, when the United States did summon, in the form of the atomic bomb, a force “so powerful and beyond control,” the tale makes me wonder: does America worship destruction?

In “Bomber’s Moon,” Simon R. Green asks a very fun—and given the evil of the Nazis—a fairly morally plausible what if: what would have happened if the Nazis had, after D-Day, summoned the forces of Satan to fight on their side during World War II? The story, which chronicles Operation Shadrack, opens in a scene familiar to fans of movies about the RAF: at an airbase at night, just before a Hampden bomber piloted by a young officer, Rob Harding, is about to make a raid over Dresden. The catch? This possessed bomber has fuselage composed of Bible pages and will have as its ultimate navigator and counter measure the angel Uriel. Because Satan has intervened in the war, God does as well. Spitfires, men and women possessed by angels, will provide escort for the bomber. The crew of this Hampden consists of, besides Harding, Chalkie, James (the main gunner firing dum-dum rounds with crosses hatched in them), and David (the rear gunner, who operates a holy-water cannon), and a priest, Father John, who isn’t quite what he seems and suggests the character Frank January from Kim Stanley Robinson’s “The Lucky Strike.” This is a fun story. I have only one problem with it: the location of the raid, Dresden. This is a loaded name. The Allies, in the real World War II, set, in what was clearly a revenge raid, the air of the German city on fire. British and American bombers killed over a hundred thousand people as firestorms swept the city. In this tale, the Germans butcher their own people in Dresden. Thus, there seems something not quite right about setting a battle between good and evil over this city since it was clearly a site of Allied evil.

In “Bone Eaters: The Black Company on the Long Run,” Glen Cook presents a tale featuring a strong first-person narrative voice, Croaker’s, that is both sophisticated and world-weary. This tale, while certainly fantasy, presents a very realistic and perhaps unflattering picture of human nature and especially of youth. We begin the story with an attempted rape of a young female bandit prisoner, Chasing Midnight. She is a witch who ends up being a member of the Company for a while and helps deal with the menace presented by the Hungry Ghosts, vampire-like spirits who inhabit earthly creatures. This tale is very dark and stark in its presentation of human nature and motivations. It’s also very unflinching in its portrayal of women. This portrayal might bother some, but it will be welcomed by others. Cook’s is not the most fun tale in the collection, but it is well worth a read if for no other reason than its presentation of human character.

In “Skeleton Leaves,” Seanan McGuire gives us a dark Peter Pan story. With the original Pan long gone, one of his successors, a girl named Sheila, serves as a generation’s leader. War is on its way to Neverland about a hundred and fifty years after Peter Pan promised Neverland’s children that they would never grow up. Pirates are on the horizon. The war here is darker and bloodier than that of the movie versions of the Pan story. People don’t get bopped on the head or pushed in the butt over the side of a ship. They get stabbed in the throat and in the stomach. The Pan’s Wendy, the sister of this Pan, who helps to shepherd children into battle, is really jaded. She’s tired of the fighting. This Pan story haunts me because it serves as a metaphor for something much bigger and darker: young people being seduced into war. And perhaps the story functions as a metaphor for the endless war of the last ten years. Since many of the children of Neverland get kidnapped and serve as pirates, perhaps the story is a metaphor for all of the young people who get turned into terrorist operatives. This is a beautiful, heart-wrenching take on one of the seminal stories of the last century. No Disney or Tinkerbell here.

In “The Way Home,” Linda Nagata delivers a tale of a contemporary army squad somewhere in the desert of Afghanistan or Iraq. Led by Lieutenant Matt Whitebird, who has had very strange premonitions, the squad is returning to its outpost after hunting down insurgents. A missile hits a bit a hill “made of ancient, weathered, rotten stone,” and the squad finds itself in a desert with no life except for demons who progressively use more sophisticated weapons against the soldiers. While the squad members are terrified, they discover a way home. Whenever they kill a demon, a door between dimensions opens, and a human can pass through. They also discover, through a friendly-fire incident, that when they kill one of their own, the door also opens. This tale is lean and not really full of any wider significance. It’s just a solid tale. And I appreciated this solidity.