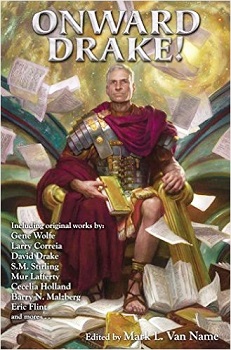

edited by

Mark L. Van Name

(Baen, October 2015, 272 pp., hc)

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

Editor Mark L. Van Name organized Onward, Drake! to honor the now-seventy longtime author David Drake, whose dozens of books and more than a hundred short stories embrace fantasy, science fiction, horror, and comedy. Fourteen authors contributed fifteen original stories to the anthology. David Drake outwrote his colleagues, contributing two pieces himself–including one from the universe of his well-known Hammer’s Slammers series. Drake also contributed essays about his story-writing that may appeal to those with an interest in writing as a craft, while explaining a little about his background and process that may help those who read his other stories. Indeed, each piece includes an afterward by the author. Most explain the author’s connection to David Drake, the story’s connection to David Drake, or both. Particularly as a collection, these afterwords offer readers perspective on Drake–the value of which one can see even from the two Drake contributions to this very volume. Readers new to Drake will find the perspective(s) useful in assessing whether they should take more interest in Drake’s work.

Drake’s larger body of work aside, this anthology’s fifteen original pieces offer a range sure to reach readers. Sarah Van Name and Sarah A. Hoyt both insert David Drake himself into their stories–and because both stories depict him as having an awful sense of direction, one’s tempted to suspect the portraits of Drake are accurate in other areas of agreement as well. Drake himself opens the anthology with a humorous piece, but grimmer works by Mark L. Van Name and David Drake help sketch a broad range of stories about conflicts and what they do to their survivors. Hank Davis mates a Lovecraftian horror finale to a modern-day-feeling near-future piece set on a military base, but delivers character color and efficient descriptions one could search a long time without finding in the works of Lovecraft himself. But it’s not all modern and futuristic settings: Drake’s first piece is set in a fantasy Rome and others include historical settings as the sole backdrop or through time travel. Anyone with an interest in David Drake or military fiction generally will enjoy Onward, Drake!

David Drake’s “The Great Wizard, Cabbage” follows a credulous twelve-year-old wizard through a fantasy Rome in which his uncle pretends the power to perform magic in a moth-eaten robe while struggling to put on airs of gentility for marketing purposes. A doorless dwelling and uncertain prospects for dinner put the protagonist in a dingy and dismal and very traditional spot for the start of a fantasy adventure while poking fun at the fake wizardry of his powerless uncle. But the protagonist’s huckster uncle doesn’t prove the world’s without magic: Cabbage no sooner steps from home on an errand than he crosses an honest-to-goodness blue-spark-throwing wizard with a real cape and everything. Guileless fool protagonist, mistaken identity, class conflict–what’s not to love? Drake’s first entry in this volume is a lighthearted, entertaining fantasy.

Gene Wolfe’s “Incubator” opens on a seemingly technological mystery in an SF world that proves more Weird than SF. The first characters that appear in the story each present with a specific, traditional, binary gender; however, the third is a door that speaks and the fourth has the gender-pronoun ze—which might seem more forward-thinking if the character weren’t described using terminology currently in use only in the adult entertainment industry, and offensive to those described by it in other contexts. The alien environment is interesting, and part of the piece’s point seems to be to force readers to share the protagonist’s puzzlement with her surroundings. The puzzle gets less clear as the piece progresses; the narrator is treated to a discussion about the nature of observation (e.g., one doesn’t observe reality, one infers it from stimuli) in time to confront blatant factual inconsistencies, and suffers puzzling uncertainties that cloud conversation until something drives her to flight. If you require stories to offer a protagonist with clear goals confronting opposition that forces a character-defining climactic decision, this may not be for you–but if you like weird tales, this one’s for you.

Eric Flint’s “Flat Affect” is a third-person tale set in a monarchy ruled by a profligate and whimsical King. The King’s opening demand for a season of revelry to celebrate a tradition with which none were familiar, coupled with his demand for purpose-built outdoor stadiums and the importation of musical talent, stand at odds with his preference for a performer who appeals primarily to dour veterans by delivering gruesomely accurate accounts of battles with a flat affect, unadorned by artistic embellishment. The climax doesn’t involve the King’s story-opening conflict with his Chancellor of the Exchequer or the consequences of the King’s decision to pour the public fisc into entertainments, but instead turns on onlookers’ reaction to a eulogy delivered by the King’s favored bard. Consequently, the strength of the work turns on the reader’s reaction to its mood rather than to its structure. Based on the author’s afterword, it appears to be an allegory for the author’s relationship with David Drake. Self-referentially, the story is filled with characters who appreciate art they don’t care to explain to outsiders. Flint’s piece is aimed at people who feel like Flint do about his subject, and those people will particularly enjoy a work made just for them.

Cecelia Holland’s medieval-feeling “Sum” follows an officer in something like the City Guard on a mission to arrest a spy on an informant’s tip. The title is not about mathematical operators, but is a Latin reference to Descarte’s first-written-in-French argument “I think therefore I am” in his work Discourse on the Method. Philosophical arguments frame a conflict between the narrator and physical obstacles (or arguably the protagonist’s self). This story is not for readers who only believe in conflict that involves an antagonist against whose will the narrator must contend. This is a struggle-to-survive narrative; once it gets moving, it follows the narrator’s progress toward freedom. Holland’s afterward suggests the piece may have a selective intended audience, as it was written for Drake in part “because I know he will get all the jokes.” Drake fans may like the story to test their ability to get Drake-aimed jokes.

Mur Lafferty’s “The Crate Warrior, the Doppelgänger, and the Idea Woman” is a fantasy that opens in a film studio’s backstage break room. The worldbuilding on display in this piece exposes a hilarious universe not easily imagined from the open. Who would have imagined that faeries would have a film industry, too? And, one that would need tiny food props? And that faeries would have tiny winged outlaws? The story delivers classic fairy tale elements: a royal wedding, a deadly secret, and a fairy bargain that goes … well, if it went as hoped it would hardly be a fairy tale, would it? Lafferty’s is a fun piece, worth reading, and the most enjoyable harbinger of terrible, terrible war you’ll read all year. Enjoy it before the faerie invasion because after, well ….

Tony Daniel’s “Hell Hounds” opens on a down note: the narrator’s discovery of his own mother’s corpse lying eaten in a pen with three rescue dogs. The reader sees no fantasy elements until Daniel establishes the glum mood and the narrator’s disinterest in the fantasy aspect of his world. Once we see the narrator’s magic, the hook is set: how can he resist embracing his powers? The path to the narrator’s destiny lies decorated with horror elements. The narrator’s disconnection from his family gives the plot its shape as he reconnects emotionally to his family and undertakes to use his powers to solve a problem he learns–late–to be intertwined with his family history. To see a loner finally connecting, and an isolated adult feel part of a family, might feel heartwarming–but the ick factor in the horror elements derails the feeling before happy-warm-feelings gain much momentum.

Full-color characters and a gritty mood lay a strong foundation for a grim victory. The climax of “Hell Hounds” meets the expectation built in the story’s rising action, and the resolution brings the end together with the opening and backstory in a satisfying revelation to the narrator–and the reader– regarding his family and his place in it. The author’s note offers a colorful story about Daniel’s connection to Drake and the inspirations for the characters around which he crafted “Hell Hounds”–a fun bit worth reading if you’ve ever wondered where authors actually find their story ideas.

John Lambshead’s “Technical Advantage” opens on a jungle, Fighters following their Leader to advance against their Enemy. We don’t know what the Enemy’s objective is–or, for that matter, the Fighters’ objective (or the Leader’s). The high-risk world kills most of them on missions like theirs, but since it’s not clear why anyone is there the larger stakes remain a mystery. It’s hard to get behind a story without an interesting character or a compelling objective. The characters’ generic titles–Leader, Enemy, Technician–feel like masks that prevent one from discerning anything specific about the people who wear them. In another setting they might give an archetypical, larger-than-life feel to the actors … but with no clue about the characters’ motivations or objectives they feel like yet another obstacle, standing between the reader and the sense of flavor one often gets in military fiction as one encounters ranks, titles, and forms of address that give a feel for the group’s culture and show how the characters relate to one another. Contrasting this with Drake’s final piece in this anthology, Drake offers a human-feeling protagonist with specific anxieties and identified expectations: we know who Drake’s protagonist is, what she values, and why those about her follow her instructions.

Lambshead’s afterword suggests the story’s “flat emotionless style” conveys combat-zone mental processes. Flat emotionless style needn’t prevent readers’ discovering a unit’s objective or even the impact of the war on the larger world, or on the characters themselves. Onstage characters appear to have no connection between them, and little to offstage events sketched only enough to show an ongoing war. Emotional engagement with the Leader’s efforts or his followers’ sacrifices is hard without more. Readers who want to see a climax put the protagonist to a character-proving hard choice may have difficulty with the piece: the Leader’s emotional disengagement from those he directs make his sacrifices of their lives feel too easy to serve as the hard choice. Since we have no clue what the Leader values, or what’s at stake in the war (besides lives he has no hesitation or regret as he spends), it’s hard to tell whether his successes should be cheered or booed. Emotionally vacuous characters can feature large in a gripping tale, of course. A glance at the 1978 Star Wars or the first Terminator film shows implacable mechanical killers advancing while audiences knuckles go white with fear and anticipation–pure gold. Soulless characters thrive also in fantasy: Rowling’s Voldemort is no machine, but he’s heartless. Yet these stories don’t stand large in our collective consciousness because the public loves soulless characters bent on body count (which any low-budget slasher flick would deliver), but because audiences connect so well with foreground characters who feel and fear and dream about a future–characters with loved ones to lose, hopes to dash, and causes we’d hate to see fail. To hide characters’ goals from the readers prevents emotional engagement with their objectives, and prevents readers from being able to tell who’s winning. Inability to get behind a purpose and ignorance whether it’s succeeding add to concealment of the characters’ feelings about their surroundings to thwart engagement. “Technical Advantage” requires fans seeking a purely-physical conflict.

Yet, “Technical Advantage” faces an additional challenge. Beneath its action lies cultural framing that gives a dated feel at odds with the dim-future world in which it’s set. From Molly Millions in Gibson’s 1981 “Johnny Mnemonic” and the killer replicants in Ridley Scott’s 1982 Blade Runner, the dim future has always been shaped by tough women. Women–whether Boudicca leading an army to raze Roman cities in Britannia, or nameless women feigning maleness to avoid splitting their families in wartime–have fought in every war I’ve studied. And no, Boudicca isn’t some kind of rare Celtic anomaly unreplicated in history; Ching Shih may be the most formidable pirate admiral–male or female–the world ever saw. This is not to say a story must make a point of identifying its participants’ genders (if any). Unfortunately, “Technical Advantage” draws such focus on tough warrior men herding doe-like “girl” porters through a war zone that it lays a dated fantasy-medieval patina over what should feel like a grim future conflict (involving ‘mekanoids’ and the high-tech enemies who operate them). An attractive feature of military fiction is unit culture, the credibility of which is essential to reader belief in warriors’ willingness to advance against opposition and to sacrifice for their common objective. When “Technical Advantage” shows mekanoid attacks that turn unskilled expendable “girls” into cannon fodder turn out to be part of the warrior-men’s plan to consume enemy resources against low-value targets, we’re left to speculate what could possibly motivate anyone in their company. And the useless-women view of the characters isn’t limited to one actor; the protagonists’ mission planners assume it, too. And not just the protagonists. The only female character with any dialogue is a fool who opens a door to an expired entry code, then freezes when she realizes she’s under attack. Among a throng of soft enemies, there is but one competent opponent–a man. The message seems at odds with what readers know from their own world, which has had warrior women as long as it’s had war; even America’s military finally recognized women can train for and perform combat roles, more than two centuries after Mary “Molly Pitcher” Hayes supported the Continental Army’s artillery efforts at Valley Forge. It seems an unnecessary distraction in a futuristic story to provide so much word count emphasizing hard-cast gender roles molded from an age that otherwise exists only in the faux-medieval worlds of old high-fantasy novels. The intended message of “Technical Advantage”–that war is more about people than their tools–feels lost in a story full of distractions, and whose actors’ motivations and objectives remain completely hidden from the reader throughout the piece.

T. C. McCarthy’s “Saracens” opens on a besieged city in a fantasy medieval Europe, in which an aging and disgraced priest follows divine visions in hope of infiltrating an enemy camp and defeating the sorcerer responsible for their enemies’ advance. Conflict with his angry brother gives perspective to the conflict and a human feel to the characters while providing the reader a strong sense of setting. The protagonist’s physical infirmity emphasizes that his only strength lies in his divine favor–if it isn’t a delusion. Advancing with his brother against their enemies’ whole armies gives an opportunity for the protagonist to reflect: the unfairness of the world, the misery of his lot, the certainty that some of the enemy must be good at heart. Time crawls during the advance, but not to the story’s detriment: the stakes become clearer; characters’ contemplation of the nearing dangers and their overwhelming odds build tension. The conflict itself appears mostly a test of faith–of conviction in the face of mental opposition. The climax combines the physical threat of soldiers (against which his brother offers defense) with the spiritual threat of the supernatural force that stands behind the advance against the protagonists. Fittingly for a fantasy about a defrocked priest, faith rather than force of arms wins the day. Yet, it’s a military fantasy: without faith his brother will protect his back, the protagonist would be helpless to prevail. The author’s afterword suggests the story is inspired in part by current events; in that light, the story seems to urge readers to look in particular at the protagonist’s lost status, the harm his selfishness has done to those who depended on him, the doubt that’s grown among his allies–and urges readers to conclude that even fallen and seemingly unfit folk can overcome infirmity and fear to act, undermine the evil forces that send enemies against them, and to restore the faith of their companions.

When Eric S. Brown’s “The One That Got Away” opens it’s not immediately clear whether the horror story describes an ex-officer with PTSD nightmares after surviving a multiple-murder during a death notification gone bad, or an urban fantasy about a man hunted in his dreams by a supernatural killer. The adjusting-to-civilian-life aspect of the tale comes through the same either way: answering to a younger, inexperienced employer who continually passes judgment on the quality of unskilled labor and who gives uninvited instruction about off-hours drinking comes hard to an officer used to command. In Captain Richmond’s case, it’s not a particularly successful transition. Backstory reveals the supernatural threat’s nature (and how Richmond got drummed out of the military), and when the climax comes Captain Richmond’s alternatives are clear: to cower as always before, or–finally, though perhaps futilely–to resist. It’s a horror short you know can’t come to any good–and perfect. Enjoy it.

To critique Barry N. Malzberg’s “Swimming from Joe” as a short story immediately thrusts one into the major challenge Robert McKee would characterize the short work’s structure as representing anti-story: it doesn’t relate a logical series of connected events, but sketches a spiritual comparison between a celebrated actress and a veteran combat unit. The piece suggests meaning–perhaps martyrdom and veneration, perhaps a comment on surviving the horrors inflicted by an uncaring world–shared between the soldiers and the actress. It comes off reverential and contemplative. To discuss its interpretation would be like discussing a poem or a painting; it may criticize outsiders’ shallow view of their subject and their postmortem veneration, but it does more and one best feels these things out for one’s self.

Sarah Van Name’s “The Village of Yesteryear” is a fictitious autobiographical account of the North Carolina State Fair the day the carousel sent the author so far into the future the ride stood in the Village of Yesteryear. This much is fun. There’s a brief feeling the tale drags when the narrator relies on her father’s friend Dave–the author Tuckerizes David Drake and his wife Jo into the story as her parents’ friends, who in real life they are–to explain things ‘to the narrator’ (read: to the reader). There’s a lot the narrator could conclude by herself just fine, that feels heavy delivered in dialogue. That said, it is a funny story: Dave’s foul language (despite the presence of a minor) when he realizes they’re screwed, the “amazing” things that impress alien citizens of future-Earth, the inevitability fact that state-fair hucksters used to defrauding rubes from their own time will have no trouble scamming hicks from a prior century, the certainty that the narrator will end up in a sideshow herself if she’s not careful–it builds and builds. The unlikely escape puts an entertaining fantasy cap on the tale–which, from the beginning, we know none believe but Dave. A good laugh.

An Army sergeant narrates Hank Davis’ “The Trouble with Telepaths” in a United States that imposes compulsory service on telepaths and makes them officers (the first problem with telepaths, according to the sergeant). A complete non-telepath himself, he has no idea what kind of day awaits him when he gets orders that lead to a meeting with a high-ranking telepath. But there’s something odd about him–and the telepaths who have plans for the military need to make sure he won’t cause them problems. The twists reveal and sketch a dark horror universe in which the narrator is carefully kept oblivious of the real danger surrounding him. The end beautifully caps the dark world Davis so deftly crafts. The afterward sounds like Davis worries his story won’t stand up to comparison with his pro peers–but he’s got nothing to worry about. “The Trouble with Telepaths” is a beautiful horror story to which a more perfect conclusion could not be crafted. A work of art. More detail risks spoilers–and since you want to read it, I won’t do that to you. Of course you do. That’s why you’ve just bought a copy for your friend, then forgotten it, so you can buy another copy again for the first time and enjoy it all over again… and again….

“A Cog in Time” by Sarah A. Hoyt Tuckerizes David Drake into a time-travel fantasy as an officer in the Time Guardians. In honor of Drake, Hoyt presents an action-packed race to stop (yet another) assault on Shakespeare at The Globe. In the best tradition of Kirk violating the Prime Directive at the drop of a hat, Drake’s immediate response to the unfolding disaster is an intervention so dangerous the Time Guardians had more regulations against it than anything else. Not that Drake was rogue–no, no –because Drake had the authority to do it anyway. Hoyt drops entertaining references to Monty Python, period trivia about Elizabethan England, and obscure barely-recognizable languages like early-modern twenty-first century English. It’s a comic piece celebrating Drake the Time Guardian, and plenty of fun.

Mark L. Van Name’s near-future “All That’s Left” follows a former enlisted man septuagenarian after he’s been persuaded by his husband to meet an officer about a new Army intervention to address post-combat stress and its attendant nightmares. The officer’s pitch sounds suited to encourage entry into a traditional therapy such as counseling or oral medications, but the new cure for veterans’ post-combat stress turns out to be memory erasure. The officer presents the soon-to-be-approved-by-the-FDA technique as effective to restore restful sleep to combat veterans. The piece’s greatest strength is the protagonist’s inner dialogue, which quickly and clearly exposes who Crane really is by showing the harsh difference between what he feels and what he’s willing to express–sometimes with a harsh light on what he’d like to do but doesn’t. His rage at the audacity of those who weren’t in combat telling him how his life could be improved is countered by his commitment to his husband, who’s been at his side fifty-two years and patiently endured decades of disturbed sleep and nightmares and who deserves better in his last years if it can be delivered. While he’d never seek the treatment himself … he’s loathe to deny his husband. The details–the treatment tech’s comments contrasted with the overconfident proclamations of the Army physician–give a real feel for Crane’s relationship with the Army. Despite halting nightmares, the science-fiction PTSD therapy turns out to have some serious shortcomings. Some reversals–mostly addressing Crane’s relationship with himself and those he means to live with the rest of his life–lead to a satisfying resolution that calls to mind the poem by Stephen Crane:

In the desert

A military short by Larry Correia, “The Losing Side” is set in the universe of Drake’s Hammer’s Slammers and told from the perspective of a soldier against whom the Slammers had been hired to fight. Gallows humor helps give a realistic feel to soldiers’ dialogue as they try to avoid destruction by better-armed enemies. “The Losing Side” squarely addresses the grim truth that truth and justice mean less to battle outcomes than preparedness: competence, sure, but also materiel. “The Losing Side” celebrates the badass mercenaries of Hammer’s Slammers, but its grim portrayal of mere heroism as insufficient to achieve victory is capped by a start-of-a-new-war conclusion which feels like a high note–it promises a better future by reflecting the wisdom gained from prior defeat. It’s a suitable conclusion for a Slammers story, crafted by an enthusiast for the series. Fans of Hammer’s Slammers will enjoy seeing them in action from the other side.

Closing the anthology, David Drake’s “Save What You Can” is an SF adventure that opens on space troopers disembarking for infantry work in the tradition of Heinlein. It turns out to be a Hammer’s Slammers tale focused on advance troops who land in advance of the heavy gear. Grim pre-operations conversations reveal soldiers’ dark outlook on their new assignment–and the ever-present risk their new acquaintances won’t live long enough to learn their names. When the advance troops learn the heavy vehicles won’t arrive for a day (or maybe a month), they get orders to defend the spaceport against local hostiles by concealing themselves in unarmored outbuildings while shivering in a snowfall. While waiting for the delayed support element, the protagonist’s gritty world puts her through realistic-feeling equipment issues, unit transfers, unforeseen issues with civilians in the combat zone, and–of course–actual enemy attacks. The story draws attention to the random elements that guide individuals’ fates: skill has no impact on the risk from un-aimed fire, for example. The you-can’t-save-everyone aspect of the story shows up in characters that, in another tale, would be stock characters that prove the protagonists’ humanity. But this tale wasn’t crafted to prove soldiers are saints, or even lesser miracle-workers. They’re human, and that means they have limits. Grisly little details don’t overwhelm the story, but they paint the setting and color the characters. Readers who don’t know the Hammer’s Slammers series may want to try it out in this short, and learn about the world it portrays: a zoomed-in, tactical view of a war zone during an assault, an SF world with a gritty feel reminiscent of the future scenes from Terminator. The resolution fits Drake’s setting: survival is the main metric for success, and everything else is bonus.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

Onward, Drake!

Onward, Drake!