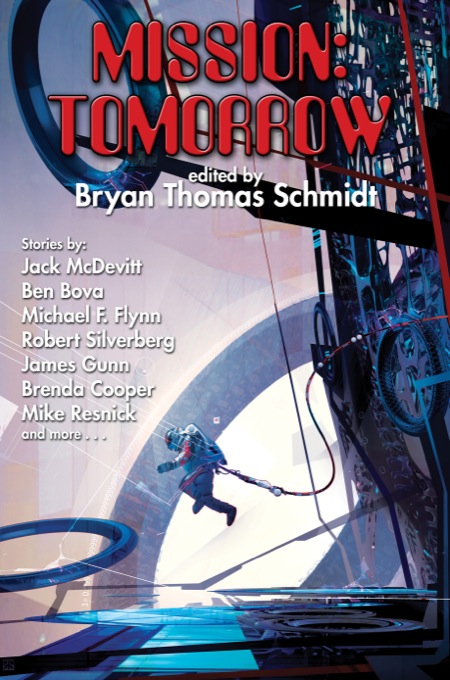

edited by

Bryan Thomas Schmidt

(Baen, November 2015, 336 pp., Tpb)

Reviewed by Rick Cartwright

We read interviews of individuals advocating the “one-way trip” idea of colonization where the would be explorers go to a new planet knowing that there is no way back. Mars is the current media darling. Robin Wayne Bailey sneers at such plebian undertakings in “Tombaugh Station,” placing his protagonist on Pluto commanding a mission to create the world’s largest telescope so powerful as to “see the face of God.” The story revolves around the investigation of the death of the telescope project manager and is not so much a whodunit as a well done examination of the consequences of extreme isolation and the toll it can claim on even the most dedicated people. The story is also a nod and a smile to the late Wilson (Bob) Tucker’s 1960 F&SF novella (expanded into the 1960 novel, To the Tombaugh Station).

Jack McDevitt cuts against the grain of the other stories of the anthology in that all the action in “Excalibur” takes place on Earth and the vast majority of the tale occurs in an office. Don’t think for a minute that lessens the impact. McDevitt weaves a tight, scarily plausible story that starts depressing and ends on a triumphant note you are never quite sure will be played till the very end.

Any student of the history of the Russian space program knows that much of its progress was lubricated by death. From Laika the Russian dog, sacrificed on the altar of “we got there first” to the ill-fated Soyuz 11 mission, the program has had more than its share of fatal accidents. However, unlike some other programs, the Russian space program has continued. In “The Race for Arcadia” Alex Shvartsman melds the Russian historical proclivity to “get there first” by cutting corners to the notion of sending a terminally ill scientist to a new planet. Arguably one of only a few stories that reached beyond the Solar System, a mathematics professor is offered the chance to be the first man to set foot on a new planet in a new solar system. Of course, the only way he can get back is the kindness of the competing nations to give him a lift home. Oh, and did I mention he is terminally ill? Despite the dark overtones, Mr. Shvartsman both puts a humorous twist on the situation and leaves you with hope for the outcome.

A “Walkabout” is defined by Wikipedia as “…a rite of passage during which Indigenous male Australians would undergo a journey during adolescence, typically ages 10 to 16,[1] and live in the wilderness for a period as long as six months to make the spiritual and traditional transition into manhood.” In “A Walkabout Amongst The Stars,” Lezli Robyn places her hero Tyrille Smith, the first Aboriginal Australian astronaut beyond the solar system, chasing down the mystery of why Voyager 1 suddenly started working again, including the packages that never worked to start with. This a dark first contact story with a twist at the end that was frankly a bit unsatisfying.

I have been a fan of Michael F. Flynn for years and he does not disappoint with “In Panic Town, on the Backward Moon.” Flynn tackles one of the most difficult missions of an SF writer, crafting a murder mystery without resorting to a deus ex machina or other macguffin. Larry Niven did this effectively with his Gil, “The ARM” character and Flynn continues the tradition with what starts out as a search for a missing package starting on the moons of Mars, and leads to the surface and murder.

Fans of the American TV show The Amazing Race will delight in this humorous tale of future reality TV run amok in “The Ultimate Space Race” by Jaleta Clegg. Somewhat reminiscent of the CM Kornbluth classics, “The Marching Morons” and its description of a dominant game show used to influence the masses, and the advertising driven society of The Space Merchants, Ms. Clegg proposes the most humorous and scarily likely solution to the funding problems of space exploration via advertising.

Set in the sky of Jupiter, Christopher McKitterick sets corporate pragmatism against academic idealism while examining the mystery of an organic world mind broadcasting a message that turns out to be something entirely unexpected from what it was originally thought to be. This is a story that foreshadows a preachy denunciation of corporate exploitation, but twists in a way that not only leads to a satisfying ending but leads to a fresh appreciation of technology.

“Around the NEO in 80 Days” is an outer space riff by Jay Werkheiser on the Jules Verne novel Around the World in 80 Days. A bet is riding on Mr. Phil Foggerty being able to make a round trip to a Near Earth Object and return in 80 days. Unlike the original, the betting partners are by no means English gentlemen. The science is more interesting than the storyline, although Mr. Werkheiser did the best any writer could do with the constraints of his premise. The author was wise to focus on the start of the journey and the obstacles to be overcome to get the trip started.

Brenda Cooper’s “Iron Pegasus” takes its inspiration from the Isaac Asimov robot tales, skillfully weaving in the facts the reader needs to know about the robots of her universe, with the story of an asteroid miner and her partner responding to a distress call that turns out to be tragically complicated. This was one of the best stories of the anthology, in that it was not only one of the best portrayals of robot characters that I have read in quite some time, but that it addressed how being isolated in space can bring out the best and worst in people, along with some solutions.

The legal status of claiming ownership of space resources is murky at best, as Michael Capobianco’s “Airtight” discovers, especially when the entity you’re negotiating with can turn off things in your spacecraft. The only real criticism I have is that the lawyers are reduced to bad stereotypes, which made the story a little problematic. Mr. Capobianco redeems that by having our hero lawyered up before he left. If you like poker, you will like this story. If you’re looking for a lot of action, you might want to give it a pass.

Angus McIntyre explores the rescue of an astronaut stranded on a damaged aerial habitat sinking ever closer to the hellish surface of Venus and the efforts to rescue him in “Windshear.” The story is fast paced with good characterization but, like too many of the stories of the collection, this story embraces the “soulless, evil corporation” trope. While it is true that corporations are there to make a buck and that is not likely to change as they move into space, the level of corporate disregard for human life in this story is simply beyond belief. Space industry is going to have peril and people are going to die in accidents. However, any industry that relies on humans is going to do its best to take care of them. Otherwise no one will want to work for them. Witness the efforts to rescue workers trapped in mines or sinking ships. That major issue aside, it’s a good rescue story and worth a read.

In “On Edge,” Sarah A. Hoyt explores how a trio of scientists looking for “A,” a faster way to deliver Amazon packages, leads to a completely unexpected “B” that is completely past the grant parameters. Along the way Ms. Hoyt explores the idea of individual ingenuity and humanity’s propensity to make great discoveries through crazy actions that people took for the best of reasons, though completely unconnected to the outcome.

Mike Resnick’s contribution to Mission: Tomorrow is “Tartaros,” a decidedly odd story and without doubt the wild card of the collection. If you are looking for a story of space manufacturing, mining, or exploration, move on. “Tartaros” is none of those things. In fact, it’s a story of a person finding their very specialized niche in the universe, where the notion of “one man’s heaven is another man’s hell” has a unique lease.

Telepresence, remote control of machinery, has often been described as a way for humans to exploit space without the added expense and resources of boosting life support for onsite astronauts. David D. Levine starts with that idea in “MALF” and runs with it, skillfully weaving in not only a very plausible scenario as to how a space mining operation could be set up, but the pitfalls of operating increasingly obsolete equipment over the long term. Mr. Levine’s hero battles a hacker with some help from an unlikely source for control of a valuable cargo that has the potential to wipe out some major cities if he loses.

Space elevators are often cited as a way to escape the gravity well of Earth, and Curtis C. Chen explores the ramifications and dangers of that mode of transport in “Ten Days Up” with a crew member stuck outside the ascending craft, her partner ill and unconscious and a lethal solar storm incoming. In addition to the physical dangers, our hero has to contend with a corporate bureaucracy more interested in process than saving her life. This s a good story and while it loses a little by relying on the “heartless corporation” as an antagonist, the well written action makes up for the loss.

I grew up on the stories of Ben Bova. Perhaps that makes me biased, but “Rare (Off) Earth Elements” is the jewel of the anthology. Dusting off his iconic Sam Gunn character, Mr. Bova tells the tale of a young taikonaut out to claim an asteroid for China only to find Sam there first. Except he has a little problem, the solution of which works out well for everyone involved.

Jack Skillingstead opens “Tribute” with a tragedy that destroys NASA and exploration. It doesn’t get better as Mr. Skillingstead chronicles the efforts of the sister of a fallen astronaut to return to Mars with the help of the heir to the only spacefaring private company left, a very thinly disguised Virgin Galactic. I tried to like this story. The ending is upbeat, redeeming some of the downbeat portrayal of an America that by and large had turned its back on exploration. However, the idea that private industry would have no interest in space except for tourism snapped my suspension of disbelief past the breaking point, particularly when the story alluded to other nations, especially the Chinese, that were pursuing manned exploration.

Mission: Tomorrow

Mission: Tomorrow