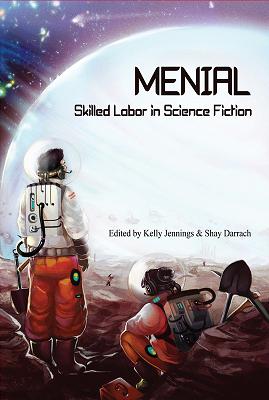

Menial: Skilled Labor in Science Fiction

Menial: Skilled Labor in Science Fiction

edited by Kelly Jennings and Shay Darrach

(Crossed Genres Publication, January 2013)

“Thirty-Four Dollars” by M. Bennardo

Reviewed by Chuck Rothman

Menial: Skilled Labor in Science Fiction explores an area of the genre that it often overlooked: the people who work behind the scenes, often in lousy jobs, to keep an imagined future society running. The eBook (there is a print edition as well) gives 17 variations on the theme.

“Diamond in the Rough” starts out as menial as you can get, with Magpie Dawson working in the waste recovery area of a spaceship, where he occasionally picks up some valuables among all the waste. He runs into Dusty Fuetz, a woman who is tossed down the garbage chute in a fight. They become friends, and Magpie ends up in a virtual reality fight to prove it. A. J. Fitzwater creates a couple of interesting characters, but the motivation of the others in the story is a bit vague, and it climaxes in a fight scene, something I’m not too fond of.

M. Bennardo writes about a world that’s undergone a major upheaval, with the protagonist working along Hudson’s Bay in the Great Canadian Desert, gathering wind power. “Thirty-Four Dollars” has the narrator talking about Gates, his partner who died during the year, and who left the $34 to him in his will. It’s a story about the setting and the changes and how the narrator reacts to the death of his partner, but I found it to be lacking in drama.

Sean Jones shows another dystopia in “A Tale of a Fast Horse,” where Courtney Alexa Fast-Horse starts out on the run in her craft — sort of a flying motorcycle — and is soon shot down to crash. She meets up with Tom, who helps her out and works to replace the broken craft. Tom is a whiz with the craft and the story recounts how he builds a new one. It shows a Native American perspective (and not the usual mystical one), but the story glosses over things, sluffs off some opportunities, and ends with everything in the air. You sense Courtney is looking for revenge, but it’s not resolved and the lack of confrontation leaves the story feeling unfinished.

“The Didibug Pin” is a revelation story — one where the entire plot is to reveal some secret. Lize works on an alien world, harvesting cliffcrawlers, small venomous animals, for shipment offworld. The pin in the title is that of a native insect, unimportant in itself, but a memory of a time when Lize met up with a woman at the fair who sold it to her and started telling her an important revelation. She is interrupted before she finishes, and Lize wonders what she had to say. Barbara Krasnoff paints a nice image of a company town of the future, but it’s a complicated conceit that doesn’t make much economic sense. I also was disappointed in the ending, which doesn’t really resolve the issues involved.

Jo is in love with “Sarah 87,” a type of sex android used to collect human sperm and send it to an alien race. When the use of these is banned, Jo has to keep Sarah from being discarded. It’s a clever setup, but Camille Alexa‘s love story doesn’t really catch fire.

“Carnovores” introduces Simon, who is moving to Callisto to help with the fisheries there. Creatures called Cherry-noses, similar to shrimp, are being harvested to feed humans. Simon has a secret that he doesn’t want to reveal and soon discovers an affinity for the Cherry-noses, who are not what people think they are. I liked Simon as a character very much and the situation was very interesting, but I wish the ending of A. D. Spencer‘s story would have reached a clearer resolution.

Andrew C. Releford contributes “Urban Renewal,” about the life of Alex, a college student and an Unusual, which is a man-animal hybrid similar to Cordwainer Smith’s Underpeople. Alex is constantly faced with prejudice, but just wants to move past it and get his degree. It’s something of a slice-of-life story but, like a lot of other stories in the anthology, gives the character a choice without showing him following through on it.

“Storage” by Matthew Cherry is set on a supply ship on a voyage to a Mars colony. Spell loses his clipboard while going through his rounds and discovers a mystery in the hold. I don’t feel the resolution is particularly clear.

“Snowball the Rabbit was Dead” and Lucky — an India-American high schooler feels responsible and wants to bury him. But the new employee at their family restaurant, an illegal alien of the science fiction kind, won’t let her. It’s an emotional tale that says much about life and death and global warning. I liked Angeli Primlani‘s way with creating characters that have some good depth.

Frank is celebrating his 45th birthday, depressed about his job and his life in general with “Leviathan” by Jasmine M. Templet. But even in the dystopia he lives in, his job — though menial and difficult — is absolutely vital. The concept is handled very well; though this is primarily a revelation story, the revelation is so wonderfully strange that the story is one of the best in the book.

I especially liked Margaret M. Gilma‘s “All in a Day’s Work,” set in a world with a hydrocarbon atmosphere where all humans are forced to live in a dome. Careen, Elena, and Tess run a small firm that has the contract to repair cracks in the dome and are out working when disaster strikes. The three women are well drawn characters and their concerns are very real to anyone working on the edge.

“The Belt” is an exercise in pure story adrenaline by Kevin Bennett. It’s set on Titan, where Javier falls onto a high-speed belt that ships ore at 60 miles per hour to a processing facility. There is no way off, and he faces certain death when he reaches the end. His brother Chavez jumps into action and races to rescue him. It’s a thrilling rescue that pulls you from start to finish, and the final line is a perfect summary of the philosophy of many of the stories in the book.

Jude-Marie Green‘s “Far, Far from Land” is The Deadliest Catch transferred to space. Instead of hunting crabs, Capn Jaq and her crew hunt “fractals” and the details of the hunt are just crab fishing in the Bering Sea with some names changed. But Jaq discovers that the ship run by her former lover is wrecked and goes to rescue him. I’m afraid I was turned off by the obvious origin of the story (there was no real attempt to file off the serial numbers or vary it in any meaningful way) and the fact that the resolution was telegraphed early on.

“Big Steel in the Sky” is a description of life building a space station. There’s little story here and the characters aren’t really important; we just get a description of the culture and the dangers. Clifford Royal Johns has put a lot of thought into the rules of that culture, but I’d much prefer a story about the people there rather than pure description.

We move from space to under the sea with “Air Supply” by Sophie Constable. It’s set in the deeps of the ocean, where Jenson is protecting a deep submersible from the live undersea. There is an attempt at sabotage, and Jenson suspects Rosa, an old friend of hers that shows up at the point of the breach. Rosa is uncovering a conspiracy, and tries to include Jenson in her plans. The story is a tad murky, and it’s a garden variety Evil Corporation revelation.

“The Heart of the Union” by Dany G. Zuwen starts out with a concept that is bound to cause confusion, but manages to avoid the pitfall of having two characters with the same name. Anne is the lover of another Anne, working in a space station that’s the pride and joy of a dictator. But the word comes through that it’s going to be shut down and the reaction is revolution. Most of the story consists of the revolutionaries making hard-ass statements and backing them up with violence until they get their way. Anne (the protagonist) watches it all happen and reacts. I loved the concept of a dictator building a space station for his own personal glory, but I don’t feel the story does much with it, especially since the revolutionaries come out of nowhere without any background except for a revelation at the end.

The anthology finishes with “Ember,” a story of a clash of cultures exacerbated when two people from two different ones fall in love. It’s set on a world filled with trees that have a symbiotic relationship with the humans (I assume) who have castes to take care of different parts of growing. Vals is a culler, who cut the weaker trees to avoid disastrous fires. Ita is a singer, who causes the trees to grow strong. The two fall in love, despite the disapproval of their social groups. Sabrina Vourvoulias had created a complex society and a sad story about how love may not be enough.

The concept for the anthology certainly deserves attention. But there is a certain sameness to the stories: the workers always are oppressed; bosses are always uncaring. That may say something about American society these days, but the lack of variation is a problem. A bigger problem is that, though none of the stories are actually bad, most are unmemorable. It certainly is decent reading, but I had hoped it would have been better.