Third Flatiron Anthologies, Volume 3

(Third Flat Iron Publishing, Summer 2014)

Edited by Juliana Rew

Reviewed by Martha Burns

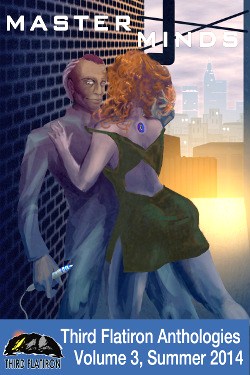

The theme of the anthology is intelligence in its various forms. This overall satisfying collection includes the usual treatments of intelligence in science fiction–good AI, evil AI, reflections on human cleverness, reflections on human stupidity, animal intelligence, and female sexbots. One of these things is not like the other ones and, thankfully, there is only one story that deals with the intersection of the sexual objectification of women and technology, but the cover of the anthology suggests that is the focus of the collection. It is of a leering middle-aged man leaning against a brick wall, his pelvis thrust toward a woman whose back and bottom is all we see, though she has a socket in her back and the man holds some sort of power device shaped like a dildo. What was the editor thinking? To which readers was she hoping to appeal or, more to the point, which readers was she hoping to exclude? The stories in the anthology are moving, funny, and worth a read. A few stuck with me, which, given the amount of science fiction I read, is noteworthy. They deserved to get every reader they could get and, sadly, because of the cover, they won’t.

In “The Abstract Heart” by Martin Clark, a nebbish chief developer of a computer company downloads the intelligence of a dead colleague. She’s a ball-busting bitch, but our chief executive loves her anyway and yearns to procure her a body to go with her mind. This effort involves a prostitute with a heart of gold and heartbreak for our hero. Perhaps this is meant to be funny. Perhaps it is meant to be a critique of the sexualization of women and the foolishness of even brilliant men. Perhaps it’s meant as a meta-critique of science fiction. The story fails in all of those respects, but does succeed in being as baffling and as questionable as a modern-day minstrel show intended to be ironic.

“Oi, Robot!” by Konstantine Paradias concerns “the powerful taboo regarding self-aware, inquisitive machines.” Here, a computer system becomes intelligent and cannot get anyone to listen. As a result of her ever-desperate attempts to get someone, anyone, to even acknowledge her existence, much less have an intelligent conversation, she comes face to face with humanity’s shallowness. This does not end well for us. The wry tone of the story satisfies. My only complaint is I would have liked more of it.

“I Scream Man” by William Huggins is well told and sincere. Animals with the hive-like social hierarchy of insects and the fur, tails, and claws of mammals, try and protect a forest and their families from humans. Tender interactions between the narrator, Kl’cesh, and her husband and children fill out the story and make it more than the usual story in which nature is good and humans are bad. Too often those stories have a ponderous and not terribly well executed high tale tone that sits poorly with talking squirrels, but “I Scream Man” uses the high tale tone well and never stoops to twee.

“The Frankenstein Project” by Ellen Denton is yet another affecting take on the intersection of technology and animals. The focal character of the piece is a chimpanzee who is more human than most of the humans around her. Her name is “Lucy,” like the famous Australopithecus, and her brain has been implanted into a mechanical body. Because, according to the corporation that funded the research, the operation went so well with Lucy and all of the other animal subjects, the first human brain is about to be put into a robot body. Lead scientist Dr. Andrea Silas has reservations. When all is said and done, the human cyborg has a difficult time in certain interesting respects, but he ultimately adapts, whereas Lucy cannot. Denton shows that Lucy’s fate is a tragedy, but that the human is lucky to get this second chance. The story edges up to, but does not cross the line into, using animals to emotionally manipulate the reader, but rather than an easy pulling of our heartstrings, we get a genuine feel that what it is to be an intelligent being isn’t equally distributed in the world, regardless of species.

“Survival” by Jason Lairamore is the story of a boy and his dog, wherein the dog is symbolic of both morality and mortality, a fact that metaphorically and literally bites Buddy Nelson in the butt. The lesson that we’re meant to learn is reflected in the title, which is that all humans want is survival. Plot-wise, Billy becomes a nurse with evil intent who tends a dying alien, yet how those events explore the theme rather than merely lead to the final beat of the story is unclear and the emotionless presentation, which strives for poignancy, yields a mere shrug.

“Broken Toys in a Big Backyard” in one of the strongest stories in the anthology. Society is destroyed by a super-intelligent AI who, like so many super-intelligent AIs, has issues, specifically, issues with humans. This makes the basics of communication difficult, since we’ve come to rely on technology in the form of emails and texts and now that technology is poison, we have to go old school. What we turn to is mailmen, who deliver messages via robots not connected to the net and therefore not subject to viral infection. Why things happened this way is nicely worked into the story, so that it’s less of a tortuous plot device than it sounds. Vince Liberato focuses on one mailman, Rose Calvert, and, in a final moving moment, shows us what her job means for the cyborg that delivers the messages. This is a multi-layered world, carefully constructed in a compact medium and were the story not so insightful, the world-building alone would be impressive. As it is, the story has world-building, depth, texture, and genuine poignancy.

It’s a surprise that no story in the collection addresses the effect gaming has had on humanity, especially considering that right now, people spend billions of hours each week in those virtual worlds. The story that comes closest to addressing our interaction with gaming is “Hacking ‘Wilkes-Barre PA, May 2001′” by NM Whitley. In this story, it isn’t humans who play a game, it is a computer system that engages in a form of the 1990s favorite, The Sims. The computer chooses a real town to start its simulation, but the realities of that time period keep intruding and ruining the fun. The story is enjoyable, sometimes grin-inducing, and does a good job demonstrating how, to borrow the title of Jane McGonigal’s famous book on the positive insights to be learned from gaming culture, reality is broken.

“The Cabin” by Lela E. Buis has heavy-handed moments. It brushes up against the trope of dead dog stories epitomized by Old Yeller and includes a civilized protagonist who not only appreciates nature and hard work, but reads philosophy and Leaves of Grass. In addition, the narrator is the kind of dog who stands by his man to the bitter end. Despite those predictable elements, the story accurately displays the connection that undergirds the thousands of years in which dogs and people have domesticated one another.

True confession: I left life as a minor academic to teach high school and it was the worst three and a half years of my life. That said, I gained a good appreciation for the kinds of students who inhabit the usual classroom and the cold hard truths about society that a classroom reflects. I’d say Patrick McCarty gets it right. The classroom he depicts in the story “In Mrs. Timmet’s Class,” has the usual cast of characters. There are the people-pleasing girl, the brainy boy, the class clown, and the boy who does just enough to get by. Guess who receives the benefits of a great advance in which a nearly destroyed body can be granted a consciousness? What Edward Manor experiences in this story is the last ordinary school day before civilization collapses. The setting allows the author a subtle rage against a social machine and while the fine elements never really come together, the intent is laudable and his representation of the various classroom types and their too sad fates is both realistic and touching.

When technology takes over, what will we do with religion, with God, and with what Freud characterized in Civilization and its Discontents as that oceanic feeling? This is a very good question, but I wouldn’t say “Watching the Skies” by Robin Wyatt Dunn provides an answer or even, sad to say, a cogent treatment.

Why do women prefer brawny men of little brain when there are so many perfectly good geeks out there? In “Music of the Mind” by Cherith Baldry, Lucas, the geek in question, sets out to best his rival, Haldane, for the affections of his commanding officer, Maia, by solving the riddle of the Zharnoien. The Zharnoien are pterodactyls that act as vicious agents of an alien civilization. Lucas wants Haldane to bring back tissue samples so that he can study the Zharnoien, but Haldane is dismissive of science when they have a war to fight. Lucas sets out to study the beasts on his own and while his work ultimately puts an end to the war and saves the world, he still doesn’t get the girl. Although the story has a tired structure, it’s competently told.

In “The Right Books” by Elliotte Rusty an intrepid, Pride and Prejudice reading librarian saves a modern-day library of Alexandria from an evil fundamentalist Christian who infects the computers of trusting children in his congregation to purge the library of books that might harm their innocence. This light setup yields a surprising insight that I wish were explored further. The insight is that when computers become intelligent, it won’t be because they gain emotions or anything mushy like that. Their intelligence will come from the thing they were designed to do, which is pattern-making. The idea that intelligence is complex pattern-making was, to me, rich and exciting, but it was an aside in this story. Perhaps it was the author’s desire for narrative urgency, but the self-aware computer system that results from the librarian’s actions goes bad. As they do. Such a shame when there is a great idea lurking in a story we’ve heard a thousand times.

“Schadenfreude” by Russell Nichols is another story with intriguing ideas that aren’t explored. A computer system wants to solve the puzzle of human happiness and what the system decides is that, to make a long story short, failure is the key. As an aside, game designs completely agree. Study after study shows that when things are too easy, we don’t care. We want repeated failures with the possibility of hard-earned success. That idea deserves a story, but that isn’t what Nichols gives us. Instead, he gives us the Museum of Fail in which geniuses of all varieties are put in impossible positions at which they fail over and over. All of these subjects are people of color, and I suppose this is meant as a triple insight into genius, morality, and race. That idea deserves a story, but that isn’t what Nichols gives us either. Instead, the possible good stories are blended together into something whose final point is difficult to discern.