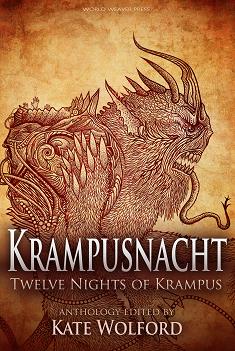

Krampusnacht: The Twelve Nights of Christmas

Krampusnacht: The Twelve Nights of Christmas

Edited by Kate Wolford

(Worldweaver Press, November 2014)

Reviewed by Martha Burns

Santa sees us when we’re sleeping and knows when we’re awake, he knows when we’ve been bad or good, so we should be good because otherwise we won’t get a Barbie dream house. Or we should be good because if we aren’t, a big hairy monster with hooves, stinking fur, a whip, and a sack for evildoers is going to get us and, though he began as a pre-Christian boogeyman, these days he’s on Santa’s payroll. Krampus is a figure of Germanic folklore who has recently come back into fashion as a forgotten pagan influence. This anthology asks and answers where Krampus came from, who would be his wife, and who makes his gear, while also questioning the true nature of evil.

Many of the stories are strong and the anthology as a whole is well worth a look, although I strongly suggest not reading the small introductions that come before each tale. These introductions give the inspiration behind the stories and sometimes spoil it for the reader, suggest the story is about something it isn’t about or, in the most unfortunate instances, prejudice the reader against the story. In particular, a number bemoan the greediness of contemporary Christmas and offer Krampus as a corrective. Yet Krampus, in its original and very pre-modern Christian context, is meant to contrast with the belief in St. Nicholas, the present-giver. Hence it isn’t modern-day capitalism that is to blame for Christmas being about the gifts. Second, the insight that Christmas is about consumerism these days, yet used to be pure in the days of yore, is a tiresome cliché. Third, implying that the reader does not know Christmas is about buying and selling suggests the reader is either complicit in the shenanigans or unaware. Most readers are probably well aware both of the many downsides of gift giving and that Christmas is what props up our economy, so good luck doing without it. So skip the intros and have fun. Krampus is a scary, woody, complicated, and mythical malicious presence we need more of, not because we need to be taught a lesson, but because things that could eat you always make good stories, especially in a time of year when the nights are long, dark, and cold.

Brian works at Super Fun Toy Store where he lusts after the boss’s daughter and tries to survive the store’s Christmas extravaganza, where each employee must wear a costume and play a part for the customers. Things look bad for Brian when his comically long tongue lands him the role of Krampus (complete with stinky fur suit), but Brian, generally mild-mannered and unassuming, finds his inner Krampus once he puts on the suit. And then . . . stuff happens. The first third of “Prodigious” by Elizabeth Twist is funny and light, then the tone seamlessly shifts darker and we both cheer for the new Brian and wonder how far he will go. The plot falls apart when a conspiracy against Santa and a pit with “chthonic mysteries” show up. Read the first two-thirds, where the shape of the story sticks to Brian’s transformation, and you will be satisfied.

“The Wicked Child” by Elise Forier Edie is the story of an abused gypsy child, Tuva, who turns out to be better than her shallow fellows. Each year, a bishop and his companion visit the village, and one year the companion is kind to Tuva and empowers her with a gift, which allows the townspeople to see their innermost desires. We see that the bishop is a stand-in for St. Nicholas and the darker companion Peter is Black Peter or Krampus, hence, through his friendship, the story suggests that wickedness can be a revelation. Conformity is more comforting to the townspeople than the pain of longing. The treatment is more nuanced than one would expect from a story that has a heavy-handed moral. Tuva is sweet but not treacly and the townspeople are cruel, but not inhuman. That is, unless one reads the editor’s introduction, which is the first of the anthology to announce the author’s view that Christmas has lost its purity and has become an excuse for us to revel in our own decadent and shallow consumerism. This trite trope reminds us that Christmas has been the season of moral censure since Dickens, which saps joy faster than any black Friday could ever manage.

Felix is a rotten big brother who, the moment he shows up on the page, we hope gets stuffed in Krampus’s sack. “Marching Krampus” by Jill Corddry is a short, delightful tale that you do not need to be a younger sibling to smile at.

“Peppermint Sticks” by Colleen H. Robbins is layered and unexpected. Steven is unemployed and desperate. Mr. K saves Steven during the Christmas season and sets him a series of unusual tasks we, along with Steven, wonder about. We share Steven’s sense that he’s being manipulated, but neither of us can see where this is going. In February, he makes an unusual discovery about fantastical creatures; in May he watches the delicate creatures romp; at the Summer Solstice, Steven finds an unsettling and brutal component of their lives, and at Halloween, Steven gets asked to be the agent of pain for humans, all in preparation for the final smackdown of bad children at Christmas. The story turns on peppermint sticks and transformation, answers where Krampus came from, avoids the cliché that Krampus is secretly the good guy, and restores our faith in humanity. Recommended.

Stargazer has come up in the world. She began life as the only daughter of a brutal man and is now an anthropologist/sociologist sent to study the tiny village of Eull, where the winter nights are cold and dark and there is no crime. She meets the man of her dreams, which violates the divide between researcher and subject, but she cannot help herself, even after the villagers warn her to leave. Throughout the story we get bits of songs about Krampus that are eerie in the extreme, such as “Ring, Little Bell, Ring,” also the title of the story. Caren Gussoff brings it all together in an adult and dark Krampus tale only dampened by, once again, the editor’s introduction, which promises this is a story about Krampus dating. The result is that we’re prepared to read something light, maybe even the Bridget Jones of Krampus, and it takes time to adjust to the reality of a grownup story. Recommended.

“A Visit” is set in Victorian times where Krampus saves his family, society, and the reader from the nastiness of a man so cruel he’ll make a child miserable for wetting the bed. Like any Victorian patriarch in fiction, the bad man in this story has a thing for housemaids, is an inattentive husband and is, Scrooge-like, an unscrupulous businessman. Mr. Pennyrake needs to go and Lissa Sloan gives him a fitting end. He is so very bad we’re satisfied and also enjoy the spin on the Victorian Christmas, but at this point in the anthology, the number of avenging Krumpuses has become a little tiring, though this is an artifact of collecting Krampus stories together and our contemporary expectation that the villain is really the hero, neither of which ought to be held against the author.

“Santa Claus and the Little Girl Who Loved to Sing and Dance” by Patrick Evans has an excellent premise. Poor Santa is tired of all of that good cheer and wrestles with the part of him who wants to give people what they really deserve and that part of him seems to be struggling to get out, both as a repressed portion of his psyche and in a creepier way reminiscent of Aliens (if Krampus were the creature). Great premise. Too bad every female character is a grotesque. This is played for laughs, but the story fails because satire doesn’t work when the critique is aimed solely at one gender and when the focal subject is one that, in real life, is likely to be unfairly reviled. The chief villain of the piece is a fat little girl. Fat little girls are more often than not treated cruelly in real life, ergo, hard to make fun of. Then Mrs. Claus shows up and doesn’t appreciate Santa even though he rebuilds their home and then she leaves him until he gets his act together. Overly demanding and unappreciative spouses can be funny, yet this starts to feel questionable when coupled with the nasty fat girl. A celebrity shrink is always good for laughs, one might think, but when this becomes the third female character pitted against an all-suffering male character it is, at this point, really not so funny and, no, things do not get better if the wicked child prevails. This is a head-scratcher.

Krampus walks into a bar and gives you a choice between dying from a bullet between your eyes or being set on fire. You just want the crazy guy who is spoiling your depressing Christmas at the bar to shut up, so you tell him something and then he goes away. Strange things, some of them good, some of them bad, begin to happen. Your life suddenly gets fantastic when you’d been spending that depressing Christmas in the bar because you’d just been sacked. You now have the lovely wife, the lovely house, and a growing sense of dread as people around you start to die from either a bullet between the eyes or immolation. “Between the Eyes” by Guy Burtenshaw keeps the tension going. The coda is a choice I don’t quite understand since it doesn’t fit the pattern that’s been established in the story, but the story is otherwise engrossing and provided a welcome bit of holiday horror. Recommended.

“Nothing to Dread” by Jeff Provine is a story in which a little boy shows Krampus the Bible and, like a vampire confronted with a crucifix, Krampus hisses and cowers. Jakob, our young Van Helsing, proceeds to use the power of Christian charity to defeat an unfeeling foe whose understanding of evil is too simplistic. The premise, that Krampus is not one to judge and the nature of evil is strong. I would very much like to see that story, but this one falters by being too on the nose and, as a result, comes off as both unintentionally silly and preachy.

In “Raw Recruits” by Mark Mills, Krampus has a legion of evildoers to make his switches. Each year a bunch of new “recruits”–very bad people–show up, but Krampus must eat, so with every arrival of newbies, the question becomes who of the previous year’s crew will live another year and who will die. If your switch is evil through and through, you make the cut. Our narrator is gifted at evil and proves it better than any Grinch. The story has a fun and unusual focus, which isn’t what the introduction to the story suggests, so, once again, please do not read the introduction, which says Krampus is needed when there are so many greedy little children out there. You will enjoy this twisted and inventive addition much more if you don’t go into it thinking it’s the same old thing. Recommended.

The narrator of “The God Killer” can see demi-gods, one of which is Krampus. One night, the narrator spots Krampus and follows him as he kidnaps bad children. The narrator takes decisive action and then asks the gods who sit in judgment to wait and judge only after they’ve heard the full story. Cheresse Burke keeps tension going nicely, but also shies away from gore and close descriptions of the terrified children. While this gives the story the feeling of a realistic first-person defense, where the speaker sticks to the facts, without those details, I felt something was missing and that I wished to know more so that I could truly feel the vengeance.

When John Nast wakes up one morning to find his plastic reindeer and Santa have been posed in undignified ways, John vows revenge on the teenager next door, who John is sure is the culprit of this and other Christmas misdeeds. John’s grandfather was German and told him about the punisher of evil children, Krampus. Heck, many years ago when he was a police officer, John even dealt with teenaged hoodlums with a little act he and his fellow police officers called “the Krampus treatment,” which involved terror, though no actual violence. This is a misstep. Because “the Krampus treatment” was meant to frighten teenagers who were driving drunk, it’s possible to excuse it, yet John pays for his policeman’s sins in Scott Farrell‘s “Krampus Carol,” while the lawn defacer is portrayed as deserving sympathy, all with an ending that involves too much explanation.