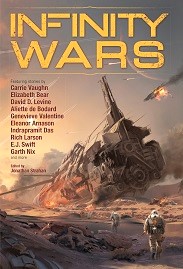

edited by

Jonathan Strahan

(Solaris, September 2017, pb, 364 pp.)

Reviewed by Jason McGregor

Infinity Wars is the sixth in Strahan’s Infinity series of science fiction anthologies (which may be more branding than a coherent series at this point) and this one unsurprisingly focuses on future war. While the quality of the content is ultimately good, it is a surprisingly poorly structured (and sometimes proofread and edited) book. There is no standout story in the entire first half and, while an argument could be made to start with the “calm before the storm,” it actually results in a dull and unengaging start. Another aspect of the start is that there are three consecutive stories set on space stations (none with regular combat protagonists) and only one or two more for the rest of the book, while climate change is barely addressed until the last three all focus on or spring from it. Two consecutive early stories go so far as to be almost identical in terms of their handicapped protagonists’ dilemma and decision.

While no story is entirely off-theme, and giving a variety of non-combatant and atypical combatant perspectives is essential, very few deal directly with soldiers in physical combat and very few are viscerally traumatic, giving a real feel of war. Again, almost all those are in the second half. Conversely, only one story even begins to touch on any possible attraction of war. Wherever the reader is on the militarist-pacifist scale, the failure to confront this historical and psychological reality will likely be seen as a shortcoming. Some recurring motifs are soldiers who don’t like telling war stories, more or less clever contortions from authors to explain how weapons advances don’t result in at least global annihilation, much grappling with issues of personal responsibility, and many depictions of future wars being driven, not by expansive aggression or ideological dreams, but by desperate scrabbling for dwindling resources.

While the structure breaks into halves, the quality breaks into thirds. The most effective for me were the de Bodard, Levine, and Swift, with the Larson and Watts also deserving special note. Of the remainder, about half made par. While the anthology could have been improved, in my opinion, with some changes of focus, a rearrangement of the stories, and some grappling with war’s persistent allure, the number, power, drama, and idea content of the winners and the overall quality of the rest make this a good buy. (Be warned, though, that this is an extremely padded book, having only about 300 words to the page, totaling only around 100,000 words, with no novellas.)

“The Evening of Their Span of Days” by Carrie Vaughn

All’s quiet on the galactic front until we see how the outbreak of war affects the non-combatants of a space station shipyard.

This gets off to a poor start, with a “kingdom” whose ruler has a “supervisor” (the ruler more properly has a fief), and a cap which “looked frustrated” (rather than serving as a sign of its wearer’s frustration). And that’s just the first page. After the story is read and viewed whole from a distance it’s not bad, but it clearly needed another draft. Regardless, there’s no special reason for this to be science fiction. It nicely describes a space station and a space ship but might as well have nicely described a shipyard and a sea vessel. The character and her essential experience would be the same.

“The Last Broadcasts” by An Owomoyela

One of Sol’s colonies is under slow attack from aliens. In order to avoid interstellar panic, this is kept secret by a misinformation group (which is barely possible given the story’s social structure and imaginary physics of controlled FTL comms and STL physical travel). When a neuroatypical vegetarian colonial shows up on a space station for her mysterious new job and learns she’s to be part of this group, her moral objections lead to a crisis.

The protagonist’s belabored attributes have little or nothing to do with the scenario or necessarily with her reaction to it. More importantly, the story is grotesquely under-motivated. (A new person with little knowledge simply decides she Knows Best. A junior supervisor instantly befriends her at great potential cost. The Sol supervisor is classed as a jerk without having been much of a jerk.) Many “outsider comes into a situation and rebels” stories have been written and they can be great but this story wants to convey its theme and doesn’t do the work to make it persuasive in even a fictional sense.

“Faceless Soldiers, Patchwork Ship” by Caroline M. Yoachim

When the Faceless arrive to finally defeat humanity by adding the fire kittens’ teleporting ability to their own with the Patchwork virus, Ekundayo’s sickle-cell trait makes her somewhat resistant to the virus and the best person for the job of delivering a counter-virus. With her half-sister and half-human/half-alien friend in support, she leaves their space station for the enemy vessel. When she discovers it’s a hospital ship and that the aliens aren’t what she thought, she has a decision to make.

This is television-grade sci-fi and seems almost like a profanity-laced YA tale. It’s hard to take seriously as modern adult print science fiction, but it may entertain some. I do like its use of the sickle cell “defect” as a positive because, on the doorstep of gene editing, it underscores that we don’t know what traits are “desirable” and “undesirable” and that these values change with circumstances.

“Dear Sarah” by Nancy Kress

After aliens arrive and put many humans, including MaryJo and her family, out of work with their technological gifts, she feels her only option is to join the army. Since the army is suppressing anti-alien groups, her family isn’t pleased (though sister Sarah misses her). A fellow recruit befriends her and shows anti-alien sentiments, herself. When that recruit tries to take action, MaryJo has a decision to make.

This is another not-always-convincing mountain folk story from Kress and sometimes too much like “Pathways.” (This: “If its name was ‘Mr. Granson,’ then mine was Dolly Parton.” “Pathways”: “if she was ‘Jenny,’ I was a fish.”) The symbolism is transparently veiled but the story is competently executed.

“The Moon is Not a Battlefield” by Indrapramit Das

An Indian soldier who was taken from the streets to fight a semi-cold war on the moon is being interviewed years after a reporter first met her.

This story is quite poetic in places and is the first story that addresses the seductiveness of war as well as its repelling aspects and which features an actual soldier instead of a civilian or raw recruit. It paints a complex and intriguing picture of space elevators, moon bases, international tensions, personal struggles and, ultimately, the discovery of FTL which transforms those bases. However, the fact that it is an interview and is not plot-driven leads to some distance and dullness. Then the conversation gives in to unoriginal preachiness.

“Perfect Gun” by Elizabeth Bear

A mercenary, with at most a vestigial conscience, buys an AI war machine and breezes his way through his tawdry life until he runs into someone even less honorable.

The ironic antagonist-as-protagonist approach was almost clever and did give the story more zip than some but was laid on incredibly thickly. AI war machine or not, it wasn’t especially science fictional in essence. After the directness of the bulk of the tale, the conclusion was unsatisfying. At least it was an energetic read but something like her earlier story, “Tideline,” would have been a better contribution.

“Oracle” by Dominica Phetteplace

Rita became an internet success when she founded the “nail-polish-of-the-month club” which uses data-mining to give customers freedom from choice. Despite more, similar successes she feels dissatisfied and decides that what she needs to crown her resume is world peace, so creates an AI to bring that about.

Some may find this tale lively and amusing, but it ultimately trivializes war and peace in a way that some may find offensive. It also blames war not just on Americans, but specifically on male Americans. (“The men at Defense certainly couldn’t be trusted.” Are the many women at Defense supposed to be trustworthy or are they not supposed to exist?) Finally, the rewards given to the superficial twit of a privacy-invading robot-overlord-installing protagonist seem to endorse her in facetious but un-ironic terms.

“In Everlasting Wisdom” by Aliette de Bodard

An Everlasting Emperor maintains rule through a bureaucracy which includes “harmonisers” (people implanted with alien symbionts which help convey a psychic wave of calming propaganda). Our protagonist is one such, driven to the job by the need to care for a starving daughter. She meets a woman who was much like she once was, who attempts to assassinate her. Rather than turning her in, she gives the woman some food and sends her on her way. Meanwhile, the growing discontent of the people with their Emperor comes to a head.

It’s ironic because I’m not a fan of this author’s (generally well-regarded) work but this is the first story of the anthology that was excellent. While I think the Empire is evil and anyone serving it is complicit, the story shows how hard it can be to resist and how complex such a servant can be. The aliens are simultaneously horrifying and sympathetic. The desperate assassin is as complex as the main character and their second meeting is actually moving as she, the host, and the symbiont try to understand each other. While relevant to current earthly situations, it is highly reliant on its speculative features and is well-constructed. The only objections are that it has perhaps a bit too much sympathy for the devil and a certain leaden quality to the prose and story movement, along with making the inexplicable choice to do unnecessary violence to the English language by referring to the alien as “they” rather than “it” or another singular pronoun. But these quibbles are all very minor in relation to the whole.

“Command and Control” by David D. Levine

This very MilSF tale tells of the possibilities and limitations of weaponized teleportation through the mechanism of an Indian-sponsored effort to liberate Tibet from China. When a squad leader of the decentralized Indian effort discovers the location of the leader of China’s centralized forces, she has a remarkable opportunity if only she can work around her superiors and execute a desperate mission.

Arguably, the complicated checks and balances on the weaponry and other tech don’t add up to a plausible future or specifically plausible battles, but it is arguable rather than ridiculous on its face, however much a knee-jerk reaction might make it seem. Generally, this story is taut, fast-paced, cleanly written, with perhaps less depth than “In Everlasting Wisdom” but with much more zip and technological speculation.

“Conversations with an Armory” by Garth Nix

Abandoned by their government, but facing an alien attack no one else is capable of repelling, a ragtag band of handicapped veterans on a converted hospital ship argue with a half-decommissioned sentient armory to try to break out some weaponry to help them meet the assault.

Unconventionally done in pure dialog with no quotations or speaker attributions, this puts up unnecessary roadblocks to understanding and appreciation but turns out to be adequate.

“Heavies” by Rich Larson

Dexter’s a “heavy” (Earther) monitoring a colony world which rebelled fifty years ago but which has been pacified so its moons can be mined by the Earthers. He learns about the world from his native lover, Roode, and we learn from them. However, when the peaceful natives are suddenly gripped by mass psychosis and begin killing heavies, the situation becomes dark and dire and Dexter learns just how heavy the Earther hand is.

I have a logical problem with this in that it is stressed that the colonists have been modified to suit their low-gravity world and are very tall, thin, and weak, so it’s odd to me that they can kill so many heavies so easily, especially as it’s often in hand-to-hand combat such as strangulation attacks. Still, it’s extremely gritty and effective and, while describing just a relatively small insurgency, feels somewhat like war and to a greater extent than most of these stories.

“Overburden” by Genevieve Valentine

A Colonel bucking for General during a conflict with another group turns out, with brutal irony, not to be General material at all.

This story is overburdened with faulty exposition as the first few pages dump Cirrus, Cirrus Prime, the Glorious Forces, and many named characters on the reader and almost none of it is clear or amounts to much. While partly intentional, the protagonist is unengaging. The story itself is clever enough but makes no impact.

“Weather Girl” by E. J. Swift

Lia is a black ops “weather girl” who weaponizes “typhoons.” Her group hacks other folks’ weather satellites and systems to conceal megastorms until it’s too late to evacuate and then reveals the storms for maximum hysteria. Nicolas is her ex-husband and current vagabond who drifts to the wrong place at the wrong time.

This is a climate change story with an interesting specific concept and a relationship story which makes the relationship element pay off. Like the Vaughn, it could have benefited from more vigorous proofreading and editing and, like the Owomoyela and Levine, it strains but doesn’t entirely break credulity. I wasn’t initially too involved but, like the rising winds and tides, the story picks up and its smashing idea puts it over the top. Harrowing and effective.

“Mines” by Eleanor Arnason

After we ruin Earth, we invent FTL, discover a habitable world, and some of us go off to ruin that one, too. Or perhaps not. With sporadic fighting between two competing colonies and conflict back on Earth, this is actually the tale of a PTSD ex-soldier and her mine-sniffing augmented rat and the crazy girlfriend she meets.

There’s nothing especially wrong with this story and the rat (unaugmented versions of which are real) was interesting.

“ZeroS” by Peter Watts

Kodjo Asante is killed by folks scrabbling over the dregs of an environmentally ravaged Earth but is fortunate enough to have some military folks come along, jumpstart him, and ask him if he wants to live in exchange for becoming a zombie warrior. He agrees, and we follow his training and first few missions in which his subconscious mind is given the keys to his body and he becomes a superwarrior. But, no matter how tough a son of a gun you are, there’s always someone tougher.

This is a difficult story to summarize and evaluate. It’s partly “yet another zombie story” though only two of the unit were actually dead and isn’t the most plausible story, either way. And I ended up disliking the protagonist due to his misplaced moral quandaries. But it does have ideas, is dramatic, and granting the premise and the protagonist, is well done.

More of Jason McGregor’s reviews can be found at Featured Futures.

Infinity Wars

Infinity Wars