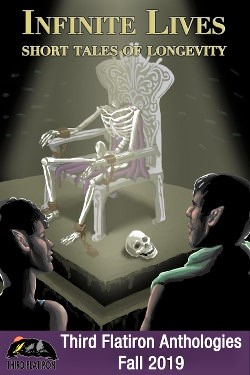

Infinite Lives: Short Tales of Longevity

Infinite Lives: Short Tales of Longevity

Edited

by

Juliana Rew

(Third Flatiron Publishing, Fall/Winter 2019, pb, 276 pp.)

Reviewed by Geoff Houghton

The stories in this original anthology range from SF to fantasy, but all ponder the broad issue of mortality.

The opening story is “Tunnels” by Brian Trent. This is a stylishly written story with an upbeat ending. The narrator, Niccolo, is an immortal, born in fifteenth century Venice. Niccolo has loved and lost across the centuries until he finally becomes a desert-dwelling recluse on a newly colonised Mars. When he rescues an injured colonist and once more falls in love he fears that the cycle of loving and losing is about to begin once again but discovers that science has finally caught up with nature.

The second offering is “A Billion Bodies More” by Sloane Leong. It is set in a technologically advanced prison with only one inmate. She is Iala Red-of-Palm, a space general who won her war by means so abhorrent that her own people cannot condone her methods. Her punishment qualifies as cruel and unusual but Iala proudly accepts her fate and shows no contrition for doing what had to be done. The reader will have to decide for themselves if she was right.

The third offering is “Del Boy Falling Through the Bar, Forever” by Matt Thompson. This tale is set in a near-future world where an all-powerful world-spanning AI is determined to make every citizen happy—whether they want to be or not. Re-education camps exist to “help” those who are not enjoying themselves enough and even suicide is most often punished by rebirth. The hapless protagonist in this “utopia” is finally offered an exit route if he will join and betray the limited resistance to the AIs’ autocratic rule. However, even that is not entirely what it seems. The reader is warned that at least a passing knowledge of UK situation comedies from the third quarter of the 20th century is necessary to understand many of the cultural references in this story. So if the title means nothing to you then you may find much else in the story to be equally obscure.

Fourth in the anthology is “Left of Eden” by J. B. Toner. This is a tale of fantasy vs technology set on a near-future Earth. The story premise is that if human scientists should ever detect paranormal activity then human industry would find some way to harvest and exploit it. Michael Delving is the CEO of just such a company, but his ruthless efforts to rise to the top of this business have only one ultra-ambitious aim. In the Middle Eastern desert is the last remnant of Eden, The Tree of Life is still guarded by the mighty angel who cast Adam and Eve out from the garden. But Humanity has advanced whilst Heaven has stagnated. Is a flaming sword still enough, or is it time for humanity to take back what had once been its birth-right?

Next is “A Last Word” by Larry C. Kay. This is a pure SF story set on a ruined Earth several centuries into the future. The narrator is an old woman, the matriarch of a multi-generational dynasty family, although the reader will gradually discover the true nature of those children. More detail would ruin the surprise ending, but this is a short, delightfully written tale that explores one possible way that a post-apocalypse Earth need not be a dystopia.

“Dry Bones” by David F. Shultz is a quest set in a classical fantasy world. A knight and his female squire (nice to see equal opportunities even in the high fantasy world) seek the cavern where a great elven sorcerer had been imprisoned for seeking knowledge that elf-kind should not know. The sorcerer had manufactured an elixir of immortality before his peers had sealed him forever in the cave and left him there to die. Neither they nor our questing knight had thought through all the permutations of angry sorcerer, inescapable trap and a vial of immortality serum. The reader may already have deduced that the addition to that mix of a questing knight with a magical key was never likely to have an entirely happy ending.

“Only the Poor Die Young” by D.A. Campisi is an amusing tale that converts the Judeo-Christian tradition into untrammelled capitalism. This is another fantasy story, but set firmly in a recognisable USA in the near future. Edgar Strand is a thoroughly ruthless businessman who has already lived for 197 years. Death has been privatised and only the poor die young; the rich can buy deferments. The catch-22 of purchasing a way out of death is that the premiums needed to hold off a timely demise increase with each year of life. All of our protagonist’s fortune has now been spent and Death’s smiling upbeat minions cheerfully ease him into the next life. There, Edgar discovers that Heaven has also been privatised but that the tender required to pay for the super-deluxe Heaven Experience is a different sort of currency entirely.

Next is “Long Stretches” by Russell Dorn. It’s a disturbing but worthwhile SF read. The scene opens in a wrecked spacecraft in which one of the crew has been trapped in a single compartment for more than two months. That would be bad news in and of itself, but the reader will slowly develop the feeling that all is not as it seems. Are his children completely normal children? Is the ship’s Captain an entirely typical spacer? To say more would ruin the point of the story.

“Professional Envy” by Samson Stormcrow Hayes is set in the modern Western world with one fantasy element. The narrator is a struggling author, but a successful vampire. The professional envy of the title is his jealousy of a highly successful writer of supernatural stories. Our protagonist has struggled to find an audience for his own vampire stories. To his great annoyance they are considered to be unrealistic even when he writes non-fiction accounts of his own experiences. The interaction between human and vampire does not go exactly as you may expect but the average reader may find it difficult to sympathise with the dilemmas that go with being a murderous vampire.

Tenth in this anthology is “At the Precipice of Eternity” by Ingrid Garcia. This is a thoughtful SF story set on a near-future Earth. Professor Carman Salomon wakes with dream visions in her head and those visions have led her to her most fruitful breakthroughs. Now she is poised to complete the greatest biotechnological discovery in the history of her species, a method of offering immortality to humanity. On the eve of publication of her work, she learns that she has been the tool of an ancient and powerful alien species. They have broken the non-interference rules of the Galactic Council to give her that gift. Now a second, equally ancient race also intervenes to inform her that immortality at this stage will only stunt the development of humanity. Humanity must be mortal in order to evolve or they will never reach their destiny. She is warned that immortality is a trap used by some unscrupulous alien races to prevent the development of potential rivals. The author leaves the reader to decide who is lying, who is friend, and who is foe.

We return to fantasy in “Frost on the Fields” by Maureen Bowden. This is a story of love, loss and magic set upon the mystic Isle of Ynys Mon (now more prosaically known as Anglesey, Wales). Key players include a half-goblin biker and his motorcycle club, a 2000-year old Celtic warrior, now dying in an Anglesey nursing home, Creiddylad, the goddess of flowers, and her jealous spouse. This is not quite a spoof but it is certainly an idiosyncratic take on the classical norms of Celtic legend. Therefore a certain knowledge of their rules would enrich reader understanding, but it can still be read as a free-standing piece.

“Secrets from the Land Without Fear” by Brandon Butler is a darker fantasy than “Frost on the Fields,” although with an uplifting ending. The Land of Fear is a technological world akin to 20th century Earth. A few inhabitants of the Fairy Realm visit that Land for carnal reasons, others cross over for the sport of it and some out of sheer curiosity. Lyseil is a fairy sprite fascinated by the fact that the fairy realm is unchanging but that the world of men is vibrant, mutable and so impermanent. Her meeting with a half-fairy, half-human warrior teaches Lyseil that play has consequences and that the human inhabitants of the Land of Fear are then the ones forced to pay that price. Her effort to mitigate that cost for at least one of the Land’s inhabitants may be limited in scope but has good intentions.

“When They Damned the Name of Oma Rekkai from Memory, I Danced” by Caias Ward is set in an advanced prison with only one inmate. This is a more nuanced story than the similarly themed “A Billion Bodies More” (the second story in this anthology) and may be the star of the entire collection. Once again an only-too-competent space general is imprisoned after winning her war, although Oma Rekkai’s prison is far more luxurious than the tortures of “A Billion Bodies More.” The story is told from the point of view of Lorna, the most recent of a series of companion/guards who serve six months on the prison world and then are mind-wiped of that entire experience so that the name and deeds of Oma Rekkai will never again be known to the innocent people of the universe that she saved. It becomes obvious to Lorna that Oma Rekkai had allowed her own capture and could have escaped her prison at any time. Even in her extreme old age Oma Rekkai understood that those who forget their history may be forced to replay it. The aged general knows that ending her own life will close that prison down and send her jailer home. But Oma Rekkai has programmed Lorna in the most subtle and undetectable manner to be one step ahead of those who would ignore and conceal history.

The fourteenth offering is “Thoughts of a Divergent Ephemeron” by Leah Miller. This SF story initially appears to play out on a futuristic Earth perhaps a century or so forward from today. But the narrator gradually discovers that his entire world is a simulation, a playback of his life, and that in the real world he is already dead. Even worse, the simulation is starting to seriously diverge from the baseline reality so that those who are running the simulation are beginning to question the point of continuing to run it at all. Our protagonist handles his discovery of that frightening truth with great dignity in this quiet and subtle tale of alternative realities.

We return to fantasy for “The Scarecrow’s Question” by Megan Branning. This is set in a quiet, civilised agrarian successor to our materialistic world and the writing is equally mild and gentle. The scarecrow’s question has been posed by philosophers throughout history—when does something cease to be itself if you gradually change its components? He does receive an answer but it is the journey rather than the wisdom of the answer that ends up having the greater impact.

“Abe in Yosemite” by Robert Walton is an alternative history story. The alternative considered is that Abraham Lincoln survived the shooting at Ford’s Theatre at the end of the Civil War and lived into his seventies. The author rather lovingly describes the retired President’s reactions to the beauty of the Yosemite National Park, which Lincoln authorised but never saw with his own eyes. However, there is not even a tantalising hint of how that single but seminal event might have changed events outside of the park. Perhaps the author may have intended the reader to draw their own conclusions but that absence converted a fascinating prospect into a tale of an old man’s final, gentle retirement from life.

We return to hard and gritty SF with “Wishbone” by K.G. Anderson. This story is set in the United States a decade into an almost recognisable future. The response of the land of capitalism and consumerism to reaching the maximum limits of consumption is “The Age Equity Act.” State and Federal Benefits to the elderly would be progressively cut from age 72 up to 79 and at 80 the elderly would be required to report to End of Life Centres in order to free up goods and services for others. The narrator is the 79-year old grandmother of the politician who introduced these measures and the rest of his family are vociferously divided on what must be done for or to Granny. The plot winds most satisfactorily to a conclusion that proves that not only politicians can be deceitful and devious.

“The Reinvention of Death” by Louis Evans is set on an ancient Earth. It is SF rather than fantasy, but the science is that of galaxy-spanning super-humans. They convert their birth world into a tribute planet on which death is abolished for every living creature before they depart for realms yet unknown. The story is told from the point of view of the last of the guardian robots left behind to tend their final memorial. After multiple millennia of stasis, death finally returns to the garden. But with death comes birth. The long-delayed cycle of nature finally restarts. Creatures recommence their interrupted evolution and the final thoughts of the last fading guardian machine are not for what has gone before but what is still to come.

The eighteenth story is “President Redux” by John Paul Davies. The location is a near-future Earth. A bloody civil war rages across what remains of a nation. One side has the better general and more fighters. The other has possession of the rightful President and little else in its favour. The second faction maximises that slight advantage with technology and surgery. Much can be done and risks can be taken as long as you have an adequate supply of expendable Presidents. The story of a single day in the ongoing struggle is told from the perspective of the most recently manufactured ersatz president.

The world described in “Sweet Release” by David Cleden considers a possible SF future that may come to pass within the lifetime of some child already born. Sentios Corporation has lost its CEO and founder in a sudden and unexpected road accident, and like many such companies, their founder is also their greatest asset. Facing disaster, Sentios turns to their two latest experimental products. They plan to create a neural construct that will emulate their lost CEO based on the data from a life-logger that he has worn for a decade or more. Yet not even that amount of data is enough to create an adequate copy. They need more. They must have the memories of his closest co-workers and especially the most private and closely held memories of his estranged wife. The latter finally agrees to cooperate but extracts a bizarre price.

“Chosen” by Tom Pappalardo is a cheerful, wisecracking fantasy in which the Incarnation of Death visits a small New York café to recruit his successor. Readers of Piers Anthony’s On a Pale Horse or many of Terry Pratchett’s discworld series may recognise many of the characteristics of this Avatar of Death, but not even the Incarnation of Death is quite prepared for a pair of modern, feisty New York ladies who run this cafe.

“Like a Seagull, Hurling Itself into the Mist” by Philip John Schweitzer is one of those stories that are almost impossible to categorise. It is (probably) SF. It occurs (possibly) in the far future on a world somewhere far from Earth. It is the story of the last few days at the end of the lives of two ancient sentient constructs. Why they were constructed, who commanded it to happen, whether they achieved their goals or were just abandoned are not only opaque to the reader but are (probably) unnecessary questions. It may be enough just to absorb the message that you do not have to be human to live, love and be loved.

We return to fantasy in “Found Wanting” by Martin M Clark. This story of supernatural power is set in the wilds of the western USA in the present day. The narrator has the uncanny power to transfer years of age from one human to another. When he stops a robbery with that power, the cascade of events triggered by his action end with him acquiring a new life partner. The amount of murder, mayhem and gunplay in this piece may lead you to believe that the author must be some sort of redneck Texan with a disdain for any government interference in his second amendment rights, but he is actually a Scottish government official and part-time poet.

“Cold Iron” by Wolf Moon is a supernatural fantasy set during the Spanish conquest of the New World. The narrator is Don Capricho Delgado y Cervantes. Although he was born Castilian he takes up arms against the Conquistador Francisco Pizzaro when he discovers that Pizzaro and some of his men are no longer human but have become servants of a darker power. Even with the aid of a powerful witch and the local Earth Goddess, he cannot save the New World from the conquerors, but perhaps he can at least save the conquerors from themselves.

“The Last Son of Geppetto” by Mack Moyer is another supernatural story set across a period of fifteen decades from the American Civil War to modern times. The sorcerer Geppetto called forth a dead soul and bound it into the wooden body of a marionette. However, the spell was flawed and the puppet escaped the sorcerer’s control. Since then, the marionette has sought redress and revenge, first from the sorcerer who did the wrong, but then from his descendants. Now the marionette confronts the last son of Geppetto with a horrifying revenge.

The final offering in this anthology is “Find Her” by Konstantine Paradias. The narrator of this sweeping fantasy is the demon Akoman. His nemesis is the angel Muragit. This equally matched pair wage war across the ages and across all the battlefields of Earth and Heaven on behalf of their masters, the high deities of the Zoroastrian religion. Over the thousands of years of combat they gradually develop an affection that eventually becomes love. They attempt to escape the wheel of fate to be together but the gods themselves conspire against their love. Yet in the end, even gods and religions eventually fade and love is forever.

Geoff Houghton lives in a leafy village in rural England. He is a retired Healthcare Professional with a love of SF and a jackdaw-like appetite for gibbets of medical, scientific and historical knowledge.