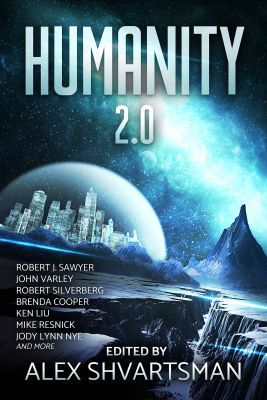

edited by Alex Shvartsman

(Phoenix Pick, October 2016, 272 pages)

Reviewed by Jason McGregor

Edited by Alex Shvartsman, an editor who I believe is best known for humorous anthologies, Humanity 2.0 brings us nine original and six reprinted serious stories which aim to portray some ways in which humanity might need to change in order to go to the stars or be changed by having done so. The first half of the original stories are not especially strong overall but the second half improves markedly.

“Justice and Shadow” by Angus McIntyre

In a small cluster of suns, solar sail ships make the rounds from world to world. The ships’ societies have degenerated into specialized castes (more nearly species): those who work on the sails (in units of three), those who work on the lines, those who live in the habitats, etc. This specialization includes biological alterations, such that sail folk can survive conditions in space that hab humans cannot. Justice is one of these sailors and has left a triple she once shared with Shadow (and someone else we don’t seem to care about) and, more than that, she and her new triple have left the sail altogether. Shadow is recruited by the sail “queen” (or volunteers) to go after Justice in an effort to bring her back. She then discovers Justice is carrying a hab human in a spacesuit from the sail to ship-parts unknown. Discovering the significance of this forms the bulk of the tale.

This is a frustrating story as the author has apparently thought a great deal about the setting and some about the social structures and apparently has something to say thematically but has produced a highly schematic story that has no character and no plot beyond a conventional, but incomplete, “quest” structure. Even on the social structures, one might expect the “triples” to be explained by reference to, e.g., sail work having been a “three-man (person)” job and/or expect the “triple” to have numerological significance but there is little or none of this. One certainly wonders why all three of Shadow’s triple must go out with her but, when Shadow defies her Queen and continues the pursuit after the Queen has a change of heart, the other two may return by themselves. And wonders why the Queen changed her mind and what exactly the costs of defiance are. And, despite it being irrelevant because it seems to be just symbolic, one definitely wonders about the specifics of what she, Justice, and the hab human find or how it was lost. This is not the good “sense of wonder,” which is a shame, as learning about the setting did produce some of the good kind.

“Nexus” by Nancy Fulda

In a universe in which travel between the stars is via portals which kill their users after a few jumps, ten-year-old Tyra has been left in a Refuge on one planet while her parents have gone on to another for work. Miserable in this Refuge, she follows her departed brother’s advice and, accompanied by her strange pet, tries to sneak off to a new world. In the course of this she learns things about herself and her pet that cause a shift in perspective though, for her, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Much like “Justice and Shadow,” one of the strongest elements of this story is the well-realized setting of its portal. The critter is very interesting, as well. Somewhat akin to the other, this story is also somewhat deficient on character (though Tyra’s stock “waif who yearns for change” role is well-realized as far as it goes) and the plot is very simple. It also delivers a rather pat “speechy” ending which is a little simple even for a YA tale (which this is). Still, there is an almost Heinleinian feel to it early on, with the plucky protagonist and it does keep to the theme of humanity needing to change or being changed, taking a different angle from the other story.

“A Lack of Congenial Solutions” by Kenneth Schneyer

Humanity has become a colonialist monoculture before the diverse aliens rise up. The bulk of the story is moral agonizing amidst much discussion about whether to wipe humanity out.

This is a rather New Wavy tale told in a collage of “excerpts,” many of which are in a sort of verse. Obviously, once again, not much can be said of its plot or character or even of its setting, in this case. There is even less scientific/technological thought in this than in “Justice” or “Nexus.” All that’s left is the moral issue. I initially thought it was going to be a True Believer PC piece but something in it at one point made me hope for a brilliant Invasion of the Body Snatchers-style “works either way” treatment in which the paranoia could be about the Communist hunters as much as the communists. But those hopes faded. And at one point, when the story describes the dozen species with the three dozen sexes and multiple means of communication, I thought it was actually going to parody “diversity” and perhaps even have them collapse in bureaucratic infighting or degenerate into internal bloodshed as in the French and Russian revolutions when the “more correct” began slaughtering the “less correct.” But it didn’t do that, either. I won’t spoil exactly what it did do but perhaps some people could consider its message. It’s unlikely to impress too many however and, regardless, it doesn’t especially work as fiction.

“Green Girl Blues” by Martin L. Shoemaker

“Niko” is approached by “Sarah” in a bar on Pederson. The young girl has heard that he does mods and she wants one and a trip off-planet. Mods can be cosmetic or they can be so massive as to essentially differentiate species. And, indeed, our green girl wants to reverse the mods that have been done to her people (chloroplasts in the skin so they can survive the farming-poor world of Pederson) and escape to a new world where she can blend in. Problem is, modding is highly illegal on Pederson (supposedly until their gene pool stabilizes but, it seems, really due to corrupt Powers That Be who like to control their working populace) and there’s also a very active customs cop in Niko’s vicinity. Worst of all, Sarah shouldn’t know what he can do. So there’s a leak somewhere. Perhaps playing along with her will reveal how she came by her information.

This is a fast-paced and reasonably entertaining story but, gene mods and built-in cyberspaces and whatnot aside, it’s a very SF 1.0 story about Humanity 2.0 and has almost the opposite problem of the previous stories: this one does have a plot and seems somewhat disinterested in the theme of the anthology and more interested in a fairly conventional tale of identity revelations and crooks and cops with hearts of gold and so on. It is unfair to compare every story an author writes to some great one he has written and I don’t mean to be doing that here. This is an okay but unremarkable story taken by itself. But, relatively, the gulf between the excellence of the author’s recent “Today I Am Paul” and this tale is very large.

“Mindjack” by Jody Lynn Nye

While on a centuries-long voyage to Alpha Centauri, a crew has been given extended lives, cryonics, enhanced stimuli during relatively brief waking periods, and a sort of computer-mediated psychic connection. The last leads to a premium being put on privacy and the optional nature of mindlinking. So, naturally, two goofball techs with too much time on their hands violate this and turn a woman’s dreams into public entertainment. (You may detect a bit of symbolism there as sometimes writers write about writing.) She and everyone of the next “phase” (or wake shift) is incensed about it. Can any good come of it at all?

This reminded me of everything from a couple of Clifford D. Simak’s 50s stories about proto-VR making long space journeys practicable to Charles Sheffield’s Between the Strokes of Night, with its brilliant scientist working on ways to adapt humanity for the stars by playing with sleep states. But people unfamiliar with the machinery of this tale might find it fresh and it certainly tries harder to deploy technological ideas and to address their social consequences (y’know, “science fiction”) than some of the other stories and achieves a better balance between those aspects. It is nearly crippled by a bit of extreme plotting convenience regarding Chief Engineer Marquez’s appearance on the stage and by the subsequent ease of events but, if that isn’t a problem for the reader, they may enjoy this tale.

“An Endless Series of Doors” by David Walton

In a second (somewhat) YA tale, a guy is looking to put the moves on a cute girl by taking her through the portals that people have been using to travel from world to world for awhile now, but which they still don’t understand. The occasion is a party for the 100th world to be found/colonized. Conditions are quite rough with the planet barely habitable and the colony just getting under way but a special energy dome has been established, powered through the portal, with a full oxygen supply and net connections and other such niceties for the visiting party-goers. And then the portal goes down. Uncertain whether it will ever come back up, the reactions of the two main characters illustrate two very different kinds of people.

As is sometimes the case with theme anthologies, the stories that barely qualify at all thematically are the ones with the fewest problems aside from that. Neither character really exemplifies a “humanity 2.0” in that we’ve had pioneers and stay-at-homes all along and the tech is not directly, biologically transformative or anything. But the characters are drawn succinctly, the plot is simple but effective, and the feelings when the portal goes down are very effectively evoked.

“The Right Place to Start a Family” by Caroline M. Yoachim

Yuna is set on leaving Earth, which she sees as unsuitable upon which to raise a family, and is trying to talk her current guy into going with her. He declines; she leaves anyway. Thus begins a vertiginous journey of millennia in time-lapses between cryo-sleeps as Yuna tries to find a situation that’s just right.

The time-lapse approach once again puts me in mind of Sheffield—in this case, his Tomorrow and Tomorrow. However, the imagination with which Yoachim fills the scenes is different from Sheffield’s imagination and the compression of this short story produces quite an effect. (The effect being, in part, “Whee!”) It’s all wildly implausible and more symbolic and fantastic than literally believable, and it resolves in a way that’s a little too “spelled-out” and sure of itself, but this was quite an enjoyable read and, at that point, made it the story most successful at being both absolutely on-theme and intrinsically interesting.

“EH” by Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

Erik Hamada is a sort of communications officer on the Kaku when word arrives from the lead ship in the convoy that they’ve encountered a region of space in which their junk DNA mutates. Instantly on top of things, Erik realizes that they’ve been given a Rosetta stone by aliens—that their junk DNA has been used to encode information which would only manifest once humanity became extra-solar. Unfortunately, this Rosetta stone can only be read at the cost of killing the person being studied. This doesn’t stop some unstable people from illicitly volunteering, including Erik’s father. Erik descends into a pit of depression and emerges to find that the message has been decoded and that some humans are becoming “Enhanced” (which is one of at least three meanings of the story’s title)—which is to say, initially possessed of greater foresight, but at the cost of blunted emotions and a decline in interest in reproduction, which are only the early stages of the changes. How this is dealt with forms one thread of the story, the changes in both Enhanced and un-Enhanced forms another, and the protagonist’s own personal journey as a rigidly un-Enhanced person forms another.

This is a dense story with many parts in just about 6,000 words and yet is not cluttered (despite the impression the sketch above may give). It does address a changed humanity, and does keep its eye on both the ideas and the characters. In a certain way, it’s reminiscent of Greg Bear’s Moving Mars but, in a more general and central way, it’s a “Clarkean” tale. That can be taken as a compliment and a criticism. Despite the bizarre and far-fetched nature of the premise, it’s something of a hard SF tale, but is that sort of hard SF which comes out the other side and gives way to mysticism and a technology indistinguishable from magic. And, on a technical note, I’m probably betraying biological ignorance here (or missed something in the story) but I’m not sure why the DNA analysis had to be done on living people. They should have been able to extract information from anyone who died after the mutation. Granted, they’ve been engineered for longevity and part of the point was that they were extremely impatient but the story seemed to imply there was no other option as far as obtaining the information. Not to mention that the whole notion of “junk DNA” is handled a little blithely. Anyway, I somehow can’t completely love this tale, but it’s a substantial and interesting one and will likely have great appeal to some.

“The Hand on the Cradle” by Brenda Cooper

In a confusing presentation, it is eventually made clear that a woman, who has been uploaded into a robot and has been a pilot for some time, has been captured by a man who hates “dark” robots and is torturing her into revealing their location (which she doesn’t know). Prior to upload, humans must swear devoutly to obey a version of Laws regarding not lying or harming humans but some—the dark robot-people—have violated their oaths. We are then treated to a litany of torture and, once the robot-woman is rescued, we are treated to another litany of torture. (This is the “catalog of evil in order to stir up righteous indignation” story.) In the end, the woman has a choice to make about whether she is a dark robot or not.

The story opens with the protagonist feeling “small and alone and distant from all of her dreams” which seems to be a cheap effort at enlisting the reader’s sympathy and pity. It then dives into a psychological and intensely written style that is supposed to carry the reader along but, if the line regarding the “small” person hasn’t engaged sympathy (which is rendered more likely if the reader is next perplexed by the bare logistics of the tale) then most of the sound and fury initially signifies nothing. However, if you wish to feel some righteous indignation and are more susceptible to the story (including being unaware, as the author seems to be, that the “good rescuer” is doing the same thing to the protagonist that the “bad man” was), perhaps it will serve to stoke it. On the other hand, the author does tread a contingent, pro forma middle path in a way I won’t spoil which may dissatisfy some who would otherwise like the tale. Those people would probably enjoy “A Lack of Congenial Solutions” more, though even that doesn’t grant all the righteousness for free.

In addition to the nine originals discussed above, there are six reprints which add considerable value to the book (especially as, despite being 2/5 the stories, they are over 1/2 the wordage). The strongest of these is the Varley, which hails from 1974 and, aside from a stack of books in one place and a paper to be signed in another, is not dated and, in fact, fits right in with the gender-bending metrosexual stories of today but for the fact of its verve, enthusiasm, economical and clear exposition, and general fun brilliance.

I would have loved an anthology which contained stories which boldly advanced the frontiers of science fiction with mind-blowing new ideas and served as the definitive statement of its theme. While a new reader’s mind might be blown by many of the stories in this book (which is valuable) there’s little that’s really all that unique. Given that the reprint front has been opened, I might also have liked a historically definitive anthology but there’s little that’s really old, either. I think it’s by design that it goes no further back than the Varley story and does produce a “modern” seeming anthology but this means it doesn’t traverse the eras and publish many true classics. But taken simply as something that’s supposed to be a worthwhile read, it certainly is. While there are several stories with what I see as serious flaws, there’s really no story in here that won’t be interesting to someone and all but a couple held some interest for me. While it does contain more than one story with, e.g., generation starships, cryogenics, longevity, and even pseudo-psi “mind speaking” through technology, the anthology does a good job with variety and balance: there are many stories which take straightforward narrative approaches and some which do not; some that are primarily thematic/symbolic but many which are not; we are given many different types of biological or technological changes, some dystopian and some not; and many different methods of getting from point A to distant point B in both time and space are proposed. Perhaps most importantly, while some of the stories might satisfy people looking for more “post-human” pseudo-SF stories, most will appeal to people tired of such tales. All in all, anyone interested in this anthology’s theme will likely enjoy it.

[Editor’s Note: The link at the top of this review will be updated with pre-order information later this summer, so watch the site to be sure to get your copy early.]

Jason McGregor‘s space on the internet (with more reviews) can be found here.