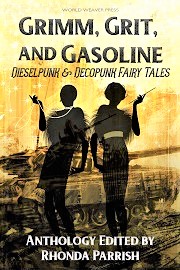

Dieselpunk and Decopunk Fairy Tales

Edited

by

Rhonda Parrish

(World Weaver Press, Sept. 3, 2019, 300 pp., pb)

“Circles and Salt” by Sara Cleto

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

Billed as a volume of Dieselpunk & Decopunk fairy tales, the cleverly-titled Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline offers eighteen new short stories. From grim to gladdening, the stories span so many tones there’s sure to be a mood for everyone. Many of the tales feature women with jobs that disdain “traditional” gender stereotypes, or feature same-sex relationships or both, frequently without depicting the relationships as unusual. Some retell specific traditional tales, some include a profusion of fairy-tale references for humorous purposes, and some situate a fantasy element in a story set in a place and time with the right feel for the anthology.

Sara Cleto’s “Circles and Salt” opens the anthology with a Decopunk tale described as a ‘response’ to the Grimm-collected original “The Girl Without Hands.” More self-reliant than the original protagonist, Cleto’s heroine Elodie responds to her father’s betrayal by finding work in the city (rather than having her needs provided by an angel or an angel-attracted suitor). Elodie doesn’t passively suffer the devil’s schemes while waiting for the attention of a rescuer; when her plan to evade her stalker hits a snag she makes an ally to take the fight to the enemy. It’s worth noting “Circles and Salt” is a response, and not simply a retelling: the protagonist knows the original story because her mother told her about it, and thus knows the techniques its protagonist employs to defend herself. Elodie enters this tale, therefore, armed by her mother with knowledge how to resist. Yet it’s darker: in the original, an impoverished farmer father is clueless when he first puts his daughter in jeopardy, believing rather he has traded away a tree; “Circles and Salt” replaces that dufus coward with a judgmental tyrant who intends (rather than permits) his daughter’s harm. Cleto’s resolution satisfies better: where the original protagonist is saved by angels and her ever-faithful husband, Elodie acts directly. Certainly a case can be made the original protagonist earns her deliverance by Being Good™ in a world set against her, but her strategy of persistent virtue feels passive: whether deserved or not, most of her problems resolve with someone coming to her rescue. “Circles and Salt” features an angry and determined protagonist who executes her own plans, makes her own allies, and works actively to defeat her enemy while finding a girlfriend and starting a band. The story’s differences suit Decopunk perfectly: a woman who responds to the wrongs of men by making her own way in the city and starting a lesbian musical duo feels much more in tune with the flapper aesthetic and their contemporaneous social movements.

Set in the First World War amid the post-battle ruins of Verdum, A. A. Medina’s “Salvage” recasts Pinocchio as a Dieselpunk character. Around a thousand words, it’s not a full retelling so much as an origin vignette. Instead of a lonely old man’s piteous desire for a child, the origin lies with an ashamed survivor’s commitment to make a memorial for a dead youth.

Zannier Alejandra opens the fantasy Dieselpunk “The Loch” on an RAF pilot in the Second World War conducting home patrol in an aircraft that, before being sentenced to spend a century as an object, had been a Captain in the First World War. Since Britain expelled its witches in 1936, it has only the RAF to protect them from Nazi witches who transform into crows to infiltrate, spy, and attack. Alejandra references enough details about Dieselpunk war tech and the world’s fantasy arms race to pique the interest of military fantasy fans and lend verisimilitude to the wartime environment. Inspired by Swan Lake, “The Loch” is a wartime romance in which war isn’t the story’s point but serves to push characters into position and increase their stakes. Fun.

In “Evening Chorus” Liz Donnelly retells Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Nightingale” in a steampunk nightclub. Some aspects don’t change: the Emperor (in the retelling, the owner of the most high-end club in town) has The Nightingale (here, the drab-looking proprietress of a working-class bar) perform for him until he receives an attractive clockwork Nightingale he celebrates as superior, then finds the original singer has disappeared back home; when the clockwork performer wears out and fails, and the Emperor himself is a decrepit wreck, a song from the original restores the Emperor’s health. Fans of steampunk will enjoy the details: the contrast between the glitzy club and the dive The Nightingale runs herself; the description of the technologies and decorations—all fun. The original carries more message: the retelling contrasts glitz and fad with deep quality, whereas the original delivers the same observation while strumming themes about truth and power. Academic differences aside, the retelling delivers a more enjoyable read with more interesting visual details.

“To Go West” by Laura VanArendonk Baugh recasts the folktales gathered in the ancient Chinese novel Journey to the West as a weird short set during the dust bowl. It’s a cool concept, but a reader unfamiliar with the original may be quickly lost, wondering who the characters represent, what their goals are (beyond surviving a storm and an attack), why they behave as they do, and why it matters. Absent this background, the action appears to pose purely physical risks and to have little emotional stake. The fact the characters the protagonist meets are bound to a mission, and have specific motivations that inform their behaviors, would add a dimension of obligation and in the case of some characters lend a note of redemption that would make for a more complex and satisfying experience. In the author’s defense, this Chinese classic is “the world’s best known folk-tale” even if that is mostly in Asia; maybe we should all be better read, and enjoy it better. The weird and magical details are fun, and the tale delivers a happy upbeat resolution.

Narrated by a fairy-on-probation working as a private dick, Jack Bates’ “Bonne Chance Confidential” presents a fairytale mashup depicting numerous children’s stories and fairytales colliding on an isle in Long Island Sound. Bates entertains with a working-stiff’s take on the gritty reality of life in the aftermath of fairy tales. From the area’s backstory (a bent Rumplestilskin tale) to the Cinderella murder mystery, the author gives at least a cameo to probably every fairy tale that came to mind while writing. The result is an unexpected assemblage of entertaining twists on tales familiar enough to enjoy recognizing as they’re referenced throughout the story. A fun time.

Juliet Harper’s “늑대 – The Neugdae ” (“The Wolves”) opens on a Korean girl too small to be put to work in the Army’s camps, whose mother hands her dried wartime rations to deliver to her “Auntie” with instructions to evacuate before she, too, is bombed. The girl wears a saekgongot—traditional Korean garb. It is colored, naturally, in red. Harper bends “Little Red Riding Hood” into a gory Korean War horror featuring betrayal, murder, and bloody vengeance.

Suffused with the detective novel atmosphere of a black and white gangster crime story, Alena VanArendonk’s “The Rescue of Tresses Malone” follows a police inspector who, to do justice in a town too corrupt to allow it, finds himself rescuing Ms. Malone from a crime boss’ lair in the former Tower Hotel. And since there’s something about Ms. Malone he doesn’t have time to learn before his informant is murdered, we don’t know what surprise awaits our intrepid hero. VanArendonk inverts the caper by having the inspector conduct a heist (of a kidnapped future murder victim) against criminals against whom no warrant could be procured from bought judges. No apparent supernatural element. Fun.

Robert E. Vardeman’s “The Daughters of Earth and Air” retells “The Little Mermaid” set during the first World War with a protagonist who is a spirit of earth rather than a mermaid. Instead of being conned by a witch into sacrificing her tongue, the protagonist begs her senior earth spirit to give her a one-way journey into human form where she hopes to capture the heart of a man she saved on a battlefield (else, as in the pre-Disney original, die trying). She isn’t redeemed by true One True Love™ but by her own selflessness, which creates a new opportunity among air spirits (again, as in the original). Vardeman’s retelling is grittier than the original, but preserves the loneliness and helplessness in the face of uncontrollable choices of strangers.

Amanda C. Davis recasts “Hansel and Gretel” as an American tale set during the depression in “Easy as Eating Pie.” Davis doesn’t just change scenery elements, but makes them American: the villains aspire to the entrepreneurial success they’ve seen lift others from poverty. It doesn’t mean they’re not rotten bullies, of course: they’re villains, mean as snakes. A fun read.

Rather than a fairytale retelling, Sarah Van Goethem’s “Accidents are Not Possible” is an alternate history that explains the fate of Hitler and Eva von Braun through the eyes of a twin recruited to repopulate the master race. The heroine, whose powers qualify her to remake Stephen King’s Firestarter, faces a series of personal losses and setbacks only to triumph over her enemies—too dark to be “good fun” but amply rewarding one’s itch to see villains get theirs. Van Goethem builds solid anticipation for the protagonist’s next setback and her response to it, and satisfies on delivery.

Patrick Bollivar’s sets the romp “A Princess, a Spy, and a Dwarf Walked into a Bar Full of Nazis” during the Second World War near a deep, dark forest concealing a Nazi-occupied enchanted castle surrounded by talking wolves. Readers who expect stories depicting military equipment bearing period-accurate names to demonstrate grimdark-accurate operational details would do well to appreciate that Bollivar’s tale is a fantasy, all the way down to the improbable performance of one Sherman against a field of Panzers. Full of fantasy tropes employed or bent to humorous advantage, this short story built in a universe governed by Looney Tunes physics is a fun comic fantasy.

Brian Trent’s thriller “Steel Dragons of a Luminous Sky” follows a Chinese man and an American aviatrix as they defend China from Imperial Japan during the Second World War. Not to be outdone by twenty-foot-tall robots descending from the sky, the Chinese defense includes a clockwork quilin and a mysterious agent from the secret government bureau Luminous Sky. With a battle plan reminiscent of The Phantom Menace, the protagonists set out to halt the robot attack that threatens China. Betrayals and twists lend a heist-like vibe to Trent’s thriller short. Recommended.

Using a framing story set in a parachute factory, Alicia K. Henderson retells Rapunzel in “Ramps and Rocket.” The character names, the heroine’s backstory, and the struggle with the controlling witch are beautifully recast in a crowded smoky industrial setting. The yearning for the love interest and her seeming freedom are beautifully conveyed. The framing story combines with the retelling just as one hopes. Delightful. Highly recommended.

Reflecting cues from Mission Impossible, “As The Spindle Burns” is Nellie K. Neves’ gear-driven fantasy WWII spec-ops heist. Gritty war-story aesthetic is on display from the start: the unit The 12 Huntsmen hasn’t had 12 members in a while. Since it’s a heist, those that remain are divided by personal conflict; one reads waiting for one to knife the next. Betrayals within betrayals and double-crosses spice an improvement upon the original “The Twelve Huntsmen.”

“Make This Water No Deeper” by Blake Jessop leverages Slavic legend to create a wartime romance between a rusalka and the chief engineer of the Soviet hydroelectric dam that disturbs her river, set in the teeth of the Nazi advance westward. The plot is complicated by Russian secret police who plan to bomb the damn rather than surrender it to their enemies. The rusalka, damned to haunt the river where she was murdered by her husband, forever seeking revenge on faithless men, is surprised to find the dam’s Soviet-era chief engineer is a woman. And a good kisser. Jessop’s tale weaves love, sacrifice, and destruction into a wartime fantasy you don’t want to miss.

Inspired by a Polish legend about knights who sleep until needed to defend Poland, Jennifer R. Donohue’s “One Hundred Years” gives a dark twist: the self-help locals undertake when the knights fail to wake. The story’s strength is Donohue’s atmosphere, perfect for a Dieselpunk fantasy quest. The work showcases the protagonist’s reactions and personality, but rather than depict a struggle toward a climactic victory it shows her impelled by the smith’s decision she is worthy to take action.

In about a thousand words, Wendy Nickel crafts a fantasy about the magic of a good memory in “Things Forgotten on the Cliffs of Avevig.” For a bonus treat, one gets exotic vocabulary related to traditional Scandanavian puffin catching. Set on a cliff’s edge and a nearby home, Nickel’s tale works with the themes of withstanding misfortune and overcoming setbacks. Perhaps it’s this reviewer’s weakness for stories about children who manage to teach their elders something real, but the piece feels moving far out of proportion to its modest word count. Highly recommended.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline:

Grimm, Grit, and Gasoline: