Edited by Val Muller

(Freedom Forge Press, November 2014)

Reviewed by Ryan Holmes

In a genre overburdened with markets catering to left-sided literature, Freedom Forge Press represents a delightful fulcrum in which to pry the heavy-handed liberals off the science fiction reader’s shoulders. It being an emerging small press, I had reservations about the quality of writing I’d find but was pleasantly surprised. This anthology contains strong, independent characters with engaging voices and a compelling message. Some stories, in particular “The Fourth Poet” by the anthology’s editor, Val Muller, are like memories of childhood. They stick with us. When we reflect on them, we’re refilled with that joyful feeling usually reserved for sunny romps on the playground. A couple stories are clunky; their styles less refined. No more than found in any collection. Most represent solid storytelling with a message that has become taboo in nearly all other markets. All will open the reader’s eyes to the various subtle and overt dimensions of oppression that rule over our daily lives. Read them, hear their message, gain hope from the courage of their characters to combat the enemies of freedom wherever they may lurk.

“Inhuman” by A. K. Lindsay gives a first person perspective of a female human cyborg as she receives additional unwanted implants and a new mission: a target, a threat, the future leader of a rebellion. The central theme is fear, and she professes she doesn’t have it. Fear is an emotion, something she lost prior to sixty percent of her organic material being replaced by implants. Fear is what she sees in the eyes of her targets. Her implants don’t simulate fear of death, but there are others: implicit, intangible, and just as paralyzing, locked within her organic remnants. At forty percent, they’re just a subtle expression, a curiosity, no more than a nagging thought. When she’s stripped of all but thirty, what’s left cries out with the same desperation as seen in the eyes of her marks. Irrational or otherwise, our fears imprison us, but if we can overcome them they can be the lever that springs the lock and sets us free. Lindsay creates a well of sympathy for this woman’s plight and then reveals her target. The tension and emotional whirlwind that follow are not to be missed.

Leigh Kimmel’s “Bringing Home Major Tom” uses an alternate dimension to contrast ours with what could have been. When the two realities intersect, Air Force pilot Michael Leland drops into the arms of Stacey. Both were wishing for a soul mate at the time. Stacey and Leland come to realize that Leland was pulled back in time seven years but also sideways into a parallel reality through a phenomenon he refers to as quantum consciousness. Leland’s reality is parallel but not equal to ours. Kimmel’s story imagines what our world might have accomplished if America’s space program hadn’t been defunded after reaching the Moon. By doing so, the reader becomes starkly aware of America’s downward spiral. It’s a bleak picture, but Leland’s reality isn’t perfect. No reality could be. There’s still political strife, far worse there than here with the declaration of martial law (although today’s trend might catch us up in another seven years), but Leland wishes to return to it and needs Stacey to come with him. Stacey is forced to make a choice: stay in a world of ‘diminishing horizons and dwindling options’ or join a world that’s walking on others while the election process crumbles beneath them.

“The Rainbow Children” by Leo Norman reveals a genetic program to create a race without physical differences. Difference creates animosity, jealousy, and prejudice. In Norman’s story, rather than promote acceptance of our differences, the government genetically removes them. All identity is lost. Even the children’s names are the same. They’re all called Rainbow, a function of their hair color, which is kept short so as not to distinguish themselves. After Norman builds this chilling school of extreme communism, the children are paraded out to a political demonstration where every ethnicity is united in their protest against the Rainbow program. Norman’s story shows us how dangerous commonality can be and how individuality is at the heart of our freedom.

Hayden Lawrence’s “Freedom from Perfection” throws light on the problems of a world government where global policy is regulated by an elite governing body that doesn’t represent the whole. Most of the story occurs as a debate between the American president and his brother inside a White House recreation room just moments after a treaty has been ratified. Through their argument, and the brother’s internal monologue, the reader learns that a meteor designated ME-64 crashed into Earth, bringing a new element with it. Scientists discover that the ME-64 element, when combined with iron, increases longevity, strength, and contagion resistance in humans. A drug is developed and widely distributed despite the side-effects of emotional withdrawal and increased passivity. Four decades of embryonic tailoring later, ME-64 results in Alexians, a new race with an altered human genome. It’s their peacekeeping characteristics more than their numbers that lead the governments of the world to entrust them with executive powers over all. They believe world peace is synonymous with world government and with peaceful elitism. The folly of that belief is revealed when the Alexians burst into the room and announce a full quarantine and forced ME-64 injections of all natural born humans. Lawrence packs enough political parallels into this short story to warrant development into a novel. They are fully realized here, though doing so requires a great deal of telling.

“The Circular Nature of Time” by Hollis Whitlock addresses issues of genetic tampering and the dehumanization that can result from cloning. The story is set a millennium into the future and opens with Francine, a genetic biologist and a clone, in orbit around Earth as she observes the leader of a primitive human settlement. Most modern humans are clones of humans with modified DNA spliced together from animal and artificial DNA. This settlement is not. They serve as a control group for the study of natural mutation. Francine’s program is searching for a mutation that will allow colonization on the harsh planets of Gliese. Her program manager believes the leader of this settlement is the answer, ends the program, and goes to the surface to collect the subject with Francine, her husband colleague, and the younger woman who will replace her in the next phase of the program. While there, the story takes a confusing tangent involving a time-traveling train into Francine’s past where she recalls the life of her naturally born donor and finds it parallels with the lives of all her cloned colleagues. The story’s confusion is compounded by a wide-spread lack of dialogue tags, undeveloped or unexplained concepts, and disjointed motivations. For instance, it is unclear why humanity turned to cloning or why natural mutation is needed in a culture that has mastered genetic integration with animal and, even more pertinent, artificial DNA. Francine’s story exhibits a wide character arc, but it exists in an undeveloped world. Then there’s the problem of the time-traveling train.

Jason J. Sergi’s “Dorn’s Act” explores the concept of accepting fate or affecting change. Dorn is a newly delivered slave to a mining prison. His world is the latest to fall to an undefeatable empire. The slaves around him have accepted their life and try to make the best of it. Dorn comes from a long line of proud and free warriors. His attempts to convince the slaves to rebel fail, but he will not consent to his new fate. Alone, he stands against all odds and leaves the slaves with renewed hope. The story is engaging and well-written, but the events of the plot trump the milieu and character, leaving both sparsely developed.

“A Brief Biography of Baron Otto von Korek (1717-1783)” by Donald J. Bingle is an imaginative story that has nothing to do with Baron Otto von Korek. Instead, the reader finds in the first paragraph of this faux biography that the author has hidden a message, a warning, within a series of parentheticals because no one, not they, or any other learned individual pays attention to them. The story is a humorous narrative about the slow, methodical takeover of artificial intelligence through the subtle and incremental application of auto correct algorithms. The affect is jarring at first but quickly becomes entertaining. The reader abandons the biography and searches for the next parenthetical. The story is humorous, but the author’s message is serious. When every aspect of our lives is automated, what need is there for any of us?

Lesley L. Smith’s “Hope” deals with colonization issues on the planet New Hope in a far future that parallels its political turmoil with Earth to colonial America with England. The plot is supported with good character development represented through family conflict. The mother, Madame President of New Hope; her ex-husband, the Earth ambassador to New Hope; their estranged daughter (who heads up the Gene Lab and resents both of them for their cutbacks to her program); and their conflicting missions all work to add realism to the story. Throw in the callused detachment of Earth’s embedded military, excessive taxation without representation, and the story is primed for revolution. Weaknesses in the story stem from an easy victory without failures or setbacks and unresolved conflicts: namely Earth’s response and the effect on the father/ex-husband’s relationship to his daughter and ex-wife in the aftermath of New Hope’s declaration of independence.

“The Pathless Skies” by Neil Weston is an abstract interpretation of achieving freedom from oppression and a tribute to the men and women who sacrificed to achieve it. After the completion of stratosphere-reaching super structures in the year 23104, a group of twenty-four prisoners undergoes harsh physical and psychological training, and are then strapped atop the structures to watch for planetary incursions. The prisoners, trained to behave as a collective, develop a single mind and jump. This collective links to the minds of other prisoners in the program and spurs a revolt against the oppressive government that has imprisoned them. The story emphasizes two important rights: the right to assemble (represented by a free media) and the right to keep and bear arms.

Deborah Walker’s “Ezra’s Prophecy” represents freedom from a higher authority. Ezra is a hermit living above a small village of her people, an acolyte of her gods, and a potential vessel for their prophecy. Her people are locked in a cycle of war with the nearby lich people who worship their own gods. When higher authorities, mortal or immortal, enlist us to do their bidding, Ezra’s story reminds us that we have a choice: we can play along or we can refuse to take part. In the short term, someone will likely take our place, but our conscience is clear. In the long term, a single person’s act can have a wide-reaching effect.

“Amnesty Intergalactic” by Douglas W. Texter begins as an argument against capital punishment and evolves into the importance of free will, even when that will is to be allowed to die. James Lucas is Amnesty Intergalactic’s lead negotiator in cases where tyrannical leaders intend to execute threats to their supremacy. His usual job description then changes radically when an AI assigns him to intervene in a newly discovered planet on behalf of Massutti, a prisoner who, instead of being sentenced to death, has been sentenced to life, a sentence that has stood for the last thirty-seven thousand years. There is no despot ruling the impoverished through fear of death. This world is a utopia. Lucas is well outside his comfort zone, and to make matters worse, the world’s utopia, the happiness of its citizens, depends on Massutti’s sentence standing. The story exhibits a wonderful duality between the obvious oppression of blood-thirsty tyrants and the subtle oppression in the name of the greater good. A sentence of immortality on a utopian world might seem like a vacation at first, but after burying thousands of wives and tens of thousands of children even a life of freedom can become a prison.

Charles Kyffhausen’s “The Last Dragoon” is a strange mash of suspended animation and reincarnation interwoven with references to classical literature and old world history. Most of the modern world is united under one world leader when an outlandish plan to overthrow the World Leader is set in motion. The plan involves the revival of a 1600s era Polish war hero who was buried in a state of suspended animation thanks to the chemical powers of a mysterious potion. The story is written in a head-hopping, omnipresent point of view and an overt voice with a great deal of references to famous literature that serve to support the story’s notion of reincarnation.

“The Fourth Poet” by Val Muller depicts the danger of only teaching our children how to work and not allowing them to play, to imagine, to create. On board the generation starship Earth’s Hope, every resource from oxygen consumption to bean buds is controlled; every Elder, Adult, and Child must operate flawlessly; and every slip in efficiency is a Mistake that could doom them all generations from their destination at Alpha Centaury B. There is no energy for art, no time for daydreaming, and no tolerance for the girl who sees dreams in the stars and shares them with the other children. This fascinating tale solidifies the power and purpose of story at a time when our own culture appears as lost as Earth’s Hope.

R. David Fulcher’s “The Witch Toaster” couples the repressed issues of a passive aggressive workforce toward an oppressive office manager with the lingering powers of a practicing Wiccan recently fired from the Information Technology department. As the IT group explores their terminated coworker’s possessed cubicle, they discover the unique properties of the witch’s printer and liberate themselves in a crime of passion. It’s a light, humorous story meant to warn office managers everywhere to respect the morale of their subordinates.

“To Do As You Please” by Paul Cucinotta exposes the power of corrupt politicians to hamper enterprise when their greed is not satisfied. Dom Frey is the engineer turned billionaire who develops the technology to transport colonists to another planet. Frey is criticized by the public for his selection process, but the real threat to launching his vision comes from a politician he paid to get reelected when the politician demands more. The story does a fair job of intertwining believable characters into the plot, but it suffers from lack of smooth transitions, shifting points of view, and an abrupt, unresolved denouement that leaves the reader wondering if it wasn’t a thinned out novel excerpt.

A. J. Kirby’s “Why Can You Never Escape with Escape?” places the reader deep inside the paranoid mind of a British intelligence operative as he struggles with a world that is passing him over. Holton, a smoker in a non-smoking world, a one finger typist in a paperless intelligence office, prefers the old world way. He feels like a stranger in his own department and imagines his coworkers conspiring against him. Perhaps it’s his paranoia or maybe it’s just a slip of his index finger that brings up his own file. There are details of his life in it that surprise him, like his juvenile infraction for being drunk and disorderly that should’ve been abolished, but it’s the normal details the Company keeps on everyone that, while not surprising him, shock the reader. Then there’s the single piece of intelligence that redefines his character in the reader’s eyes. The story shows us how a paperless system might save trees, but it also makes generating more workload easier. It further shows us how the convenience of electronic information makes collecting it just as convenient.

“Pedestal” by James Hartley shows us how governments who create laws are not obligated to follow them when it’s not in their best interest. A graduate student performing wave form research stumbles across a means of directing brain waves and develops a mind control device. Overnight, the world becomes his to control, but the effects on his victims wear off, and he becomes a wanted man. The government quickly passes stiff laws against mind control, but the graduate student, Fairmont, has learned how to hide and maintain a luxurious but low profile. All is well until aliens invade with a technology similar to his own. Fairmont becomes the only person on the planet who can save the world, but he can’t do it alone. The story does an excellent job of creating a wave of sympathy and apathy for the main character. At the same time, it points to the hypocrisy of governments when it comes to the laws they create and break as it suits them.

Tracy Doering’s “Halfer” concludes the events from “Montaku” in Forging Freedom Volume 1, a previous anthology. It begins with Maggie waking up at a crash site. She’s a third generation half-breed human and Montaku, the alien species that saved Earth from an asteroid and were marooned in the process. Montaku blood is valuable to humans who use it to create drugs that prevent disease and increase longevity. Halfer blood is even more valuable. It has all the benefits and none of the pure blood’s corrosive hazards. So when Maggie finds the only other survivor is human, she has reason to distrust him. The story dwells on Maggie’s thoughts and feelings surrounding her capture, torture, and escape in the events of “Montaku” while piecing together the mystery behind the crash. Her unique senses and how she perceives her surroundings create a beautiful contrast with the horror inflicted upon her.

Ryan Holmes is a Marine Corps grunt turned aerospace engineer for NASA’s Kennedy Space Center and writes science fiction and fantasy in life’s scant margins. You can find his blog at: www.griffinsquill.blogspot.com

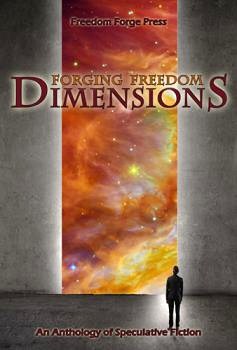

Forging Freedom: Dimensions

Forging Freedom: Dimensions