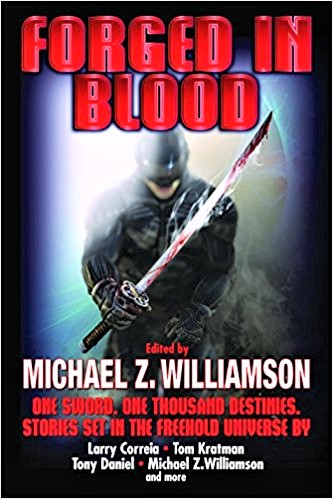

Edited by

Michael Z. Williamson

(Baen, September 2017, 390 pp., hc)

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

Michael Z. Williamson’s Forged In Blood anthology presents thirteen authors’ new stories set in Williamson’s science-fiction (and military fiction) Freehold universe. Freehold stories depict badass women who, whether as soldiers or spies, kick ass when they’ve got to. The sheer number of fans who adore the Aliens characters Vasquez and Ripley show the public hungers to enjoy a badass woman taking care of business. An anthology full of such stories has got to be a crowd pleaser. While you wait for your copy to arrive, may I recommend watching Geena Davis starring as a knife-fighting super-agent in her shockingly under-viewed yet totally awesome Long Kiss Goodnight? As an appetite-whetting exercise.

The sixteen pieces each relate both a story about someone who held (if not exactly wielded) the weapon that threads them together and a fragment of the sword’s own story as it carves a bloody and heroic trail from feudal Japan across the stars. In the anthology the reader will find same-sex relationships, interracial relationships, relationships across religious barriers, relationships that cross class boundaries, relationships between soldiers and those who live in the war zone where a soldier settles, a poly relationship, and characters who display no interest at all in relationships outside the context of battle. Unsurprisingly, some of the individuals and relationships are referenced with a pejorative epithet by at least one character. Those sensitive to casual insult should be warned accordingly. Readers who don’t like military stories should be aware the entire anthology consists of stories in which individuals solve problems with violence (or its threat) in a world in which sweet-talking is inadequate to the present threat. Fans of the United Nations should be aware (a) that the anthology’s stories depict it, when it appears, as exactly the kind of incompetent actor that it is regarded by many who have seen its works up close while serving in other military forces, and (b) that interstellar travel and high-tech equipment neither improves the U.N.’s record in spreading peace or prosperity, nor tempers its reputation for exacerbating conflicts in the vicinity of its resources. The anthology does not uniformly depict a military establishment that lionizes effective killers by recognizing the brutal reality of the circumstances about them, but when the establishment does not, the remaining protagonists disdain this failure as a fault. The anthology celebrates soldiers and their tools. If the premise appeals, buy it: the work is a job well done. Several of the pieces contain an enjoyable additional dose of humor. Because the stories all contain the sword as a linking element, each is strengthened by its location in the anthology, which will provide readers the additional history on the sword that gives each succeeding tale that much more color. Some, like “Broken Spirit,” owes its excellence to the reader’s prior familiarity with the sword and should really be read in this anthology. Unlike many anthologies involving works by other authors, these all appear in chronological order; one ought to read it straight through in the printed order. Together, the pieces in the anthology are mostly winners; I recommend it to fans of military fiction, sentient swords, and military/kungfu mashups.

Zachary Hill’s “The Tachi” appears to be the origin story of an antique sword that becomes known (for a while, anyway) as The Handless Poet. The tale opens on a manor in feudal Japan after it has been surrounded by an enemy clan and before the final engagement, and follows the lady of the manor who responds to her duty by preparing a defense she feels unworthy to mount. The driven-by-duty motive will be familiar to anyone who’s read other work depicting samurai in feudal Japan, from Clavell’s Shogun onward. However, the self-criticism and self-doubt that plague the protagonist feel more like tales the Japanese themselves pen about the era, crafted to explore the frayed edges of samurai values and character. The protagonist Kitanosho knows she’s doomed when she starts—but rather than follow the easy path and telling herself she’s a hero for ordering everyone to die defending the manor, she tortures herself internally, convinced she’s pretending virtues she lacks. But she’s a hero: she knows she’s doomed and stays the course, sure—her clan is samurai—but she does it because she’s trying to defend her home. She’s not looking for honor in death, she wants to see her husband again. She wants to win in this life, not in the next or in memory. So she fights. Not because she sets out to prove something or overturn the status quo—but because she refuses to surrender her home. There’s no rescued-by-ancestral-spirits moment, and no cavalry saves her by riding over the hill at the crucial moment. There’s no moment she discovers battle is just like practice and it gets easy; and she doesn’t get through unscathed. Repeatedly, Kitanosho’s effort falls short in the face of her opponents, numerous and skilled, and she faces the choice to quit. But she’s a hero: their defining trait is they don’t quit. Even when their tools break. One wonders whether the titular weapon—Kitanosho’s grandfather’s tachi—appears centuries later, reforged, in some Williamson novel. In either case, it re-appears in the anthology as the thread that ties it together. This story about a Lady who earns her rank is a good read, recommended. (Note that although the story is recommended as “F” there is no fantasy element in the story except the sword itself; no human notices the sword displaying fantasy characteristics, and the only text suggesting the sword’s sentience occurs after the close of the main story arc.)

Larry Correia’s “Musings of a Hermit” describes a curmudgeonly ronin descended from a one-handed matriarch whose legendary sword he inherited from his father, who doubted him worthy of it. He kicks ass not on the order of a lord, but despite having given up on the duty-and-honor life to live on his own at the edge of civilization. The protagonist’s perspective on his life feels like it’s an outsider’s—not just in the sense that he’s abandoned the society that raised him, but because he comments with an anachronistic libertarian perspective on samurai life and feudal Japan’s social demands and expectations. There’s humor in this—it’s a fun read—but it’s not the humor one might expect in a Japanese story with the same setting. Correia’s story celebrates heroism that goes unsung: not the showy, grand climactic battles that form the stuff of national legends, but the everyday lifesaving work that sometimes must get hidden to avoid being stamped out by the powers that be. Especially enjoyable are haughty and corrupt high-status officials who abuse their power … briefly.

Michael D. Massa’s “Stronger than Steel” is set predominantly over the course of a 1904 battle in which the Russian Empire defended Port Arthur from advancing forces from the Japanese Empire. It’s presented as parallel accounts from a Japanese officer bearing a family sword and a Cossack charged by a Russian noble with overseeing two young Russian officers who are his sons. The Cossack also inherited a sword: an ancient and storied sword with an unusually long handle, with which the reader has already become familiar. The story’s multiple conflicts pit characters’ priorities against one another, with stakes and pressures ratcheted up by the stakes of the conflict that surround them. It also depicts high-status youths being chaperoned by a “servant” with martial expertise his masters will never match. Like many modern war stories, it does a powerful job of showing the humanity of individuals on both sides of the battlefield. Since both nations are run by autocratic dictatorships, neither side has a strong claim to represent anything the reader cares about: the piece is all about the effect of war on those who find themselves duty-bound to execute it. Tragic and painful. If you like military fiction, this one is for you.

“He Who Lives Wins” by John F. Holmes alternates between an American and a Japanese perspective on an engagement in Guadalcanal. This piece uses switching perspective more to build anticipation and explain facts the Americans wouldn’t know than to humanize the protagonist’s opponent. Unlike earlier chapters in the sword’s history, this one shows a character arc: the protagonist makes decisions that prove he’s changed. Its language will be familiar to fans of modern military fiction because it’s set in an era of Colt 1911s, Browning automatic rifles, Thompsons, and other equipment from the modern era. So, a double-threat.

Rob Reed’s “Souvenirs” picks up on the old sword’s tale to show it passing between owners who don’t know one end of a sword from the other. The main action is told in flashback, a story within a story. The theme of individuals forced to take a stand against bullies—present in the earliest stories about the sword—returns with more force than in the earlier stories set in modern battles. In the denouement, Reed shows that both the sword’s story and its last owner’s have been reduced to forgotten tales, lost forever, unrecoverable—a fate that befalls so many who have done so much for those who needed them when it mattered most. Reed conveys the pit-in-your-stomach sorrow of stories swept away, forgotten, assumed to have been worthless. This aspect of the story is beautiful for its awfulness, completely eclipsing what appears to be the main story arc.

In “Broken Spirit” Michael Z. Williamson and Dale C. Flowers join to write what opens as a tragic crime of hamfisted shopwork on a piece of carefully-crafted steel art. The authors understand what they’ve perpetrated: the sword loathes its treatment at the hands of this Pabst Blue Ribbon drinking fool who thinks it improves an antique firearm to chrome-plate it. Anyone who cares about tools … or art … or history … should twitch. This piece is more about the sword than prior pieces, and about its personified reaction to its abuse by its new owner, whose demise is the piece’s highlight.

“Okoyyūki” by Tom Kratman takes the story about the sword further: the protagonist not only talks to the sword, but hears its answers. Whether the protagonist is nuts or not, the piece is hilarious; his conversations with the sword are the story’s soul. At least, unless you are into gore porn. In that case, the protagonist’s single-handed katana assault on four (4) T-72 crews, deafened by the sound of their idling tanks, are going to make your day. If any of this speaks to you, you do not want to miss this magic-sword-meets-tanks slaughterfest romp.

Michael Z. Williamson and Leo Champion set “The Day the Tide Rolled In” on a near-future Pacific island caught between its dreams of independence and a UN desire it be unified with its neighbors, ruled by a despot. The protagonist, a retired Marine, leaves his merchant marine vessel to volunteer to protect civilians from an organized invasion. The locals, a colorful polyglot, join the defense without regard to age, gender, or prior training. The story is strong as military fiction, depicting plausible elements like improvised communications, scrounged weapons, ammunition shortages, fled allies, peculiar injuries, and so on. When the sword appears, it doesn’t speak to its owner: this piece departs the land of fantasy for a more traditional military fiction with a modern-day feel despite its future date. The future, apparently, doesn’t arrive everywhere at once; the battle space is full of scrounged weapons with origins that can date back a few wars. “The Day the Tide Rolled In” has enjoyable action and a sympathetic protagonist, no discernible F or SF elements, and a conclusion well-suited to the story problem and the protagonist. An enjoyable read.

Peter Gant’s “Ripper” brings to an alien planet the sword that links the anthology’s tales. The title is the nickname of a local predator, one of a vast teeming ecosystem fearless of humans it reckons in the middle of the food chain—fair game to stalk and eat. The colony-builders’ security team has its hands full, especially while effective weapons remain buried aboard their starship behind containers of priority landing materials. Elements like improvised defenses, inadequate equipment, supply delays, and unreliable discipline give a realistic feel to an offworld battle to establish a community in a hostile wilderness teeming with hostile wildlife. Fans of Alien’s Vasquez will enjoy the protagonist’s love interest advancing into battle with a sword to save her overwhelmed paramour.

Christopher L. Smith’s “Case Hardened” opens in media res on the death of soldiers in a vehicle jumped by locals with rockets. Set further into the future than the prior story, it has more a feeling built of elements familiar from stories set in modern times: under-equipped in a hostile land; running for one’s life from pursuit; stealing food to survive; capture and humiliation in low-tech makeshift confinement. “Case Hardened” returns the fantasy element with visions of an Asian woman clearly intended to be the disapproving spirit of the sword, disgusted with the protagonist’s cowardly conduct. Then it’s full-on Kung Fu Theater, complete with time slowing for the hero, and bullet-parrying. Once he’s in contact with the sword’s spirit, and has supernatural combat abilities, the protagonist decides battle is fun. Why did he ever fear it? This redemption romp entertainingly offers humor (including a Monty Python reference), military reports dominated by intentional oversight, and another chapter in the evolution of the sword from an old hunk of steel to a glinting goddess of death.

Jason Cordova’s “Magnum Opus” depicts a high-stakes diplomatic event that disintegrates into a hostage rescue. The gay protagonist avoids scrutiny in a diplomatic event that forbids armed security personnel by pretending, to the hosts’ discomfort, to be the mabassador’s lover. Rather than being the ambassador’s interracial homosexual paramour the protagonist is a top-level secret agent trained in special warfare! Cordova gives an SF battle-medicine explanation to the accelerated-time experience the sword’s last users enjoyed in combat, so the overall feel of the piece is more SF than F. The kung-fu climax is fun, the heroic death glorious, and the story easy to enjoy. Readers who demand character development or hard climactic choices won’t find it; it’s designed, rather, for readers clamoring for a kung-fu flick starring a pre-Craig James Bond. That, it delivers.

Tony Daniel’s “Lovers” depicts a war zone romance. It’s not a happily-ever-after story: it opens as a letter from a friend of the deceased NCO protagonist to her parents. The story is delivered in alternating voices: drafts of letters to the deceased’s parents take turns with close-third accounts following the deceased (and, in the denouement, the letter’s author). The letter segments initially seem to create distance from the action, but as later drafts show their writer changes his mind what to send them they become a window into his private thoughts, his anger, the entertaining things we understand he wants to shout, and the words that on consideration might be more appropriate in a letter to a deceased soldier’s parents. Although the story depicts an offworld conflict, it has the feel of current engagements: sectarian factions divide civilians and identify targets for the butchers fighting to control the land they live on. Even proper nouns give a Middle Eastern feel, which risks dating the piece even as it evokes the gritty reality of existing conflicts embedded within civilian population centers. Daniel shows few characters, and their thoughts lie much more with their immediate human relationships than the large-scale forces that shape their lives. The protagonist’s chosen family is much more a family to her than her parents. Events outside characters’ control critically shape their lives: where rockets fall influences who’s orphaned, who’s lost, who’s propelled to revenge. Daniel’s story evokes sympathy with those who survive forces they can’t control and must live by their wits while the witless or abusive masters of local resources squander individuals’ opportunities for happiness. It’s a love story and a revenge story and a tragedy, well worth reading.

Set on the planet to which the protagonist fled after being framed in connection with an embezzlement scandal involving U. N. logistics, “The Reluctant Heroine” by Michael Z. Williamson returns the anthology’s sword to use against humans in a pitched battle that runs its participants out of technological intelligence (thanks, EMP bursts!) and eventually out of ammunition. Resourceful frontiersmen repurpose mining technology to destroy enemy command and control elements. No fantasy elements appear, and the battlefield technology—surveillance drones, mines, data-display helmet visors—seems almost too near to view as SF elements. It’s military fiction set on another planet, and the decisive element of the battle turns out to be the UN officers’ incompetence when their communications are removed. While it’s all well and good to poke fun at an antidemocratic organization that exists to make politicians feel good about themselves, it’s somewhat disappointing to read that a professional military was defeated because its officers, despite commanding more troops with better equipment, put their lower lips out and wept when their umbilicus to instructions was cut. Maybe the point of the story is to comment on U. N. military culture (or lack of it) and its inherent opposition to the kind of culture that makes military forces effective. If so, it’d have been easier to sell with some story told from the U. N. side, to show why they were culturally unprepared to take local responsibility when the command pipeline died. A story that victory followed commitment rather than technology is an easy sell, but convincing a reader that a professional military with the power to project force to distant planets fails to train and develop competent battlefield commanders, and continues to fail to evolve competent tactical leadership over the course of an interplanetary campaign, is harder to sell. They’re humans too, and humans have a track record of resilience. Information about the invading forces’ short tours preventing the development or retention of institutional expertise, or something, feels necessary to swallow the premise behind the victory. That said, the protagonist’s navigation of the battlefield, the delayed realization of injuries, the various mounting equipment issues, and the erosion of supporting forces from attackers’ incoming fire all had a plausible feel. The descriptions allow a clear image of the scene witnessed by the protagonist, complete with the disastrous revelations about her commander’s plan to attack incoming forces at a spot from which she’s unlikely to be able to remove her troops. It’s vivid and fun. I just wish the explanation for the victory had been sold more convincingly.

Michael Z. Williamson’s “The Thin Green Line” depicts active and former soldiers at a conference on the world in which “Lovers” was set. The conference involves soldiers in ceremonies, exposes them to admiring cadets, and involves presentations the content of which appears unfairly to judge and impugn the successful work of some of the soldiers present at the conference. It’s not clear why, other than for service points, the protagonist is present. As the security situation deteriorates around the conference, one hopes something will finally involve the protagonist’s party as more than irritated spectators. Entertainingly, veterans eating while an attack made noise nearby accelerated the speed with which they ate … till the violence quelled. Can’t let the inconvenience of an attack stop dinner, can you? Local Islamist murderers eventually kill enough people rioting and destroy enough stolen Embassy relics on streaming video that the protagonists are invited to volunteer to save the Good Muslims (misogynistic but not genocidal; I don’t make this up, I just report what I read) and the story feels like it begins. There’s a feeling of Old Soldier Saddles Up Again, and even some Crippled Veteran Straps In For One Last Fight. As they unload the guns from their aircraft and reorganize the indefensible position’s defenses, anticipation builds for the gore porn. The embassy is no fortress, has few defenders, and is beset by twenty thousand screaming fanatics with rams and ladders. If this is your thing—and especially if you share the author’s feelings about sectarian conflict in the Middle East—you’ll not want to miss “The Thin Green Line.”

“Family over Blood” by Kacey Ezell is a first-person account of a spacecraft boarding action gone wrong. Playing Watson to his captain’s Sherlock of blades, the narrator describes the protagonist’s conduct—though not her inner thoughts—as she responds to the ambush that awaited their attack and progresses through the ship cutting a swath through the warriors. The beef-for-brains narrator offers comic relief while providing perspective on his Captain’s persistent efforts—first, to keep him alive, then to win duel after duel against the aliens who seem more than happy to put down their high-tech weapons to engage in melee combat to pit their blades against a human’s. Ezell’s humor ranges from the slapstick (narrator zapping himself unconscious on alien electronics, inadvertently revealing a method to create advantage aboard the enemy ship) to the risqué (imagining the attention shown him by his captain—a woman—as implying interest that extends rather beyond his mission utility). The Captain’s own viewpoint—her judgment and her humor—come through clear when she means to be understood, and the reader never wonders if they’re missing something they need to know. The piece exploits emotional range to make its final point: after virtually the entire piece alternated between humor and space kung-fu, it concludes on a serious note about military family. Ezell’s piece is one of the lead reasons one should buy this anthology.

Michael Z. Williamson’s “Choices and Consequences” acts as a denouement to the anthology’s chronicle about a sword remade over and over through the ages. It’s hard to write much about it without spoiling it, but the next owner has the advantage of futuristic technology and historical experts to delve into the sword’s provenance and discern enough of its history to bring the blade from anonymous obscurity. A blade in use from the dawn of the Iron Age should be in a museum, right? As it happens, that’s for its owner to decide. The capstone to Forged in Blood, “Choices and Consequences” underscores the anthology’s recurring theme: celebrating warriors’ decisions to advance into the enemy. It also brings to a conclusion the short segments from the sword’s point of view that appear between—and sometimes amidst—the other stories. Most of all, it celebrates warriors and the stuff that makes them so—the mettle more than the metal.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

Forged in Blood

Forged in Blood