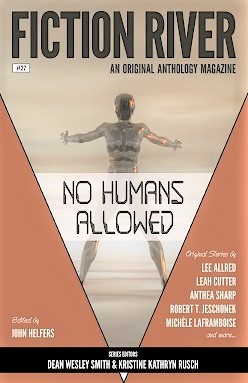

Fiction River #22: No Humans Allowed

Fiction River #22: No Humans Allowed

Edited by John Helfers

(WMG Publishing, April 2017, pb, 281 pp.)

Reviewed by Robert L Turner III

“In the Beginnings” by Annie Reed personifies the big bang and the ensuing creation, expansion, and finally contraction of the universe. The text is a combination of wondering self-discovery and anxious doubt. Starting with the first instants of self-awareness the universe must confront its literal dark side as well as the consequences of the creation of life and the final return to a superdense mass. The way in which Reed is able to balance the tensions between light and dark as well as her rewriting of the beginning of the story in the final words is clever and interesting. While not groundbreaking, the story is clever with moments of pathos and interesting turns.

In “At His Heels a Stone” Lee Allred writes from the viewpoint of a boulder left over from previous glaciation and now, thanks to human interference in the muck near Bosworth Field. The story is built in two parts, the first develops the perspective of the stone and its anger at the ephemeral humans who despoil its realm. The second, is its observations of the battle of Bosworth Field and its actions to defeat Richard III. The story has its moments, but the two portions of the story don’t link together well enough for my liking. I found myself disinterested in the stone and its anger as well as its interaction with the larger world. I think that some readers will enjoy it, and the writing is solid, but it did little for me personally.

Robert T. Jeschonek takes us on a completely unexpected journey “In the Empire of Underpants.” In this story, a lone pair of smart underpants undertakes a journey to save its people from a mysterious malady. In a post-apocalyptic world, where only smart clothing remains, the protagonist’s underwear—and boy is it odd to write that phrase—searches for the magic panties which may save its people. The story is radically different from anything I’ve read before and balances almost plausible situations with puns, and whimsical humor. The ending, after the hero defeats the villain, is cute and fits the tome perfectly.

“The Sound of Salvation” is hard to describe. The protagonist is a song on a vital journey before time runs out. Leslie Claire Walker does an impressive job of conveying the sense of urgency, counting down the seconds left until the song, and life ends. The use of imagery is consistent with the tone of the story and everything in the story builds to a well formed crescendo. This is an innovative and intriguing tale.

“Goblin in Love” by Anthea Sharp lacks the sharp sense of difference that marks the previous stories. Crik the goblin is different from his brethren, he prefers berries and cooked meat, and worst of all he loves a water sprite. The story tells of the choice Crik must make when his fellow goblins decide to hunt and eat his object of adoration. Sadly, this story misses the opportunity to really present a distinctive point of view. As the introduction says, “every villain is the hero of his own story.” If that’s the case, then why tell the story of the one Goblin that doesn’t fit? In an anthology that searches for new viewpoints, this story would be greatly improved by telling the story of a normal goblin and really getting into its mind. The writing is fine and the story is decent, but I can’t help but feel that the author lost a great opportunity to tell a complex and morally compelling story instead of the common, “This was actually a good guy” type story.

“Slime and Crime” by Michèle Laframboise is a police procedural set in the world of snails. When a snail is found dead in the sun, two cops, each with their own issues, must find the perp and make the bust. Laframboise does an excellent job of translating the rhythm and feel of the typical murder mystery into the realities of a snail’s eye view. The story is clever and effectively conveys the point of view of the snails and the various limitations and talents available to them. I should note that the focus of the story is the world building and not the narrative, so enjoy it for what it is.

“Always Listening” by Louisa Swann is the story of Val, a sentient bio-mechanical deep space probe, the last of a dying race. Val is a creature of music, sensing electromagnetic radiation as song. Over the course of her long wanderings she finds another artificial construct and makes contact. Swann does a good job of personifying the probe. The language flows smoothly and complements the nature of Val in its smooth progress. The story is engaging and oddly bittersweet.

Stefon Mears personifies a wildfire in “Here I Will Dance.” There is no plot to speak of, rather the style is more of a stream of consciousness spoken poem. The focus is the pacing of the words, the flow of sentences like fire licking through dry deadfalls. Mears provides an enjoyable atmospheric story, pitting the fire against rain and water. This is a fun and easy read, well put together with tight, crafted language use.

Set on a British sloop during the Napoleonic wars, “Rats at Sea” by Brenda Carre is the story of a former temple rat who must save his lady love when his ship is engaged by a larger French boat. The world building and background are interesting, but at times feels rushed. The story is decent, but the pieces seem to fit loosely and the final scene feels forced. Overall it is a short love story with rats. I consider it a popcorn piece, fun to read, but little substance.

“Sense and Sentientability” by Lisa Silverthorne is a mixed bag. Written from the perspective of a robot who has attained self-awareness, the majority of the story deals with Ottotwo’s process of learning about emotion, feelings, and human behavior. While capably written, it is not particularly interesting and feels similar to the many “AI becomes self-aware” stories already out there. The last third or so of the story moves to how Ottotwo decides to act based on what he’s learned. This portion is better, but the story still ends up being somewhat flat.

“When a Good Fox Goes to War” by Kim May is a fast paced, interesting read. Set in feudal Japan, a kitsune (a foxlike spirit) is offended by an aspiring warlord and decides to seek revenge for Lord Akechi’s entrapping him. Entering service on the other side of the conflict the kisune aids the soldiers, fights a demon, and then gains revenge. May does a good job of conveying the setting and feel of a fable in this first person account. Despite the space constraints, the story feels complete and the style lends itself to the way in which fables assume the reader already knows the wider context. The piece is fun and refreshing.

“The Game of Time” by Felicia Fredlund is intended to introduce a fictional world she has created. The story is told from the point of view of the Book of Time and chronicles the accidents that shape the world. We are introduced to the Book, two gods of time, and the chess game that propels history forward. When one of them makes an error in recording the moves, things start to go sideways. The story is interesting and well written and succeeds in creating a justification for the world., although since it is meant to introduce a world, it feels like the conclusion is lacking.

“The Scent of Murder” by Angela Penrose shares the same basic structure as “Slime and Crime.” There is a murder, and scent oriented beings must find the culprit. In this case, a human merchant is killed in Yzantri space (The Yzantri, while not completely described, are an insectile species). Penrose focuses her story on difficulties in communication, both the physical and cultural barriers. While the writing of the piece is quite good, the logic fails. The murderer sneaks into the victim’s ship and erases part of the ship’s memory to hide the crime, but leaves a note and eagerly confesses when caught. I think the desire to create parallels to the abortion debate forced a conclusion that fails.

“Still-Waking Sleep” by Dayle A. Dermatis is a spin on the story of Romeo and Juliet. In this telling, Juliet is a simulacrum who has been created to ensnare Romeo and cause the downfall of the house of Montague. What no one knows is that she is capable of love. The story is well crafted, and the idea is clever. The concept of Juliet as a honey trap for Romeo adds solid depth to the well-known tale and adds some interesting complexity. Additionally, Dermatis has a love of lush language that borders on overkill, but that fits well into the story.

“Inhabiting Sweetie” by Dale Hartley Emery is part of the alien in host body sub-genre and tells of Dje’Eru an emissary to Earth from Gadlostaran. His assignment is to establish contact with humanity on behalf of his planet. Because the insertion process is random, Dje’Eru lands in the body of a five year old and must accustom himself to the new sensations of his host body. To complicate the matter, Bobby, his host, likes to pretend. The story is mildly amusing and does a good job of conveying the challenges of understanding a different language and culture.

Eric Kent Edstrom creates a world where dog-like creatures are forced into a losing battle in an attempt to hold a vital pass in “The Legend of Anlahn.” Anlahn, a low rank craskin, decides to veer from the typical honor bound role of his pack and searches for a way to defeat the enemy without a bloody siege. Edstrom packs his story with magnificent world building while never losing sight of the purpose of his narrative. Although the culture is foreign, the motivations and choices are clear and understandable. This is a commendable piece and the best of the collection.

In “Sheath Hopes” by Thea Hutcheson we are presented with Shukano a three tentacled, four-limbed Cleemlik who needs to stake a claim on a good universe slit in order to pay off some debts. Once he finds a rift into our world, his treasure of silky stockings provides him with some new opportunities. This is a clever piece that combines a strange world with a logical economy and the life of a lonely miner. The world building makes an utterly alien world seem reasonable and logical, if a bit silly.

The final entry is “We, the Ocean” by Alexandra Brandt and takes the point of view of a mermaid/kelpie colony. Humans are unknowingly killing off these psychic, non-gendered creatures. When one of them desires to take harsh action against the humans, it is cut off from the community. It eventually is able to convince the rest to take revenge, but at that point the story makes an interesting twist that highlights the dangers of limited understanding and self-referentiality. The language of the story is fitting for the setting and the author shows surprising subtlety, especially in the final third of the story.

Robert Turner is a Spanish professor at the University of South Dakota with a side line in Science Fiction.