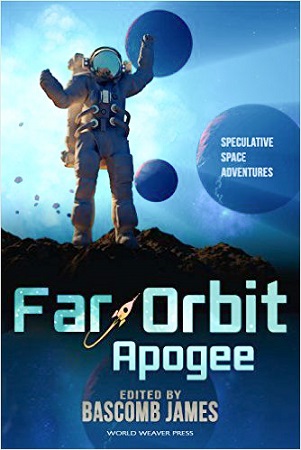

edited by Bascomb James

(World Weaver Press, October 2015, 325 pages)

Reviewed by Jason McGregor

Far Orbit Apogee is the second installment of the Far Orbit series which is “an anthology series dedicated to Grand Tradition storytelling for a modern audience.” Basically, it’s an anthology of neo-Golden Age stories representing a variety of types. Unfortunately, examples include “romance” which has no relation to the Golden Age (in the sense that the word has been traditionally used, as in “planetary romance”) and “genre conversion” which the book mistakes as being a part of “the Grand Tradition” when it was rather a way in which some lesser stories failed to attain to that tradition. The quality level is not really golden, either, being extremely uneven, but there are several decent reads and it does provide a respite from the outright attacks on the Grand Tradition that have set the tone for contemporary science fiction. It is not a particularly political or ideological volume and does not exclude the current arbiters of morality but certainly invites those who might feel marginalized to enjoy more traditional entertainment.

The editor describes each story’s type in its introduction. To provide a quick key to the stories, I’ve quoted or paraphrased these types in parentheses at the start of each summary.

“To Defend and Keep from Harm” by Anna Salonen

(Knight-errant.) An ex-Coalition soldier with a fungus plague which interferes with her breathing and will soon kill her, is in a bar when an old friend drops by with a mission to rescue the child of a Coalition official. The eclectic crew forms up and heads out for adventure. And, in a story with the dreaded enemy alien shapeshifters, of course things will not be as they seem.

The author, here making her first English-language sale, has something to say about lingering enmity (although I can’t specify the vector without spoilers) and ties it to a simple plot which moves along quickly, but the concept/idea, content, style, characterization, and emotional depth did not impress me as meeting professional standards either in a Golden Age or present-day context. I sometimes do revel in unencumbered story and, while I couldn’t here, others may.

“A Most Exceptional Scholarship” by Nestor M. Delfino

(Juvenile.) A teenager is whisked away by an alien to a special school and demonstrates that he has already learned the usual lessons of being nice, tolerant, and self-sacrificing. Interestingly, in stories of this kind, “tolerance” is almost always depicted as “aliens liking each other despite their strange appearance as long as they have the same Christian ethics” rather than anything that would actually test tolerance.

This is a difficult story to evaluate. It does not work at all as an adult story. However, it is intentionally a juvenile and operates under different standards I don’t have a good feel for. My impression is that, despite having a teenaged protagonist, it is more suited for very small children. Less “Robert Heinlein juveniles” and more “Janet Asimov Norby books.”

“Masks” by Jennifer Campbell-Hicks

(Political intrigue.) A prince’s guard must take his place when the prince is killed at the wedding meant to unite two warring empires. Midway into the story, it turns out the prince was himself a stand-in for the original prince, killed many “princes” ago.

There is a pleasing, if predictable, symmetry to this tale but it is awkwardly written (e.g., when the guard is told the truth of the prince’s identity and says he didn’t know (which is obvious), the prince replies, “”No one knows, except for a few”) and the only trace of SF in this medieval fantasy (aside from spaceships instead of sailing ships and planetoids instead of islands and so on) is the magic mask being described as “nanotech.” The mask is made so that it cannot be removed except on the wearer’s death, it makes breathing strange but, rather than protecting its wearer from elements, e.g., poison gas, it actually makes it worse and further helps to obscure identity by modifying the wearer’s voice, which the author doesn’t bother to say. Things like this make it difficult to accept the story. The theme puts one in mind of Robert Heinlein’s Double Star which is, of course, a far superior treatment.

“Murder at Tranquility Base” by Dave Creek

(Mystery.) This is a murder mystery on the moon, involving “memory snips” and implants. Detective Dacia Stark (who has had a previous story in Analog) comes in to investigate when a guy who wants to turn the revered landing site of Armstrong and Aldrin into a tourist trap, winds up outdoors with a well-ventilated faceplate.

One could argue that the mystery was underwhelmingly solved and that some of the science fictional ideas aren’t deeply explored and this would be true, but it’s an interesting quandary in which it’s difficult for the detective to know who’s guilty when even the perpetrators don’t know, and I found it professionally done and interesting.

“Culture Shock” by Keven R. Pittsinger

(Social exploration.) As his final test, a Senior Officer Candidate for the Bright Empire is captured attempting to sabotage the Consulate mining works on a disputed planet. As a “failed” candidate he feels he can never go home. As a prisoner, and following a pledge not to escape or work furrher harm on his captors, he is allowed to move about and is eventually given things to do. The story studies the clash of two cultures and the adaptations one may have to make to survive.

I am favorably disposed to this story and enjoyed it, despite there being at least three things wrong with it: the initial “shock” or clash of values is a bit heavy-handed, the prisoner’s progress is a bit too quick and smooth and, specifically, there is a scene in which the prisoner disobeys an order and, even when trying to translate cultural differences (especially when doing so), I still believe it to be out of character. That said, this is a decent bit of social SF which conveys a sly humor via the bird’s eye view the reader has of narrative strands told from two different points of view, neither of which are themselves aware of the humor.

(I tend to read introductions and such last, so only discovered after reading the story and writing the rest of the review that this is a first sale, which makes it all the more interesting.)

“Lost in Transmutation” by Wendy Sparrow

(Romance.) A human male, attracted to an as-yet gender-indeterminate alien, who wanted it to set its gender to female, understood himself to be rejected when it did not do so and went away for awhile to give both of them some breathing room. As our story opens, he has returned to the alien’s planet to find it has become a female after all (which he believes means she has chosen a mate) but she believes him to have gone off to see his human wife (apparently not having learned in their three-year relationship that he doesn’t have one). They argue interminably. Meanwhile, he is supposedly there to negotiate the release of hostages from local warlords though that is only a distraction and not part of an actual plot.

If I had not been reading this for Tangent, I would not have finished this. It is told in third person but with a narrator who uses slang and sounds rather juvenile; it attempts laboriously to be funny and isn’t, has virtually no plot and is verbose even at its short length, has no emotional authenticity and, at best, one-dimensional characters; and furthermore makes no social, psychological, or biological sense.

Examples of style (partly involving the angry female alien but mostly relating to the protagonist repeatedly imagining his death at the hands of the warlords):

“The doors to the planet slid open. Sure enough, no scent to the air… other than a seething Seetha. Huh. Her name was strangely appropriate right now.”

“Here goes nothing,” Ty said under his breath. If those were his last words, they were lame.”

“She yanked her elbow from his hold and flung open the door. Six months ago, she’d been only slightly more female than him—and, now, this. They were both gonna die.”

“He held back a sigh. So this was how he was going to die. Hopefully they didn’t [sic] do anything kinky with his corpse.”

The intro tells us this was supposed to be a “science fiction romance” because such stories make “the emotional relationships between protagonists the major focus of the story.” It couldn’t have helped if I were, but I was not aware this was the “type” this story was supposed to be exemplifying. Certainly there was nothing else to the story beyond these two people bickering but, as stated, there is nothing “emotional” in it and nothing romantic about a tale full of attempted jokes about “testes” and mistranslating the word “but.”

“N31ghb0rs” by Eric Del Carlo

(Robots/AI.) In a time in which robots have simultaneously (magically) become sentient, one robot, retired from being a waiter, finds himself with obnoxious neighbors and strikes up a relationship with a human who visits the neighbors every ten days for a short time—the only time they are ever quiet. As a fan of mysteries, the robot begins playing detective with the man.

Like several stories in this book, it is heavy-handed (in this case, regarding the initial descriptions of the neighbors), yet never seems clear about where it’s going or what it wants to accomplish aside from bringing the man and robot together. And, while some might like the ending, I found it disappointing. More than that, it didn’t seem all that related to the man-robot connection but was just something that could have been derived from the fiction the robot enjoyed.

“Dainty Jane” by Dominic Dulley

(Bildungsroman.) We open with a girl exposed to vacuum, describing her approaching death in clinical detail before rewinding to how she got there. (A tried and true mechanism, but not properly executed here. How it actually reads is “in space with someone; then in a ship somewhere else with someone” and you can only guess the spaced person is the girl and that the time has been rewound when the scene shifts before confirming it later.) Turns out her dad’s ship has been boarded by a “commerce raider” (read: space pirate) and her dad gets killed. She gets herself spaced and that was where we came in. The rest of the story involves her getting picked up by a man (in the ship which gives the story its title) who has been tracking the pirate, and the two of them teaming up to hunt the pirate down, only for her to find that things are not as they seem and that she has some decisions to make.

On a certain level, and allowing for some rough edges, this was a competently conceived and executed story with some interest. However, as a matter of personal taste, I disliked the ending sequence in the sense that I disliked the protagonist’s choices. While they stretch the idea of plausible behavior, they probably don’t break it and some readers might agree with her and find the ending more satisfying than I did.

“Live by the Ten, Die by the Gun” by Milo James Fowler

(Genre conversion/horse opera.) This story (one of the longest in the book) is a weird hodge-podge of space western, made-up religion, and much more “romance” than was in the story actually labeled “romance.” The plot basically revolves around a space station being a refuge for manslaughterers and other criminals, when a famous space outlaw arrives to exact vengeance on the guy who killed a family member. Except this turns out to be misdirection. The bulk of the story deals with the rekindling love of the middle-aged lady mayor and her sheriff. Another element involves a fake priest and his flock.

This story could never be mistaken for an episode of Firefly and I did not care for it, but fans of space westerns in general may feel differently.

“By The Shores of a Martian Sea” by Sam S. Kepfield

(Terraforming.) For those who don’t have the patience for Kim Stanley Robinson’s length, technical detail, or moral agonizing, but who want to read about terraforming Mars, this might fit the bill. A man is in charge of the project to terraform Mars and the story opens with him complaining about lawyers (anti-terraformers are using the legal system to block the project). Worse, some very inconvenient cyanobacteria is discovered. Worse still, a communist terrorist sabotages the project. The bulk of the tale deals with the struggle between the manager and the saboteur.

There are small problems in this tale, such as the saboteur being a “computer systems engineer” on one page and a “navigator” on another. Whatever her occupation, I find her defensive actions after stealing a ship to be convenient for the manager. There are also larger problems with this tale, such as an improbable and improbably fast terraforming project, though it at least has interesting general dynamics. Many readers may also have a problem with the antagonists and an aspect of the conclusion. But this is actually a story that comes closer to what I think of as the actual “Grand Tradition” than some of the others and I somewhat enjoyed most of it and think many might do the same.

Jason McGregor’s space on the internet (with more reviews) can be found here.