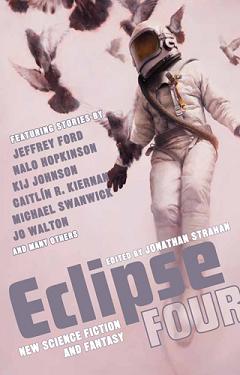

Eclipse 4: New Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Jonathan Strahan

Eclipse 4: New Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Jonathan Strahan

(Night Shade Books, May 2011)

“Slow as a Bullet” by Andy Duncan

“Tidal Forces” by Caitlan R. Kiernan

“The Beancounter’s Cat” by Damien Broderick

“Story Kit” by Kij Johnson

“The Man in Grey” Michael Swanwick

“Old Habits” by Nalo Hopkinson

“The Vicar of Mars” by Gwyneth Jones

“Fields of Gold” by Rachel Swirsky

“Thought Experiment” by Eileen Gunn

“The Double of My Double is Not My Double” by Jeffrey Ford

“Nine Oracles” by Emma Bull

“Dying Young” by Peter M. Ball

“The Panda Coin” by Jo Walton

“Tourists” by James Patrick Kelly

Dave Truesdale reviews the first seven stories and Joseph Giddings reviews the final seven stories.

“Slow as a Bullet” by Andy Duncan

“Tidal Forces” by Caitlan R. Kiernan

“The Beancounter’s Cat” by Damien Broderick

“Story Kit” by Kij Johnson

“The Man in Grey” Michael Swanwick

“Old Habits” by Nalo Hopkinson

“The Vicar of Mars” by Gwyneth Jones

Reviewed by Dave Truesdale

As he has done in several other of his stories over the years, Andy Duncan captures quite well the regional dialect and homespun mindset of his characters. “Slow as a Bullet” is set in rural Florida not long after the depression. One corn-pone character named Cliffert Corbett bets his cronies at the local gas station he can outrun a bullet. Thing is, he has a habit of speaking before his mind catches up to his tongue. Substantial wagers are taken, bets that must be paid either way a year from the time the bet was made. Knowing he can’t outrun a bullet (ole Cliff has a gimp leg), he seeks the advice of the local hoodoo woman. With her advice, and after a year’s worth of experimentation with many a formula for making a bullet travel ever more slowly (using his own brand of logical illogic that would make Henry Kuttner‘s drunken inventor Gallagher proud), the day arrives for Cliff to make his fortune or be proved a liar.

Duncan has crafted a short and amusing little tall tale here, well worth a read and a smile.

Caitlan R. Kiernan has written one of those certain types of stories that brushes up against the possibility of full reader comprehension, but withholds a firm encounter with it. In other words, I didn’t get it. Any true meaning eluded me, perhaps because the piece–while well written (description, imagery, etc.)–had so wrapped itself in a Gordian knot of metaphor and metaphysicality, and was so shot through with various ambiguities that any possible point became lost to me. None of the references, whether from physics, philosophy, or literature, seemed to cohere, to connect in any reasonable manner.

One of a pair of lesbian lovers is engulfed by a dark shadow that has rolled in over the ocean toward the shore, leaving a growing (black) hole in her side. (This is just the token literary/fantastical machina used to set the story in motion–no further mention of it is made; no rubber theories proposed for its existence, etc.). As the size of the hole increases (she feels no pain and is otherwise healthy) we are given continuous references by the unaffected one to space, time, and shadows as she tells her companion’s (and their) story. I suppose there’s some perfectly understandable resolution at story’s close–some sort of emotional closure near as I could fathom–but I just didn’t understand the relevance of it given what had come before.

The next to last line of the story has one of the characters, Emily, telling Charlotte, her partner, “I’m sorry, I say, even if I’m not sure what I’m apologizing for.” Well, if one of the main characters is confused at story’s end then we don’t feel so alone in our perplexed state at this non-sequitorial line of closing dialogue. There is that.

I really enjoyed Damien Broderick’s “The Beancounter’s Cat.” It’s a far-future, post-singularity space opera set on Iapetus, one of Jupiter’s moons. The bean counter, Bonida, works in a “small office” near “the middle of the world,” for the Revenue Agency assessing fines to those who cheat on their taxes (will humankind never escape paying taxes, even in the far future and on other worlds?). One morning she takes in a cat with the name of Marmalade (actually the cat let’s her take him in–we all know cats). Turns out Marmalade is an augmented cat who speaks. He’s also a wise-cracking smartass who knows much more about Bonida than he first lets on.

One thing leads to another and before long Marmalade reveals he is on a mission to deliver Bonida to her mother (whose corpse she saw and touched at her funeral), and her father, who turns out to be the overarching machine god of the planet Saturn, an entity formed by a giant Mbrane built by a human-like race eons before and who have moved on. (I hope I got all of that right.) But why is Bonida now brought to visit her mysteriously revived mother, and why now to learn who her father really is? What’s going on here? All I can say without revealing quite everything is that it involves something about the End of Time, and the role Bonida is asked to play for the benefit of her (revived) mother and (machine) father. Hence the addition of “space opera” to my opening description, for while the scope is only that of the solar system, albeit thousands and thousands of years hence, and not the usual large galaxy-spanning canvas normally associated with Space Opera, the thematic concept is about as grand as it gets and truly does elicit a sense of wonder akin to stories we think of as coming from 1930s-era SF.

Also well executed is the manner in which Broderick draws us into the story’s SF elements, for at the very first in one quick scene we think we are in a world where magic might be the name of the game and not super-science. It’s a slick way of reminding us of Arthur Clarke’s now classic and oft-repeated maxim that: “Any sufficiently advanced science is indistinguishable from magic.” Broderick reminds us of this very neatly here. Especially so because our very first impressions are of smallness, of mundanity, and possible magic, and our final images are of the large, the exotic, and are filled with super-science. The author accomplished what he set out to do and did it quite efficiently, with nary a word wasted. A fun little ride.

“Story Kit” by Kij Johnson reminds me of a few stories I read in any number of New Wave collections in the 1960s. We are given two stories (one from the past paralleling the one in the here-and-now), the former from Greek myth (Dido and Aeneas), and a writer’s attempt–inserted between the ongoing story text–to enlighten us as to what she looks for in her story (is the tone right for this story, what is the theme, was there good sensory detail, etc.) as it appears she is thinking out loud about the story she is interrupting the reader to tell, and as such is a reflective exercise best described as metafiction. The narrator is going through a divorce and is trying to work it out through the writing of this fictional story. I’m sure it’s all very well composed on the literary level, but unless one is intimately familiar with the myths the author references in order to tell the current story, the reader will be hopelessly lost and confused. As was I, because without knowledge of the former what the author is doing with the latter becomes a moot point. This type of story is, I suppose, the reader’s fault for lack of understanding, for if good SF or Fantasy is supposed to write up to the reader, to challenge him, then this one succeeded. Too well, I admit, in my case, because I just didn’t get it, since the story also appears to be as much about the literary “style” or technique used to tell the story as it is the actual story itself. And the fact that the story held no speculative element whatsoever but dealt with the pain of a divorce, merely added to my total disinterest. I hate to be so harsh, but spending reading time in an all-original science fiction and fantasy collection reading about the pain of divorce just doesn’t work for me, regardless of how well its experimental/off-beat style fit’s the theme, or works. Quotidian is still quotidian and mundane concerns are still mundane concerns. “Mainstream” fiction is not SF or Fantasy, folks, and is not why we choose to read a collection such as this purports to be. Kij Johnson is a fine writer. I’m sorry my “mainstream” dart happened to land on her this time, but so be it.

Michael Swanwick’s “The Man in Grey” hardly stretches his intellectual capability with this brief meditation on determinism vs. free-will, who pulls the strings (if anyone) on we mortals, and just what might be behind the veil of the reality we know.

Determinists espouse that we have no free-will, that it is an illusion. Those who believe in free-will as a matter of course believe just the opposite. Then there are those who take a middle road and believe that on the large scale our fates are pre-determined but that we enjoy and exercise free-will on a much smaller scale. Swanwick clearly depicts one of the above philosophical viewpoints (I shan‘t say which), with an illustration of how it would work, employing a quite logical (but unexpected to the eponymous Man in Grey of the title) outcome.

Anyone who has taken a Philosophy 101 course is familiar with these basic positions, and while this piece is pleasant enough, it asks nothing new, nor does it add anything new to the lengthy historical canon of those who have written this identical sort of story before. Minor Swanwick, I am sorry to report, with “The Man in Grey” the only one surprised. (As purely anecdotal speculation which can most likely be attributed to mere coincidence, those familiar with Leo Tolstoy’s classic novel Anna Karenina will recall her fate being the same as that of Swanwick’s vodka swilling protagonist in this story. If intentional, then the reference might swell the egos of those who get it, but it still contributes little of substance to the overworked theme).

Nalo Hopkinson’s “Old Habits” takes the central conceit of Groundhog Day (that of a single day repeating itself) and sets it in a mall. The similarity ends there, however, as she depicts those who have died from various means in a mall as they must live their time and means of death over and over and over…as ghosts. It is rather nicely done for such a brief story, for she has come up with a few rules governing such a situation (which won’t be divulged here but are what make the story interesting), and tells it from the viewpoint of one of the ghosts as he relates the stories of the other mall ghosts and their deaths. When it is his turn in the day to re-live his own death (what the author calls being “on the clock”), we are by then sympathetic to his character and thus feel for his particular situation as two of his living family must watch him die. “Old Habits” riffs on a by-now familiar idea and explores it effectively. For what it attempts to do it succeeds, and therefore a well done is appropriate.

Gwyneth Jones’ “The Vicar of Mars” is set in her popular Buonarotti universe, which she has written about at both novel and short length (the White Queen trilogy, and most notably in stories such as “The Tomb Wife“ from F&SF and “Saving Tiamaat“ from The New Space Opera–both from 2007; these and two others were collected in her 2009 collection from Aqueduct Press, The Buonarotti Quartet). Cribbed from the rear cover of The Buonarotti Quartet because it explains the concept of the stories quite succinctly: “…the reclusive female genius called Peenemunde Buonarotti invented the instantaneous transit device of the same name. [The stories] show us humans traveling via the device to alien worlds and situations. Some are diplomats, some are extreme travelers, some prisoners.” To which Jones now adds the Vicar of the title, vicar being a delegated representative of a religion, and in this case the vicar’s territory being Mars.

The Reverend Boaaz Hanaahaahn, High Priest of the Mighty Void, is of the race of Shet, he of ponderous bulk and grey hide. Finding himself on a Martian mining settlement he is made aware of an old woman who is “suspected” of being wicked and insane, who he reluctantly agrees to visit in the initial hope of merely comforting (not converting) her to his religion of the Mighty Void, of non-belief in an afterlife. What he discovers in the woman’s home is hardly what he (or the reader) expects–including “impossible creatures” and fleeting shadows–and begins a tale that will eventually shake his faith. Pure SF and more than just a colorful adventure story rife with aliens and transport drives, “The Vicar of Mars” is a worthy addition to the author’s previous Buonarotti tales. Solid entertainment and recommended.

“Fields of Gold” by Rachel Swirsky

“Thought Experiment” by Eileen Gunn

“The Double of My Double is Not My Double” by Jeffrey Ford

“Nine Oracles” by Emma Bull

“Dying Young” by Peter M. Ball

“The Panda Coin” by Jo Walton

“Tourists” by James Patrick Kelly

Reviewed by Joseph Giddings

“Fields of Gold” by Rachel Swirsky explores what happens to us when we die. Dennis, who dies after his wife finally agrees to pull the plug on him in the hospital, finds himself in an afterlife where he not only meets people he knew, but also people he never knew. People before his time like Napoleon and Alexander the Great. They all congregate in an afterlife party, where none of these folks are ready to move on yet. Dennis thinks about his life, what he accomplished and didn’t accomplish in thirty-five years, and reaches some startling revelations about his life and his death. As guests move on to other parties, and others just vanish completely, he moves to another party himself, following some of the others, and meets his wife, also dead. They finally lay out some truths they hid from each other, and they both come to grips with the mess they made with each other’s lives.

As usual, Swirsky’s mastery of language and fiction shines through in this story, keeping you reading to find out just what happened to Dennis, and if he will finally decide it’s time to move on. A great story written by an excellent author.

“Thought Experiment” by Eileen Gunn is next in line. Ralph Drumm is lauded as the inventor of time travel, and he thought of it while he was in a dentist’s chair having his teeth whitened. Once he gets home from his appointment, he puts it into practice, and finds himself in the past. 15th century, to be precise. However, he finds he stands out like a sore thumb, despite his efforts to hide that he isn’t from their time. Only when it’s too late, and he’s polluted the time line in a manner you would never expect, does someone look to stop him. Unfortunately, time travel stories of any kind tend to leave a bad taste in my mouth, and this one was no different. Ralph isn’t very believable as a character, even if he does possess a dizzying intellect that allows him to time travel just using his mind and a piece of software that, I think, is embedded into his brain. I found this story a bit too farfetched, even for a science fiction story about time travel.

“The Double of My Double is Not My Double” by Jeffrey Ford is an odd story about how many of us have a double. They follow us around and learn about us, so they can… I’m not sure what their purpose is. At first, we are led to believe it’s normal to have a double. However, when the main character talks about it, he’s given medication to help him stop seeing them, from a therapist. Then, his double reveals directly to him that he has a double as well. And he’s evil…

It lost me completely. Why do these people have doubles? Why do these doubles draw a salary? And live together with other doubles? It’s all just so confusing and lackluster in presentation that I finally just gave up and tried to follow along as best I could. Thankfully, it ended quickly. Don’t think I’m saying it’s a terrible story, for it is well written with some good science fiction elements. It’s just hard to follow and lacking in any connection with the characters.

“Nine Oracles” by Emma Bull follows nice characters from different places and times who know whatever it is they are doing isn’t the best course of action, but they either do it because they have no choice, or do it because they don’t care. None of them are related in any way that I can discern, and in the end, I really didn’t care. Each person gets a page, maybe two, and while it’s funny and sometimes horrifying what happens, it all just feels more like a collection of nine themed flash fiction stories rather than one, cohesive, story.

“Dying Young” by Peter M. Ball is a western gone wrong, feeling more like a Weird Western set in the future rather than the past. The sheriff has clones, the doc has a half-man, half-machine army, and the main character has the ability to see the future. Make the antagonist a human mutated into a dragon and you have one strange story. Well written and fun to read, I ripped through this story in a hurry, the atmosphere created by Ball being engrossing and fascinating. I’m not sure if the Western feel was intentional or not, as I sometimes felt like the author meant for this to feel more futuristic than it actually developed. But this didn’t detract from enjoying the story. Also, while the characters weren’t likeable, I think it was part of the charm of the story as there were no clear cut good guys and bad guys. Just people (all of them with questionable pasts) struggling to survive in a small town and a dragon marching through killing all that he can. One of the better stories in this volume, and easily ranks with my recommended reads.

“The Panda Coin” by Jo Walton is a very unremarkable piece. Like “Nine Oracles” earlier in the book, this story follows many different characters as they pass along a golden coin with a panda bear on it. As it moves through a space colony, we see the different areas within it, from its lowly slums to its higher echelon living sector. I almost expected the coin to wind up back in the hands of the first person who had it, leaving me wondering if the author got their inspiration from a story I once heard where a hotel owner took the $100 he received for renting a room to someone and then that hundred passed around town as people paid off the debts and bills, only to have the money end up back into the hands of the original person who rented the room. However, no such fate was in story for the money. Instead, it just bounced around from one uninteresting person to another until at the end it winds up in the hands of one of the robotic overlords of the colony. I had no complaints about the narrative, but I didn’t find the story to be particularly fun or earthshaking.

“Tourists” by James Patrick Kelly ends off the book, but it doesn’t do it with a bang. We meet Mariska, who is a hero for some unknown event that left her slightly brain damaged. We start with her in a hospital on Mars, where her mother is helping to repair the damage to her brain and working to rehabilitate her. When an emergency in the hospital forces an evacuation, a native Martian named Elan helps her get out, and from there a friendship forms. As we follow the story, we see Mariska struggling to recuperate from her ordeal. Additionally, she has to endure the irritation of everyone knowing her, of not feeling like a hero when so many people died, and she wonders why she is treated like a celebrity, her voice carrying far more weight than she thinks it should. And, as her relationship with Elan progresses, we see that racial barriers will exist even in the future, except it will exist between humans and other races (the Martians used to be humans, but became genetically altered to survive on Mars). It’s a good story that carries a strong message about heroes (or celebrities), racial tolerance, and the importance of family. Sadly, despite these themes, it never really takes off and leaves the reader feeling a bit left out of the loop, like there is a lot more to this story than wound up in the final draft. I wouldn’t say give it a miss, but don’t trip over yourself trying to get to it.