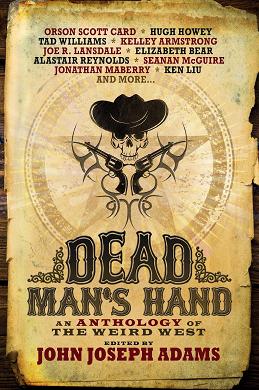

Special Double Review

Special Double Review

(Reviews by C. D. Lewis & Ryan Holmes)

An Anthology of the Weird West

edited by John Joseph Adams

(Titan Books, May 13, 2014)

“The Read-Headed Dead” by Joe R. Lansdale

“The Old Slow Man and his Gold Gun from Space” by Ben H. Winters

“Hellfire on the High Frontier” by David Farland

“The Hell-Bound Stagecoach” by Mike Resnick

“Stingers and Strangers” by Seanan McGuire

“Bookkeeper, Narrator, Gunslinger” by Charles Yu

“Holy Jingle” by Alan Dean Foster

“The Man With No Heart” by Beth Revis

“Wrecking Party” by Alastair Reynolds

“Hell from the East” by Hugh Howey

“Second Hand” by Rajan Khanna

“Alvin and the Apple Tree” by Orson Scott Card

“Madam Damnable’s Sewing Circle” by Elizabeth Bear

“Strong Medicine” by Tad Williams

“Red Dreams” by Jonathan Maberry

“Bamboozled” by Kelly Armstrong

“Sundown” by Tobias S. Bucknell

“La Madre del Oro” by Jeffrey Ford

“What I Assume You Shall Assume” by Ken Liu

“The Devil’s Jack” by Laura Anne Gilman

“The Golden Age” by Walter Jon Williams

“Neversleeps” by Fred Van Lente

“Dead Man’s Hand” by Christie Yant

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

Edited by John Joseph Adams, Dead Man’s Hand offers so much Weird West fiction, you’d hafta discard a pair not to bust twenty-one. Adams opens by explaining its title (for those who don’t play poker) and providing some background on what the Weird West is. Describing its overlap with steampunk and differentiating it from space westerns helps set the genre in the literary landscape for readers who don’t know the pleasure of wondering what things would be like if the Ghost Dance had actually worked. Adams’ introduction also helps readers set contributors in the genre’s landscape. Some introductions are better skipped, but not this.

Dead Man’s Hand isn’t just a fantasy jaunt. Sure, there is some of that. But the sheer range of Weird West worlds set forth between its covers makes it more of an extended tour of a well-curated zoological garden than just a bus pass to a neighborhood park. There’s upbeat high-energy thriller action, and slow dark creepy weirdness. There’s men taking charge, and there’s men helpless while clockwork automata overrun the world. Maybe you have a weakness for tales of men rescued by women – pick from clockwork women or live ones with lightning cannons – but if you want women rescued by men, there’s some of that, too. There’s frivolous adventure, and deep comment about the nature of man. See the Weird West, by ley-line train. There’s space left in first class. (Just, watch for clockwork gamblers: they count cards, all of them.)

Joe R. Lansdale sets “The Red-Headed Dead” in the same world as his 1986 Dead in the West. Dedicated to Robert E. Howard of Conan fame, the tale pays its respects to sword-and-sorcery with a Weird West sixguns-and-vampires adventure. Not the sexy vampires – ugly, awful ones. Bad omens, foul weather, an unkempt graveyard, and a shattered shelter build a horror feel. Sixguns with blessed bullets warn of Rev. Jebediah Mercer’s direct approach to problems over which he refuses to pray.

Lansdale’s East Texas and its malign God support a dark vibe illustrated by the Reverend’s motives: he’s not moved by love for his fellow man or for the God he serves; he fulfills his divine mission because he can’t escape adversaries against which he’s unwillingly directed. The protagonist’s base condition of privation – and his pessimism about the afterlife – make for a dreary outlook perfectly suited to this horror-fantasy. The character’s adverse relationship with a god involved in mortal affairs is sketched as background, but story’s main conflict lies between the Reverend and a vampire newly loosed from a ruined graveyard. Mercer’s background and motivations are not exposed enough in this short story to suggest a more than merely physical conflict with the revenant, which may limit the tale’s appeal to those not familiar with the character or who are particularly attracted to vampires, the Weird West, or horror. When the story resolves – and the protagonist rids East Texas of a ravening menace – the protagonist’s best hope is that his dry matches allow him to build a cooking fire for his slain horse. Readers keen for a dark tale of violence and misery have found it.

Ben H. Winters’ California Gold Rush tale “The Old Slow Man and His Gold Gun from Space” presents Caleb and Crane, whose Micawber-esque optimism keeps them hunting gold well after the easy gold’s long gone. Or is it? Their outlook in working their claim changes dramatically when an alien from the dark side of Neptune arrives to enlist the (seemingly) doofus prospectors in his hunt for food. What food, you ask, suits a Neptunian? And how does he hunt it? Why gold, of course – hunted with a gold gun. Winters pairs an absurd space fantasy built on a gold-dowsing flintlock pistol with a tried-and-true theme rich with Western tradition: gold fever. The result is a surprise and a delight: the gold-gun’s effectiveness launches Winters’ tale, which quickly delivers the horror of greed and betrayal that poisons every bargain between the characters – and looses a hungry, greedy, and armed Neptunian on Sacramento.

Writing as David Farland, Dave Wolverton sets “Hellfire on the High Frontier” in a Wyoming Territory where a supernatural being compels Ranger Morgan Gray to hunt a murderous clockwork soldier made for the Civil War. From its first paragraphs, the tale sews dark themes of regret, human frailty, and impermanence. Gray regrets the bargain that forced him to hunt the murdering clockwork, his fruitless tangle with a skinwalker, and old actions taken under Sherman in the war. By the time Gray confronts the top-brand precision clockwork, he’s repeatedly confronted his own imperfections, the impermanence of everything about him, and regret after sad regret. Even the authority he possesses on paper is unavailable: Gray spends the whole tale beyond the borders of his jurisdiction. Outclassed by all his adversaries and out of his element in a land where his badge means nothing, Gray plods onward not for practical gain but to soothe his sense of justice.

Farland’s dark themes match his dark conflicts and their dark setting. “Hellfire on the High Frontier” pits lawman against foes in a lawless land of skinwalkers, clockwork killers, showgirls, and steam-powered balloons. Gray recognizes his quest’s long odds even as he heads to the High Frontier. A steampunk fairyland full of silver castles, the High Frontier can be accessed only by airship, and only just after sunset – but far from being heaven, its ruined decay convinces onlookers that heaven’s maker died. Although the story paints inevitable change from early pages, it leaves open for a while whether change includes improvement, or admits redemption. When feral angels sling scat from their cages at those entering a gambling hall built in the ruins of heaven, we sense where the world is headed. Farland’s scenic view on a weird land of perpetual twilight sounds with the hiss of angels. Dark and unsettling, Farland’s account of Gray’s doomed cause suits the Weird West to a T.

Five-time Hugo winner Mike Resnick‘s “The Hell-Bound Stagecoach” is a fantasy set on the devil’s coach, in which a handful of murderers decides to dismount early to open a way station. The pace is reminiscent of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit; the action consists of characters entering the scene and conversing. Whereas No Exit reveals a frustrated love triangle and concludes with the twist that each of the damned makes his or her own Hell, “The Hell-Bound Stagecoach” depicts killers politely cooperating in a joint enterprise. Their road to Hell has an upbeat destination: tough souls intimidate the devil into ceding them their own spread to develop, and their venture proves “most popular” – though the coachman’s refusal to stop upon request invites one to wonder things like whether it has any competition, and why the coachman would begin to make stops on what had been an express route. Rather than depict a conflict resolved, “The Hell-Bound Stagecoach” appears to explain the founding of the liveliest saloon on the road to Hell. Although Resnick builds anticipation wonderfully, and the conversation is fun to follow, none of the dead act like they have much at stake; ultimately, their resolution doesn’t rouse to the extent one hopes in a hijacking on the road to Hell.

Set in the InCryptid universe, Seanan McGuire‘s “Stingers and Strangers” opens with a straight-laced academic sharing a train cabin with a circus-trained gunslinger while bound for Colorado to investigate a disappeared swarm of shoe-sized wasps that have not only human intelligence, but the power to steal memories from humans made to host their eggs. The fact the gunslinger is the female lead sets up tensions involving gender-based expectations, the main characters’ rebellion against norms, and the cost paid dealing with those who conform. McGuire’s characters’ entertaining banter lightens early pages while the reader learns about dragon princesses, the Questing Beasts of Arizona, and talking mice from Michigan. Once the action gets moving, one quickly adopts the characters’ zeal to see their mystery solved. McGuire’s tale accelerates into an exciting high-stakes barn burner featuring gunshot wounds, giant bug attacks, memory loss, arson, mind control, and true love.

Charles Yu‘s “Bookkeeper, Narrator, Gunslinger” is narrated by a bookkeeper surprised to discover he’s outdrawn and killed a man in the street. Using, as it turns out, mind control. Welcome to the Weird West. The characters populating Yu’s old Wyoming snark hilariously at each other’s Western-speak until the narrator is drawn unwillingly into a shootout for correcting sloppy grammar. Comical conflict supports an entertaining sitcom-of-a-Western feel: the story is so aware of Western tropes that it ropes the reader into giggling with Yu over, for example, the narrator’s concern about the other characters’ trope-adherence. However, Yu’s tale proves a serious citizen of the Weird West. The reader’s comfort with light comedy becomes an unarmored target for a sudden jab of horror, followed by a knockout punch: the answer to the question what separates protagonist-grade gunslingers from the general population of keen-eyed quick-draw artists, and what the narrator has finally brought upon himself. The resolution, interestingly, follows on the heels of a trope-busting gunslinger woman (whose physical attributes are, trope-bustingly, not described at all). Cue tumbleweed.

Alan Dean Foster’s “Holy Jingle” offers an episode in the adventures of Mad Amos Malone and his steed Worthless. Dripping with occult images, Foster’s tale pairs a man of contradictions – a huge ape-looking thug with expertise in the manufacture of French perfume – with a problem as common as dirt: a man in love. Well, he’s bewitched by something anyway. Foster’s tale delights in wordplay and literary references. An alternate Carson City and its weird inhabitants deliver a powerful sense of setting; the reader easily contrasts the rough-hewn Malone with civilized people, and Carson City in general with the exotic interior of the antagonist’s room in the brothel.

But, therefrom hangs a concern. While not every story need be written in conscious rebellion against sexual stereotypes, “Holy Jingle” includes elements that may render it hard to accept for readers sensitive to gender issues. The madam with an “accent as thick as her thighs” seems belittled over traits that render males merely distinctive. Conflict occurs not only in a brothel, but during penetration, and is followed – due to the miracle of the protagonist’s peculiar cure for possession – by a mid-coitus introduction between an enormous man and an Asian just sold into sex slavery. When the protagonist rolls off, the woman promptly offers her rescuer (more?) thank-you sex. Because, what else could a female character offer? Readers who feel this is not for them may wish to hunt elsewhere in the Weird West.

Fictional sex can offer a satisfactory resolution to some conflicts, but “Holy Jingle” never depicts conflict between the newly-introduced sex slave and her rescuer. No-one’s stood between them but the madam who doubted the protagonist’s ability to pay – and that, before the Asian was freed from the villain inhabiting her body. The feeling of resolution one expects in a fictional sex scene is normally built atop a foundation of adversity and anticipation. But Malone hasn’t been building anticipation for the woman, only for his confrontation with the villain. The sex slave’s tastes and values are never depicted to the reader, only her belief that she’s got nothing else to offer. There’s no sense things are actually going right for the characters when it happens. The story’s real resolution – the reveal that Malone understood a victim’s mumblings as a mispronunciation of a being from Asian myth, directing him to the solution – feels much more clever and satisfying. One wonders if the tale might feel better wrapped closer to the main conflict’s resolution.

Love gambling gunfighters? Beth Revis‘ “The Man With No Heart” recounts how Ray Malcolm – “a betting man” – goes looking for “answers” and finds trouble. Short tempers and a short-pouring barkeep set the feel of the opening-scene saloon. Curiosity over a ‘short feller’’s clockwork spider delights as a motive; Revis’ Weird West doesn’t need a stagecoach robbery or a gold heist to make it interesting. Ray’s surprising sacrifice to pursue the spider’s origins invites interest: what’s more important to a gambler than gambling?

Identity permeates the story as a theme. Ray’s traveling companion can’t tell one “In’din” from another, even to help Ray figure out where the spiders come from. Ray doesn’t know where he himself comes from. But he knows where other people come from – certainly, more than his traveling companion. Although Ray is oblivious to the existence of the keepers of the cosmological secrets that underlie the story, he’s aware of what makes people tick even as he dismisses their beliefs as nonsense. The reader’s curiosity about Ray mirrors his own: it’s a story of discovery, where the unknown is Ray himself.

The plot and the setting feed each other. The journey to an abandoned cliff-face Sinagua city feels a delicious beginning to Ray’s curious quest, while showcasing both the weirdness of the real West and commenting on the finitude of mortal endeavors. Dead cliff-face communities aren’t the only scenery with which Revis paints a Western-feeling Weird West. Ray’s desire for ‘answers’ over money – or even the rush of winning at gambling – imbues him with a quality perfectly suited to a Western tale’s mysterious stranger. The characters’ suspicions of each other raise the stakes of every encounter. Mechanical spiders and indestructible monofilament webs make great Weird West tech, and interwoven elements of Hopi cosmology give the story not only Ray’s ‘answers’ but unexpectedly depict a new frontier for exploration. “The Man With No Heart” proves easy to love.

Alastair Reynolds’ “Wrecking Party” is a town marshal’s account of Able McCredy’s doomed rampage against machines. “Wrecking Party” has a back-story that initially evokes tales like Steven King’s Christine or his short story “Trucks,” set in the age of steam. When the exploding shrapnel of trains’ obliterated boilers inspires a movement to ban Reconstruction-era destruction derbies orchestrated on purpose-built train tracks, something starts wiping out those who’d ban the contests. McCreedy’s Watergate-style investigation (“I followed the money”) leads him to a fellow investigator, a gear-driven woman whose extradimensionally large cranial cavity and superpowers would present a terrifying nineteenth century villain. But Miss Steel is an alien cop pursuing the same villains as he. Artificially intelligent machines with high-energy superpowers support crooked clockworks’ bid to turn Earth into an interstellar Wild West, a lawless place in which to profit on the machine-equivalent of bear baiting and dog fighting.

In “Wrecking Party” Reynolds employs a narrative style that places most of the story’s action off-screen, relayed by those speaking to the narrator. Although this places much of the action at a distance, and prevents a fast-paced in-the-action feel, the technique draws attention to the story’s horror by forcing readers to view events through the lens of surprised and helpless observers. As a bonus for a Weird West tale, it does this without making actors seem to dwell more on their feelings than suits Westerns’ male protagonists. But are they really protagonists? The primary arc of the male characters is horror: they fail in their every objective, each falling victim to the plot under investigation by the clockwork (police-)woman. Earth’s fate appears sealed, even as it gets a reprieve from its immediate threat.

To the extent there’s a protagonist, it’s the story’s only woman. She provides the only relief from predation by alien criminals. But, for how long? When will the Earth succumb to the inevitable rise of the machines? The fact that the story’s agency is borne mainly by Miss Steel – an artificially intelligent machine from another world – seems a poor portent for humans’ control of their destiny. Inevitable doom doesn’t prevent Reynolds from offering a ray of sunshine, though. The story’s last sentences suggest that – doomed or not – we keep our humanity so long as we retain the power to be decent to one another. It’s a good note on which to end a lawman’s tale.

“Hell From The East” by Hugh Howey opens with an ex-Confederate’s explanation how he ends up out West in the Army he’d shot at under Grant. Until an officer who “took the sickness” slaughters four soldiers, nothing unnatural seems afoot. Knowing this is the Weird West, anticipation builds for real weirdness to reveal itself while colorful characters circle the problem.

However, these characters and their color form a backdrop rather than participating in conflict. The action arc involves a theme of warriors changing sides, and the story presents a recurring image of being blinded by the sun. The narrator describes a native tactic of attack from the east near sunrise when onlookers will be blinded, and compares this to Europeans’ arrival from the east: settlers’ advance inspires the title. The narrator learns about a native ritual that requires staring at the sun to go blind and have visions. When he mimics it, he has visions and awakens blinded amidst his slaughtered soldiers. The story concludes with the ex-Confederate soldier in the Union army avoiding famous battles in the same stockade in which he’d earlier guarded the officer jailed over the first four soldiers so killed. Little feels changed, and the narrator doesn’t feel like he’s exercised much agency in effecting what change actually occurs.

Howey’s world contains supernatural forces apparently happy to employ enemy soldiers as hosts. It’s unsettling to observe a soldier pulled by an enemy’s ritual into communion with forces that control his body and – at least temporarily – steal his sight. That much is a clear success. But the narrator’s transformation isn’t driven by a hard choice the reader is expected to understand, it is conjured by powers beyond the ken of man. The ritual that summons a divinity to overtake the narrator isn’t a hard-won secret gone awry, but a formula handed over by chatty fellow soldier without cost or conflict. There’s little sense of plot arc: the main change is the identity of the soldier in jail. On the other hand, “Hell From the East” does effectively construct an unsettling feeling grounded in overhanging peril and the obliviousness of immigrants to the dangers of native powers. The idea that comrades in arms are readily subverted into enemies might seem more malign if the narrator’s own change in uniform had been presented with less nonchalance. Though the tale concentrates on natives’ gods’ power to control men, the conclusion proves them inadequate to turn the tide against invaders overtaking natives’ land.

Readers may wish to note that the story is not set in Howey’s post-apocalyptic world of WOOL, as indicated in error in an “about the author” note at the end of the pre-press copy of Dead Man’s Hand received for review.

Set in the same universe as his “Card Sharp,” Rajan Khanna’s “Second Hand” presents a Weird West mix of magic and gambling. Hotheaded youthfulness collides with sober reflection in a frustrated quest involving characters whose deeply broken families influence their behavior despite their relatives’ deaths. Saddled with a debt incurred getting help settling an old score, Khanna’s protagonist wants to pursue a grand noble purpose once he gets square, but there’s this last thing he’s got to do first…. His plan to find a Yoda for his ward (and himself) explodes when the would-be mentor is murdered and the story transforms from quest to flight to supernatural CSI to … well … “Second Hand.” Like its predecessor “Card Sharp,” “Second Hand” climaxes in a sorcerous duel – this time, with a wizard scheming to steal magic (and, incidentally, lives). Traditional Western themes of suspicion, greed and betrayal grow throughout the story, fuel the climax, and infuse the resolution.

There’s little doubt another story has been set up, but readers need not fear: “Second Hand” delivers a complete plot arc and a satisfying resolution even as it raises questions about the state of the characters’ relationship and the present new background for future conflicts. Unfinished overhanging ideas that leave the imagination running are what a short story is for, isn’t it? Knowledge of “Card Sharp” isn’t essential to enjoyment of “Second Hand” but is helpful to grasping both the characters’ backstory and the magical system’s operation. The full text of “Card Sharp” is available online at John Joseph Adams’ web site, and readers are encouraged to start there both to better appreciate “Second Hand” and to enjoy enough Weird West to learn why one wants to read Dead Man’s Hand.

Fans of Orson Scott Card’s The Tales of Alvin Maker will enjoy “Alvin and the Apple Tree” – the first addition to be published in over a decade. To better anticipate and follow the story, it’s helpful to understand the magic system of Alvin Maker’s world, which this story doesn’t explain, but from which the story problem grows. Most magic is invoked through the use of a “knack” – a specific ability such as starting fires, or growing plants, the subject matter and limitations of which may vary wildly between individuals. Knacks are common, and many aren’t particularly powerful. In “Alvin and the Apple Tree” the reader gets to spend time wondering how much of a small town’s conduct is a product of its peculiar religious faith, and how much is a result of someone’s knack gone horribly awry.

Readers familiar with Alvin Maker will be familiar with the stories’ religious themes and the questions they raise about Christianity and the meaning of piety. Earlier works in the series don’t exactly sell Christianity; they are populated with transparent hypocrites, fools convinced God wants them to behave badly, and churches that teach things abhorrent to any god in which a reader might find comfort. (Whether or not Card heard Twain’s advice that good fiction be built on two parts fact to each part fiction, there’s a case to be made he’s crafted an alternate history that embodies the principle.) Religiosity motivates Card’s characters, but need not motivate his readers. Readers need not accept or believe any religious tenets for any part of the story to work. Those especially sensitive to religious discussion should be aware that “Alvin and the Apple Tree” promptly drops readers into an inquiry about the relationship between guilty feelings and guiltiness, sin and blame, and unspoken judgments and real injuries to others. Characters assume the truth of Genesis’ account of the Garden of Eden, and they discuss religious beliefs as facts. Readers unable to enjoy a story with such elements are best aware in advance.

“Alvin and the Apple Tree” is not, however, about a religion – or even religion generally. Its idea is deeper, and universal. It’s about the difference between conviction and knowledge, the nature of hope, and the poison of accepting despair. On the one hand, the tale offers a sort of just-so story about why America is full of hope and despair; on the other, it presents a dark parable about people’s delight to accept things that destroy their lives. But Card’s story also contains humor: Alvin describes a town as “too small to be wickedest. You don’t even have all the equipment.” The thoughtfulness and humanity that made Alvin’s world a joy in the ’80s remains on full display.

Elizabeth Bear’s “Madam Damnable’s Sewing Circle” is told in a wonderful dialect through a first-person narrator who works as a “seamstress” at the Hôtel Mon Cherie. Bear sets this short in a steampunk Seattle unsafe to walk unescorted, whose sheriff protects his revenue above the rule of law. The major theme is freedom. Madam Damnable operates a successful enterprise staffed by willing workers: she resists girl-owning pimps while proclaiming her town a “free city” where “no letter of indenture signed overseas is going to hold water.” And she’s prepared to look after her own: she’s got one of “three or four” steam-powered surgery machines in town, and a clockwork respirator in her ICU sickroom. Though her workers prostitute their bodies, they readily distinguish between themselves and the low-rent establishments’ sex trafficking victims down by the docks. In Madam Damnable’s establishment, it’s clear who claims the power – and it’s not rough Johns.

But power proves relative. Maybe the dockside cribhouses’ slatterns have it worse, but Bear’s narrator turns out to be a teenager. A famed enemy of slavers turns out to be too young to have started fighting oppression outside her own childhood. Madam Damnable’s bordello isn’t some sex-working utopia, it’s a storm-blasted island in a sea churned to hell. Villains with mind control tech threaten even the liberty her workers manage to retain. The mind-control tech invites one to view the tale as a parable about the meaning of liberty: the worst constraints come from within, no? Race-driven social status, as accepted by an abused young Indian prostitute, emphasizes this: she limits herself by her convictions. The story seems to tell us that we’re as free as we’ll allow ourselves to feel.

Bear’s story is short – perhaps two scenes – but it’s rich with detail from a dark Weird West much better visited than moved to. The narrator’s decision that resolves the tale fits. Bear leaves us on an upbeat decision of self-determination. The story seems to have a moral that goes further: one can’t resist alone the forces that seek to constrain free will, but one need not; liberty – or what’s left of it – has champions in the unlikeliest places, and assistance is available to those who’ll accept it. To pull such an upbeat result from so dark a place is a joy to see. The fact the historical Madam Damnable died years before the date this story opens creates optimism that Bear has firm, specific ideas how her Seattle differs from the one in history books, and a plan to share these with readers. Those who enjoy Bear’s Weird West can visit it again by picking up Karen Memory – named after this story’s narrator – which Tor plans releasing in 2015. I look forward to Bear’s novel, but we can read “Madam Damnable’s Sewing Circle” today.

Tad Williams sets “Strong Medicine” in Medicine Dance, an Arizona town that doesn’t welcome strangers. But the narrator isn’t exactly a stranger, and he times his arrival for big things. Williams generates anticipation by revealing without explaining the narrator’s unnatural nature, that his visit is timed for a purpose, and that at least some locals recognize his face. When we learn his name is Custos, we’re invited to wonder what he’s been guarding and for how long. In a classic science-fiction tradition dating at least to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the horror of Medicine Dance flows from a well-meaning scientist’s efforts gone awry. The scientist – now long dead – was drawn to the place by local legends and (ha ha) unexpected artifacts we’re surely expected to conclude result from the scientist’s own manipulation of time. After the scientist’s error, Medicine Dance periodically unmoors from time and becomes subject to the ravages of bygone eras’ hazards, like dire wolves or dinosaurs. The day depicted in “Strong Medicine” provides readers an installment of Cowboys vs. Dinosaurs.

A Jurassic Park joke appears when a helpless victim stands paralyzed in horror before what by description is a T-Rex: the narrator congratulates her on having the good sense to freeze. Michael Crichton’s The Lost World depicts an academic who, having “read the wrong papers,” tried this technique in the conviction a T-Rex’ eyesight is froglike and sees only motion. Crichton’s T-Rex has birdlike vision, however, and easily spots and eats the unmoving academic. By contrast, “Strong Medicine” makes the tactic good for an hour’s survival – at least for a named blonde female. But it’s an off-screen victim’s hour: on-screen, the action doesn’t stop after the first dinosaur attack. Oblivious locals try rafting a monster-infested sea, velociraptors fall on cattle like children upon cupcakes, triceratops unintentionally level townsfolk’s structures, and a young blonde is cornered on her front porch by a Tyrannosaur. Her poor dog is repeatedly imperiled, drawing the male leads into action.

“Strong Medicine” is an action romp. The saved-by-the-bell end to the dinosaur attack provides a nicely dark Man-is-not-master-of-all lesson, but brings little feeling of resolution. On the bright side, the answer to Custos’ identity proves much better than anticipated. Anyone starving for a Weird West rampage of dinosaurs against frightened townsfolk’s archaic firearms will be pleased to know there’s “Strong Medicine” for that condition.

Jonathan Maberry opens “Red Dreams” with a falling star observed by McCall, a soul-weary forty-something disgusted with his work guarding West-bound wagons by gunning down natives. The story starts with successive waves of back-story detailing McCall’s recent battle, his work under an Army commander whose conduct against natives proved so outrageous as to provoke discipline (no small feat then), and his recollections of men desperate to die. It’s a dark background fitting an unhappy man with a nasty past. Anticipation builds quickly over the falling star’s true nature – surely in a Weird West tale, it will prove unnatural – but multiple flashbacks work against a feeling of momentum behind the story’s progress.

When dead men begin appearing in the tale, McCall is as curious as the reader, though more panicked – he empties his revolver into the first, without effect. But the dead seem to know as little about how they entered the scene. A horror-story feel builds as violently-dispatched corpses walk into the tale and depart, invulnerable to weapons and acting on motivations they won’t share. The unsettling end’s lack of answers sets “Red Dreams” squarely in the realm of the Weird. But so little is answered that it feels unsatisfying. Why did the dead rise? Where are they going? What’s the falling star? The resolution answers no questions about the afterlife, even for the murdered, but McCall’s character arc closes in a place that suits his path. Fans of Weird fiction, who revel in unsettling endings and don’t require neat resolutions, will feel right at home at McCall’s campfire.

“Bamboozled” by Kelly Armstrong opens with thieves preparing a con outside a small town in the Weird West. One of the thugs accompanying the band’s female “bait” is unnatural – fae, or were, perhaps. Anticipation builds both for the scam’s development and the nature of the supernatural perils involved. The Western setting is contrasted culturally with society elsewhere in the world, and the tale delivers a convincing feeling of location. Armstrong’s tale provides not only the double-cross expected in any con, but a host of real surprises: the real target of the scam, the frequency of nonhuman weirdos in the West, the characters’ powers, the extent of the betrayal, the protagonists’ real line of work, the characters’ relationships. The first scene promises a strong female lead, and Armstrong delivers. There’s no fun in spoiling a heist’s twists, of course. Armstrong’s tale has a lively pace, entertains with quick reversals, and provides just desserts perfectly suited to the Weird West.

“Sundown” by Tobias S. Buckell opens with a nervous Marshal riding into Duffy, Colorado after a fugitive he fears less than the town. When locals blame cattle mutilation on “Indians” at the close of the first scene, we wonder what’s really troubling Duffy. And when we discover Marshal Kennard is “negro,” there’s no feel of Blazing Saddles: Duffy may be dangerous, but it isn’t funny. Whether from racists or inhuman killers, men of the law soon find themselves outnumbered by armed adversaries. In either case, both stand at risk. “Sundown” depicts two African American protagonists in law enforcement. Standing up to the “Black Dude Dies First” trope (remember Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan? Chekov made it, is all I’m sayin’), “Sundown” has Duffy’s white Sheriff bite it when the horde hits; he goes down defending his jail, and Kennard. Good on you, mate.

The pace of the story takes a sharp turn when Marshal Frederick Douglass (yes, that Frederick Douglass) appears to dispense heavy exposition about the advances in technology and racial advancement. Thankfully, they’re quickly subjected to dynamite bombardment from an enemy airship and the real emergency is disclosed: Earth is under attack by aliens whose ship America unwittingly acquired when it paid Russia for Alaska, where the aliens’ craft crashed. Driving a captured United States airship – from description, a coal-fired steam-dirigible, which you just can’t not enjoy – the insect-aliens descend on the mines near Duffy. Can our heroes hold out until Douglass’ carrier pigeon summons the rockets of the U.S. cavalry?

Buckell’s story draws unexpected strength from the nonstop addition of gratuitous unlikelihoods: like Münchhausen’s outrageous lies or a Texas tall tale, “Sundown” keeps going, fearlessly indifferent to its incredibility. And in the tradition of the best tall tales, our hero lands where only Jupiter’s chariot can save him. Frederick Douglass with a cart-drawn Gatling gun saves Kennard when he’s cornered by an alien horde that outnumbers his bullets, for starts. But why spoil things? Roll with it. It’s a tall tale. You’ll enjoy every minute you shake your head.

Jeffrey Ford’s horror story “La Madre Del Oro” (“the mother of gold”) promisingly opens with an ambitious California-bound protagonist hungry and penniless in New Mexico. Desperation for cash is a traditional Western motive, and what’s more Western than joining a posse to kill some lowdown dog with a price on his head? The only question is what kind of supernatural phenomenon explains the accused’s cannibalism. It’s easy to sense the weird coming, but at the outset it’s the Western feel that dominates. Well into the posse’s hunt, the story takes on the feel of a ghost-story. Then gold fever turns survivors careless: leaving sight of the main character to stroll into the depths of an abandoned mine in the middle of a ghost story is never the conservative move. Soon our hero isn’t worried who’ll collect the bonus for killing the fugitive, he’s worried about escaping with his skin. The resolution perfectly suits a ghost story’s horror vibe, leaving readers to enjoy a strong sense of “I shoulda listened to Ma” and “I coulda just stayed home.” But then, what fun is that? If you don’t risk all for California gold, where will you get those great stories about the demons who’ve hungered since they ran out of conquistadores, but linger still?

Ken Liu grounds “What I Assume You Shall Assume” in the history of minority oppression in China and in the United States. The story’s immediate villains are thugs emboldened by the Geary Act, a real-life statute from which Liu quotes to illustrate anti-Asian prejudice elevated into federal law. Liu depicts desperate injustice in the stark difference between long-cherished rights like liberty and property, and the realities faced by Asians in a land of greedy bullies backed with federal statutes in which law made no pretense at serving justice. Focus switches between an American loner fleeing West, and an Asian community’s leader who immigrated to provide financial support in China for developing there the values Americans purport to cherish. Liu’s villain is a crooked Sheriff writ large: instead of one grasping lawman directing illiterate killers to enrich one man, Liu depicts the government of the United States formally authorizing the worst oppressions against peaceful immigrants, for the benefit of anyone caring to enrich themselves with property from which they drive Asians.

Liu establishes an Asian sorcery based on written words, with which his female lead combats illiterate oppressors seeking to squat an Asian-held prospecting claim. Liu connects power to learning in a tale that places on those who want justice the duty to bring it into being. The stark difference between law and justice fuels the victim’s resistance, as the printed text of opaque legalese becomes, in her hands, a shield against pursuers. When things look hopeless in a Weird West that amplifies the power of ideas, the power to change one’s self takes on new dimensions.

Liu paints a large portrait on a small card. Huge ideas intertwine the story action, as do themes that pervade life and society. The explanation why the Tienching Rebellion failed in China – and how war to maintain the Union led to a new wave of oppressions in the U.S – seems to invite the darkest tale. The theme that words are only as good as we make them feels like it should doom a land of rights secured by laws crafted from words, as faith in grand ideals wanes over time in favor of self-interest, prejudice, distraction, or sloth. It’s a perfect setup for a tale of despair mirroring some real history of the fight for justice and liberty in China and the United States. But Liu’s story draws on a basic Western convention in positing that there is a hero, even in unlikely places, and there’s little use resisting a good man moved to action. Liu himself employs sorcery based on written words, showing the power of one believer against the madness. It turns out words are magic, after all. Read Liu’s, and join the revolution.

Laura Anne Gilman’s “The Devil’s Jack” opens on Jack’s exhausted flight on a horse about to give out. The desperate fugitive is, of course, a recurring Western character. In Gilman’s Weird West, Jack flees not mortal law but a debt owed the Devil. Of course, in bargains with the Devil it’s tradition that someone tries to cheat…. The themes of freedom and redemption stand balanced against consequence and obligation. Those who’ve dealt with the devil bring trouble to themselves and those about them. Jack may be all but spent, but he’s not too tired to fight his dirty job. “The Devil’s Jack” shows a sympathetic loner doing what good he can despite his awful lot. The resolution shows even a damned man retains power over the good or ill he does afterward – and in a soul so exhausted, that may be the best he can hope for.

Walter Jon Williams’ “The Golden Age” looses a costumed superhero on the lawless expanse of the Gold Rush. Rather than take for his protagonist The Condor – a straight-laced law-and-order defender of capital-J Justice – Williams follows a sailor-turned-prospector who comes to be known as The Commodore as he tries to steal back what was stolen from him, despite the new law and order imposed by do-gooders. Soon, The Condor inadvertently creates the first costumed super-villain in the Weird West. Uh, oops.

“The Golden Age” parodies superhero tales – the no-firearms combat, the silly gimmick attacks, characters leaving adversaries alive to create trouble later, and – in apparent homage to The Incredibles – using an enemy’s own cape to defeat him. The Commodore proves fully aware of the madness that drives him to embellish his outrageous costume just as it fuels his growing rivalry with The Condor. The unwritten code governing costumed crime-fighters and their top-tier quarry is on full display in “The Golden Age” and if you’re at all rusty on the rules, it’s a great place to start. Don’t drink milk while you do, unless you like blowing it out your nose.

The Weird West at first feels cheerful with Aero Lad racing the skies on his mechanical dragonfly and steamboat pirates plying the waters between working claims and Sacramento. The slowly-improving Sacramento City Jail provides longer minion-recruiting opportunities between escapes, so it’s no threat to business. The Commodore dishes the inside scoop how superhero match-ups develop, and why every episode has a different combination of villains. Nowhere is so much superhero psychology on display in so little space. Not to be missed.

Alas, paradise cannot last. The lark that was the “Golden Age” shifts gears when a real villain appears, dispensing slavery and murder. Takes the fun right out of tights-clad escapades. But then the real threat – law and order backed by a functional government – leaves costumed arch-enemies with a ticking clock on the score they long to see settled before the Golden Age truly dies. Williams’ supervillain and his costumed nemesis collide in a resolution filled with longing for gold, freedom, justice, someplace to party … and a good fight. This story could have ended satisfactorily in so many places, it feels a pure gift Williams held out for the finale he ultimately delivers. Read it.

“Neversleeps” by Fred Van Lente depicts the Pinkertons’ unblinking eye in business in the Weird West. Instead of being set in an alternate past, Lente’s tale occurs after an “awakening” that unleashed supernatural forces upon a world presumably otherwise like that we know from history books. Followers of Tesla and Edison eye each other with suspicion while duking it out with magic wielding Pinkertons on a train flying on ley lines. Political maneuvers, traps, double-crosses, a heist on a moving train – the crazy builds with the climax. “Neversleeps” may be a short ride, but it’s quite a rush.

Christie Yant’s “Dead Man’s Hand” provides alternate accounts, styled as if from newspapers, of the confrontation that in historic Deadwood killed James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. The accounts do not combine to a coherent narrative. Instead, they invite the reader to view a past event through remote and conflicting sources of dubious reliability. The effect is to invite inquiry into the extent of truth in each (and whether lack stems from deceit or misinformation), and the potential that an account comes from an alternate history where the world and its characters really were different. At first blush, one wonders how the collection is a story. But it’s four little stories, each inconsistent with the others. Viewed as a whole, the assemblage questions like who killed who, really; and how, and why, and when. This format may not be for everyone, as it doesn’t give the feel of a single plot arc; for the willing, it proves interesting. Re-read the opening paragraphs when you’re done. When you wonder not only which story is true (or was) but for how long it will remain true, you’ve found Yant’s ticket to the land of the Weird.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

# # #

An Anthology of the Weird West

edited by John Joseph Adams

(Titan Books, May 13, 2014)

“The Read-Headed Dead” by Joe R. Lansdale

“The Old Slow Man and his Gold Gun from Space” by Ben H. Winters

“Hellfire on the High Frontier” by David Farland

“The Hell-Bound Stagecoach” by Mike Resnick

“Stingers and Strangers” by Seanan McGuire

“Bookkeeper, Narrator, Gunslinger” by Charles Yu

“Holy Jingle” by Alan Dean Foster

“The Man With No Heart” by Beth Revis

“Wrecking Party” by Alastair Reynolds

“Hell from the East” by Hugh Howey

“Second Hand” by Rajan Khanna

“Alvin and the Apple Tree” by Orson Scott Card

“Madam Damnable’s Sewing Circle” by Elizabeth Bear

“Strong Medicine” by Tad Williams

“Red Dreams” by Jonathan Maberry

“Bamboozled” by Kelly Armstrong

“Sundown” by Tobias S. Bucknell

“La Madre del Oro” by Jeffrey Ford

“What I Assume You Shall Assume” by Ken Liu

“The Devil’s Jack” by Laura Anne Gilman

“The Golden Age” by Walter Jon Williams

“Neversleeps” by Fred Van Lente

“Dead Man’s Hand” by Christie Yant

Reviewed by Ryan Holmes

There is something fascinating about the frontier, something romantic, luring. Perhaps it’s a desire to be free, unhindered by the law or the strictures of civilization. Maybe we see the strength and courage it takes to thrive on our own, the grittiness, the callouses; we wish to try our luck, to prove to ourselves we’re just as hard. Whatever our draw to the wild, the open, the deadly, we’re never quite ready for what we find.

This anthology succeeds in delivering all of that and more, and we’re readily surprised by the stories we encounter within. Among them, there are many gold nuggets, and we read them with the same fever prying our eyes from one word to the next, drawing our fingers to sift through another page. We find a couple that excite us at first. They gleam with the same yellow glint as the rest but in the end turn out tarnished, poor copies of the others. Yet all of them are worth digging out.

In his introduction, John Joseph Adams begins by acquainting us with the term ‘dead man’s hand,’ and we soon realize there’s far more to the legend than we might think. Adams takes care to describe the differences and similarities between weird westerns and steampunk. The unfamiliar reader gains a keen and clear insight for what weird western is all about. Adams also pays tribute to the genre’s history and credits its defining work, “Dead in the West” by Joe R. Lansdale. The mention of Lansdale’s work is not casual. It serves as a transition. The first story is written by the genre’s foremost expert. The introduction is as entertaining and intelligent as it is effective and ends with a clever and humorous turn of words.

Joe R. Lansdale‘s opening story “The Red-Headed Dead” is set in east Texas in 1880. It finds the gun-slinging Reverend Jebediah Mercer chased by a tornado. He’s a man cursed by God to defeat Hell’s minions as part of His twisted game of sport. The Reverend flees through a forest along a pine needle path that takes him to an overgrown graveyard with an iron rod leaning out of the ground over one of the graves and then to an abandoned cabin against a hill. The Reverend and his horse shelter inside. The tornado hurls earth, trees, and the iron rod at the cabin. What the iron rod pinned down follows. The Reverend must climb his way out and return what the tornado unleashed to its final resting place.

Lansdale’s Reverend is an unwilling champion of God with as much internal conflict about how he views his maker as bare knuckle brawls with Hell’s agents of evil. He is easy to sympathize with because the reader can feel how fed up he is with being led around on a divine leash and toyed with at His whim. Then just as the reader understands the Reverend’s internal battle, Lansdale pulls away and throws him into a fight for his life. The fighting is immediate and gritty. Lansdale doesn’t pause the scene to tell how the Reverend is feeling as this nightmare from beyond the grave tries to rip his throat out. I found that refreshing. The Reverend is that much more believable.

“The Red-Headed Dead” isn’t without faults. The cabin for one has no other purpose than to stage the encounter with the dead. It’s empty and convenient. Had Lansdale chosen to occupy the cabin with a frontier woman then there would have been much more at stake and the cabin would have history, depth. One hang-up stems from the Reverend not coming from or going to anywhere prior to the story’s events or after. He’s simply on top of a hill when a tornado comes calling. Had Lansdale included where the Reverend was riding from and where he was aiming for then the reader would want to know more. Lansdale does give a location and time period: East Texas, 1880. Readers familiar with the Reverend may be able to place this event in the overall timeline. Lastly, Lansdale creates a powerful foe, but the Reverend walks away only slightly worse for wear, more of a John Wayne than a Clint Eastwood. These are minor issues, and Lansdale tells the tale well enough that they are only evident afterward.

Ben H. Winters‘s “The Old Slow Man And His Cold Gun From Space” takes place in Sacramento, California in 1851. Two unsuccessful prospectors, Caleb and Crane, couldn’t be more different. Caleb is big and muscular. Crane is skinny and wears spectacles. But both are stubborn and determined to strike it big on the Sacramento riverbanks. One night, they are awakened by a crazy old man with an antique flintlock pistol and a wild proposition. He claims he’s from Neptune and the pistol can find gold, but Earth’s atmosphere leaves him tired. He needs Caleb and Crane to dig the gold for him and offers to split it fairly. The trouble is trustworthy partners are hard to come by when gold fever hits. Winters gives the story an authentic voice true to the period and two very believable prospectors. The reason the Neptunian needs the gold is as imaginative as it is original, but the biggest surprise is the unexpected twist at the end.

“Hellfire on the High Frontier” by Dave Farland is set in Wyoming Territory in 1876. Morgan Gray is a Texas Ranger hunting an Arapaho skinwalker. He’s a Texas Ranger in Wyoming because ‘justice shouldn’t be bound by borders.’ When The Stranger appears (something neither angel or demon but altogether different) at Morgan’s campfire we learn that Morgan owes a debt and agrees to track down Hellfire, a clockwork gambler who has a recurring pattern of killing a random person every four months to the minute. Morgan doesn’t make it to Fort Laramie in time to save a showgirl, but the town raises enough money to put Morgan on a dirigible so he can follow Hellfire to a city in the clouds known as the High Frontier. Farland’s story imagines a west where God is dead, killed by mankind’s faith in his own creations, His angels reduced to feral, fairy-like beings that entertain the rich in cages hanging from the ceiling. Or maybe the fight between nature and machine is still raging, and beings like The Stranger need men like Morgan Gray to tip the scales.

Mike Resnick‘s “The Hell-Bound Stage Coach” picks up in the Arizona Territory in 1885. Three men and a lady discover they’re dead and headed to hell. They get the driver to stop and decide they’re not ready yet. They want to build a rest stop where the lady can sell her delicious baked goods. This story has a good beginning as Resnick unfolds the mystery of the stage coach’s passengers. We gain an intimate knowledge of all four of them. We even sympathize with them during their journey to the ‘end of the line,’ despite all but the lady being ruthless gunslingers. Unfortunately, the ending is difficult to believe and ruins what is otherwise an interesting story.

“Stingers and Strangers” by Seanan McGuire begins on the Southern Pacific Railway heading westbound through Nevada in 1931. The story introduces a cryptologist, Johnathan Healy, and his female circus performer turned apprentice, Frances Brown, as they hunt giant wasps, lodge at a dragon princess’s bed and breakfast, and fight off the mind-controlling predator forcing the wasps to refuge in town. Before we get to really know Healy and Brown, we’ve already fallen in love with them. The quick banter and roughneck personality of Brown acts as counterpoint to Healy’s educated, formal, and proper demeanor. The chemistry between them sizzles and would have us turning pages even had McGuire not graced us with a well-structured plot rife with tension and mystery. The worse part about this story is that it ends abruptly, as if part of a larger story or series (McGuire even states the identity of the mystery, mind-controlling woman ‘needs to be resolved’). McGuire put a lot of thought and effort into this story and leaves us screaming to read more.

Charles Yu uses an interesting style in “Bookkeeper, Narrator, Gunslinger.” It is set in Lost Springs, Wyoming in 1890 and starts out a narrated story about the three fastest draws in town. When the slower two standoff, the narrator becomes part of the story and unwittingly gains a reputation as one of the fastest guns around. Weird applies to both the plot in this western and the author’s style. From a modern speaking gunslinger poking fun at the period-correct diction of another to the intentional narrative intrusion, this story makes an exception to the rules. If you’re not unhorsed by the narrator’s intrusion then you’ll find plenty of entertainment in this story.

“Holy Jingle” by Alan Dean Foster is a Mad Amos Malone tale set in Nevada Territory in 1863. The mountain man rides into Carson City on his way to San Francisco and is enlisted to recover a stage coach driver’s trusted hand from the clutches of a Chinese courtesan in the local bordello. Malone bursts in and wrangles the man from the chinawoman, who tuns out to be possessed by a Huli jing. Amos dispatches the apparition and offers to take the woman with him to San Francisco. It ends all of a sudden with little in the way to suggest Malone was in any real danger. Foster uses a laborious and wordy style of exposition with a similar dialogue, what little of it there is in the story, to portray an over the top character that makes the whole thing a bit like swallowing cheap whiskey.

Beth Revis sets “The Man With No Heart” in Arizona Territory in 1882. Ray Malcolm is a man searching for answers. There’s something strange about him, underneath the skin, which drives him to follow a man with a clockwork spider to the place he acquired it. It turns out the man got the spider off an Indian after he’d shot him in an ancient cliffside dwelling. The man tells Ray the Indian was from Big Canyon. Ray heads there and in the night finds dozens of clockwork spiders walking over the edge into the canyon. Then he meets the Indian’s brother, Cheveyo, who tells Ray they have been guarding the canyon, the birthplace of the world. Earth is but one of four. Ray doesn’t believe him and follows the spiders into the canyon in search of answers, despite Cheveyo’s warnings. The spiders’ trail leads Ray to a cave and to answers, but not the ones he was expecting. The ending here was a little disappointing. Ray seems to get everything and sacrifices nothing.

“Wrecking Party” by Alastair Reynolds takes place in Arizona Territory in 1896 and begins in the middle of a rainy night with a mad man wrecking a horseless carriage outside of Quail’s saloon. The town Marshal, who goes by Bill, apprehends the mad man. While interrogating the mad man for wrecking the machine, Bill recognizes the man as Abel McCreedy, who served with him in Hampton’s Legion. Abel tells Bill a strange tale that began with the wrecking parties where rich folks would gather to see two trains collide. Spectators died and the Utah Congressman who tried to stop it wound up dead. The congressman’s brother did some digging and disappeared, so his wife hired Abel to investigate. Abel followed the money and met someone else investigating the wrecks, Miss Dolores C. Steel, a machine intelligence here to stop others like her from having sport with lesser machines. Steel warns Abel to stay away, but he doesn’t listen and now they’re after him. Reynolds creates a universe where machines always triumph over organics, and we can’t help but wonder if our own future will follow suit.

Hugh Howey‘s “Hell from the East” occurs in Colorado Territory in 1868. It’s about a former Confederate soldier who enlists in the Union to fight natives. The story is about the Ghost Dance which later became known as the Messiah Craze. While he’s stationed at Fort Morgan, a lieutenant takes to the sickness and kills his own men. The soldier (Howey never reveals his name) heads out with a Private Collins to find answers as to why the trail scout went crazy. They find his camp up in the hills, and by the looks of it, Private Collins assumes the lieutenant went native. Collins identifies a sun hut in the camp and explains the Arapaho dance in it as they gaze up at the sun. They report what they found, and our soldier heads back out with John McCall to investigate a cattle disappearance. When the two split up, our soldier starts staring at the sun, trying to understand why the natives would do it. First, he does it out of curiosity, then out of stubbornness not to be out done by savages. He catches the sickness, hears whispers in his mind, and sees a vision before passing out. He wakes back at the fort unable to see and fearing he may have hurt people like the whispers had called him to do. The story uses the expansion of conquerers from the east, from across the ocean, to suggest another conqueror is coming from across the expanse of space. We, like the Red man, are naive to think that no one will ever cross that ocean.

“Second Hand” by Rajan Khanna is set in Wyoming Territory in 1874. Quentin Ketterly is a Card Sharp. His Cards can perform magical feats, but once he burns a Card from the Deck, it’s gone, and there’s only the one Deck per Sharp. He’s saddled by a promise to protect Hiram, his teacher’s careless son, who likes to waste his precious Cards cheating at poker. They’re tracking down a list of names the old man gave them, looking to learn more about using the Cards. The last name on the list is “Gunsmith,” who turns out to own a gun shop in town. She reluctantly agrees to teach them. Only, before the first lesson begins, they find her dead, the shop busted up, and her Deck missing. While searching upstairs for clues of where to go next, they’re interrupted by a young woman. The woman is Gunsmith’s daughter, Clarice, and another Card Sharp. They agree to help her find her mother’s killer, but the daughter has other ideas. She knows a secret about the Cards, a way to get more, and turns on them. Quentin and Hiram wind up finding out more about the Cards than they’d like to know, but they’ve got a new list of names, thanks to Clarice, and good reason to be more careful around other Card Sharps and each other. In this world of limited magical cards, we learn what greed and desperation will drive some people to do.

Orson Scott Card brings us another Alvin Maker tale in “Alvin and the Apple Tree.” Set in the State of Hio in 1820, Alvin meets John Chapman, otherwise known as Johnny Appleseed. They discuss what it means to each man to be Christian. Alvin learns of Chapman’s knack for growing apple trees from seed and continues on to Piperbury, a town Chapman claims is full of godly folks. Alvin arrives during a funeral and soon discovers the town is full of despair for unvoiced sins against their fellow townsfolk that leads them to create accidents. They’re kind to him, offer him a place to stay the night, and feed him a modest dinner, including a delicious apple pie from the orchard Chapman had planted there. When Alvin awakes, he feels just as full of despair as the rest of the town. When he realizes why, he tracks down Chapman, who admits to making a special tree in Piperbury, a failed tree. With Alvin’s help, they find a solution that will save the town from despair. Card explores human nature and our brokenness as it pertains to the Christian story of Creation. He gives us a parallel to the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, one that helps us relate to our own nature and how that nature drives us to behave.

“Madam Damnable’s Sewing Circle” by Elizabeth Bear takes place in Seattle, Washington in 1899. The story is told through the perspective of Karen Memery, a ‘seamstress’ in Madam Damnable’s Sewing Circle, which is actually a brothel. All the sewing is finished for the night when Merry Lee, a Chinese working girl from the docks who’s escaped and fights to free others, bursts in, shot in the back and towing an Eastern Indian girl named Priya. While they are patching up Merry Lee, Peter Bantle and three of his henchmen bust in. Bantle wants Priya (his property) back and Merry Lee for all the trouble she’s caused him. Karen and another ‘seamstress’ fend them off at the door with a shotgun. But Bantle has an odd device on his wrist that he turns on Karen. It twists her thoughts until she’s ready to help the man. She’s saved when Madam Damnable comes down from her room and convinces Bantle to leave. Karen goes upstairs to bring food to Priya and help with Merry Lee, who is having her bullet removed with a clockwork knife machine that hangs on the wall in their clinic. Karen learns that some women, like Priya and Merry Lee, can’t be broken. She takes up their fight and pledges Peter Bantle will pay dearly.

Bear gives Karen a charismatic narrative voice that carries the story despite never really resolving the conflict with Bantle or explaining his mind-altering device. We gain a clear understanding of the knife machine, but as just a surgical device, it is easier to believe. Then the story ends abruptly with a promise to deal with Bantle instead of actually doing it.

Tad Williams‘s “Strong Medicine” takes place in Arizona Territory in 1899 and centers on the town of Medicine Dance. Most of the townsfolk don’t remember Custos when he walks into the Carnation Hotel to visit on the day before Midsummer. Strange things, little things, happen in Medicine Dance on Midsummer day, but every thirty-nine years Medicine Dance leaps out of time to land for a day in another time period. Custos is back to protect the town from the dangers jumping through time can bring. He has a particular attachment to one family, the descendants of Professor Noah Lyman. Lyman’s machine mistakenly cursed the town long ago during a failed experiment, and he created Custos to be its champion. Williams does a good job of hinting at what Custos is and what he knows without revealing it until the end. The story shows us the great lengths a person will take to right a wrong and protect the people who are important to us.

“Red Dreams” by Jonathan Maberry sets his story in the Wyoming Territory in 1875. We find McCall wandering on a horse named Bob as he watches a star fall out of the sky. McCall imagines it’s an angel, one coming for him with a flaming sword. McCall is deeply troubled by a violent past. He most recently took part in a bloody encounter with Cheyenne dog soldiers led by Walking Bear. McCall is troubled that he survived when all sixteen of his men and thirty-four dog soldiers, including Walking Bear, did not. He is haunted by those events and becomes increasingly disturbed, but not nearly as much as when Walking Bear sits down at his campfire, bullet-riddled chest and all. Or when other men from that gunfight, his men and dog soldiers alike, all dead men, walk past them into the night. White men and dog soldiers walk separately and sometimes together, whispering to themselves and keeping their distance from McCall’s campfire, every one of them a victim of murder. McCall tries to make sense of it, asks Walking Bear if he’s supposed to live the rest of his life atoning. Eventually, he discovers what he must do, though he resists it to the last. Mayberry creates a powerful message with this story that teaches us how little our differences matter in death. He illustrates this point the strongest when he depicts the White men walking together with the dog soldiers, bitter enemies in life, allies in death.

Kelley Armstrong‘s “Bamboozled” is set in Dakota Territory in 1877. Lily is an actress performing in saloons when she meets rugged and mysterious Nate who defends her honor. Afterward, she leaves her acting group and joins Nate. Nothing is what it seems in this story. Nate and Lily have a crew of three other men who believe they’re conning rich people out of their valuables, but the mark, a rancher looking to remarry, is a ruse. Nate and Lily really hunt monsters, specifically a half-demon in the rancher’s employ. But Nate and Lily have also been bamboozled, their crew are not all what they seem, and the tables are turned on them. This would have been a better, self-contained story if it had ended with the ironic demise of the talented actress, but Armstrong takes it to the next level, packs in another twist, and leaves us hooked and wanting more.

“Sundown” by Tobias S. Buckell takes place in Colorado State in 1877. Willie Kennard is a black US Marshal, one of the first, and rides into Duffy near sunset in pursuit of a murderous fugitive. A black man in Duffy after sundown could get lynched, star or no star, so Marshal Kennard is in a hurry to find the town’s sheriff. When he’s told the sheriff is investigating a cattle mutilation at a ranch outside of town, Kennard spurs his horse in that direction. The rancher, like Kennard’s fugitive, is possessed, his brain full of insect parts and a large stinger. Kennard demonstrates this to the sheriff when he blows the rancher’s head off. Despite the evidence and the danger to the town, the sheriff still locks Kennard up for the night for his own safety, but agrees to let him keep his two Colts. When the townsfolk come calling, the sheriff isn’t sure whether they’re possessed or just want to lynch the Marshal. It turns out to be the former. Kennard is conveniently rescued by Frederick Douglass, the first black Marshal, who turns a wagon-mounted Gatling gun on the jailhouse and mows down the possessed townsfolk.

The appearance of the grandfatherly Douglass has an enormous effect on the remaining story, for the worse. It is almost as if “Sundown” was written by two authors. Prior to Douglass, the story is rather well written. After Douglass, the story contains a great deal of explanation as Douglass dryly recounts how he became a Marshal, his mission to recover the government airship now pursuing them, and the alien craft that had landed in Alaska, possessed the airship’s crew, then flew it to Colorado to possess Duffy and a mine just outside of town. Kennard gets to explain how great a Marshal he is, single-handedly taking down numerous outlaws with legendary marksmanship, while the two men holed up in a cave. In the end, they take out the airship with a flare gun and dispatch all the possessed miners and townsfolk in Duffy just in time for Douglass’s cavalry to burn all the bodies for them. Douglass offers Kennard a job helping him track down any remaining infected in the countryside, but Kennard turns it down claiming he’s headed east to find a good woman and rides off into the east with the sun setting behind him. The story would have been far better if it had ended at the jailhouse with Kennard being rescued in a less convenient manner, or perhaps going down shooting like the far more believable sheriff.

Jeffrey Ford sets “La Madre Del Oro” in the New Mexico Territory in 1856. The story follows a young man named Franklin who left his family’s Pennsylvania homestead at the age of sixteen for the California gold fields. We find Franklin four years later arriving in Las Cruces penniless, starving, and well short of his destination. Desperate for a job, Franklin joins Deputy Stephen S. Gordon, a gunslinger named Fat Bob, and a Mexican tracker named Sandro on a manhunt to kill the cannibal Bastard George along the Jornada Del Muerto (the Trail of Death) for four dollars a day. Franklin is both green and naive, but the four dollars a day will take him to California, so he signs on unaware of the risks. The party catches up with Bastard George, gets hit by a sandstorm, discovers an old Conquistador gold mine, and encounters the old mine’s supernatural inhabitants. As we shake our heads at Franklin’s many questionable choices, we can’t help but root for the kid. We are so focused on Franklin that we hardly notice the misdirection Ford creates. The story serves to educate anyone considering giving up what they have for the illusion of something better and cautions them to go prepared.

“What I Assume You Shall Assume” by Ken Liu is an 1890 tale set in the Idaho Territory about Amos Turner, an old mountain man who has lost hope in humanity, and Yun, a chinawoman who’s trying to give it some through the power of words. She is a former general in the Heavenly Kingdom, a Chinese freedom group, come to Idaho Territory in search of gold to fund their cause. A recent government proclamation has made it unlawful for Chinese laborers to remain in the territory for more than ninety days. Amos finds Yun fleeing a band of men eager to help the government and steal her claim. When he agrees to help her, he discovers Yun can use the meaning of written words to perform a similar act of magic.

This story centers on the ability of words to inspire ideas and the power of those ideas to change the world. Amos lived through the Civil War and saw the government break every treaty with the native Indian. Yun’s ideals seem to Amos like a lost cause, but she convinces him it is a cause to keep fighting, no matter how many times it might fail.

Laura Anne Gilman introduces us to “The Devil’s Jack.” After losing to the devil at a card game, Jack must pay off his debt by collecting souls. In 1801, his master calls him to Briar to claim ten good men who traded their souls to protect their town when an abomination, unleashed long ago by a wizard, returns. On his way, Jack seeks refuge on a rock ridge. Rock and water are his only escape from the devil’s pull. While there, he encounters demons bound to the rock by the town’s wizard. Jack can’t bring himself to deliver these good men to the devil and negotiates a bargain of his own between the demons (a lesser evil) and the town. Jack and his internal turmoil make for an immediately likable character. His defiance of his master and pity for the damned men of Briar adds to our sympathy, and we wish for him to be successful in getting one up on the devil.

“The Golden Age” by Walter Jon Williams occurs in Alta California in the spring of 1852, the height of the gold rush. It begins by setting the scene of an ambush. The Commodore, an outlandishly dressed pirate on the Sacramento River, is waiting to plunder gold from a man wearing the costume, and taking the name of a condor. From there the Commodore tells the fantastic story of how he came to be the arch nemesis of the Condor. Strange and eccentric villains abound, each attempting to steal what the other illicitly acquired first. The Condor pursues them all, until a foreigner shows up and bombs San Francisco with fluorine gas. Gold stops coming down the river, supplies become scarce, and the villains must align with the Condor to overthrow this common foe. In the aftermath, news of government reinforcements on the way to San Francisco’s aid heralds the end of the villainous gangs’ lawless golden age. The Commodore and the Condor know they must move on, but not before one last showdown to settle the score. Williams tells an engrossing tale about the old west’s superhero from the perspective of his greatest villain.

Fred Van Lente places us on the Northwest Pacific Express heading northbound near Navajo Territory in “Neversleeps.” The story alters history with the Awakening, where the spiritual forces of the world return and replace the Age of Reason. Science is outlawed, and scientists are burned at the stake as the governing powers of the world embrace this new age with vigor. Simon Leslie is a former agent of those powers turned renegade and serves the White City (founded by Edison) in its quest to restore order and freedom. Simon is on the train to rescue the female atomist, Nicola Tesla, (descendant of the martyred Nicola Tesla) after she is turned over by Navajo to three Pinkertons. The rescue doesn’t go over as planned, and Simon, being an Edison-man, must escape capture by dragging along an ungrateful Tesla. The story is imaginative with its examples of how mystical powers might replace physical forces. The conflict between Simon and Nicola works well as this world and its events unfold. Unfortunately, this is more like a chapter in a novel than a standalone story. It begins well, raises questions, conflicts, resolves a few, and abruptly ends without a proper denouement.

“Dead Man’s Hand” by Christie Yant takes place in 1876 at Deadwood in the Dakota Territory. As the name implies, this story is about Wild Bill Hickok’s last hand of poker. It is told through the eyes of a journalist in a series of news reports. Each article is unique and brings with it a reference to the “Dead Man’s Hand.” We learn through this story (and the anthology’s introduction) that there are a number of varying accounts as to what cards were dealt to the soon-to-be-dead man. Yant plays on the myths of the famous hand and creates an alternative reality for each one and shows us just how random life, and cards, can be. The reports create powerful imagery and convey a great deal about the characters in precious few words. One can’t help but wonder what Wild Bill would think of them and the legend he unwittingly left behind.