edited by

Mike Allen

(Mythic Delirium Books, April 2016, 271 pp., tpb)

Reviewed by Nicky Magas

Life hasn’t always been as peaceful and comfortable for Benito as it is now, but in Jason Kimble’s “The Wind at His Back,” Benito has put the worst of it behind him. He’s got a steady job, a loving husband and the support of the community he serves to ground him when his mind goes to dark places. What’s done is done, or at least that’s what Benito thinks until a storm from his past blows in and threatens to undo everything and throw his world into violence and fear once more. With everything he loves at stake, Benito must face down one last twister, or else abandon everything he has worked so hard to build.

The first few paragraphs of “The Wind at His Back” create such an atmosphere of mystery and fantasy that the reader can’t help but to be drawn in to read more. Kimble leaves a fantastic trail of breadcrumbs to follow deeper into the narrative with bits and pieces of a well-fleshed out world, and the people and creatures within it. Near the middle the story falls into the comfortably worn wagon rut of a typical western story, but it maintains enough of the fantastical elements to not lose the magic it hooked the reader with in the beginning. The end stitches both genres together nicely, with a satisfying and not unexpected conclusion that neatly wraps up all the threads it introduced throughout.

In Rachael K Jones’s “The Fall Shall Further the Flight in Me,” Ananda has the weight of the world’s troubles on her shoulders and yet, she must make herself light enough to float through the air to heaven and carry her burden to the angels there. It’s hard, lonely work repenting that many sins, and the expectations of so many don’t make it easy, but when an angel falls from the sky—falls of all things—with an urgent message for Ananda, who could blame her for wanting to hold on to a little company? But a holy woman must not be attached. If she is to ascend and carry the prayers of the people with her, Ananda must shake off all the weight of her sins and carry only responsibility with her.

With a lilting prose style and fresh, breezy imagery, it’s easy to get lost in the clouds in “The Fall Shall Further the Flight in Me.” Told between in-the-moment scenes and Ananda’s idle speculation, the plot and the world unfold together with an in-and-out immediacy that keeps the reader attentive on the page. The characters and the world are steeped in myth and draped in dream in a way that easily brings fantastical images to the reader’s mind with only a few well placed words.

An old woman, two men, a pair of children, a pile of bones in a sack, and a cracked jar wander the wastelands together, in Patricia Russo’s “The Perfect Happy Family.” Mathie thinks the world smells like candy. The old woman’s mind is lost on sewing buttons, the jar now whispers when it used to talk, and the bones cry out their poor fate. As for Ched, he only wants to get back to the civilization he was banished from, no matter how many oddities he has to drag—or help—to get there.

Funny, clever and perfectly appetizing, “The Perfect Happy Family” is a vignette of a short story that nonetheless imparts so much information and meaning into the short word count it has. The characters are all unique and for the limited time that the reader has to get to know them, quickly become endearing. The prose and the premise linger on the border of the surreal, giving the interesting quirks of the characters a lot more mystery. The story is precisely as long as it needs to be, but when it finishes the reader is left with an instant sense of nostalgia, and a craving for more.

The leader of La Specchia has died and the city has been torn away from its mirror twin. Only the merging of La Specchia and its mirror-city’s respective Giovane can mend the two halves and make them whole again. Until then, every surface that can cast a reflection is covered, and no one may look at their own reflection. In Maria Brennan’s “The Mirror-City,” Mafeo runs through the reflectionless streets, dodging guards and running from the fate pronounced for him by the priests of the city. They say he is the Giovane, and he must save the city. It is a task he neither wants nor thinks he can complete, but fate, if it really does exist, cannot be run from.

“The Mirror-City” starts with lovely, descriptive prose and hints into the world and its mechanics before giving the reader a character who is likewise steeped in mystery. Unfortunately, before the reader has much time to become familiar with Mafeo, his fears or his motivations, he is pulled away by means that are insufficiently implied by the story. There seems to be a rich cultural background lurking behind the words in this story, but much of it is withheld until it’s too late to bring it to light with pleasing pacing. The climax rushes by without much meat for the reader to savor, and perhaps too many questions left lingering behind.

The Finch Oracle is about to be married in Benjanun Sriduangkaew’s “Finch’s Wedding and the Hive That Sings.” Between the court politics and social niceties, Anjalin, commander in the Fallbright Choir wishes for help in liberating her homeland of Therakesorn. But the Oracle won’t help Anjalin, and with the wedding drawing near and the new bride’s odd request to think about, Anjalin must go to the moon and back to bring the newlyweds the perfect matrimony gift—even if it kills them all.

“Finch’s Wedding and the Hive that Sings” is not a story that is easily understood. There is very little grounding in the familiar for readers to orient themselves. Names are foreign, world concepts are alien, and word choice frequently tumbles into the more obscure pages of the dictionary. Readers who enjoy science fiction that takes them completely out of the realm of what is relatable will find much to like in this story. Others may find themselves scratching their heads, especially with the many sharp, tangential twists the plot takes. The prose and imagery however is lovely enough to keep most readers interested until the end.

Sometimes when we experience the death of a loved one, it changes how we see the rest of the world. This is the case for one individual alone riding a packed train in Rob Cameron’s “Squeeze.” Frolicking among the living, one small ghost has the power to stitch lives back together and perhaps mend some wounded hearts.

“Squeeze” is a wonderfully powerful story for its short length. The descriptions used are thoughtful and evocative, with a lovely literary tint mixed in. Cameron made the interesting decision to write the story in first person point of view that skirts along the end of second person, giving the reader the impression of being another ghost riding in the train with the protagonist. “Squeeze” is the sort of story that is so well written, it would work just as well without the ghostly element, although it would lose some of its bittersweet charm.

Katrin’s suicide was hard on Dana, in “A Guide to Birds by Song (After Death)” by A. C. Wise. There was no note left behind, only a typewriter with a story locked inside of it. As Dana frantically types out the story in birdsong she attracts the notice of an angel who has the potential to make things much better or unfathomably worse. Through all this, Gabrielle watches her lover work herself to madness to free Katrin’s story while supernatural forces gather to convince her that she and Dana both are being haunted.

“A Guide to Birds by Song” is a fractured, chaotic narrative that intentionally leaves the reader grasping at ephemeral feathers for meaning. Although by the latter third of the story the narrative begins to clear up, the beginning and the middle are dream-like and hop between points of view such that the reader isn’t sure who is who and what is happening. The final reveal isn’t unexpected, however, and leaves the reader internally savoring the ride, while belatedly processing all the beautiful imagery they had passed in the scramble for understanding.

Isi has a gift of far sight that has earned him quite the reputation around his village. But in Gray Rinehart’s “The Sorcerer of Etah,” a series of strange events rob him of his ability and put him in mortal danger. First the birds arrive too early from their southern migration. Then the moon eclipses the sun and casts the frozen world into darkness. Finally his mother appears before him, back from the dead, just as spiteful as she was in life, and promising Isi’s destruction.

“The Sorcerer of Etah” takes place in the culturally and geographically intriguing arctic, a setting that is unfortunately underexplored in fantasy and science fiction. Rinehart brings it to life with vivid mythology and imagery that puts an immediate chill in the reader’s bones. The pacing is wonderful, although the reveal is sudden and a tad bit under-explained compared to the rest of the story. Nonetheless the climactic fight scene is gripping and ends the story with a sense of hard-won accomplishment in an unforgiving landscape.

There’s a new super villain in town in Sam Fleming’s “The Prime Importance of a Happy Number,” and he’s up to some grand and dangerous pranks. It’s nothing especially new to Kenneth Mackenzie, though he is getting far too old to deal with these shenanigans on his own. Fortunately he’s got a very capable staff on his side, not to mention the literally explosively talented Audrey. Whatever this new magical miscreant wants, Kenneth is prepared to deal with it, with strength of experience if not with raw power.

“The Prime Importance of a Happy Number” starts strong with a great deal of humor and a fast, enjoyable pace. Unfortunately this pace stumbles near the middle when the cast of characters is introduced. The casualness of their introduction suggests that the reader ought to be as familiar with these characters as they are with each other. After the giddy pace of the introduction, this switch forces readers to slow down and reread to make sure they haven’t missed anything crucial. This style choice continues through to the end of the story, leaving the reader feeling as if there is an inside joke, or perhaps a larger world narrative that they have missed, which would help them understand the details of the climax and the denouement.

In “Social Visiting” by Sunil Patel, Shaila is vexed by the annual need to visit a circuit of extended family, drink tea and eat pastries until she is full to bursting and near tears with boredom. All that will change on the year of her sixteenth birthday, however, when Shaila and her cousin Divya uncover the mystery of the return of the demon Ravana who is prophesised to kidnap a young woman if someone with extraordinary power does not stop him first.

“Social Visiting” is a supernatural young adult fantasy hinged on Hindu mythology. Unfortunately, large parts of it feel as though they have been cut away, leaving the narrative to unfold gracelessly in chunks of clunky exposition and lengthy tangents that rob word count from a more artistic introduction to the Hindu mythos. Many of the plot events outside of the supernatural are farfetched, and the parts pertaining to magic, demons and protection spells are rushed and under-explained. “Social Visiting” has a wealth of cultural history, both ancient and modern, to draw from. Unfortunately the story itself suffers from poor narrative delivery that drains the mythology of all of its charm.

Morgan is dying in “The Book of May” by C. S. E. Cooney and Carlos Hernandez, but that doesn’t mean that she’s done with living. She has big plans for her afterlife. Namely, she wants to be a tree. With a little support and help from her friend and D&D companion Harry, Morgan prepares for the end, while pulling Harry with her down the final, magical spiral that is her life.

“The Book of May” is a sweetly heart breaking story about reunion, reconciliation and the pain of losing a loved one. Harry and Morgan both feel very alive and very real on the page, and this impression is only helped by the email and instant message vector of narrative delivery. Because of the lengthy set up, when the story does take a turn into fantasy, it feels as though it comes too late to fully integrate into the story. I felt the line between the realistic and the fantastic was never completely breached, especially since the email in which it is first discussed reads like a private roleplay between Harry and Morgan. The final two emails of the story cast this assumption into doubt and leaves readers wondering what was missed between the two friends’ communications that might more concretely tie the fantasy elements into the rest of the narrative.

In Holly Heisey’s “The Tiger’s Roar” Evin is a gifted artist in plant sculpture. His ability to coax them into specific shapes and designs comes not just from natural talent. Evin has a deep, dark secret. He has the outsourced soul of a noble living within him, something he would very much like to keep hidden. But when a soul hunter shows up at his father’s estate with a keen interest in his artwork, Evin knows there’s no way to keep his secret hidden. What’s worse though, is that there’s no way of knowing what the hunter will do with the knowledge she finds, or what the consequences will be.

There are several interesting concepts hidden throughout “The Tiger’s Roar” though most of them are underdeveloped on the page. Whether this is an issue of poor pacing or word count conservation, details about the necessity of the talismans, soul outsourcing, the abilities of the hunters, and the specific social and political place of individuals with second souls are conspicuously under-explained. With so much of the driving force of the premise left up to reader speculation, interest in the characters and their problems quickly wanes under the uncertainty that they are in any real danger at all.

In the middle of a scorching summer in the city, nine year-old Malka Hirsch makes friends with thirteen year-old David Richards. David is just like any other boy she’s known, except that he’s dead of course. As children often do, their innocent conversation ends with Malka inviting David to her house for a Sabbath dinner, never mind that her father has given up anything that has the smell of religion in it. But Malka wants to share a bit of her forsaken culture with her new friend and in the end, her father can’t find reason to refuse her. They have everything they need except for kosher wine, and in the prohibition era in which they live, that is going to be very hard to find.

Barbara Krasnoff’s “Sabbath Wine” meanders throughout the story, but this nonetheless doesn’t stop it from being interesting. The characters are unique and fleshed out and the setting provides an interesting bit of conflict for everyone in the story. The reveal is in its way surprising; however the general tone of the story takes a sharp turn at the end, making the final line in particular feel ham-handed by comparison.

In “The Trinitite Golem” by Sonya Taaffe, J. Robert Oppenheimer sits in his office, contemplating the path his life has taken and the more than probable FBI surveillance hidden in the ashes of what his life has become. Once a respected scientist, he now lives in disgrace, which is to say nothing of the weight of his conscience, a weight that is given life in the form of a glass golem with an unusual request that Oppenheimer, who has become the destroyer of worlds, cannot honor.

“The Trinitite Golem” requires a lot of foreknowledge in the history of the nuclear bomb and religious mythology to understand the story completely, however if readers are willing to do a bit of digging where their understanding is incomplete, the rewards are worth it. The two introductory scenes are snappy, with sharp, tone setting prose, giving the backstory of Oppenheimer in a linguistically pleasing style. The actual plot is much more subdued. The dialogue between the characters is almost incomprehensible if the aforementioned knowledge is lacking, but Taaffe gives readers enough of a sense of a man hopelessly dogged by his past that the emotion evoked becomes its own understanding.

To see the surfaces of Superior and Inferior Venus is the goal of the Chinese and Baghdad space mission that sent Irunn to the burnt out planet in “Two Bright Venuses” by Alex Dally MacFarlane. Unfortunately to do so with any hope of surviving with her sanity, Irunn must be split into two people, to descend to the twin planet at the exact same time. Yet the closer superior and inferior Irunn get to the planets’ surfaces the more they are assaulted by a strange, indescribable, unavoidable, full sensory song. Unable to ignore the planets’ plaintive dirge both superior Irunn and inferior Irunn must perfectly coordinate their descent, or loss of their sanity may be the least of what they have to worry about.

“Two Bright Venuses” takes a very careful reading to understand. Irunn, being split, talks to herself in fractured thoughts, as one tends to do inside one’s own head. The two Venuses only add to this fractured narrative delivery with their own barely comprehensible song that both Irunn’s struggle to describe throughout the story. While trying to understand the premise, small details such as previous missions and where the characters are in space and time are swallowed up. Readers are advised to read this story slowly and carefully to absorb every detail for full understanding.

The relationship between brother and sister is complicated in Shveta Thakrar’s “By Thread of Night and Starlight Needle.” The witch Rekha can see that plainly when twins Kiran and Sanjay visit her home with a request. It’ll take some prodding, and some looking into their past lives for all three of them to see that what the brother and sister want are no longer the same thing.

In four short narratives and an excerpt from a poem, Thakrar attempts to paint a picture of cosmic destiny between Sanjay and Kiran. Unfortunately, without a clear linkage between these five narratives, the whole story feels cluttered and unfinished. The main arch is unresolved and the reader is left not knowing which option—that the twins should stay together or separate—is the correct dharmic decision.

It’s Yavena’s fault that her older sister Iraline will die at the hands of the Gak in “The Games We Play” by Cassandra Khaw. She knows this, which is why she’s willing to fight her way through each game of the Court of Death to play a final round of cat and mouse with the Dog King. If she wins, she and Iraline go free. If not, Yavena takes her sister’s place. Unfortunately, Iraline has her own reasons for wanting to be the Gak’s sacrifice and time is ticking quickly by to convince her otherwise.

Khaw crafts an interesting world and lore in “The Games We Play.” The interplay between the Gak and the Ovia unfold slowly throughout the narrative, keeping the reader guessing and searching between the lines for meaning. Very little is explicitly explained in the story and many of the crucial details can slip by unnoticed to a casual eye. Despite this, the story ends up feeling satisfactorily concluded, coming more or less full circle, even if it doesn’t fully explain the circumstances that led up to that point.

In the morning, the Beasts walk past the village with baskets full of the dead and in the evening they walk back in Keffy R. M. Kehrli’s “The Road, and the Valley, and the Beasts.” No one knows where they come from—presumably from the place the babies come from—and only one seems to want to know. But her lover Ria’s curiosity runs along a different path. She wants to know where the Beasts go everyday. Where they lay the innumerable bodies of the dead.

“The Road, and the Valley, and the Beasts” is a very short story that a reader can easily skip through without latching on to any meaning. The ending is jarringly abrupt, such that, at first glance it appears as if only half the story has been printed in error. However tiny details give the picture of a broader story between the lines, if the reader takes the time to look. And if not that, the prose flows very well, giving the reader a short, pleasant journey.

Four Warm Currents is about to make a breakthrough, literally and figuratively, in “Innumerable Glimmering Lights” by Rich Larson. For cycles he and his team have been drilling through the ice roof of their ocean world, for science, for the spirit of exploration, for fame. But Four Warm Currents isn’t without his opposition. Many in the City of Bone have expressed their fears that the excavation will cause the end of the world, and with every inch closer to the secret beyond, the outspoken faction grows and becomes more violent.

“Innumerable Glimmering Lights” is a great, otherworldly tale that closely mirrors contemporary society while being very distinctly ‘other.’ The alien world is strange but not indecipherable and the parts of it that are anthropomorphic make the characters instantly relatable and recognizable. The tension is hot and fast, and the climax boils in a wonderful explosion of all the pent up emotion built throughout the story. While “Innumerable Glimmering Lights” doesn’t break any literary boundaries, it most certainly is a story well worth the read.

No one knows horse souls like Ilsa. In “The Souls of Horses” by Beth Cato, she can feel what they want just by touching the soul, or the vessel the soul resides in. So when Confederate Captain Mayfair steals the carving holding her beloved horse Bucephalus in order to blackmail her into imbuing horse souls into metal equestrian automata, Ilsa is nearly mad with grief. She’s lost too much in her life to lose Bucephalus too, but as the war heats up she’ll have plenty of work to do to keep her mind occupied on other things.

The writing style and the prose itself are lovely and flow well together in “The Souls of Horses.” The premise likewise is enjoyable and refreshing in the setting. However the setting and its relationship with the characters is where I feel Cato loses some of the impact of the story. The principle actors in the story all feel too soft and clean. Given the specific choice of setting, the lack of tension between the characters is conspicuous and gives the overall plot a presumably unintended Disney feeling. While arguably the point of the story isn’t race relations during the Civil War, what watery conflict the story has is partitioned into unexpected avenues, leaving the impression that perhaps a different setting might have told the story better.

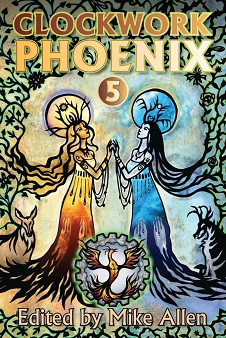

Clockwork Phoenix 5

Clockwork Phoenix 5