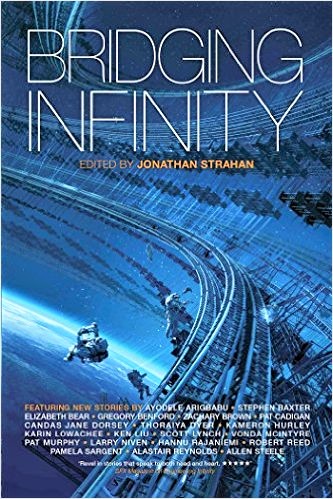

edited by

Jonathan Strahan

(Solaris, November 2016, 356 pages)

Reviewed by Jason McGregor

Over the course of reading Bridging Infinity, I had to re-read the introduction a couple of times to make sure I had it right. Strahan defines the “sense of wonder” and the “sublime” and then “began to wonder if there could be such a thing as a mechanical sublime, an engineering sublime” while also positing a key element that’s dear to my heart: “that problems can be solved.” So far, so good. But then he also says “[t]he only criteria was that they be hard SF and relate to a super engineering project or projects” and that “Bridging Infinity isn’t a climate change book.” But, in the course of reading the book, I became convinced that the “bridging” referred to multi-generational stories and/or life-extension techniques and that this practically was a climate change book and that this was even somehow a “sunshade” (or “orbiting sunscreening mechanism”) theme anthology. If the true criteria is simply “super engineering hard SF” then this is way too redundant an anthology and once or twice even uses “hard SF” in the loose sense of “focused heavily on SF tropes” rather than in the strict Hal Clement sense.

I was very excited to have an opportunity to review this, as it’s from a big name publisher and a big name editor and a roster of mostly big name authors and is explicitly about SF and sensawunda and big engineering. Had it been none of those things, I suppose it’s a fine anthology. But given that it was supposed to be all those things, I was quite disappointed. There’s little truly bad here but little truly good and perhaps nothing great. With reservations ranging from mild to major, I’d recommend the Liu, Murphy/Doherty, and Benford/Niven, though there was also interesting work by Steele, Baxter, Reed, and perhaps Lowachee. Generally, this anthology included a lot of death and disaster and human-hating with climate change being the Favored Way Humans Screw Up and several of the stories just included a Big Engineering Project in order to qualify but really didn’t care about it and instead talked about other things.

“Sixteen Questions for Kamala Chatterjee” by Alastair Reynolds

This could be a story about a woman discovering an anomaly in the sun which turns out to be an alien artifact. She could eventually be given life extension treatments and be bioengineered into para-human forms in order to survive on the surface of the sun as exotic materials are used to construct a bridge from the surface to the anomaly. Would that it had been. Instead, it is a “literary” piece written in the form of the sixteen questions for the doctoral candidate of the title (apparently in two slices of the multiverse). So, while it mentions all those ideas, the actual story is about a woman sitting in a room being asked questions until she comes to a decision about pursuing her doctorate. Which, granted, has implications for the survival of the human race.

This may work for you, especially if you enjoy multiverse stories (which seem to me to make everything absolutely meaningless) or if you enjoy fun ideas being obfuscated by several G’s of artifice, but I just really wanted the story to focus on the actual idea content regarding a single universe in a straightforward narrative. But this clearly wasn’t Reynolds’ goal and he seems to have achieved what he set out to do (allowing that the alternate universe is implausibly and confusingly woven in) so, if that’s what the reader wants, the reader may be pleased. But this reader, despite generally being a big fan of Reynolds’ short work, wasn’t.

“Six Degrees of Separation Freedom” by Pat Cadigan

Dory is a civil engineer who helps with a lecture and has a conversation with Reka, then has a sort of meeting as well as another conversation (both in Kyrgyzstan) with Revere, and finally climaxes with a conversation with Carleen. During these talks, everything from engineering social structures, modifying human bodies for life in space, advertising pressures, gender modification, human pinball, and more, is discussed.

This may have some clever structure and thematic connections that I’m missing but this really just felt like a grab-bag to me or, perhaps, part of a larger fictional structure which might have more meaning in that context. It does seem to be set in the same universe as her award-winning and infinitely sprightlier “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi” though it doesn’t especially connect to it beyond a reference or two and some concepts. Taken purely for itself, this was not exciting in terms of plot or style. Considered in the context of this anthology and Cadigan’s other work, this was the second of two stories by an author who’s written numerous pieces I love but which disappointed me.

“The Venus Generations” by Stephen Baxter

In one of Baxter’s Poole stories (a subset of the Xeelee stories), Jocelyn Poole is set on terraforming Venus by freezing out the carbon dioxide with space-based solar shields. Her daughter, “Hank,” doesn’t like the plan as it messes with the cities floating in the atmosphere and with the native life there. Eventually, her son and Jocelyn’s grandson, Pierre, doesn’t like the plan either, as he’s studying alien nanotech which he believes can more efficiently terraform Venus. Jocelyn is obviously opposed to her daughter but also to her grandson as she believes relying on this alien tech is a betrayal of human nature. This family drama takes place over many years, as all have had life extension. The resolution, involving some aphrological instability, results in a sort of closure while indicating the ultimate path in a thematically significant way.

Per the paragraph above, this is full of nifty ideas and is well done in ways but there are flaws. The “action climax” (so to speak) feels somewhat gratuitous (a case of author fiat) and trite, as does the family dynamic at the end. Prior to this, none of the characters are particularly likable. There are even a couple of odd glitches: Jocelyn does something involving “Hank” when it should clearly say “Pierre” near the end and, at one point, she “had lain down” some CO2 when it’s my understanding (even for non-US English) that she might have lain down, but the CO2 would have had to be laid down. In sum: not great but not bad.

“Rager in Space” by Charlie Jane Anders

A couple of young party girls end up in a spaceship run by an AI which is debating with a couple of ET AIs about whether or not to wipe out the human race after an apparently failed Singularity.

This opens with a structurally perfect joke paragraph (which made me “LOL”) but quickly descends into an overdone valley girl sensibility that inconsistently wobbled into moments of pathos or actual interest but mostly seemed too silly. It’s possible this will appeal to some but I doubt it would to very many. For a “teen girl tries to save the world—a lot” experience, I’d recommend watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer instead.

“The Mighty Slinger” by Tobias S. Buckell & Karen Lord

In the far future, because Earth is nearly uninhabited and uninhabitable, we will be living on Mars and elsewhere throughout the solar system while also living on and mining the asteroids to form a Dyson ring. There are powerful people and interest blocs jockeying for power and position, ultimately leading to war. Some people get to live through all this and see vast changes occur over time due to a Karl Schroeder “Lockstep”-ish sort of cold sleep process (which also reduces drain on resources).

So, naturally, this story uses this scenario to talk about a calypso band (day-o!) and its part in changing the solar system due to some well-placed extemporaneous lyrics and one large piece of misdirection (which uses the exact same principle found in another story which I won’t identify to avoid spoilers).

As near as I can figure, that’s actually what the story is about and, unlike the Anders, it’s all done with the utmost seriousness with many awkward attempts to wax musically transcendent in print which almost never works and doesn’t here.

“Ozymandias” by Karin Lowachee

A very non-military guy with a checkered past, working for subcontractors, has finagled his way into a job onboard a military “light station” (or lighthouse/waystation in another system’s space) to babysit the AI there as it works on finishing the partially completed structure. After a brusque meeting with the person who preceded him in his duties, she leaves and he’s supposed to be alone, though it turns out he’s not. Identifying and dealing with the intruders forms the crux of the plot.

This story has some odd writing (the opening paragraph, a later inverted phrase) and errors (e.g., “[s]hould anything go wrong and [the AI] became unable to fix it…” and “[h]er tone held a gravitas that didn’t jive with the statement…”), a contrived premise (why not have multiple AIs back each other up rather than a human?), and doesn’t amount to much (when the ending arrived I had a surprised “That’s it?” reaction) but it’s adequate and has some nice description, a sympathetic character, and puts the reader in a tangible place with some things to learn and do.

“The City’s Edge” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

This is a meditation on death, loss, and continuance, told in the form of a Petras examining the location of his wife Hedie’s death, which had been the site of the flying domed city she’d designed and the construction of which she was supervising. One night, the city just disappeared and her body and 600 others were found at its former site. Petras realizes this may not have been the first such event and what that may mean but still has to deal with immediate things.

This story is not my cup of tea and it’s unfortunate that it has to be a basically negative tale of mega-engineering (with a kind of gimmicky element, to me) but it’s competently done and well felt and may appeal to many.

“Mice Among Elephants” by Gregory Benford & Larry Niven

The story (set in the Bowl of Heaven/Shipstar universe) eventually reveals that the title expresses humanity’s relationship to some aliens and perhaps even then-current human consciousness to the cosmic scheme of things, but it could equally well apply to the plot in relation to the milieu. Perhaps this is intentional and clever but it didn’t hit me that way. The plot is quite simple and modest: go explore an object and suffer some relatively mild consequences. But the milieu is quite the wonderland with paltry humanity having to make do with ramjet starships, a few crew members revived from cold sleep, “Artilects,” and even “the Diaphanous” in the form of Daphne and Apollo, two sentient, intelligent “knotted plasma patterns” or “smart toroids” that evolved in Sol. The object we primitives, with our electromagnetic communications, are investigating is a gravwave emitter made of a network of micro-blackholes that the natives of the Glory system have manipulated for their own purposes. And these are just some of the toys in the window.

As I say, the plot-mouse skittering around under the milieu-elephant isn’t entirely satisfactory and, indeed, some people who are allergic to polysyllabic expressions of sci/tech wonders will find little here, but some will respond to the modern poetry and feel like kids looking under the Christmas tree. This story is at least focused on its crew, its concretely described starship, and the gravwave emitter and is not just supplying a gimmick to meet the requirements of the theme while actually being interested in other things. Not an entirely successful story but the first one in this book that seemed to really meet the brief and that I really enjoyed.

“Parables of Infinity” by Robert Reed

In another displaced narrative, we are told a story by Pamir being told a story by a “tool” (which is to say, in this case, an ancient AI-like construct from outside the Milky Way). The story is of hyperfiber (a multi-dimensional material) being used, along with the contents of a star system, to build an even greater ship perhaps even longer ago than the Great Ship they’re both currently on. Along with being a parable of infinity, it’s also a parable of putting all your eggs in one basket and then playing chicken, so to speak, with a black hole.

Reed’s Great Ship series is one of the major series in recent and current SF but the stories engage me with only varying success. In this case, we certainly have the big ideas and Reed does a very good job of controlling the story’s tone and general style but the sort of cold, distant narrative left me somewhat cold and distant. But some readers may find this to have been “a beauty.”

“Monuments” by Pamela Sargent

An AI narrates the story of three generations of hereditary female “Governors” of “New York” in a future of the virtual extinction of humanity (and everything else) through climate change. The eldest had started a project of cooling the Earth via orbital “sunshades” (there’s that again) and the youngest can’t even live to see it through to completion, though the AIs should manage—completing it in a way not intended by the founder.

Anyone who has fought insects and vegetation from March to December lately will sympathize with the youngest woman’s desperate desire to experience snow and frost and some may enjoy more finger wagging at worthless evil humanity for all that we destroy. About all I can find to praise in it, though, is that it is a tonally controlled tale and structurally sound enough. But it offered nothing of originality or anything unoriginal that was good to experience again.

“Apache Charley and the Pentagons of Hex” by Allen M. Steele

The latest of Steele’s Hex stories might be a tale about growing old or the grass being greener on the other side or “the chase is better than the catch” or something like. If you’ve never read a Hex story, you’re in for a treat and I have some explaining to do but, if you have, you may well be disappointed again at an under-utilization of a great idea. Basically, an alien race has constructed something that isn’t a Dyson sphere but is a sphere 2 AU around, composed of six trillion hexagons (and a few pentagons), each composed of five or six things that aren’t O’Neill cylinders but are 100×1000 mile biopods which give each hex a planet’s-worth of habitable area. The aliens then invited most other aliens to live there. It’s basically the universe in (really huge) miniature. (Steele does a better but somewhat longer job of describing it in the second section’s infodump after the first section’s hook.) The story involves some “joyriders” (people who wander around Hex on their own, outside the government-approved corporate auspices), including the title character and the fixation he has with finding and exploring the title objects—the few items holding Hex together that aren’t hexagons. There’s not much more to be said about the basic gist of the plot without spoiling things.

While I started laughing vigorously upon reading about the joyriders like Genghis Bob (which is as classic as “Sorcerer Tim”) and Marie Juana and their wandering minstrelsy and card tricks with the aliens and really started losing it when reading about them affixing telepathic lemur-like alien critters to their heads to better communicate with some other aliens, and think Hex beats the pants off of most of the other Big Ideas in these stories, I can’t in good conscience say “Apache Charley” is much better than the other stories. It’s very similar in ways to the calypso band story. If you like the calypso band story, that’s great; I didn’t. If you don’t like the joyrider story, that’s okay, but I (mostly) did. But I don’t suppose either can really be argued to be generally great.

“Cold Comfort” by Pat Murphy & Paul Doherty

A rogue scientist bounces around in the Great White (but Greening) North with a semi-plan to create “methane sequestering mats” out of carbon tubes filled with methane metabolizing bacteria. As methane is an even “better” greenhouse gas than CO2, and truckloads of it are released when the not-so-permafrost thaws, this could be very useful. But no one listens to the scientist’s proposal until she engages in a little mild, discreet ecoterrorism in the sense of blowing up a remote frozen lake and getting people worried about permafrost and methane. With key people not knowing she’s responsible, things begin to break her way and she sets about trying to save the world via crowdfunding, musk oxen, robots, and less likely things. The problem arises when the political climate of the US changes and has disastrous effects on the ecological climate (not that that could ever happen here) and her research station is shut down and she’s slated to be arrested for, y’know, saving the world and working with foreigners and such. Ever resourceful, she runs off and hides with plans to return when it’s safe. We pick up 30 years later for our cold comfort, the precise nature of which I will let readers discover for themselves.

This story could be criticized for lacking sufficient dramatic tension (regarding the character in the story, not regarding trying to save the world from mass extinction) and I don’t personally quite like the ending (nor am I supposed to) and this is yet another example of “cli-fi” and is otherwise a good story and superior in most every way to “Monuments” in that it has an interesting narrator, is packed with nifty ideas and details and ramifications and interrelations, and has an actual problem-solving bent and is simultaneously bitterly cynical and yet doesn’t simply classify humans as generally repugnant. It could be better and doesn’t necessarily fit perfectly in this anthology (despite the idea of vast constructed mats and so on, technically fitting) but it’s definitely one of the better stories here.

“Travelling into Nothing” by An Owomoyela

Kiu is awaiting execution for murder on a world not originally her own when she receives an unexpected visitor with an unexpected possibility of at least reprieve. All she has to do is accompany the stranger as pilot to a ship which drives a planetoid towards an arcology hiding in interstellar space. She is (approximately) suitable for this task due to her “artificial neural framework” which was implanted in-vitro. Having no better options, she agrees. The interface to pilot the ship is psychologically traumatic and she seems to be unable to pilot the ship properly. After repeated attempts, she gives it one last try.

And none of the above much matters. It’s a literal synopsis to a thematic/symbolic story in which the stranger, Tarsul, outright says the “this isn’t hard SF” line of “I don’t pretend to understand the intricacies,” when “explaining” the nature of the ship and, while in the interface, a manifestation says something to Kiu and the narrative voice says “[t]hat didn’t sound like something Kiu was meant to understand. She moved past it.” This appears to perhaps be about people who are different being treated poorly, which engenders rage which results in the different people hurting themselves (perhaps fatally) if they don’t transcend it. Or perhaps not. Perhaps I’m not meant to understand and I’ll move past it. This may appeal to some as it is certainly vividly described (albeit in an “impressionist painting” fuzzy pastel kind of way) and is much more emotionally intense than many of the stories in this anthology and attracts the reader’s attention. But the contrivances of the story on a literal level and the whole “metaphoricalness” of it may turn off even those who were interested.

“Induction” by Thoraiya Dyer

An evil guy, his wimp half-brother, a woman who does not conform to conventional standards of beauty, and an old woman with dementia await a vast wave created by the displacement of water from the melting ice of the poles which will actually create a rebirth of the island they all lived on at various times prior to this point. The wimp is the downtrodden hero of the tale and the younger woman is the heroine and the evil half-brother’s plan takes an unexpected twist at the end.

This story starts with a long set of definitions of the various meanings of “induction” and includes a sort of report extract in the middle and, despite its rather inauthentic ending, is very depressing and unpleasant. While it has a not-small-scale engineering project, no real sense of wonder is created. And I do not understand the editorial choice of selecting so many climate change stories and really do not understand the editorial choice of so heavily backloading them together, with three out of the last five. But perhaps “cli-fi” fans will find something in this to enjoy.

“Seven Birthdays” by Ken Liu

This story covers Mia’s life in seven snapshots, from her 7th birthday to her 823,543rd. Kites of wildly different magnitudes and mothers of wildly different substrates figure prominently. She moves from her mother buying time for the Earth from climate change (that again) by very modestly doing an atmospheric chemical dump to lessen the sun’s radiation effect on Earth (rather than using the space-based sunshades favored by several other authors in this anthology) on to her own perfecting of mind uploads (which allows her digital descendants to argue about how much of an environmental impact their data centers should be allowed to have) on to Matrioshka brains and Shkadov drives and more.

While this story doesn’t seem to be as free from a sort of historical dualism (which leads to a tincture of human self-loathing which is mostly balanced by an explicit appreciation of our “wondrous” quality) as it is from the human vs. nature dualism that it explicitly disavows and does seem like yet another climate change story at first, it does move on to bigger and better things which do involve mega-engineering and a bit of “gosh wow” and is a good execution of the tried-and-true and fitting “time lapse” structure. I can reservedly recommend this.

Jason McGregor‘s space on the internet (with more reviews) can be found here.

Bridging Infinity

Bridging Infinity