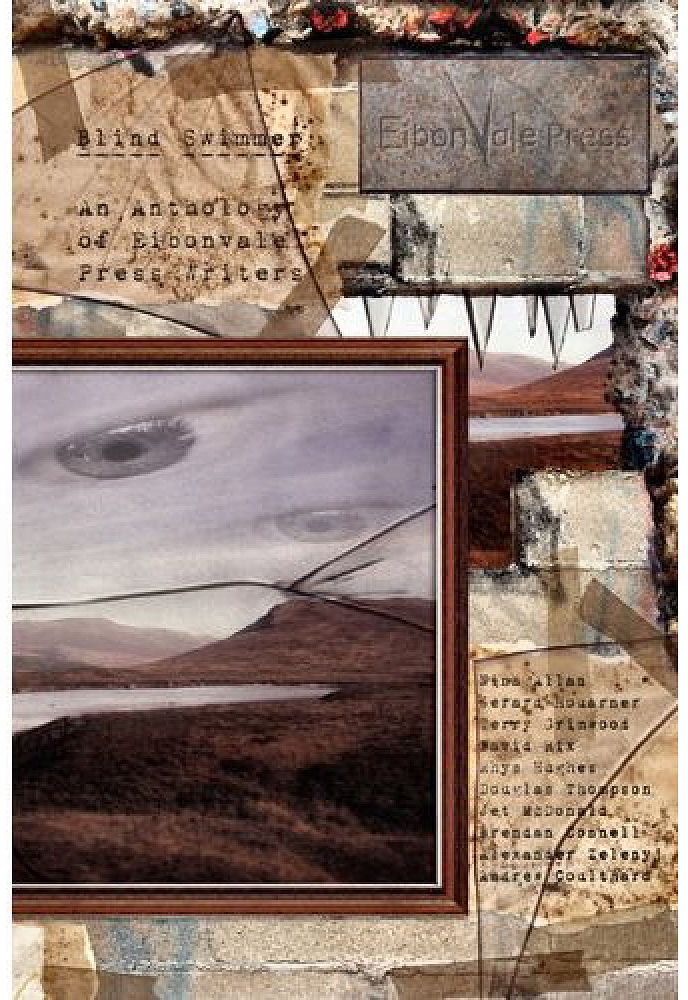

Blind Swimmer, edited by David Rix

“Bellony” by Nina Allan

“The Flea Market” by Gerald Houarner

“The Talkative Star” by Rhys Hughes

“The Man Who Saw Grey” by Brendan Connell

“The Book of Tides” by David Rix

“Flights of Fancy” by Allen Ashley

“Pigs Eyes” by Jet McDonald

“The Flowers of Uncertainty” by Douglas Thompson

“The Higgins Technique” by Terry Grimwood

“Far Beneath Incomplete Constellations” by Alexander Zelenyj

“Lussi Natt” by Andrew Coulthard

Reviewed by Rena Hawkins

In his new anthology, Blind Swimmer, editor David Rix poses the question, “What effect does isolation have on creativity?” In the eleven stories that make up the anthology, many of the main characters willingly choose to isolate themselves, while others have isolation forced upon them.

The anthology opens with “Bellony” by Nina Allan, by far the best story in the collection. Terri Goodall is a newly single freelance writer who sets out to write an article about her favorite childhood author, a reclusive woman named Allis Bennett who disappeared without a trace from the small seaside town of Walmer many years earlier. Terri immerses herself in Allis Bennett’s strange world, going so far as traveling to Walmer and renting the author’s former home. The truth she uncovers about Allis Bennett is stranger than any fiction.

Allan does a masterful job of slowly, skillfully drawing the reader into her mystery. I believed in Allis Bennett as an author and could easily envision the peculiar children’s books she wrote—I imagined her as a sort of female C.S. Lewis. My minor complaints are that Allan sometimes forgets the “show, don’t tell” rule, narrating heavily on what Terri thinks, sees, and feels. Also, the senior Mr. Cahill seems to pop up out of nowhere with a huge amount of pertinent information. However, due to the success of the story as a whole, I overlooked these small flaws.

“The Flea Market” by Gerald Hourarner, introduces Derrick, a Vietnam vet who is alone not because he chooses to be, but because his entire family is dead. Derrick fills his lonely hours by searching through flea markets and second hand stores looking for rare albums. Derrick discovers what appear to be handmade album covers in a flea market stall and is startled and confused when the artwork on the albums awakens memories of the people and dreams he thought he’d lost.

An odd story, but I found the portrayal of Derrick’s loneliness to be the most realistic of the whole collection. Derrick reacts to his loss and loneliness the way many people do—he ignores his feelings and fills his days with endless, meaningless tasks so he doesn’t have time to think too much about what’s missing in his life. There’s a truth in this story I didn’t find in many of the others.

“The Talkative Star” by Rhys Hughes is a series of vignettes or flash fiction about what the sun might say in various humorous situations.

There is a sentence in the next to last vignette that reads, “Yes, it’s me! I’m tired of your whimsical nonsense and I want to shut you up.” The author’s own words precisely sum up my feelings about this story.

In “The Man Who Saw Grey” by Brendan Connell, Greg Schwegler, a man who yearns to be an artist, hits his head in a fall and loses his ability to see colors. His whole world becomes shades of gray.

I was bothered by the dialogue between husband and wife, which throughout the story is oddly formal, as if they don’t know each other very well. In fact, the wife, Cassie, has a sort of Stepford Wife complacency about her husband’s condition that I found extremely strange.

Although a great deal is made of Schwengler desperately wanting to be a painter at the beginning of the story, he seems more upset about the appearance of his wife’s naked body, animals, trees, and parks than he does about his inability to create art. In fact, the story could be written without any mention of his being a painter at all, so why focus on it? I never became emotionally involved in this story and I wasn’t particularly shocked by the ending.

Editor David Rix is also a contributor with his story “The Book of Tides.” A man (he never has a name) lives a solitary life on a beach, spending his days collecting debris from high and low tides and writing stories about what he finds, giving the items imagined histories. When a young woman, Feather, lands on his beach, he eventually brings her home as well. Feather, however, proves to be a troubling presence and threatens the peace of his solitary existence.

I found this a very confusing story full of stilted, stammering dialogue. There’s no consistency in the reactions of the characters; when the man initially finds Feather and thinks her dead: “He shuddered at the implications of a death on his doorstep. People would come—wanting to talk to him. The police would have to clear the mess up and his isolation would be shattered.”

Yet, later in the story, neither he nor Feather is particularly troubled when five corpses wash up on the beach. No big deal, right? In fact, Feather searches the dead teenagers’ pockets, saying: “If there is anything interesting on them, you can put it in your novel.”

I understand the man and Feather are supposed to be “disassociated” from the outside world, but this just comes off as ghoulish.

The main characters in “Flights of Fancy” by Allen Ashley are Kris and Josh, two men isolated in a prison on a small, Scottish island. Kris fills the long hours by writing a story about a wizard and a knight trying to escape the castle of an evil king. As “Flights of Fancy” unfolds, we learn through the prison guards and the warden that there is a growing crisis in London and surrounding cities involving a strain of bird flu and of the frightening changes the flu vaccine has brought about in the local bird populations. Kris, Josh and the other inmates are increasingly cut off from what little information they receive from the outside world. As the bird crisis worsens, conditions in the prison grow more and more deplorable.

This is my second favorite story of the collection, a complex tale of reality, fantasy, conjecture, and isolation within isolation. Is the construction of the story perfect? No. But Ashley’s forethought and planning are obvious.

“Pigs Eyes” by Jet McDonald is the story of a woman who sells fried pig eyes for a living and falls in love with an overweight, agoraphobic, would-be writer who disappears into a coconut.

If you think my synopsis sounds ludicrous, you’re right. I have utterly no idea what to make of this story and I refuse to pretend I do. The emperor has no clothes.

“The Flowers of Uncertainty” by Douglas Thompson introduces Harold Swimmer, a brilliant writer whose first book was so successful, both critically and financially, that he has decided to isolate himself on a lone stretch of beach for thirty years so as not to be poisoned or influenced by the outside world while he writes new books. The only person Harold comes in contact with is Sharon, a woman who provides for his needs and delivers his finished manuscripts to his publisher. She never speaks, as Harold has instructed. When Sharon disappears, Harold’s imagination goes into overdrive.

All I will say about the action which unfolds is, fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. Fool me three times, I’ll stop reading your story.

Life attempts to imitate art in “The Higgins Technique” by Terry Grimwood. In order to write a story about internet rape porn and hopefully restart her flagging career, Emma answers a “model call” and becomes internet porn’s newest face. Geoff, the porn director, hates what he does for a living and dreams of making “real” films, but hey, the money’s good. Tony, the porn customer, requires a plot with his violent images in order to get off. Lilly, Emma’s dead baby daughter, hovers over the story unseen, but very much present.

Although many people would question the “creativity” of porn, the isolation of the characters is clear. Emma is isolated from her emotions, from the pain and guilt she feels over Lilly’s death. Geoff, the director, is isolated more and more from the hopes and dreams of his youth. Tony, the customer, is physically isolated from real women and actual relationships, choosing to masturbate alone in front of his computer while imagining his ex-wife.

I found myself wishing the author had left the dead baby out of this story and gone in a more unpredictable direction with Emma. It’s tiring to always read about women portrayed as the tragic victim. The best part of the story is the end, where the reader is left to wonder if Emma has gotten involved in a situation way over her head and if she actually makes it out alive.

“Far Beneath Incomplete Constellations” by Alexander Zelenyj is a tale of a much older academic who is sexually obsessed with his Japanese student, a young woman named Michi. The man doesn’t want to be seen with Michi or interact with her in any way other than to have controlling, violent sex with her. He views Michi as an empty shell, existing only to entrance him and provide him pleasure.

I will say that the core idea of this story, of a man isolated from feeling any real emotion even in the face of overwhelming desire and of a woman cruelly isolated from the love and affection she desperately craves, is a good one. That makes it even more of a shame that the idea is utterly buried under the author’s overwrought, often laughable, imagery and descriptions. Here’s an example: “Then, a great thunder roared in his dream, swallowing his peace entirely; smiting them down from their lofty ecstasy with its mighty bellowing, two frenzied fuck animals plummeting earthwards within a resounding dirge of agony.”

I’m not sure I’ve ever encountered a story more desperately in need of editing. To call the author’s word choices “purple prose” is an understatement. This stuff is Technicolor neon. The result is a writing style that is simply exhausting to read.

The last story in the collection is “Lussi Natt” by Andrew Coulthard. Tom has isolated himself in his family’s cabin, located in the Nordic wilderness, hoping the location’s previously soothing effect will help him overcome a severe case of writer’s block.

All the elements of a very scary tale are here; a desolate location shrouded in snow and ice, a writer who may or may not be mentally unbalanced, and plenty of supernatural characters. Unfortunately, the story never seems to pull all the elements together into a cohesive whole. Tom bounces from scary happening to scary happening and I was never sure what one character or set of characters had to do with the others. “Lussi Natt” is another story that would benefit from judicious editing; it runs needlessly long, mainly because the author feels compelled to spell everything out for his reader. For example: “From his nose, he felt the telltale pinching that told him his mucus membranes were freezing. At least twenty-five below, perhaps colder, he reckoned.”

Apparently, unless the freezing membranes are described, the silly reader might not realize twenty-five below zero is dangerously cold. The author also tortures us with numerous word-for-word phone conversations between Tom and his wife, much of which is meaningless banter. There are many ways to convey information to the reader and this is definitely not one of my favorites.

All in all, a story with some genuinely creepy moments, but it misses the mark.

When all is said and done, would I recommend Blind Swimmer? That depends on who you are and what you’re looking for as a reader. If you’re a science fiction or fantasy fan and that’s what you’re hoping to find here, you’ll be disappointed. Much of the fiction in this anthology defies a specific genre category. If you’re a reader open to experimental fiction, which is how I would define most of these stories, you might enjoy the collection. I found a definition for experimental fiction, which reads:

[Experimental fiction] “is fiction that sets up its own rules for itself […] while subverting the conventions according to which readers have understood what constitutes a proper work of literature.”

Fair enough. I applaud anyone willing to try something new, to take a risk. But anyone who engages in experimentation—be they writer, artist, scientist, musician, inventor—must be willing to accept that sometimes experiments fail. Sometimes they fail spectacularly.

In the introduction, editor David Rix, writes: “Creativity is not inevitably about isolation, but most people involved with writing will know the subject one way or another, as we sit quietly in our rooms writing our tales and fancies—maybe to be read by the tempestuous and (we are told) sheeplike public, or maybe not. As so-called slipstream writers—writers on the fringes who, either deliberately or not, have steered away from the ’mainstream’ and recognised genres into more individual areas of exploration—maybe it seems even more close to home.”

There’s a subtle (actually, not so subtle) inference here that the sheeplike public isn’t sophisticated enough to appreciate experimental fiction. As a writer of such fiction, this has to be a very comforting idea, especially if your stories aren’t getting published. But, blaming your audience for not appreciating your sometimes failed writing experiments isn’t just self-indulgence—it borders on self-delusion.

Blind Swimmer, edited by David Rix, Eibonvale Press, August 2010, tpb, 360 pp., £10