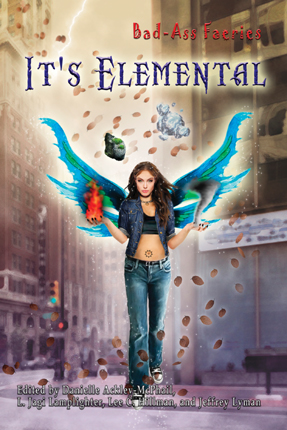

Bad Ass Faeries: It’s Elemental

Bad Ass Faeries: It’s Elemental

Ed. by Danielle Ackley-McPhail, L. Jagi Lamplighter,

Lee C. Hillman, and Jeffrey Lyman

(Dark Quest Books, Kindle -June 2014, Print – Sept. 2014)

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

It’s Elemental, the newest installment of the Bad Ass Faeries series, divides stories into categories by element: earth, air, fire, water, and spirit. Each author presents a different Fae – not a flighty cutsie pixie type, but a more substantial supernatural entity. Few are Fair Folk from European traditions. Urban fantasies dominate the anthology. The pseudo-medieval Europe of traditional high fantasy makes no appearance as a setting. In some of the stories, the time in which the story is set is unimportant, but most include some clue – a toy dinosaur, a mobile home, something – to set the action in a world like the one in which we live. In most cases, the clue puts the story in a modern time. One is set in medieval Japan in the period following European contact, and one seems to be set in Faerie.

Tone varies widely across the pieces, ranging from the lighthearted to the serious. A few seem more to paint a picture than to tell a story. Crafting a story involves lots of parts: the author must present a cause-and-effect world that forces a protagonist to make a character-revealing choice, and requires characters to accept their consequences of decisions – decisions made from motivations the reader can perceive. Writing can be interesting without some of these things – often through humor or mood rather than plot. Plot is interesting mostly because it forces characters into hard choices. Readers can’t tell when a character is tested to the core when faced with opaque characters whose motives and values aren’t known. Readers need these clues: what’s important to the character defines the scenes’ risks, explains the stakes, and frames the climax. But even a piece without classic story structure can entertain with mood, banter, wit, weirdness – anything’s fair game.

But the best pieces in It’s Elemental tell stories. Birts’ breakneck-paced “To Thy Sylph Be True” is a fun tale of a wage-slave screwup redeeming herself in an awful job. Thurston’s “The Face of the Serpent” is a supernatural smackdown with outstanding world-building: the characters duel where the setting and culture perfectly match both the conflict and its resolution. Brown’s “Melia’s Best Wave” is a classic quest, with beautifully built stakes. Through the eyes of a fearful parent, Chambers’ “The Flying Rock” explores coming of age in a world that in every important respect is just like our own. And there’s no reason good stories must have a happy ending. As in King Lear, it’s possible to crush the virtuous and yet succeed. Nye’s “Fifteen Percent” demonstrates this as her mortal protagonist casts off a soul-eating business associate only to crack and take her back because it’s good business. Awful – but delightfully awful.

And that’s what the badass faeries are supposed to be, no?

Kimberly Long-Ewing’s “Spin, Weave, and Measure” depicts a female trio – one spinning, one weaving, and one measuring a final product – who combine some aspects of the Fates with some traits of the Muses. Unlike the Fates, the main characters don’t control mortals’ destinies from their seats: they’ve got to hit the pavement to make things happen. Their values and motives are unclear, though their immediate goal is evident when actively hunting what’s rightfully theirs. As it happens, most of the page count is spent stealing back what’s theirs. The story opens as a fairy heist: rappelling through a skylight, evading laser intrusion detectors, and killing men with thrown knives (which, after the stakes have been clarified, seems in retrospect to be inappropriately dark). Employed for cover in a day job as web (heh) designers, the main characters’ real work seems to involve keeping a piece of innovation-inspiring fairy fabric circulating among mortals. The mortals, naturally, don’t want to give it back when their turn ends, so most of the story’s word count is dedicated to retrieving it at the end of each seven-year loan. When a mortal takes possession of the artifact under an “evergreen” contract that gives the Fae but three days to recover it before the contract renews, the race is on. The resolution shows the main characters back in business after losing a round, which is nice; but without understanding their trio’s grander purpose it’s not possible to understand how good (or bad) that really is. And if losing the fabric to mortals for a while has such little consequence to the main characters, what possessed them to kill a mortal guard in the first scene merely to retrieve it?

L. Jagi Lamplighter sets “On Rocky Ground” in the same world as her Prospero’s Daughter trilogy. “On Rocky Ground” opens on three hikers ascending a mountain in the Italian Alps, bearing what passes among rock spirits for tribute. Two bear it, anyway: one shirks. The other two seem to do all the work on their errand to repay the shirker’s debt. Alas, not all goes well. The lighthearted short follows Mephisto’s absentminded effort to (re)repay a debt while his companions suffer from proximity to all he provokes. It helps to enjoy slapstick humor: if men being crotched in a fight is your thing, or buddies being hit by mistake during attacks on opponents, you’ve found your read. The story makes no pretense at deep themes, but quickly conveys the sense its characters have known (and suffered) each other for a long time; their reaction to Mephisto’s antics feels authentic. The story concludes on a chord made of the notes “I should have known better” and “what on Earth did we do that for?” – perfectly suited to the comic conflict.

Judi Fleming’s “Friends in Dark Places” is a villain-meets-justice story that opens on a teen overnighting under a troll bridge. The protagonist seeks shelter from trouble at home from an abusive drunken step-parent who’s no longer held in check by a now-deceased grandparent. Fleming combines ‘facts’ about fairy-tale reality to build a solution to her main character’s miserable home life: trolls require tribute from bridge users; trolls eat the wicked; trolls seem to be stone in daylight. When the protagonist’s choices escalate his physical danger at home, and he flees over the bridge at night, one quickly anticipates his pursuer’s fate. The fact the resolution seems pre-ordained doesn’t affect the satisfaction it gives: if you like to see thug villains get their just dessert, Fleming wrote this one for you.

“The Flying Rock” by James Chambers opens on a hill overlooking kids’ grandmother’s home, where the children’s father teaches them lets-pretend games. At least, some of them look ‘pretend’ for a while. The story looks at the outset like it might be about the power of children’s innocence or the strength of imagination before kids are taught to believe in their limits. But when the protagonist’s children take flight under the guidance of a Faerie queen, the tale turns dark and serious: what’s flight without the risk of falling? Like fairy tales of old, the story is a metaphor: to raise children to dare great things requires accepting their risk of coming to harm trying. The protagonist’s choice is simple: when the path to success runs directly through the storms of suffering, will he keep his kids from opportunity simply to shield them from risk?

“The Flying Rock” offers a choice that echoes in the real world: the power and freedom to accomplish great things is the power and freedom to wreck one’s life. When fictional notes make chords with reality, the result resonates with a power that goes beyond the action on the page. As Jim Butcher noted in a panel interview on urban fantasy, Mark Twain advised that the proper proportion for fiction was one part invention to two parts fact. “The Flying Rock” is full of facts that make its fiction feel true. Parents can’t protect kids from themselves without crippling their potential for success – yet what protection is that? Chambers’ “The Flying Rock” imbues with supernatural power comments every reader’s heard: parents’ instruction that their kids must ‘stick together’, for example, and the reassurance parents wouldn’t allow a child to attempt what they didn’t believe the child ready to achieve. The force of Chambers’ resolution isn’t so much crafted from the details of the story’s conflict as it is built from truths about life the story reflects. When we age and fall into ruts we forget our important choices; our skeptics surround us; to dare success requires risk; nothing worthwhile is without price. “The Flying Rock” has the virtue central to the best fairy tales: deep down, it’s all true.

Danny Birt’s “To Thy Sylph Be True” opens with a young sylph’s observation that humans – excepting BASE jumpers and their ilk – are mad. Her disdain for most mortals doesn’t improve her customer service when she interacts with humans for work. It’s entirely unsurprising – but fun – to learn the sassy sylph not only has a brother in prison, but is herself on probation after altercations with her boss at her job as a courier for what seems a Fae competitor to FedEx. And “guaranteed on time” has a bit more bite when backed by the courier’s own oath – which Fae must abide. When opposition appears after the clock is ticking, the story begins to feel like a heist’s escape scene, or a fairy-tale version of Smokey and the Bandit. Terribly outclassed by sophisticated opponents – and carrying an over-the-weight-limit package – our protagonist’s outlook gets worse and worse as she nears her destination. But delivering the thing isn’t the worst part of her day. Birt’s “To Thy Sylph Be True” is an exciting adventure that follows a smartass protagonist outmatched while facing stakes that escalate from threats to her livelihood to threats to her life and her brother’s. Birt’s “To Thy Sylph Be True” is a light, fun read.

Peter Prellwitz opens “Stormbringer” near the end of a record-setting Atlantic air crossing: the Fae in business class is on a mission. Prellwitz does solid work building anticipation about the Fae’s purpose in the U.S. at the behest of, or in collaboration with, federal agents. Well-built anticipation acts like an account credit, keeping pages turning even when the story slows for explanation, because the reader accepts that the answer – when it comes – will satisfy. Before the antagonist appears, the aloof Fae at the center of the action dismisses mortals she doesn’t view as warriors – from border functionaries to law enforcement officers offering ordinary politeness. She dresses down two would-be pickup artists – one verbally, which seems appropriate, but one with direct physical violence punctuated with the threat of torture and death. Before her geriatric-looking barkeep son reveals who she’s in the U.S. to battle, the two hold an exposition-heavy conversation to inform readers how the world works and who the players are. By the time the Fae learns she’s in town to battle a daeva (and if she’s a high-ranking Fae, why doesn’t she know why she’s traveling and over what she’ll risk her life?), much of the cool-supernatural-doings credit “Stormbringer” built in early pages has been expended buying reader tolerance for an unlikeable protagonist. We never learn why a Fae from Europe repeatedly saddles up with Americans to battle the United States’ enemies, or why her barkeep son knows the identity of a target so secret even part of the strike team is unaware the target is supernatural.

Alas, “Stormbringer” reveals only one motivation for its Fae warrior: zeal for battle. This does nothing to explain why she’s in the U.S. in particular, or why she flew A-10s in the first Gulf War. When we learn she has no fear of death – she’s visited Valhalla, has friends there, and likes it – what are we to believe’s at stake? She rates battle above time spent catching up with loved ones she’s not seen for years; though plainly the main character, she feels more like a weapon than a protagonist. Warring because it’s glorious might elicit some interest, but it doesn’t explain the world around the main character, and makes a difficult nest in which to hatch sympathy. Since “Stormbringer” doesn’t describe the villains’ villainous villainy, sympathy for protagonists can’t erupt from an enemy scheme that’s too awful not to hate. Why are these guys worse than other weapons smugglers? Why would this Fae care? If she’s really a top warrior, why’s she being risked on this? She may be too eager for blood to care, but surely whoever picked her target should know. Why are mortals picking a Fae warrior’s targets? When she starts fighting with her axes, does she do it just to be sporting before finally obliterating the daeva with her never-before-hinted-at sunlight-in-the-darkness superpower? Who knows. If “Stormbringer”’s protagonist were more sympathetic, it might be more tempting to find out.

DL Thurston’s “The Face of the Serpent” is a high-concept story that quickly builds a unique Fae confrontation by leveraging the culture and traditions of the colorful Mexican professional wrestling known as lucha libre. In lucha libre, the participant luchadores are distinguished by colorful masks unique to their in-ring personas. Unmasking a luchador has symbolic impact in the lucha libre subculture, and occurs when the luchador ceases competing with the mask – such as when losing a match in which the stakes require the loser to give up his mask, or at a fighter’s ultimate retirement. The title thus immediately tells us the luchador’s mask – and his career as The Serpent – is at stake. But that’s not the story’s true genius. As soon as Thurston reveals his protagonist as a supernatural luchador, it is immediately obvious that Fae professional wrestlers and down-on-their-luck old gods looking for mortal attention have just got to try lucha libre. Thurston’s high concept supernatural pro-wrestling smackdown is reason enough to cheer, even if it had nothing else going for it.

But, wait! It gets better. “The Face of the Serpent” opens with a pre-match locker room preparation scene that evokes everything we know about Boxer Puts On His Gloves One Last Time stories. The old boxer image combines with the impression of a weakened supernatural snake-spirit reduced to pro wrestling to draw worshippers, creating a sympathetic and internally consistent protagonist who’s easy to get behind. I mean, you liked Rocky didn’t you? The not-young-any-more fighter is classic. And Thurston’s setup connects the lucha libre tradition of representing personas with masks to old religions’ use of ceremonial masks. It’s a powerful, fast story setup – a work of art in itself. When departed Aztec gods begins giving The Serpent grief over his chosen line of work, we see the true shape of the story’s conflict. “The Face of the Serpent” invokes the imagery and tropes of lucha libre to paint conflict, victory, defeat, and rebirth in a setting beautifully suited to a wanted supernatural entity living incognito despite requiring fame and adoration to thrive. The characters and their conflict appear in a world masterfully designed to meet their supernatural needs, and the resolution is a beautiful solution perfectly suited to the lucha libre world in which the story is set.

James Daniel Ross’ “The Legend of Buck Cooper and the Child of Fire” is set in an alternate New York after the Civil War. Early background paragraphs tantalize a New York in which unseelie gangs menace mortals in dark alleys. The narrator turns out to be a protagonist: ultimately, he willingly undertakes the quest to save a(n inhuman) child, and when the child’s supernatural family grants him a wish he foregoes traditional treasures to wish Fae forever barred from the mortal world. But it’s a long road to the heroic choice. Most of the page count involves the narrator tagging along behind the titular Buck Cooper, who lands the narrator a job in a fire brigade. Since we don’t know what the characters’ values or motivations are up front, it’s hard to tell whether to be happy or sad about the facts related by the narrator. The characters seem to have nothing at stake until they endanger themselves as firefighters, and that danger feels purely physical. Since we can’t tell when the characters are winning and losing, the discovery that a child rescued from a fire is an efreet has little meaning. Does this help the characters? Does it harm them?

“The Legend of Buck Cooper and the Child of Fire” later provides clues about the characters’ values and choices through a talking-head infodump, but it’s hard to appreciate what’s going on during a first read. The ineffectual fire chief seems without depth. The police sergeant who directs the narrator to find Cooper when he goes missing with the young efreet seems to have no purpose but to infodump while gifting the narrator with a .32 Colt. Why? We never learn. When Fae finally appear, why should post-Civil War goblins sound like bad German movie villains? It takes so long to learn about Cooper’s altruistic compulsion to rescue strangers’ children that we don’t really appreciate it when he first advances his purpose. Once it’s fully explained, we still don’t understand it: losing one’s own family drives men as easily to drink, or to re-marry. What really makes the title character tick? A mystery.

Without insight into Cooper’s internal dialogue, we can’t tell whether his daredevil behavior is undertaken with knowledge of the risks, or in conscious defiance of them. Toward the end of Cooper’s action we finally see the narrator as Cooper’s foil – illustrating Cooper’s success rehabilitating lost youths, and forcing Cooper to articulate his unwillingness to abandon the young efreet. When Cooper charges the narrator with completing his last rescue, readers are treated to an emotion-evoking final stand, the description of which is artfully short. But the narrator’s own escape takes pages and pages, in which he shoots adversaries with the gift .32 and slits their throats with an athame lent him (for some reason) by a local witch he just met. It’d be much more satisfying to feel the action resulted from character decisions that are driven by motives readers could know and appreciate. Characters who react without a comprehensible plan to an inexplicable world full of surprise gifts do not convey much sense of story. I suppose it’s nice New York isn’t overrun with goblin gangs any more, but do the details mean anything? If not, why would they hold attention?

James R. Stratton sets “The Ties That Bind” in Japan before the age of gunpowder. The tale begins with a classic ploy: clever mortals outthink a powerful supernatural opponent. This part feels well done, and creates good anticipation about the Tengu driven to fulfill his bargains and redeem his offended honor. Unfortunately, the momentum falters setting up and depicting the battle in which former enemies build mutual respect fighting a common foe. When James Clavell leveraged Japanese values to set the stakes in Shōgun, he spent time illustrating how each character personally sacrificed for the values and believed in them. Until each character’s personal values had been illustrated, the stakes could not be shown. So when “The Ties That Bind” plunge characters into battle with no idea why the enemy matters to the individuals, or what dreams they chase in the conflict, we’re unaware what’s at stake beyond the Tengu’s obligation to make good on a bet. It’s much more interesting once the purple-skinned Tengu is investigated by a fox-spirit from his master’s court, and he fears she’ll learn he’s lost custody of his lord’s favorite pet in a bet. Not only does his internal dialogue make clear he fears discovery, but the gravity of embarrassment – and the threat to his status in the community in which he lives and works – make an easily understood motivating force. Alas, the Tengu need not demonstrate cleverness to preserve his social station and his life: he’s rescued by a new ally.

“The Ties That Bind” reveals little about characters’ motivations beyond their desire to demonstrate traditional Japanese feudal virtues like loyalty and sacrifice; none of their choices appear to involve personal conflict. Willingness to do battle, willingness to protect one’s lord’s allies, and willingness to train at arms all seem easy choices given the revealed motivations. Without a hard choice to confront characters, how will we learn what they’re made of? The resolution – that the mortal warlord’s daughter befriends a powerful supernatural warrior willing to instruct her at arms – certainly looks like a happy ending for all involved. Since the Tengu’s service isn’t done, it’s not evident he’s redeemed himself after his errors at the story’s open. And since the scheme to provoke the Tengu into risking himself wasn’t the daughter’s idea but her father’s, the resolution doesn’t feel like it closes a plot arc on a story about a clever mortal: it feels like all the characters get a gift. I conclude the story is intended to depict the triumph that comes to the virtuous, and feel the tale would benefit from more world-building around the crucial, tested virtues.

The narrator of Patrick Thomas’ “Looking a Gift Horse” initially complains about being smacked in the face by branches, flying through a forest fifty feet from the ground. It’s surprising then to discover her real conflict involves slavers, sexual assault, and her mother’s recent murder. The narrator’s light tone feels so inconsistent with the dark, traumatic adversity she describes that the message is difficult to reconcile with its medium. Readers sensitive to sexual assault as a plot device, or its threat as a motivator, may wish to be alerted to these elements before beginning.

“Looking a Gift Horse” has a flying narrator – seemingly proof she’s Fae – but she refers to herself both as an eleven-year-old girl and as “Terrorbelle”. Her curses don’t have the feel of an eleven-year-old (“Ckuf”?). Nonstop emergencies substitute for a description of the values and motives needed to understand why she fails to avenge her mother when she has no opposition. Other mysteries generate confusion, and motivate re-reading for missing details: why is a flying narrator worried about pursuers afoot? We never learn who her enemies are, who raped and murdered her ogre mother. The main description – that they are slavers wearing gray coats – does little to aid understanding what their powers are. Or, for that matter, their motivations: we just see their classic villain conduct. When the adversaries fight, they seem to use iron weapons: are they mortals? It’s hard to picture the conflict, or imagine why a flying narrator is at risk from a foe afoot with a sword. When we learn the narrator hunted her pursuers following her escape from slavers, but struggles with lessons from her mother about violence, we’re left confused about her values and motivations – things the reader would expect to see clearly in a first-person narrative. Although the piece appears to promise a protagonist who’s not a stone-cold killer, the resolution simply re-equips her to begin hunting her enemies again. Attacking enemies by stealth has apparently always been in her repertoire, though; it’s how she got to her position at the story’s open. What decision has she made that changes who she is? By confining description to the physical world, the emotional impact of the narrator’s experience is muted just as her presumed internal change is concealed. The story feels much stronger when the narrator bargains with a water-fae to murder her pursuer, but the piece never illuminates who the narrator is inside, what she values, and what really motivates her actions. As a consequence it’s hard to understand the meaning of the physical conflicts described, and difficult to appreciate what if anything is resolved in the conclusion.

NR Brown opens “Melia’s Best Wave” on a novice surfer just standing on his board for the first time while the protagonist nudges the waves just so, to ensure his success in his first foray into surfing: water sprites, as it turns out, thrive on wave-worshippers. Though structured as a quest, “Melia’s Best Wave” is a sort of environmental romance: though it suggests mortals should look after the beach better, it posits that the diligent Oceanid looks out for beach-lovers in return. Soon, Brown’s sketched a water-sprite pecking order, in which Oceanids compete to oversee beachfront territories around the world. It’s in that endless supernatural tournament that the eponymous protagonist has made her career: she’s a badass. But her protective bent makes her a friendly badass. And not reckless, either: she’s thoughtful and exercises caution rather than risk herself senselessly reacting without a plan. She’s a thinker; she surveils Mavericks when it draws her interest, before revealing her arrival and making a bid to oust its incumbent Oceanid. So it’s fun when onlookers yell to the kook about to get killed making a mistake surfing Mavericks, and it dawns on the protagonist that “she was the kook.” The offense she takes at her kinsman’s neglect of Mavericks reflects her mortal friend’s offense at mankind’s pollution of the near-shore waters. Brown does a solid job of making Melia’s quest not just about her own career, but a matter with a credible moral dimension.

Much as Emma Bull’s rock-themed novel War for the Oaks decides the fate of Minneapolis through a contest that has a battle-of-the-bands vibe, the surfing short “Melia’s Best Wave” climaxes in a duel whose physical manifestation looks like a surfing competition whose nominal stakes include dominion over Mavericks. Brown escalates the stakes to include not only dominion over Mavericks, and the protagonist’s career, but her mortal friend’s life. It’s a fun ride.

Bethany Herron’s “Fairyland Local #2413” opens on a lonely, tired railway control point operator with aspirations of finding more exciting work, if his injured leg ever healed. After depicting the railman’s boredom and his hope to return to less lonely work, the story launches into a railway emergency later revealed as the work of a bored Fae. Although the story implies potential peril to the railway operator’s work (nobody else saw indications of faults during the emergency, raising the question whether he’s a screw-up unfit for work), and he ends up owing the Fae a debt after teaching him to play cards, he’s never seemingly put in real peril. Rather, he is befriended by prankster Fae who’ve learned to ride the rails without tickets. By the end, “Fairyland Local #2413” has a light tone that feels like a fun voice in which to read about Fae pranksters – but none of the characters seem to demonstrate a completed character arc. The rescue of the pregnant co-worker doesn’t require the main character to change, and while it’s difficult it places none of his values at stake; its main effect is to illustrate that his Fae acquaintance can do good deeds for those from whom he wants something. It’s pleasant to see the main character’s misery working solo in a control point finally alleviated by the promise of a steady stream of Fae travelers, but a pleasant tone and some promising characters don’t by themselves make a whole story.

In Jody Lynn Nye’s “Fifteen Percent” the main mortal character is a bestelling author whose Fae literary agent and muse takes fifteen percent – not of book income, but everything. When she berates him for ‘leaving’ her ‘to go hungry’ she’s not talking about her need for her cut of his paycheck. She has other needs. The protagonist doesn’t begrudge his agent her pay, but he grates at the loss of fifteen percent of his creative energy – ideas lost forever, work the public will never see, quality he fears represents the very best of his potential. And that’s the story’s big idea: it’s a horror story of financial success at the cost of work quality – at the price of his soul. But it’s also comic: when energy-draining Fae scuffle over the right to feed on the protagonist, the sniping is anything but Fae. The theme is plainly the sacrifices made for art. The dark resolution is well suited to the setting. The heroic choice to suffer and work in freedom and not to sacrifice one’s soul for outward success just doesn’t pan out. Funny. Delicious.

Keith R. A. DeCandido’s “Undine the Boardwalk” is a reprint from his collection Ragnarok and Roll: Tales of Cassie Zukav, Weirdness Magnet (Plus One Press, 2013).

Lee C. Hillman’s “Bad Blood” opens in colonial Massachusetts on an indentured servant with three months left to work off her debt. Almost as soon as she thinks how little time is left before she can join her beloved, she receives a banshee-delivered notice of his death at the hands of another man. Little wonder, then, that the protagonist has such little fondness for the work when she becomes a banshee herself: when the time period skips near the present, the protagonist’s giving out death notices of her own. Informing women the man they love has been killed by another man isn’t glamorous. Banshees don’t celebrate the deaths, but are bound ’til they retire to herald men’s untimely deaths at the hands of other men, by informing some clanswoman who outlives them. The protagonist hates the gig: she doesn’t just want to quit, she wants to put banshees out of business. Since she’s noticed banshees aren’t obliged to announce deaths that aren’t caused by men, her cure looks a lot like the disease. She initially targets violent thugs she’s sure will soon die by the hand of some man. But her grisly solution doesn’t work the way she hopes. Enlisting women to control their lovers doesn’t pan out, either. The resolution doesn’t offer reason for optimism. The protagonist’s climactic choice isn’t some disaster-resolving trick, but surrender to the conviction she can’t change the world about her. It’s not a traditional protagonist resolution, but it suits a dark tale about a problem as intractable as mortal conflict.

The Bad Ass Faeries volume It’s Elemental contains happy endings and frightful ones, Fae protagonists and Fae villains. If you love faeries, you’ll find in it stories you won’t want to miss.