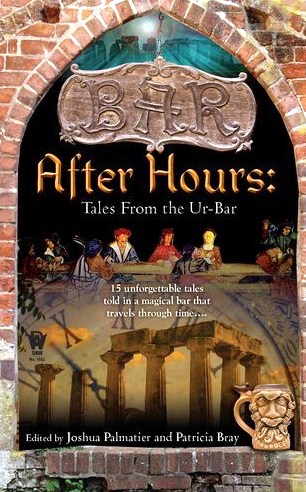

After Hours: Tales from the Ur-Bar

After Hours: Tales from the Ur-Bar

Edited by Joshua Palmatier and Patricia Bray

(DAW, March 2011)

“An Alewife in Kish” by Benjamin Tate

“Why The Vikings Had No Bars” by S.C. Butler

“The Emperor’s New God” by Jennifer Dunne

“The Tale That Wagged The Dog” by Barbara Ashford

“The Fortune-Teller Makes Her Will” by Kari Sperring

“Sake and Other Spirits” by Maria V. Snyder

“The Tavern Fire” by D.B. Jackson

“Last Call” by Patricia Bray

“The Alchemy of Alcohol” by Seanan McGuire

“The Grand Tour” by Juliet E. McKenna

“Paris 24” by Laura Anne Gilman

“Steady Hands And A Heart of Oak by Ian Tregillis

“Forbidden” by Avery Shade

“Where We Are Is Hell” by Jackie Kessler

“Idzu-Bar” by Anton Strout

Reviewed by Carole Ann Moleti

So, seven authors walked into a bar, each with a story weighing heavy on their minds. According to the editor’s note, the smooth, eminently readable, highly enjoyable result of co-mingled spirits—writerly and distilled—was After Hours: Tales from the Ur Bar.

The anthology, edited with a light touch by Joshua Palmatier and Patricia Bray, consists of fifteen short pieces, all of which are on the longer side. The unifying theme is the link to the mythological Gilgamesh. Gil, who is known throughout by several different names, depending upon the century and part of the world the portal of his magical bar happens to open up in, is the ultimate bartender, serving up potions to fix whatever magical affliction ails the patrons, along with the sage advice of one who has been around an awful long time, and for whom there are no new stories.

Benjamin Tate’s “An Alewife in Kish” begins the pub crawl, introducing us to Kubaba, imprisoned by the gods and doomed to spend the rest of her life serving beer to foul smelling travelers.

“Then, pitcher full again, she straightened—And caught sight of the tablet resting on the shelf of the niche behind the urns of beer. The gods had placed it there to mock her, Ninkasi herself inscribing the recipe for beer upon it before setting it upon the shelf and vanishing with a final laugh, the last lines of power—of the god’s punishment—settling around Kubaba and the alehouse like a weighted fishing net.”

That tablet makes a cameo in each succeeding story, and at the end the alewife manages to trick Gilgamesh and escape by offering him immortality, thus setting him up as the new proprietor.

“I’ve left you the vial and the tablet. You have everything you need. The alehouse will provide the rest.”

“Why the Vikings Had No Bars” by S.C. Butler then takes a heartbreaking turn as two young men fulfill the legend that Sons of Odin turn into bears when they fight. The stakes escalate with each round as the men vie to outdo each other while indulging in wine, ale, and virile fantasies all the way to Valhalla

“It will never work,” he declared.

The proprietor ignored him, continuing to wipe the table. Like most of his type, he was stoic, but not bright. “What will never work?” he asked.

The old man swept his staff at the longhouse behind him. “You can’t run a public alehouse in Daneland.”

The proprietor shrugged. “I have worked rougher towns.”

The old man shrugged.[…] It might be good for my people to learn there’s more to life than blood and beer.”

It takes a strong man to deal with a bar full of Viking warriors, but Gisl is up to the task, along with some help from the Valkyries.

The time machine takes us, along with Otto, ostensibly to conduct secret negotiations between the Holy Roman Emperor and The Republic of Venice. But only Peter’s most trusted aide, John the Deacon, knows Otto’s true identity.

“The Emperor’s New God,” by Jennifer Dunne, is set in the perfect backdrop for intrigue, amidst the misty streets and canals of the ancient city, with the assigned meeting place, a tavern, which was “the only place in the world where man and gods still mingled.”

Otto is about to meet Mars, and who better to preside than the barkeep who was “clearly a man with no softening, so he wasn’t Bacchus. He showed no signs of Priapus’ eternal erection. Was he perhaps Liber? But no, Liber was the height of a normal man.”

And indeed, Otto must decide how to conquer Rome before Mars finishes his glass of Ambrosia, in this place where time slows to a pace more suitable for those who have all the time they want.

Otto makes a fateful decision, and must bear the consequences, he a man of scholarly pursuits rather than a warrior, negotiated with the wrong deity. Will he get a second chance?

Barbara Ashford’s “The Tale That Wagged the Dog” is much less Machiavellian and much more humorous. A selkie and a talking dog join the “usual mix of dead heroes, enchanted folk and curious locals” who all desire some of Gil’s magic elixir to provide them with something they don’t have.

The Selkie goes forth to seek her skin, misplaced in a moment of passionate abandon with Tam, who the Queen of Faery transformed into a Border Collie. The doggie has his mind on one of his body parts as well, to the exclusion of anything else.

Gil can’t leave his establishment, but they can and do, continuing their search until Tam returns desperate, bereft, that no matter how strong the potion that Gil serves up “becoming a man takes longer for some than for others, and that every man is a bit of a dog.”

Ms. Ashford’s use of personification is spot on. Raunchy, bawdy, hysterical.

In “Sake and Other Spirits” by Maria V. Snyder, Gilga-san tries to protect Azami, recognizing the beautiful serving girl has something special inside her in addition to a jilted Samurai on her tail. She fears the Kappa haunting the lake, but the return to her betrothed much more. The symbolism in this story mirrors that employed by Eugie Foster and Aliette de Bodard elsewhere, and shows the more tender, righteous side of Gilgamesh.

As dark as the previous tale is light, “The Fortune-Teller Makes her Will” by Kari Sperring exposes the seamy lives of Parisian aristocracy, outside the “gilded precincts of Versailles, where the king had no love for such creatures, who he regarded as charlatans at best […] soothsayers […] in their Parisian lairs.” Gil’s potion does the righteous thing in this story about the metaphysical, magic, and the misuse of children.

The historical note at the end of “The Tavern Fire” by D. B. Jackson provides this explanation:

“Early in the morning on March 20, 1760, a fire started at Boston’s Brazen Head Tavern, which was owned by Mary Jackson. […] the fire consumed forty-nine buildings and homes, left more than one thousand people homeless. […] No one was killed. To this day, the cause of the fire is unknown.”

Tiller, the simple minded panhandler couldn’t understand what mean spirited Mary Jackson wanted his friend, the kindly Negro bar maid Janna, to do. But he did know enough that he’d gotten Janna in trouble by telling others she could perform magic.

Even when offered more money than Tiller could fathom, Janna refuses to cast a love spell, but he knows she is in trouble. Gil, a defender of innocents, gives Mary what she wants. He “merely granted her wish, the rest she brought to the casting herself.”

The mood turns Gothic with “Last Call” by Patricia Bray. George Harker had a lot to live up to as the younger brother of Archibald; the greatest hunter the Order of Sidon. Haunted by the memory of his first kills, a lamia that sounds more like a vampiress and her victim, George never felt he was quite up to the honor of assuming the helm of the knights whose painstaking rituals, passed down from the first knights, destroyed monsters that men of science had not yet learned to recognize, let alone control.

But he survived the others, proving he was up to the task. The potion provided George’s last call—release from the unnaturally long life that cursed both of them—a state Guillaume by this time had learned to abhor.

“Alchemy of Alcohol” by Seanan McGuire lightens the dark mood a bit, with the exploits of wacky bartender in Gils’ establishment who’d learned the delicate art of maintaining the proper lighting for a drinking establishment to:

“…balance mystery with secrecy, true class with shabby gentility and, most of all, obscurity with discretion. […] windows covered with a carefully maintained mixture of dust, soot and coal powder, the gas is never opened past a certain mark, and there are no electric lights outside the living spaces above and the workroom below […] the lights will stay low, the windows will stay opaque, and the house whiskey will stay cheap.”

Mina Morton was tending bar while Gil got some sleep upstairs when the guy carrying the corpse came in and glass started breaking along with the carefully crafted mood.

Mina’s basement, full of potions, was secured to withstand another big one in San Francisco. As such, it was perfectly adequate to concoct “midnight” to awaken the Winter Queen and contain a battle for supernatural dominion between her, the sister, determined to steal her place, and the brother-in-law trying to unseat the Summer King.

Gil made a good choice hiring Mina, who understands that mixing a good potion is a lot like mixing a drink. “Both require a steady hand, a firm understanding of the ingredients, and good idea of the desired result.”

A most enjoyable story with an unflappable, if somewhat batty heroine and a drink recipe for readers to try at home.

The next three consecutive stories continue the foray forward into the twentieth century. Set just before World War II on the road to Vienna, “The Grand Tour” by Juliet E. McKenna chronicles a sightseeing trip turned ugly when two Brits come under attack by German toughs as the tension between the two countries escalates. Save for the injured men’s proximity to Gil’s bar, and one of his healing potions, there would have been two fewer grateful men to help heal war torn Germany.

“Paris 24” by Laura Anne Gilman chronicles a night out for the Olympic fencing team who happen upon Gil’s, an atypical establishment in Paris, but one which teaches an ambitious team member a lesson about life.

“Like any good bartender Gil could read his patrons. Over the millennia he had been trapped within the confines of this bar, he had honed this skill until it was almost uncanny, knowing what they desired, what they feared, what they needed. Most of the time it was merely a pause: for refreshment, for drowning their sorrows or speaking them, but before they went back out into the world. […] Sometimes, not often, they needed more. Sometimes they had learned more, merely by being more than their fellows, having some spark of fire their fellows lacked, banked or slow-burning, waiting only the gift to make it bloom into open flame. Were one of these three such a man?”

Richard thinks he knows what he wants: the honor, the glory, the fame of winning an Olympic medal, of fighting and winning the next great war.

“Knowing what you want,” the bartender said, speaking, it seemed, only to Richard, his shagged-curled head leaning in close, his voice pitched to carry through the endless murmur of noise. “Being very sure of what you want. C’est ce qui compte. That’s the trick.”

Richard takes his advice and goes home happy, even if it wasn’t what he thought he wanted. This story was well placed, affording the reader a moment to recall what Gil has been up to, and what challenges he faces.

The most compelling of the stories in this anthology come toward the end, and Ian Tregillis’ “Sturdy Hands and a Heart of Oak” is one. Reggie Brooks, a sapper in London during World War II, uses his gift of sight to defuse undetonated ordnance dropped by the Germans before they exploded, then goes about his business of womanizing and breaking hearts.

Reggie can feel, sense, what’s ticking inside the bombs, because he’s had a lot of practice seducing and undressing women. While celebrating his last job at the Sword and Bull, as Gil’s establishment is known in those parts and, after a shot of Gil’s special, his sight broadens and Reggie makes the first unselfish decision of his life.

Mr. Tregillis’ protagonist is unlikable but, by the end, the elixir he concocts magically transforms Reggie into a hero. The choice of first person was bloody brilliant. Honestly, one of the best stories I’ve read in a long time.

“Forbidden” by Avery Shade adds a bit of science fiction to the fantasy. G5S36 is known as Rebecca in the 20th Century, but Geneticist number five in sector thirty-six. An Everyman. Her mission: to bring back some DNA to mix up and refresh the gene pool.

Gil warns her away from “the player.” Mr. Tall and Handsome, a “conscienceless disease in the fabric of the 20th Century. She considers obtaining her sample from him, but sends him away, soothing her strange sense of regret with one of Gil’s clear elixirs.

“Sure, Why not? If I’m not going to experience what real copulation is like tonight, I can at least go out on a limb and experience an alcohol high.”

Rebecca is torn between what she, as an Everyman, should do and what she wants to do. The clear, not so sweet drink Gil prepares isn’t decadent enough to make her feel criminal, and actually clears her vision, illuminating the path she must take.

This very clever story parlays the excesses of New York City in the 1980s, when greed and yellow ties ruled the markets, before AIDS transformed casual sex into a deadly game of Russian roulette. It’s a chilling commentary of what the future might be like if we go too far in the opposite direction.

“Where We Are Is Hell,” by Jackie Kessler is the second in this anthology that grabbed me by the throat and didn’t stop squeezing, even after it ended. Gil sees the “little ghost” enter the bar after she’s wandered for an eternity seeking a door that will actually open.

Gil offers her the opportunity to take his place, to stay semi alive in the tavern rather than go back into the Endless Caverns so he can finally leave. But he doesn’t trick her like the Alewife of Kish did to him.

“Take over my duties,” says Gil, “and you never need to worry about doors again. Tracy knows there’s more he’s not telling her […] but, even so, the offer is compelling.

But she declines and Gil gives her drink, on the house since she has no money, to see her off.

“One more door, Tracy Summers, and then you’ll finally arrive at your destination.”

Even told in third person, Tracy’s intense confusion, disconnection, guilt, and resignation seeped inside me. Her sense of sadness that death, particularly one as unexpected as hers, leaves no hope of reconnection to anyone you’ve ever loved—even to simply say goodbye, is palpable.

It seemed to me like this should have been the last story in the anthology, completing Gil’s character arc. Perhaps that is why “Izdu-Bar” by Anton Strout didn’t wow me. Or maybe it’s because Bouncer Billy is such a miserable character not even Gil’s magic can transform him. It might also be that Gil spends so little time on stage, allowing the bad boy charged with keeping the Zombies outside in the Waste to take liberties Gil likely wouldn’t have condoned.

The magic, which turned equally flawed and bereft characters into heroes and heroines in Mr. Tregillis’ and Ms. Kessler’s stories is the missing ingredient in Mr. Strout’s brew: the hint that there is some hope, something better to come, some cosmic justice. After all, isn’t that why folks commiserate in their local Ur-Bar?

This time travelogue of fantastical tales born of myth and steeped with legend and lore is a leisurely, accessible read. Editors Joshua Palmatier and Patricia Bray have put together a unified anthology of tales while preserving the unique voice and writing style of the individual contributors. Entertaining, thought provoking, and fun.