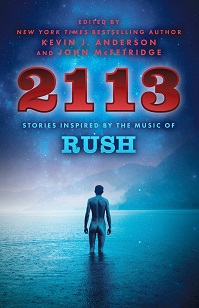

2113: Stories Inspired by the Music of Rush

2113: Stories Inspired by the Music of Rush

edited by

Kevin J. Anderson & John McFetridge

(ECW Press, April 2016)

Reviewed by Brandon Nolta

Rush and speculative fiction go together like space opera and ray guns. From almost the beginning of their 40+ year career, the Canadian rock trio have never been shy about their influences, writing and performing songs—and now and then, entire albums—with roots in fantasy and science fiction, with lyrics inspired by Coleridge, Ayn Rand, Tolkien, and many others. Under the auspices of editors Kevin J. Anderson and John McFetridge, a collection of contemporary authors has returned the favor with the anthology 2113. Like Rush itself, the stories are all highly professional and technically proficient, and like Rush’s music, certain themes repeat throughout, and the collection as a whole won’t be to everyone’s taste. However, it’s an impoverished soul who can’t find at least one thing of value in the collected work of Lee, Lifeson, and Peart (full disclosure, I am a Rush fan myself), and likewise, the range and breadth of stories here offer a striking array of riches for fans to peruse.

To start the festivities, Greg Van Eekhout tells the story of two teenage friends, Deni and Sherman, in “On the Fringes of the Fractal,” a less-than-subtle homage to “Subdivisions.” All the world’s a suburb in Deni and Sherman’s world, where jobs, entertainment, and even voting rights depend on “stat,” a calculation based on how attractive one is, how up-to-date their fashions are, how much money one has, and so on. Through a perfect storm of bad luck, Sherman and his family lose their stat, and in an effort to help him, Deni takes Sherman on a long road trip that involves a talking dog, a city being made anew, and learning to live in the walls and hidden spaces, stains on society’s perfect fractal patterns. Van Eekhout captures the plastic fantastic nature of the world with calm and eerie precision, but the story doesn’t develop the basic concept much beyond what the lyrics of the original song did, and the one-joke nature of the story falls flat at the end.

There’s a little more inspiration to be had in Ron Collins’ “A Patch of Blue,” which follows the twin narratives of Galen, a designer of simulacrum universes in dimensional folds, and Ishi and Alex, two musicians in a commercially popular but artistically empty band residing in one of Galen’s models. All three characters are trapped in their lives, though Galen seems happy enough, but when Ishi and Alex find a way to escape their lives—and find their way into Galen’s world, if briefly—they open a door for Galen to escape as well. While the narrative could stand a little more development, as the Ishi and Alex story feels a little rushed in comparison to Galen’s, the intriguing narrative hook and Collins’ lovely writing make the story a satisfying read.

Brian Hodge’s “The Burning Times v2.0” is another example where the story follows the original musical inspiration—“Witch Hunt,” in this case—very closely, perhaps to its detriment. This tale of a teenage boy, one of the few males to possess a talent for witchcraft in a future essentially ruled by book- and art-burning hooligans, and how he discovers the true nature of his power and what he can do gets right to its point efficiently and cleanly, but offers no surprises or wrinkles of interest. It does what is intended, no more.

On the other hand, Michael Z. Williamson puts together a pair of songs for inspiration and comes up with “The Digital Kid,” one of the anthology’s unqualified successes. Williamson’s tale follows Kent, a young man with dreams of the stars, as he progresses toward his goal, only to have it torn from his grasp by a horrific accident that leaves him with a traumatic brain injury. Slowly, Kent heals and learns to live with what he’s lost, and over time, Kent finds a way to pursue his dreams again. With a marvelous control of tone and measured prose that captures the emotional rises and falls of Kent’s life, Williamson gives readers a stubborn, human hero to root for, and brings all the pieces together for an ending that feels triumphant and, better yet, fully earned.

Inspiration is a two-way street, as “A Nice Morning Drive” by Richard S. Foster illustrates. Originally running in the November 1973 issue of Road & Track, the tale of Buzz, a man who chooses to keep driving his MGB roadster despite the ever-present threat of larger and larger cars made impervious by modern safety features, was the stimulus behind “Red Barchetta.” In reading the story now, more than 40 years after its publication, Foster’s slight narrative feels more like a barely controlled screed against strangling all the joy out of driving a powerful machine, wind in one’s hair, with rules and bureaucratic “improvements.” Still, the story progresses quickly and nimbly, and automotive enthusiasts may find fascination in Foster’s view of the future, and how right he was in some instances.

One of the few tales in the anthology where the connection between the song and the resulting story isn’t immediately obvious, “Players” by David Farland also happens to be one of the few stories with virtually no speculative elements. Solomon Isaac, Hollywood producer and dealmaker, heads to the Middle East to meet with Prince Farhan, a Saudi royal with a love of American films and plenty of money to invest. However, deals bring their own stress, and being a Jewish man in an area of the world that isn’t always welcoming to Jews doesn’t do much for Solomon’s nerves. Surrounded by generations-deep enmity and negotiating with players far more adept than he’d suspected, Solomon must rely on quick wits and his study of neurolinguistic programming to get himself out of Dubai in one piece. Farland’s tale is rich with concrete sensory detail and Solomon’s voluminous inner life, which marinates in a roiling stew of acumen, paranoia, and occasional flashes of suppressed fury, and ends with a uniquely American take on karma; it easily stands beside Williamson’s “The Digital Kid” as one of the standouts of the anthology.

In “Some Are Born to Save the World,” Mark Leslie introduces readers to White Vector, former superhero and current broken man. After years of doing good with his supernatural ability to draw energy from others and redirect it, his brain is pushed to its limit, and an embarrassing incident soon after a massive stroke causes White Vector to hang up his tights. Now slowly dying in a hospital, Bryan regrets the years of enforced loneliness, the feeling that he could have done more, but an encounter that saves his life forces Bryan to rethink his woes and possibly find a measure of redemption before he dies. Leslie explores Bryan’s motivations and fears with a sure hand, and delineates the qualities, good and bad, that could drive a person to dress up and fight crime. Even in the last days of his decline, Bryan is able to rediscover a new purpose and a return of his dignity, and it’s a measure of Leslie’s skill that this change happens in a realistic, yet meaningful fashion.

Not all the stories in this anthology come off quite as triumphant, as John McFetridge demonstrates with “Random Access Memory.” Marcus McKenzie works as an eraser of memories, often working under government contract to pinpoint and delete the offense-related memories of serial killers and other criminals. Other than the frequent subject matter of his work, his life is a straightforward and pleasant one, but memory, as Marcus knows from his work, can be a tricky thing. Unfortunately for Marcus, he may soon discover this first-hand. With a deft control of tone and background info, McFetridge slowly transforms what starts as an interesting, if relatively benign, workplace story into something darker and edgier. The story raises more questions than it answers, but entertains to the very end.

Luis Bergandi, the famous yet obsolete auto racer in Larry Dixon’s tale “Almost Human,” faces a different issue with regard to technology: It’s put him out of a job. Driven by an ever-increasing need for safety and cutting-edge engineering, auto racing is now a sport of machines controlling machines; humans simply can’t compete in precision or reaction time, and the sport is dying. Bergandi respects technology, but knows that the human factor is what makes a race exciting: stakes, mistakes, imprecision, and the art of the miraculous, and Bergandi has a plan to bring all that back. At first blush, Dixon’s story reads like a technical manual for advanced racing technology, but as the story edges closer to Bergandi’s big reveal, the humanity and joy Bergandi and his colleagues feel when racing bleeds through. It’s the heart behind the machine that matters, a truth that Dixon illustrates with grace and feeling.

Most of the stories in 2113 take place in some variant of the future, but Tim Lasiuta reaches back a few decades with “Hollywood Dreams of Death,” which relates the storied career and terrible downfall of Lazlo Delorean, leading man, ladies’ man, and possessor of the greatest mane in Hollywood. Despite a fantastic career and the pick of any silver screen beauty, Lazlo’s life isn’t all nectar and roses: Someone is picking off studio personnel in a violent fashion, and the evidence starts to point in his direction. Of course, the bevy of angry former paramours doesn’t help, and on top of all that, Lazlo has a dreadful secret that he’s trying to keep. Lasiuta has a good eye for period detail, evoking the bustle and whirl of 1930s Hollywood so strongly that the words might as well be appearing in sepia, and efficiently keeps all the plot plates spinning right up to the last paragraph. And then…the whole damn thing crashes and burns at the end with a limp joke that doubles as the song title Lasiuta’s otherwise clever story was inspired by, although fans of metafiction may argue that Lasiuta was just keeping in line with Hollywood storytelling practices.

It’s back to the future with “A Prayer for ‘0443’” from David Niall Wilson, which shares a certain je ne sais quoi with Kurt Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron,” but goes in a more lyrical direction. In a world governed by the Fairness Act, which prevents people from forming attachments, competing in any way, or developing individual idiosyncrasies, a man named Boz works on a forbidden device. The device was once a phone, but through careful repurpose and dedicated engineering, Boz has a different purpose in mind. Although art and music are not forbidden, they only exist for a year, never to be repeated again, a state of existence that Boz can no longer tolerate, and decides to fight in the only way he can. While the setting of the story is neither unique nor particularly compelling, Wilson’s lyrical writing is both, and Wilson uses that skill to craft a story that works narratively in addition to providing a cogent rumination on the value of art. With a light touch, he guides the story to a conclusion that, while more hopeful than triumphant, provides a gentle satisfaction.

Another example of a story inspiring a Rush song is provided by “Gonna Roll the Bones,” the Hugo and Nebula-winning story by SFWA Grand Master Fritz Leiber. Dense with colorful, elliptical language, this tale of lowly miner Joe Slattermill and his amazing facility with dice playing against the sepulchral Mr. Bones has aged poorly in some respects. Its portrayal of the unnamed female characters is not particularly enlightened, for example, and there’s an ugly racial slur or two, but overall it remains a shadowy, seductive romp, with Leiber’s flair for oblique symbolism and sharp prose, not to mention a deceptively simple and beautiful final line.

Brad R. Torgersen lays his cards on the table with “Spirits with Visions,” a tale that paraphrases a line from the song that inspired it, and follows its emotional arc closely. Alberto, a young man from a poor but aspiring family, wins a VIP pass to the Kennedy Space Center to see a space launch, but the memory that Alberto registers most strongly is the sight of a former astronaut, now a paraplegic due to an accident, left behind as her colleagues head for another world. As the years pass, that memory drives Alberto on, as it does for Shar, the crippled astronaut left to pilot a desk for NASA. Both driven to do their best, both dreaming, their lives intersect in a way neither of them could predict. Subtle it’s not, but Torgersen’s tale is told with a sure grasp of technical detail and a cheery, change-the-world sense of optimism that is endearing without being naïve. A straightforward joy to read.

“Into the Night” by Mercedes Lackey takes readers into the world of ECHO—Extrahuman Coalition for Humanitarian Operations, familiar to readers of the Secret World Chronicle series. Vickie Nagy, a magician with the unique ability to work with technology, is on the hunt with her parents and godfather to find a metahuman responsible for several disappearances in Chicago. Easier said than done, even for a family that includes a werewolf and several flavors of magician, but Vickie brings more than just tech magic to the table. Readers familiar with Lackey’s series will undoubtedly get more out of the story than neophytes, but the characters and their relationships are laid out swiftly and clearly, and Vickie’s voice is engaging and self-aware. However, possibly because it takes part in an existing universe, the tale doesn’t precisely fit with the overall mood of the anthology. Also, fans of urban fantasy—particularly readers of Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files series, also set in Chicago—may simply find these streets too familiar.

Like a few of the stories that precede it, “Day to Day” by Dayton Ward suffers somewhat by taking its inspiration too literally. Captured by an alien race called the Pugs, Gabriel Ryder has been reduced to simple survival mode, eking out an existence in a concentration camp with his mother, haunted by the memory of seeing his father and brother killed. Isolated by overwhelming force and brutal efficiency, Gabriel isn’t even sure if other humans exist, but he’s not too despondent to take advantage of an opportunity when it arises. Rush told this story more effectively when it was “Red Sector A,” and though Ward’s writing shows considerable conviction and professional skill, the story brings nothing new to the table.

Part legal thriller, part meditation on grief, David Mack’s “Our Possible Pasts” relates the story of how an assistant U.S. attorney wins a high-profile case, while losing his professional detachment…but possibly gaining the world. Juan Robles is a respected attorney who gets tapped as a substitute prosecutor for a high-profile case, in which a senior citizen is accused of nearly 40 counts of murder. The defense? She told them that she could transfer their minds to a younger version of themselves, a feat which leaves their bodies behind, but gives them the chance to live again. On the surface, the case is unlosable, but as the weight of his partner’s recent death slowly strangles Juan’s heart, he begins to wonder if he’s on the wrong side of justice this time. Mack manages to commingle legal proceedings, quantum physics, and the psychological machinery of loss into an elegant narrative of hope and the human condition. One of the most keenly felt, and outright beautiful, stories of this collection.

The world post-apocalypse is almost as popular as dystopias in modern fiction, and Steven Savile brings hope and a respect of radio to the world of “Last Light.” Humanity has been brought low by the Lights, moving luminescences that burn and kill on contact, and the survivors are hanging on to what’s left by hanging all their hope on the Source, a mysterious radio broadcast that plays in the mornings, exhorting whoever is listening to keep fighting, keep trying. Pete, one of the last people in the area, and his cohorts abandon their refuge in an old shopping mall to find the Source. What they find isn’t what they expect, but it gives them something new, or rather, something they thought they’d lost. Despite the story’s length, the pacing picks up so much toward the end that the conclusion feels a little rushed, especially in Pete’s last monologue. However, despite that, Savile earns the transformation of Pete from lout to unsung hero with strong plotting and an unsparing self-aware honesty, and makes the hopeful bent of the tale believable.

The final tale of the anthology—“2113” by Kevin J. Anderson—is probably not the one they should have gone out on. Once again following the general arc of the original Rush song a little too closely, this tale of how the Elder Race (read: artists, engineers, makers and shapers) returns to Earth to unleash the forces of creativity and free humanity from the Temples of Syrinx (read: orthodoxy, bureaucracy) is, simply put, dull. For a story that repeatedly argues for the value of imagination, this interpretation shows little, a surprise from the normally reliable Anderson. As with nearly all the other stories, the writing itself is of clearly professional caliber, but in this case, it’s insufficient to muster interest. The editors might have been better off to swap the order of the last two stories for a more resonant cumulative impact.