“Fire Creek” by John M. Whalen

“Professor Malakoff’s Amazing Ethereal Telegraph” by Lou Antonelli

“Bad Justice at Yellowstone” by Norman Riger

“The Great Genome Robbery” by Trent Roman

“Message in the Dust” by S.A. Bolich

“Plague 8 From Inner Space” by Sam Kepfield

“A Fistful of Bad Guys and an Ugly” by David M. Fitzpatrick

Reviewed by Aaron Bradford Starr

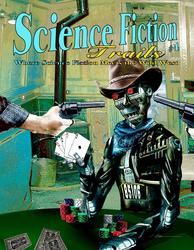

Though there is some dispute, the genre of science fiction is generally agreed to be anchored in some time from the present forward, from the standpoint of the writer. Written work ages, of course, and most of the speculation never comes to pass, or, even more disconcertingly, arrives sooner than expected, and far more advanced and powerful than imagined. So used are we to the idea of science fiction as being predictive in viewpoint, and of a forward-looking orientation, that a collection such as Science Fiction Trails can be perplexing. While the occasional historic slant to a science fiction story has been seen before, a group of seven all under one cover is unusual, and to have them all rooted in a time and place as specific as the American west during the tumultuous years of unfettered expansion is a project of some ambition. The fact that this is a recurring effort, repeated annually, says something about the love that David Riley-–the publication’s editor and publisher–has for the concept.

It’s somewhat unfortunate, then, that the final presentation of Science Fiction Trails fails to do the stories themselves full justice. The stories are sprinkled with typographical and editing errors, which impacts the way in which the entire collection will be received. However these anomalies are introduced, they will hopefully be addressed in the next edition, as the contents are worthy of a reader’s attention, as they serve as minor but real distractions.

The collection begins with “Fire Creek,” by John M. Whalen, a tale of perpetual outsider Avery Cameron. The opening is especially strong, establishing Avery’s superior abilities and his parents’ wary notice of them within a few sentences. Avery is summarily removed from school by his protective parents, and this serves to deepen both his isolation and the mystery surrounding his inability to fit with his fellow citizens.

Avery’s strange otherness is never demonstrated directly save through the reactions of the townfolk, and these are, at times, baffling, making the townspeople far more alien than Avery. Where Avery is concerned, the people of Fire Creek have little patience and no sympathy whatsoever, and this makes them seem heartless and distant, far less real, as if they exist just slightly removed from Avery’s reality. This serves to turn the people of Fire Creek into an almost animal presence, reacting viscerally to the subtle negative stimulus Avery causes in them.

Still, the tale rolls forward well enough until it hits a massive shift in tone. After a personal revelation by his parents shakes the foundation of his identity, we are primed to learn the truth through Avery’s eyes, following his growing knowledge. But that isn’t what happens at all, and it is here that “Fire Creek” trips badly, abandoning the personal tone of the setup, and simply begins telling what happens for much of the climactic scene. The science fiction elements of the tale are related to the reader using modern terminology that would almost certainly not have occurred to Avery or any other witness to the events. This shift in voice is detrimental to say the least. “Fire Creek” is a promising story that falls victim to the very narrative speed it builds so carefully in the setup. Still, it marks author John Whalen as a voice to watch for an ambitious ability to blend very disparate elements into a single story.

Lou Antonelli’s story, “Professor Malakoff’s Amazing Ethereal Telegraph,” spends its opening building a single coherent setting, carefully working into the narrative both the political preoccupation of post-Civil War Reconstruction, and the growing public awareness of the advances of science. Mr. Antonelli is careful to explain scientific particulars to the reader only when his character, the rather dubiously-named Dr. Eustace K. Malakoff, can find a willing audience.

And the details of Dr. Malakoff’s “ethereal telegraph” are very interestingly presented, making the so-called Professor less than a complete charlatan, but just enough of a trickster to intrigue. His ability to pull telegraph messages “from the ether,” as he claims, using just the power of his mind, is debunked for the reader before we ever see his show, and yet the potential for plot twists makes the story rumble forward unstoppably. Lou Antonelli has crafted a first-rate piece of historical science-fiction here, where the historical elements and scientific detail dovetail to make a strong, believable whole.

The tone of “Bad Justice at Yellowstone,” by Norman Riger, on the other hand, is the polar opposite, overwhelming the senses with all manner of strangeness from the beginning. The time is indeed the 1800’s somewhere, but the Triangle Empire is an inhuman bureaucracy that apparently needs cheap convention space to host galactic-scale get-togethers, and Earth fits the “backwater” part of the preferred locales.

The structure of a western is hidden under piles of xenobiology and strange dealings. The protagonists, rancher Ted White and his lizard-like sidekick Thepo, serve as maximum lawmen in this lawless place, racking up only complaints for their troubles. This short tale is more about enjoying the ride than going anywhere in particular, though, and all too soon it’s over, leaving a collection of strange impressions, more bemusing than beguiling.

“The Great Genome Robbery,” by Trent Roman, threads a different needle, predicated on the existence of a secret society of Pythagoreans surviving till modern times. Their final dip into the genepool of the larger society is the subject of this story, but it is in the deft handling of the protagonist, Winston, that Trent Roman’s writing shines. Whether dealing with supposed cattle thieves, or facing super-technological weaponry, Winston’s viewpoint never wavers, relating what he is seeing to the context of late-nineteenth century technology.

The climactic scene is well imagined and written, and the resolution is neat, allowing Mr. Roman’s prose to deliver readers safely to the other side of the story without seeing any of the potential cracks in the smooth veneer. A fine and high-minded story, giving a speculative glimpse into a deep well of stories, should Mr. Trent care to go there again.

Striking a similar pace and tone, S.A. Bolich’s “Message in the Dust” introduces us to knowledge-seekers Henry Carver, an Oxford-educated Englishman, and Sage, a Cheyenne Indian. The alien artifact they’ve stumbled upon in the wilderness is a source of psychic turmoil to all who touch it, drawn, no matter how unready for the experience, to a longing for the stars, and visions of a mysterious route through the local cosmos.

Like Roman, Bolich conveys complex, thoroughly modern imagery in terms any Oxford-educated man of the time might reasonably be expected to use, and Carver’s scientific detachment, which allows him to experience the alien message unscathed, is both a useful plot device and an excellent contrast to the temporary madness that overtakes his friend Sage at the story’s opening, after the Cheyenne touches the artifact.

The resolution of the tale is particularly interesting, marking Carver and Sage as wise enough to know their limits. The choice of two lifelong delvers into the unknown to forego knowledge they are unready for comes across as difficult, but they have been humbled by their experience, a surprising amount of character development and growth for such a short story, and one Bolich pulls off with skill and empathy.

A similar skill is displayed by Sam Kepfield in his story “Plague 8 from Inner Space.” Though the title would have readers perhaps primed for a spoofish parody of science fiction, the story is a plausible bit of historical speculation involving a rampaging swarm of mutant locusts. While S.A. Bolich’s tale relies upon the inner landscape of the protagonists, Sam Kepfield rests his events on a solid foundation of historical detail, but the story reads with all the speed of a pulp monster movie.

The characters relate to each other mostly as one professional to another, bound together by a shared experience in the recently-ended Civil War, and the pace of the story allows nothing more. But Kepfield’s characters still feel multi-dimensional, their sketched-in history giving a very strong sense of people set in their appropriate time. When the speculative elements of the story take over, and the locusts are confronted with technological weaponry and military tactics, the reader is willing to accept the rapid change of fortunes for humanity, which spent the opening of the story getting eaten non-stop.

The issue closes with “A Fistful of Bad Guys and an Ugly,” by David M. Fitzpatrick. This story opens well, with an enterprising young piano player striking out for adventure in the newly opened west. Casting the protagonist as the ever-present saloon piano player is clever, and the financial straits which force him into employment in Elmsworth City rather than continuing west are amusing.

But Elmsworth soon proves to be a tough frontier town, plagued by a man called Blackheart John. This particular man and his evil gang are the linchpin around which the story begins to suffer from serious cracks. Almost as soon as the man is mentioned, even before his actual arrival, the logic of the townsfolk –especially the never-seen sheriff—is revealed to be suspect, more acting out assigned roles than acting in their own self-interest. It just seems doubtful that a menace like Blackheart wouldn’t be hunted down by the local lawmen, deputizing people left and right, and calling on other towns as well. But it’s just the new sheriff and a couple of deputies, who do nothing of the sort for weeks after Blackheart shoots dead the former piano player in cold blood (after dispatching the previous sheriff likewise).

The character’s descent to cardboard continues with Blackheart’s attempted rape of the saloon-owner’s daughter, who is the love-interest of the protagonist. But the violent and disturbing incident is forgotten as soon as it is interrupted by the arrival of an alien being who, for reasons unknown, is visiting the town and wants to play gunslinger. The girl, Merry, simply pulls up her clothes, as it were, and begins rooting for the alien to shoot Blackheart down. This is in such contrast to the emotional reality of imminent rape that it shatters the plausibility far more than the alien does. There may or may not be aliens, but rape does exist, and it doesn’t look like this.

Fitzpatrick is clearly skilled at crafting varied and likeable characters. But “A Fistful of Bad Guys and an Ugly” tries to get in too much, and the believability suffers for it. The much-needed scoundrel is too over-drawn, and the shootout too much of a cliché. This image, of the hard-core bad man facing off against the alien in a classic high-noon style confrontation, is clearly the central motif, but the gymnastics required to achieve it make the rest of the story suffer. In the end, the story’s greatest failing is from too light a tone, making the real evil being detailed seem trivial.

Science Fiction Trails, Where Science Fiction Meets the Wild West, #4 ($7.50)

Published annually by David B. Riley

P. O. Box 8191

Avon, CO 81620