“Shadow of the Valley” by Fred Chappell

“The Texas Bake Sale” by Charles Coleman Finlay

“Winding Broomcorn” by Mario Milosevic

“Catalog” by Eugene Mirabelli

Reviewed by Mark Rigney

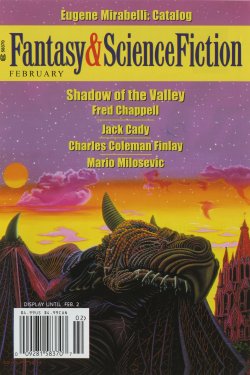

This issue begins with Fred Chappell‘s “Shadow of the Valley,” hiking up its linguistic skirts to a more rarified plane than 2009’s day-to-day grunts of “yeah” and “hey” and “wassup.” Our hero and first-person guide is Falco, a mercenary and herbalist’s apprentice, and in his hands, the speech patterns of past centuries are revived and recalled, but never more faithfully than is required for an enjoyable reading experience. (If one really did write characters who speak like the creations of H. Rider Haggard, how far would most present day readers get––and who would blame them for quitting?) In this sense, the story is a formal experiment, a trick of the verbal light: Just how antiquated can modern English become before it becomes dusty, a distraction instead of spice and flavor? It’s a Tolkienesque balancing act, one that many fantasists have attempted with varying success, but here Chappell never veers so far from the story at hand that the language itself becomes the story.

That said, this humble reader did find himself scurrying for the dictionary, the better to comprehend Chappell’s offered broadside of “conturbeth,” a word which my fifty-pound Webster’s stubbornly refused to yield. A Google search came up…blank. Now how often does that happen? I was reminded of two things, the first being my four-year-old’s happy tendency to make up random non-words using refrigerator magnets, and also my occasional foray into the use of made-up words for purposes of my own stories. Conturbeth, however, turns out to have a precedent after all, as revealed by perhaps the only remaining lexicon that can topple Google in a single bound, The Oxford English Dictionary. The OED reveals “conturb,” with a first usage dating to 1393, and meaning “to disturb greatly, perturb.” To Chappell’s credit, the context of his use of “conturbeth” was always clear to a fault, and frankly, seeing Google hit a brick wall was worth the price of admission in and of itself. Besides, thanks to Falco and company, my vocabulary groweth apace.

Falco’s job––his quest––is to bring back to his master, Astolfo, a wide selection of shadow-plants, flora that grow only in a particular shaded vale in distant mountains. Chappell wisely hands Falco more than just a difficult prize, he also gives him a deadline: Falco is in a race to obtain these specimens with his master’s other apprentice, a wonderful creation indeed, a man cursed with a cat’s voice, Mutano. Falco knows he needs help, so he allows himself to be captured by a banished lordling and his brigand band specifically that he may recruit them to his cause. This he does, displaying both wit and courage, and so this little troop of six begins the long journey to the Shadow Valley.

As with heist movies and Tom Clancy thrillers, “Shadow of the Valley” thrives on the appeal of the expert, in this case Falco. He’s a man’s man, the icon of so many Westerns, the sort who can accurately predict the motives and movements of others, then exploit them to a tee. He has no emotional connections of any kind (indeed, women and children are notably absent from the story), and would likely deny needing any such thing. For experts, need is weakness. Think of Moorcock’s Von Bek, Fleming’s 007. We love these all-knowing cynics at least in part because they are so patently broken. Like them, Falco is the sort of tough-guy who fantasy readers cotton to easily; his smarts and his world-weariness are butter for the bread of our reading experience. And so the story’s success stands or falls on Falco’s confident, wary shoulders; we follow the turns of this short story-cum-novelette to the degree that we bet for or against Falco’s success. Will he and his outlaw band reach the prized plants before Mutano, and will he get them back to semi-safe civilization before misfortune overtakes him? The pages turn readily in search of the answers.

Chappell does not coast on Falco alone. He conjures a supporting cast, some human, some not, and the latter in particular charm the story into a broader, deeper life. This secondary cast is made up of shadows––literally––including Falco’s own, for in Falco’s world, shadows are not insensate tricks of the light. If not precisely ambulatory, they do exist somehow separately from those creatures and objects that cast them. It’s a wonderful conceit, eerie and atmospheric, and provides a ready counterpoint to Falco’s resonant and fault-filled humanity.

The story ends quietly, a surprising discovery given the looming violence implied by the set-up; one reads through Falco’s many narrow escapes with the rising and justifiable expectation of something more dreadful to come. That said, the story’s close is by no means a disappointment. The journey is complete, the arc of the the tale sewn neatly shut. Astolfo will no doubt send Falco on another errand soon enough.

Charles Coleman Finlay’s “The Texas Bake Sale” plants its flag firmly in the post-apocalyptic sands of dust-dry Texas, and asks us to consider the somewhat absurdist idea of rogue military units subsisting on the bake sale proceeds of middling cookies and over-baked zucchini bread. You’ll refuse to buy, of course, but once the mercenaries in charge waylay your vehicle and aim a few rifles at your head, perhaps a brownie might sound good. The price? A tank of fuel and as much money as you’ve got on you.

“Marine” Captain Mungus, the elected leader of this particular band, has a truly lousy day during the course of Finlay’s narrative, a day dominated by a backfired attempt at extortion that costs a fair number of his unit their lives, but ends on a satisfactory note (for Mungus) in that he and his troops defuse a trap meant to kill them and wind up with enough ammunition to soldier on for the rest of their tawdry lives. Pointlessly, to be sure––but so it goes in a world where government is gone and all it takes to grab a little power is backup, guns, and a long-abandoned interstate road-side rest area to commandeer as a base.

“The Texas Bake Sale” hooks strongly into the topical zeitgeist of the moment, as Mungus bristles at the accusation that he and his semi-merry band are “nothing but pirates.” They are, of course, but with Mungus ensconced as hero, it’s easier to forgive him his sins than it is to accord distant Somalis on the Gulf of Aden the same. Pirates are as pirates do––unless, like Mungus’ trusted lieutenant, they still wear the badge of the 1st Reconnaissance Marine Battalion.

Once again, two stories in, and there’s not a single female character to be found. This changes immediately in Mario Milosevic’s “Winding Broomcorn,” in which a widower continues his family tradition of making brooms the old fashioned way, and in so doing learns a key fact about his wife, a blazingly important point that he had somehow, during their long marriage, altogether failed to appreciate. Despite the fact that the story treads rather heavily on certain fantasy tropes such as “and when I awoke the next morning, it was as if the (fill in the blank here) had never been” and “I am a pastor who has now renounced God because God is so annoyingly unjust,” the narrative gets its bearings in the lucid, compelling specificity of the broom-making itself. Milosevic clearly knows his stuff––or is a dangerously accomplished liar––and in its way the story works best as an elegy to a dying folk-art. Were I to meet Dwayne, our narrator, by some fictional fluke of a worm-hole tomorrow, I would humbly and immediately ask him to make me a broom.

Linguistically, this is simple stuff, a story swept clean of clutter and long sentences. No fourteenth century terms litter this landscape. Conversations proceed with brevity and economy, as in:

“Harold was right next to me. ‘That what you were looking for?’ he said. ‘This broom?’

“‘Yeah,’ I said.

“‘Not one of your better ones,’ said Harold.”

Efficiency, then. Form follows function. In a story about brooms and letting go of loved ones, Milosevic sees no reason to gum up the works with verbosity, but in a (real) world packed with work like The Year of Magical Thinking or even Tuesdays With Morrie, the heartstrings resist being tugged too quickly, and the short story form is rarely a cathartic experience. So, too, here. Dwayne ends in a new place, ready to move forward from two years of slow, broom-centered mourning, but it is too much to expect that most readers will feel an equal emotional punch. If one were to gather two buckets and fill the first with all the tears shed by short-story readers, and the second with the tears teased out by novels, can there be any doubt as to which would fill the faster?

The final original offering in this issue of F&SF comes from Eugene Mirabelli, with “Catalog,” in which a somewhat dazed semi-hero named John stumbles into an alternate universe that turns out to be––but perhaps isn’t––the world of the glossies for which he works as a graphic artist. He arrives in an auto dealership, of course, then has the “pleasure” of sleeping with the almost literally two-dimensional model who’d shown off the cars. The world is not entirely predictable, however, and after a brush with some Dick and Jane-style characters chasing Spot in a park, John bumps into a bevy of slackers pulled from the backlist of Edgar Allen Poe, including the House of Usher (yes, the house itself) and Annabel Lee from the eponymous poem. What do Poe characters do in a magazine-dominated universe? They form a Bohemian enclave and jump-start an indie rock band. Isn’t that what you’d do, in the face of your tell-tale heart?

John perseveres, and the story moves from the suddenness of punk fictions to a languid, romantic pitch that finds John tracking down his newly confessed true love, an upper-class beauty-with-brains who models sweaters for L.L. Bean. And why not? Prince Charming always was a trifle two-dimensional. Why should the same not hold true for Princess Charmette?

From the moment I opened this issue and caught the title “Shadow of the Valley,” I was powerfully reminded of my all-time favorite fever-dream story, a piece that appeared in Esquire back in August of 1945––in the days when fiction in Esquire still mattered. Penned by T.K. Brown III, the story in question is “The Valley of the Shadow,” and it has long since fallen into undeserved obscurity. (It did manage to get reprinted in Best American Short Stories 1946, but so far as I know, its life largely ended there.) Its plot is not germane to my point, but its position in history is. Look at some of Esquire’s other great offerings of the period: Pietro di Donato’s “Christ in Concrete,” Langston Hughes’ “A Good Job Gone,” and Ray Bradbury’s “The Illustrated Man.” These three have survived. Most have not.

Will the four originals debuting at the ballyhoo ball known as the February 2009 F&SF still be read in eighty or a hundred years? Or will fatigue, and an infinite number of new offerings eclipse their standing, their obvious fantastical pleasures? Only time will tell, and shadows await in the corners, even in the best lit libraries, seeking the merest opportunity to swallow even our finest fictions. But there is hope yet, springing eternal like next winter’s L.L. Bean catalog (glossy!), for even as magazines come and go and stories fade from memory, “conturbeth” lives on. Thank you, Mr. Chappell, for proving once again that fiction, and perhaps especially genre fiction, has within it the mighty power of resurrection.

Mark Rigney is the author of the play Acts of God (Playscripts, Inc., 2008) and the non-fiction book Deaf Side Story: Deaf Sharks, Hearing Jets and a Classic American Musical (Gallaudet University Press, 2003). His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and appears in The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, All Hallows, Talebones, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine, Traps, Shelter of Daylight, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. For recent fiction and a massively long interview, check here. His website, with links to many of his original stories, is www.markrigney.net.