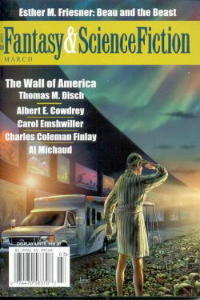

Novelettes

"The Amulet" by Albert E. Cowdrey

"Ayuh, Clawdius" by Al Michaud

"Love and the Wayward Troll" by Charles Coleman Finlay

Short Stories

"The Wall of America" by Thomas M. Disch

"I Live With You" by Carol Emshwiller

"Late Show" by Gary W. Shockley

"The Beau and the Beast" by Esther Friesner

"The Wall of America" by Thomas M. Disch

"I Live With You" by Carol Emshwiller

"Late Show" by Gary W. Shockley

"The Beau and the Beast" by Esther Friesner

This issue features a nifty variety of stories, well-suited to the season: dark, cold days interspersed with delightful glimpses of spring. Humor, adventure, a dash of horror.

This issue features a nifty variety of stories, well-suited to the season: dark, cold days interspersed with delightful glimpses of spring. Humor, adventure, a dash of horror.Thomas M. Disch‘s "The Wall of America" is short, cleanly written—and agreeably puzzling, at least for this Bear of Little Brain. As soon as I finished (it’s quite short) I went right back reading more slowly for clues. This time I noticed just how effortless Disch’s prose is, vivid, smooth, with a distinctive voice, and I got a glimpse of the flames’ reflection on the cave wall.

The setup is simple: this is the near future, and a wall bisects the USA from Canada, along which artists are permitted to hang their paintings, large and small. Lester was not even a painter until an accident put him in therapy, during which he discovered he liked to paint. Now, two months out of each year, he leaves his wife behind and lives in his Winnebago at the north end of North Dakota, while he works on his paintings. His rewards are the spectacular sunsets, whose colors he tries to match, and the nightly light show of the Aurora Borealis, whose beauty seems to partake of the infinite.

One night a pair of headlights comes cruising along slowly, and it turns out there’s a young man who wanted to see the paintings along the wall. He wished to see Lester’s by night. He stops, they crack open some beers and start to talk . . .

The setting of "Ayuh Clawdius" by Al Michaud appeared once before, in July 2003. The story concerns the inhabitants of Clapboard Island, Maine, focusing on one Clem Crowder and his sidekick, Dunky Drinkwater. Clem, who is a few fries short of a Happy Meal, had to sell his fishing boat after he managed to give food poisoning to the entire town at the clambake. He’s not quite making a living now at carving scrimshaw, when he finds himself visited by a booming rich Texan named, well, Tex. It turns out Tex is going to set up a fancy resort on the island, and is throwing money around in typical Texan style; he also has to have the biggest and best of everything, which includes Clem’s ancient blue lobster, Clawdius.

Clawdius is by way of being a family pet. Not a fond one, but, Clem realizes only after he sells Clawdius to Tex, an important one: a vision of his browbeating wife (blessedly away on a two year cruise) and his even more browbeating father and grandfather convince him of his error. So he needs to get Clawdius back, but Tex refuses to take back his money. Clem forms a plan, which involves retrieving his boat, and dealing with some extremely odd characters—not excluding the ancient Sea Crone . . .a delightful tale, with an unexpected, ah, snap at the end.

And for one of those radical sea-changes, Carol Emshwiller follows next with "I Live With You." Emshwiller is one of those writers who can bring off a story told in second person present tense. It opens: "I live in your house and you don’t know it." Immediately I heard a whispered echo of Emily Dickinson’s poem: "I live with him, I see his face; I go no more away/ For visitor, or sundown, Death’s single privacy…"

Though the narrator proceeds to tell us the intimate details of the life of the story’s ‘you’ this is not about stalkers, any more than the Dickinson poem is about stalkers. It’s about the boundaries of identity, the invisible walls between human beings, those we create and those we seem to find imposed. Crucial lines in a Carol Emshwiller piece will differ for different readers, depending on what experience we bring to the story. For me, the crucial line is ""But I don’t suppose that lock will hold against two people who really want to get out." Read it, see what you think.

Gary W. Shockley‘s "Late Show" is light-hearted in tone: its form is a transcript of a TV show being taped at the Ed Sullivan Threater in New York City—in which the guest is an alien. Though there are plenty of laughs, you get the feeling that a size triple Z double-wide shoe is going to drop—and yeah. A nifty story with a zippy ending, just the right length.

Charles Coleman Finlay follows with a long novelette called "Love and the Wayward Troll," which the introduction says is a portion of a forthcoming novel. The setup—a human young man named Maggot, raised by trolls, goes out to seek a mate—promises slapstick humor, but that’s not quite what we get. Not that Finlay disappoints one’s expectations of the comedic side of this situation. There are some genuinely funny moments—Maggot’s pickup line is spectacularly hilarious—but he manages to make a good story out of Maggot’s attempts to parse the mysteries of human culture (not to mention the mysteries of mating) while also learning to survive. A good story, well written—I look forward to the novel.

And wrapping up the issue is Esther Friesner‘s "The Beau and the Beast." This story is presented in epistolary form, which is appropriate to the turn of the nineteenth century; the tone is a kind of manic Georgette Heyer as a hapless maiden is sent to her crazy aunt at Brighton in order to find a wealthy husband. When our heroine discovers her aunt is a member of a secret religion as well as the more conventional C. of E., she loyally attempts to join . . .nope, no more clues. Look back at the title, and be prepared to laugh out loud.