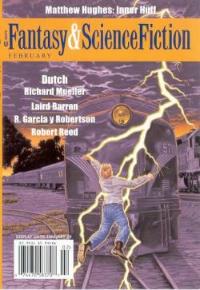

Novelettes:

"Inner Huff" by Matthew Hughes

"Queen of the Balts" by R. Garcia E. Robinson

"Proboscis" by Laird Barron

Short Stories:

"From Above" by Robert Reed

"Dutch" by Richard Mueller

This issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction features three novelettes and two short piecessustained reading for these long winter nights. The mood and mode vary across the spectrum from humor to horror, which, adding in interesting reviews of current books and films, makes a satisfying issue.

This issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction features three novelettes and two short piecessustained reading for these long winter nights. The mood and mode vary across the spectrum from humor to horror, which, adding in interesting reviews of current books and films, makes a satisfying issue.

Readers who enjoyed Matthew Hughes' "A Little Learning" last year will be glad to see another story set in the far future Archonate, "Inner Huff," wherein everyday life for the Fellows of the Institute for Historical Inquiry intersects with the mysterious noösphere. Familiarity with Jung, Chardin, and especially Jack Vance give Hughes' stories an extra layer or two of resonance, but I don't think readers have to be familiar with any of them to find entertainment in Hughes' smooth, humorous style, his eye for ironic or just plain weird detail, and above all the names. Who could really trust a fellow scholar rejoicing in the nom de robe Didrick Gabbris?

Guth Bandar is mind-traveling in the noösphere, collecting examples of siren songs, which he believes will support his thesis that not all archetypes have been long ago recognized and categorized. These journeys are not without risk, but Bandar is well-trained, knows the rules and how to find his way between Locations where the archetypes perform endless reenactments of their myths. Only dirty work is a-wing in the noösphere, and Bandar finds his solutions landing him in steadily worsening archetypal situations until his life is threatened by a cataclysmic nightmare.

Robert Reed's work appears frequently in this magazine; he is a prolific and skillful short fiction writer. "From Above," like most of his stories, is not connected to any of his other work, but exists on its own.

Nine-year-old Manny is with his Cub Scout troop practicing survival skills in the woods, when the older boys decide to chop down a tree just to see if they can do it. Only Manny recognizes the species, and only Manny realizes when their inexpert axe-wielding has succeeded in killing the tree. He hates the ignorant, careless cruelty, but is powerless to stop it, when a voice speaks nearby, insulting them all.

The boys discover hovering in the air a round thing like a balloon, from which the voice emanates, telling them their secrets, and insulting them. One boy tries to smash it, with disastrous results, and all the boys run. Soon the authorities stream back to investigate what the boys reported, and the neighbors living on the periphery of the wood emerge, one of them being the brilliant Jonah Klast, raised by a possessive mother to achieve the top prizes the world has to offer. It's only he who can address this abusive being, who seems to know the past and future of everyone, and scorns them all for their helpless limitations.

I read fast, mesmerized; for me, the story progressed in exponentially greater shifts to dream logic rather than real. We never see the conversation between Jonah and the entity, only the results, which begin on a grim note and rapidly get stranger. One for the category of Seriously Weird.

R. Garcia Y Robertson, like Matthew Hughes, has published a series of stories about the fantasy world Markovy, but like Hughes' story, "Queen of the Balts" stands on its own. Markovy reminds me of Grimmelshausen, a grim, grotty period in which the ugly realism of constant warfare exists side by side with magical possibility.

Princess Annya of Zilvinas finds her land about to be invaded by not one, but two armies. There is no way to stop the invasionher force is too smallbut she is determined to save her people. She rides out alone, encounters Prince Nikolas of Pzkov as well as the Teutonic Knights of the Sword, in their unholy quest to supposedly conquer the Balts for Catholocism, but along the way there seems to be lots of looting, burning, rapine and slave-taking to be accomplished first. All of these Markovite stories move at a headlong pace, and are impossible to predict: Robertson's adventure tales skillfully veer between dark fantasy and light, keeping the reader riveted until the last line.

Laird Barron's "Proboscis" is, as the title might suggest to others who, like me, find insect biology interesting but ultimately kind of creepy, a nifty horror tale. Our first person narrator is part of a team who travels around videotaping crime scenes; sometimes the perpetrators get caught, as happens early on: the target is s a serial killer, accompanied by a young girl, who delights in teenage female victims. The guys are there to see him get nailed, though it isn't easy; meanwhile the narrator is regretting his lack of skills as husband, and especially as parent of a daughter. He calls home from time to time, and you think you know where the story is going, but it takes a serious sidestep when he figures out there's something bizarre about these murdersand the murderers. Join him on an extremely wild ride, right to the very last line.

The last story is Robert Mueller's "Dutch." This story reminds me of some of Theodore Sturgeon's tales, featuring strong characterization set against a convincing backgroundin this case the trains crisscrossing the United States over a couple of decadesadding in just a touch of strange. It's a simple tale, a satisfying tale for those who like a little justice in fiction, even if we can't always get it in life, and thus an excellent close to an issue well worth keeping on the shelf and revisiting from time to time.