Note: This post was imported from an old content-management system, so please excuse any inconsistencies in formatting.

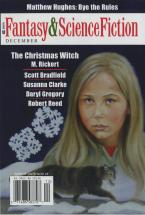

“The Christmas Witch” by M. Rickert

“Damascus” by Daryl Gregory

“Dazzle the Pundit” by Scott Bradfield

“Pills Forever” by Robert Reed

“John Uskglass and the Cumbrian Charcoal Burner” by Susanna Clarke

“Bye the Rules” by Matthew Hughes takes us on yet another thrilling adventure in the noösphere, the collective unconscious wherein all the mythical stories of humanity are endlessly repeated. Although this is a continuing story, you don’t have to be familiar with what happened before to enjoy the adventure on its own.

In the penultimate days of Old Earth, our hero Guth Bandar has been ousted from his post as an adjunct scholar at the Institute for Historical Inquiry, largely due to the influence of his academic rival, Didrick Gabbris. Both Guth and Didrick are skilled in what might be considered controlled dreaming, traveling about the collective world of dreams, researching man’s accumulated psychological history. In his previous adventures, Guth became convinced that the collective unconscious had, itself, become self-aware and was actually directing some of the actions taking place in the dream world, rather than mindlessly repeating long-established situations and events. Perhaps he should have kept his opinions to himself. To his colleagues, change is anathema, and new ideas are to be actively discouraged. This world of Old Earth is essentially stuck in a rut and likes it that way.

Now Guth works in his Uncle Fley’s housewares vendory, selling such staples as insipitators, devices designed to remove all the flavor from food, in accordance with the local citizens’ practice of leading a miserable, or at least bland, existence. Although he misses the academic life, Guth is grateful to have a home and job, and is fond of his uncle. Things could be worse. And soon will be.

Not content with having destroyed Guth’s academic career, Didrick has found a new way to torment him. Their confrontation within the dream world is a wild journey from one archetypical situation to another, and neither is playing by the rules.

“The Christmas Witch” by M. Rickert takes us from Halloween to Christmas in the little town of Stone, where the children all collect bones, “following cats through twisted narrow streets, chasing them away from tiny birds, dead gray mice (with sweet round ears, pink inside like seashells), and fish washed on rocky shore.” Their parents, who probably were bone collectors in their childhood as well, seem to have forgotten the reason for this, seeing it as one of those childhood phases that surfaces for a time, then disappears. Perhaps you have to be young enough, or desperate enough, for the witch—if that’s who it is—to communicate with you.

If you’re one of those adults who think childhood is a time of sweet innocence, then either you had an atypical childhood, or, like the parents of Stone, you’ve forgotten a lot. Rickert takes us below the sunny surface of childhood to where all the fears and secrets, confusion and misunderstandings lie. Young Rachel, bereft of her mother and virtually friendless in a strange place, does her best to navigate through the baffling world of adults, who in their arrogance—or possibly willful stupidity—can’t hear or understand what a child tells them because they’re convinced they already know the answers. And of course, they never explain anything, assuming a child understands their hints and euphemisms, and apparent misbehavior is always intentional. Sound familiar?

Through Rachel’s sometimes sad, sometimes funny tale is woven a wisp, a ghost as it were, of another story, that of Wilmot Redd, who long ago was hung for witchcraft. Is it Wilmot’s ghost or something else that demands that the children collect bones? Who or what leads Rachel to assemble her collected bones into the shape of a “funny little creature” who dances for her? Was it witchcraft that killed Melinda, the babysitter? Is it Wilmot who calls Rachel to the Old Burial Hill just before Christmas? And was that really a mouse in the closet? I don’t think so. A delightfully eerie story.

“Damascus” by Daryl Gregory offers us religion in the guise of a disease, or vice versa. Chillingly realistic, it presents a glimpse of what could happen if even one ambitious, efficient medical professional were convinced that bio-terrorism was the road to salvation.

Paula has been sinking into alcoholism and depression since her divorce. Her neighbors, the women in the yellow house, decide to save her from her life of misery and despair. They befriend her and her daughter, offering food and friendship initially, patiently preparing her for conversion. In time, Paula “sees the light.”

The ladies have moved slowly in the past, selecting their future “missionaries” with care, one at a time. In a twisted parallel to the story of the apostle Paul, Paula becomes a zealot, determined to bring the joys of religious ecstasy to as many people has possible.

You may find parts of this story offensive or shocking, but you definitely won’t find it dull.

Enough of dreamscape battles, scary bones, and epidemics—take a moment to relax with a shaggy dog story. In “Dazzle the Pundit,” Scott Bradfield takes a lighthearted look at German philosophy, the nature of existence, and the possible psychotherapeutic benefits of American sitcoms.

Dazzle, the famous and highly self-educated dog, has been awarded a Seymour Fischer Guest Professorship from the Free University in Berlin as a guest lecturer in Post-Humanist Studies. No need to speak German, Dr. Krantzbaum assures him; the students are fluent in canine.

Despite Dazzle’s initial misgivings, his lectures are well-received. The students listen attentively to whatever random thoughts happen to come to him, and he is equally popular with his students outside the classroom. The only fly in the ointment is Heinrich, an overly-intellectual young man who wants to engage Dazzle in complex philosophical discussions. Although Heinrich focuses heavily on the misery and futility of existence, he doesn’t seem to be capable of examining his own unhappy life with a view to improving it. What’s a doggy professor to do? The answer may be unconventional, but it works.

“Pills Forever” by Robert Reed might be considered a reasonable extrapolation of our current quest for eternal youth. It also might make you think about whether it’s worth all the time, money, and effort to continually prolong a life whose only purpose appears to be continued existence. Not a simple question, really, and one we all may be faced with sooner or later as an aging population becomes increasingly susceptible to diseases of the nerves and mind.

The narrator avows that his main goal in life has always been to live as long as possible. He begins a fitness routine early on that gradually expands until it takes up as much time as a regular fulltime job. His income is primarily spent on maintaining his health—and that of his cat, who has outlived most of the people in his life. But cats, despite the best of care, age more rapidly than people. Eventually, our hero is faced with a decision. What would you do?

Last but certainly not least, we have “John Uskglass and the Cumbrian Charcoal Burner” by Susanna Clarke. In this folktale, we learn how a simple, uneducated peasant got the best of the powerful Raven King. The story could be taken as a cautionary tale, pointing out to the rich and powerful that the poor and weak have feelings too, and may not readily accept arrogance and abuse.

John Uskglass, the Raven King, and his hunting party trample through the clearing where the Charcoal Burner lives and work, destroying everything. To add insult to injury, the king, who is a powerful magician, turns the Charcoal Burner’s pet pig into a salmon. There’s no malice—it’s more on the level of swatting a fly and promptly forgetting about it. It never even occurs to the king and his companions that a peasant might take issue with having his home and livelihood destroyed—assuming they even noticed what they had done.

A properly indoctrinated peasant would probably have accepted the king’s right to do whatever he pleased, or at least been afraid to retaliate in any way. But this man doesn’t recognize the king, doesn’t think the matter through, and in his outrage storms off to enlist help from higher powers. The battle is on and continues to escalate until the king finally gets the point, or at least learns to avoid this particular peasant.