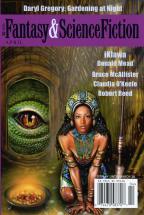

Cover art by Maurizio Manzieri

Novelets:

“Gardening at Night” by Daryl Gregory

“iKlawa” by Donald Mead

“The Moment of Joy Before” by Claudia O’Keefe

Short Stories:

“Starbuck” by Robert Reed

“Cold War” by Bruce McAllister

“Starbuck” by Robert Reed

“Cold War” by Bruce McAllister

April’s issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction offers a group of stories perfect for a send-off. In several tales, the characters grapple with death and new beginnings. Where do we go from here?

Daryl Gregory’s “Gardening at Night” sneaks up on you in the best of all possible ways. Set sometime in the present day, the story follows Reg, engineer of recombinant mine-detector machines (called “mytes”). As he tries to dictate the complex actions of the increasingly puzzling mytes, his own life becomes more chaotic. He, his wife and his son lurch awkwardly about as they negotiate the family’s separation. To top it off, Reg’s wise mentor, creator of the mytes, is dying of drug-resistant tuberculosis. What’s the point of it all?

Reg learns the answer in a place where he least expects it: his mentor’s mischievous programming of the mytes leads to…well, I won’t say, but it’s something unexpected and striking. Set up by Gregory’s methodical, understated craft, the climax brings the novelet’s elements together smoothly. The climactic, literalized metaphor (it involves superseding boundaries) gains its power because it rises without stylistic contortions from the down-to-earth, accessible prose. While the author’s clever allusions can border on self-congratulation, well-turned similes like the one in which Reg’s young son thinks, sitting “quietly as a Schrödinger cat,” make you think. Gregory’s prose gives a muted, interesting twist on the human search for meaning in life and death.

After “Gardening,” “iKlawa” by Donald Mead challenges you in a different way. Set in 1879, when the Zulus were chafing under British colonial rule, the story follows Zululand king Cetshwayo. He uses arms, strategy, and the help of his imperial ancestors, summoned by diviners, to ensure his culture’s survival. Meanwhile, the magicians at his aid fight their own battle for supremacy, and unexpected complications arise when the summoned supernaturals get out of control.

Mead immediately engages the reader with his vivid depiction of 19th century Zulu life. He weaves the details of the culture flawlessly in with fast-moving dialog that shows characters animated by the familiar lusts for fame, power, and sex. While I found the swarms of minor personages and their ranks confusing, I was carried along by Mead’s portrayal of the Zulu world. Though the story’s events shade into the fantastic, the story’s realistic, unsentimental presentation of history grounds it and draws you in.

Sadly, the fantastical aspects of “iKlawa” did not interest me as much as the historical. The illusions that characters cast on each other—to increase sexual appetite, to remain invisible—seem natural and appropriate, especially given the power struggles and deceit among the characters; however, the incarnation of ancestors and gods doesn’t work. Manifesting without much stylistic preparation, the warriors and lizard deities are faintly absurd. They lessen the human drama inherent in Mead’s finely wrought historical setting and feuding characters.

“Starbuck,” the next story in the magazine, takes us into an all-too-possible future, where nanotech, AI and new forms of doping complicate the issue of cheating in baseball. The titular pitcher in Robert Reed’s tale relies solely on brains and God-given skill; yet he still manages to beat his semi-mechanical opponents.

Reed’s gritty writing, combined with his convincingly logical extension of our current obsession with athletic performance, draws “Starbuck” out from genre sports fiction and into the broader realm of thought-provoking sf. In a game populated by modified and enhanced players, what does it mean to cheat or to follow the rules? What edge, if any, do “regular” humans have?

Given his detailed setting and the lovingly described physicality of all the players, Reed appears to be building up to an interrogation of the human condition. Therefore, the sudden joke’s-on-you brings the story to a thematically inconsistent close. I don’t expect transcendence from all my reading material, but I think that Reed could have pushed “Starbuck” to greater complexity and strength.

People again mull over the inexplicable and profound in Bruce McAllister’s short-short “Cold War.” In this vignette, set in the post-WWII era, a boy and his parents watch a Russian satellite, or possibly a UFO, sail overhead. The characters’ unresolved wonder and their straining toward enlightenment are evoked with the crystalline precision of a Ray Bradbury tale. At first, this story pissed me off because I couldn’t figure out exactly what the boy and his parents were looking at. Then I realized that was McAllister’s point. Sometimes transcendence appears, and you’re not exactly sure what to do.

“The Moment of Joy Before,” a novelet by Claudia O’Keefe, closes this issue. A new strain of an old disease appears in this story, as it does in Gregory’s “Gardening at Night,” but here it’s a mutant flu pandemic. Protagonist Felice tries to organize her life in the face of disaster. But her mother dies; then her daughter, her only remaining kin, falls sick; plus there’s this dangerous, but strangely gentle, man hanging around…

While similar in structure and themes to “Gardening at Night,” “Moment” packs a more visceral punch. Set mostly in a rural cabin among mountains of great beauty and loneliness, “Moment” follows the undulations of Felice’s perceptions as she confronts impending doom. The zeroed-in focus on Felice and the earthy, unforgettable prose—“Slanted, late daylight transmuted snowflakes from ice white to gold, sunlight given mass that soothed her fevered cheeks”—make “Moment” the most intimate of the stories in this issue.

While “Gardening at Night” charms your brain, prodding your analytical side and your intellect, “The Moment of Joy Before” grabs you by the heart. Immersing you in Felice’s life, O’Keefe carries you along with a style as light and swift, but as full of meaning, as a fairy tale. Supernatural powers hover on all sides of the protagonist until they finally break through, propelling the story from dystopian fantasy into magical realism. With an allegorical gesture reminiscent of the wise and melancholy Garcia Marquez, O’Keefe balances hope and sadness as, in the end, Felice finds transcendence in what she’s been trying to avoid: namely, death. I’ve spent my entire history distancing myself from characters’ travails, but “Moment” made me cry.