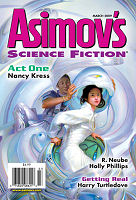

“Act One” by Nancy Kress

“Act One” by Nancy Kress

“Intelligence” by R. Neube

“The Long, Cold Goodbye” by Holly Phillips

“Slow Stampede” by Sara Genge

“Whatness” by Benjamin Crowell

“Getting Real” by Harry Turtledove

Reviewed by Robert E. Waters

“Act One” by Nancy Kress deals with the physical, psychological, and social repercussions of genetic engineering in children. In the near future, bio-terrorists have unleashed a “genemod” called Arlen’s Syndrome which is supposed to make children kinder, more empathetic. Not necessarily a bad thing, you might say, but when dealing with genetics, one can never know the side-effects. Genetic modification is the uncharted territory of our future, and Kress weaves a brilliant tale populated with many odd, yet very human, characters: Barry Tenler, a dwarf and celebrity manager; Jane Snow, an aging star who’s researching a part in a movie dealing with genetics; the Barrington twins Belinda and Bridget, who have been infected with the syndrome; Leila, Barry’s very angry ex-wife; and Ethan, Barry’s son who’s also been genetically altered with side-effects that make him prone to rage. What I liked the most about this story was its effortless manner in dealing with our obsession with celebrity, our wedge-issue politics, the media’s overly aggressive pursuit of “the scoop,” terrorism, and our fear of what’s different and unknown. What will be the final result of genetic engineering? The story suggests that it’s going to be a tangle, and that it will be difficult to determine which behaviors are caused by genetic tampering and which are simply caused by human nature. I’m certain Kress is right.

R. Neube is known for his little odd-ball tales, and “Intelligence” ranks with the best of them. Aaron works on an artificial intelligence project named ‘Bob’. This little AI is quite capable, but also consumed with conspiracy theories and get-rich-quick schemes that cause our protagonist no end of grief. And now Bob has a taste for freedom and connives with Aaron’s sociopathic girlfriend to bust out and prepare for the arrival of alien overlords. Wacky indeed, but quite enjoyable nevertheless.

“The Long, Cold Goodbye” by Holly Phillips is set on a planet (or perhaps in an alternate universe; it’s hard to say) whose northern hemisphere is trapped in an ice age threatening the humans living in the city. A mass exodus is in full swing as many try to catch the last airships out before the big freeze kills them all. In the midst of this chaos, a young woman seeks her friend/lover to try to convince him to leave with her. Holly Phillips is certainly a great writer and her prose is as strong as any fantasist working today. My only complaint about this story is that I found it difficult to get my mind around what was happening environmentally and why. A little more science and clarity would have made this story much better.

“Slow Stampede” by Sara Genge tells of the socio-economic conflict between three peoples on a swamp planet. The urban peoples cart their goods between cities on the backs of massive swamp elephants, while merfolk and raiders vie for the scraps they steal from these mighty caravans. Though more a fantasy than science fiction (there’s one reference to binoculars and one of a second sun), I found Genge’s setting quite interesting and would like to see the concept handled in longer form where the environment and characters could be developed further.

I’ll be honest: I’m not a fan of short-shorts. My opinion of them is that you either get the punch-line or you don’t. With Benjamin Crowell’s “Whatness,” I couldn’t get it. Here we have, according to the first line, two “orphaned awarenesses,” which I suspect are trying to figure each other out and why they are where they are. What happens after this, I simply couldn’t fathom.

The issue concludes with “Getting Real” by Harry Turtledove. The king of alternate history weaves a tale wherein the U.S. has been relegated to third-world status, its financial and military power ineffective against a Chinese juggernaut encircling the globe. One of the ways the Chinese keep the natives in line is through a virtual reality drug called “Real,” administered in small cardboard-like cubes through the use of avatars appearing to their victims out of nowhere. These so-called “Real” adventures are like games and, to the characters, they feel more real than their real lives. The Chinese are truly a superpower in this story, but be careful what you wish for: a drug to one country could very well become a drug to another… even its supplier. It’s a good, but not great, story, where the historical shift of global powers is far more interesting, in my view, than the VR elements.