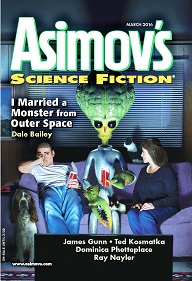

Asimov’s, March 2016

Asimov’s, March 2016

“The Bewilderness of Lions” by Ted Kosmatka

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

Ted Kosmatka’s “The Bewilderness of Lions” depicts a near-future in which data mining really can predict the future. The piece opens on our protagonist, learning lessons about life from observations in the backyard of her childhood home, then skips to a presidential election campaign meeting where she predicts disasters from patterns she divines from data. Back and forth: we see the youth that forms the protagonist, then the protagonist’s adult work. “The Bewilderness of Lions” depicts characters that ignore stereotypes as readily as they revel in them. An overbearing tall suited man in authority fires a (woman data mining savant) subordinate for truthfully answering a question put to them by their customer after being ordered to stay silent; a girl bullies her older brother; a politician makes a deal with the devil. The story’s disregard for some tropes enhances the effect when it adheres to some hoary old stereotype in others. The story’s willingness to depart from expectations provides the short climax’ punch: we really don’t know what the protagonist will do, given the stakes. And her history colors the stakes – all those flashbacks do more than explain the protagonist’s skills. The unexpected motive revealed in the last paragraphs gives the story – and the narrator – an unexpected depth I wouldn’t want to discuss for risk of spoiling her motive or her decision.

Dominica Phetteplace’s “Project Empathy” narrates the young woman Bel’s attempts to advance her life and career in a dismal future that parodies the worst of modern San Francisco when it doesn’t inspire horror. Bel is not, however, the narrator. In Project Empathy, gentrification is backed by a permit system to determine who’s allowed within the city and whether they may dwell there or only visit; a Border Guard patrols the city, backed with robots and drones to check IDs during overhead passes to verify everyone’s permits; deportation solves homelessness – at least within the city walls. Against this background, Bel uses her hostess job – which depends on leveraging her social status, as monitored by her employer, for marketing – to seek job security and opportunity by transferring from her small-town market built on high-school trends (from which she would age out of employability in two years) to the city location (where the age demographic creates the potential for long-term employment). There, increased job demands, a hard new alien school, unfamiliar social environment, dramatic income disparity, and looming sense of isolation and disillusionment begin grinding her from a confident teen to a fearful prole. Like a grim-future version of Dowton Abbey, Phetteplace’s world depicts the significant labor required to present what the more intensely consuming classes take for granted: high school tutors must be award-winning journalists; restaurant wait staff require Ph.D. education. Like so many protagonists who strike out to make it in the big city, Bel mistakes entertainment for documentary long enough to throw herself into the jaws of a machine lubricated by individual subjugation.

“Project Empathy” sketches class and isolation, privilege and desperation, and human lives hemmed in by corporate interests with access to information casual observers would have no idea has been collected. Initially, we see Bel depicted with clinical detachment, and it is hard to empathize with her – but Bel isn’t the narrator; the clinical view at the open perfectly suits the narrator’s initial observations. Phetteplace employs what must be my favorite use of first-person narration, which is to place in plain sight – every time the “I” appears – a reminder that we only know about the narrator what the narrator has bothered to mention. “Project Empathy” makes great use of the narrator’s reveal to wrap the story on a note that emphasizes the horror of the corporatist information economy. Phetteplace’s story is not only a fun read, it does what science fiction has always done at its best: to sketch a portrait that allows onlookers to see where the world could go, and to offer an opportunity for readers to consider whether it’s a world they’d want to live in – hopefully, in time to pull the brake.

Dale Bailey’s “I Married A Monster From Outer Space” opens like a first-person comedy in a Walmart where our narrator is unsurprised to see an alien shopping during the third shift. The narrator’s daily grinding misery, coupled with her stubborn insistence in offering aid and sympathy to the helpless, makes her easy to like. Her colloquial narrative voice doesn’t lampoon trailer park dwellers so much as add an ironically entertaining ho-hum veneer to the outrageous events. The same veneer has a very different impact when applied to facts the narrator relates about the conduct of her husband: it renders the events much darker and suggests the narrator is crushed by their weight, which cumulates with that of a society that continuously devalues and ignores her.

There’s nothing about the story’s plot or message that requires aliens. Adding an alien as scenery is, however, well-matched to the story’s theme of our opacity to onlookers, who see pictures from their own imaginations instead of who we really are. The harmless alien monster from the story’s opening line is a stark contrast with the men-are-from-Mars style alien monster represented by her mechanic husband. Whether the story’s heart-warming conclusion works for a reader will surely turn on the reader’s capacity to develop positive feelings about a relationship with someone capable of displaying the despicable behavior demonstrated by the narrator’s husband (readers sensitive to rape accounts and psychological abuse stand warned). Readers who loathe the narrator’s husband may be hard-pressed to believe the choice she makes, but the prospect of hope for her future offers what’s surely intended as a happy ending. The narrator’s insight into her husband’s own miseries and needs, and the emotional re-connection depicted in the wake of their shared misery, gives energy to a conclusion that readers might otherwise view as a missed-opportunity downbeat. The uplifting undercurrent in the narrator’s recognition of her husband’s positive (she may think “redeeming” even if readers doubt) characteristics feels like a sweet note in the otherwise largely sour flavor of her larger world. Bailey has given “I Married A Monster From Outer Space” a delightful narrative voice and peppered it with humorous exchanges too numerous to count the chuckles.

The Czech author Julie Nováková sets the first-person “The Ship Whisperer” in a science fiction universe in which computers capable of interstellar navigation possess an unintended degree of artificial intelligence, requiring specially skilled ship controllers to troubleshoot problems that require mind-to-mind contact. The story is “hard” SF: plot problem and its solution depend on science fiction elements. Big themes resonate: the humanity of Others, authority figures’ fear of the unknown, the value of sacrifice. For a short story, “The Ship Whisperer”’s social setting exhibits delightful complexity: inevitable tensions with nearby settlements with frightening alien practices; duty to the crew’s homeworld; on-ship politics and command structures and security protocols; the narrator’s only human ally is a scientist who operates on a wavelength unrelated to on-ship politics; even ships’ AIs have social interactions and priorities. Nováková’s marginalized protagonist sacrifices to prevent superiors’ cruel use of a newly-discovered technology, and lives with the consequences. Lots of word count delivers description and explanation rather than action or dialogue, but fans of hard SF will enjoy the tale Nováková spins in “The Ship Whisperer.”

Sunil Patel’s “A Partial List of Lists I Have Lost Over Time” is a comedy that takes the form of a series of to-do lists made by a basement-dwelling mad scientist with a proclivity for making lists. Or, made by his evil twin from another dimension. It’s hard to tell, with some of the lists. It’s not immediately obvious how a collection of lists would disclose a story, but each successive list communicates enough about the character’s identity, discoveries, and evolving plans that readers infer action that’s more entertaining to work out than to have described in detail. It’s not long, it’s a quick read, and it’s highly entertaining.

Ray Nayler’s “Do Not Forget Me” is a fantasy story-within-a-story set in the Middle East in the age of travel by horse. The story’s virtue is not its quick start: the outer layers of framing about the story consume three pages before we learn what the wanderer tells the poet who tells the narrator who tells his wife. The piece reflects an oral story-telling tradition that includes adding details about a story’s origin to increase listeners’ confidence in its truth. The multi-layered story design might be expected to have a story and a conclusion in each layer; since the framing layers’ narrators have at best nebulous scene goals, the real power in the layered design lies in allowing a theme to be repeated in each layer, to improve resonance with the reader by suggesting the idea is so universal each narrator shares it. The outermost layer’s conclusion is interesting: the reader cannot know whether the narrator’s wife is particularly wise or merely naïve, but there is no doubt her assessment what to do holds the most promise for the future. Nayler’s tale has a pleasant slow-burning feel, and its conclusion suggests that existential fear about the significance of one life in the span of eternity has a solution in enjoying the opportunities afforded while we remain alive.

James Gunn’s “New Earth” is a SF short story set on a colonization destination. Dialog infodump grates. (Mission leaders already know the mission’s limited headcount and the mission plan for frozen embryos, right? If facts need mention for readers, characters can think about how the discoveries impact them without improbably discussing them aloud.) Arrived on New Earth, the pace of mission progress is debated between the first two wakened crew: an enthusiastic optimist and a cautious skeptic. Since the story didn’t open as a comedy, it feels hard to accept that upon arrival the first two colonists would resort to waking a philosopher to adjudicate their unresolved dilemma whether to proceed immediately or wait to conduct safety analysis. And, yet the development feels like the opening line of a joke: a biologist, a pilot, and a philosopher are stranded on an island …. It is difficult to credit that something as long-planned as planetary colonization would fail to include planning to assess environmental safety, or to develop a path to effectively supporting the population the mission planners sent across the stars at such an expense. The pause for debate felt premature. I simply could not believe something so basic to a mission would go unplanned to such an extent that settlers would be put to gambling their lives on the happenchance their sacrifice might expose local risks in a way that would support survivors’ efforts to develop a coping strategy. The hard-to-credit conflict undermined the impact delivered by the philosopher’s climactic sacrifice. I really wanted to like this one, and would have accepted the slow open for a good payoff, but I could not believe in the conflict or its solution.

The narrator of R. Neube’s “A Little Bigotry” is a dismal-future SF that opens on a scrappy survivor approaching a dismal planetary system in the hope of eking out an existence someplace her criminal record might not follow her. She can’t find employment in the fields promised by the immigration pamphlets but finds, instead, the harsh oppressions of a gold-rush town magnified to planetary level: the aliens who run the planet’s mines won’t spend more than a couple years exploiting them before the whole operation will fold. And she still can’t get work. Her desperation evident, she receives (and doesn’t discard) work offers she finds offensive. The story’s word count mostly occurs over dinner where a “bug” alien veteran of the same war she fought for five years hires her to disabuse his textbook-educated children (adopted, because like her he was sterilized by radiation during the war) from a simplistic understanding of the war and obliviousness to the alien values and practices of humans. Rachel and the “bug” children learn about each other, and the distant economic reasons the war for which humans were hired as mercenaries originally erupted between the two nonhuman species who were its principals. “A Little Bigotry” describes alien propaganda and misinformation and educational practices and fears with the seeming objective of suggesting humans could make peace as easily with each other as with terrifying aliens if only they would sit down and talk, which may be a bit too much syrup for some readers. However, the tough narrator’s scrappy-survivor attitude and her unexpected takes-no-shit backstory make her sympathetic. The worldbuilding, especially the technological and social details, give the story a credible feel. The pace and timing of character and world backstory reveals create more tension and excitement than one would expect of a story related in dialogue over dinner. “A Little Bigotry” is a fun story about a down-on-her-luck badass who doesn’t give up, and recommended.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.