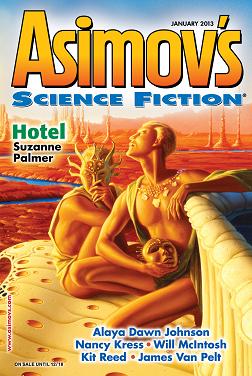

Asimov’s Science Fiction, January 2013

Asimov’s Science Fiction, January 2013

“They Shall Salt the Earth With Seeds of Glass” by Alaya Dawn Johnson

Reviewed by Michelle Ristuccia

“They Shall Salt the Earth With Seeds of Glass” by Alaya Dawn Johnson tells the story of two sisters, Tris and Libby, who leave the relative safety of their village in search of an illegal abortion, all under the oppression of a powerful alien invasion. We are introduced to the problem of Tris’ pregnancy in less than a page, yet that page also manages to give us a feel for the technology of the farming community and introduce us to the two main characters all in one go. From there, Libby, the narrator, deftly explains why her sister wants an abortion and why she supports that decision despite the odds stacked against them. It’s not an exaggeration to say that the sisters put the entire town at risk just by asking about the illegal medical procedure.

Their adventure away from home seems doomed from the start, so it is no surprise when an alien drone captures them and prepares to take them to a hospital-prison where Tris will be forced to carry the baby to term. Here is where the story truly shines no matter your personal belief about abortions, for in meeting the alien drone, we see a depiction of “otherness” that sets the spine tingling. First, these mysterious invaders are not even present in their physical bodies. In fact, their physical bodies, assuming they have them, have never been seen by any human who lived to tell about it. Secondly, the glassman goes on at length about “saving the pregnant one” and does not seem to understand its human prisoners in the least. We get the sense that the aliens’ needs and motivations are so different from our own that empathy between the species would be impossible, even if more was known about them. Their mysterious physical existence almost doesn’t matter except that it makes them harder to kill.

At the same time, this Otherness necessitates Libby and Tris’ escape attempt, because there can be no reasoning or negotiating with their captors, and only rumors can say what happens to the pregnant women who end up in their care. Luckily for Tris and Libby, they are helped by resistance fighters who know quite a bit about the drones’ weaknesses. The occurrence of the abortion itself is then greatly glossed over in favor of emphasis on the characters’ fight for freedom. The text leaves us with a view of the sisters heading back to their village, with the unanswered question of whether or not the village suffered for their defiance. This seemingly loose end is not a disappointment, though. The point of leaving off here is that Libby and Trish did the right thing in defying their alien leaders, and if any cost has been extracted for their bravery, it is on the glass heads of their oppressors. A captivating and well thought-out story, overall.

“The Family Rocket” by James Van Pelt is the narrative of a young man, Lorenzo, preparing to introduce his girlfriend to his eccentric Papa, yet we never see the actual introduction. The narrator’s description of his childhood is fairly straight forward. His family has always been poor, and his father is a dreamer who tries to instill in his children the desire to escape the ghetto and see Mars. After acquiring a broken down rocketship, Papa convinces the children that they lift off and visit Mars. It is only after they are adults that Lorenzo realizes that their Mars vacation was a fantasy.

From here, the narration breaks down as the story plays with the idea that fantasy can be just as important as reality. Lorenzo presents us with two versions of his girlfriend meeting Papa. In one, Papa has fixed the spaceship up and they blast off to Mars. In the other, they pretend to do so. The story wraps up with Lorenzo’s private declaration that he wishes to be as good of a father as Papa. The text hints heavily that, just as when Lorenzo was a child, the rocket is only scrap metal and no one has lifted off to Mars. Even so, I dislike the disseminating manner in which the story is told. It is one thing to have an unreliable narrator and another to have one who refuses to tell you the truth and, in fact, gives you multiple versions. Even knowing that Pelt’s use of this technique is directly related to the story’s theme, I’m left feeling unsatisfied.

“Mithridates, He Died Old” by Nancy Kress follows the internal revelations of a woman undergoing an experimental drug after a near-fatal car accident. The story explores the idea of the mind as a black box, showing us that even Margaret’s physician has no idea what the drug is doing to her. As Margaret makes difficult analytical connections between disparate life events, her physican can only see the apparent distress of her physical body, and so the drug trial is declared a failure.

As for what Margaret learns, Nancy Kress gives us a sympathetic character whose heart is a bit shriveled and dusty. Like any of us, Margaret has made decisions in her life based on false assumptions. Her prejudice happens to be against young people, which is unfortunate considering that she is a teacher of said youth. Her injuries and the drug give Maragret the opportunity to dig out the ageism that has taken root in her soul, but to do so she must recognize how her assumptions have negatively impacted others in her life. By the end, the reader has hope that Margaret will lead a better life, even if she can never truly repair some of her larger mistakes.

This is a fun story. I enjoyed the references to Phineas Gage, and other psychology references.

“Over There” by Will McIntosh relates the horrific results of a double-slit experiment that splits reality when it forces two opposing probabilities to manifest at the same time. After the split, the story is laid out in two columns that each follow a separate reality, both of which the characters are experiencing simultaneously. At first I thought that I would hate this, but as I read the tandem stories paragraph by paragraph, I fell in love with the studependous construction of the text, which is so well paced that you can read them without much chronological backtracking. Because the characters’ consciousnesses are experiencing both realities, the timelines affect each other in fascinating ways that ultimately contribute to several experimentors’ deaths as the rest of the world finds out who is to blame for their hellish new existence.

Readers who like puzzles will enjoy following the plot of “Over There.” Even for those who find their heads hurting from the attempt, the basic themes of desperation and forgiveness should lend you strength. I only wish there was a little more follow-through on the final fate of the characters and the rules of the split worlds. Reality is attempting to correct itself by reducing itself back to one manifestation, but this process is neither quick nor painless. Some of the characters are left as frozen statues in one reality and broken minds in the other, and Nathan doesn’t get to figure out a solution before the story ends. The ending is left open, but still does its job well as it shows Nathan coming to an important decision. I can see this story being part of a set of stories that bring the reader through to the destruction of one or both worlds.

“The Legend of Troop 13” by Kit Reed shows us glimpses of a girlscout troup that runs away from civilized life to live out their Peter Pan-esque fantasies at the top of a mountain where a giant telescope happens to be. The text alternates between perspectives of the troop members and perspectives of the tourists and their tour guide. Unreasonably, the married men on the tour expect to find and seduce naive, young adult girlscouts, much to the disgust of their wives and the tour guide. The scouts, for their part, have no qualms about killing any tourists who approach them. In fact, each change in perspective seems to either mention a past death of a scout or imply past tragedies involving tourists. Finally, one of the tourists escapes the reluctantly watchful eye of the tour guide, and the ensuing confrontation brings about plenty of the promised death, along with the revelation that the young scouts aren’t what they appear to be.

I was never quite sure whether the tone of this story was supposed to come off more as horror or as humor. The main plot points work either way, but the text never quite resonated with me. Much of the text was dedicated to describing how piggish the tourists are. I’m either not cynical enough about financially successful men or not afraid enough of who the scouts turn out to be, or possibly both.

“Hotel” by Suzanne Palmer is a comedy set in a Martian hotel that must weather deadly politics in order to remain a place of freedom and neutrality. Translation: there are a lot of secret agents who are all trying to kill each other. The story opens with a new arrival at the hotel – “Smith” – who makes it clear that he is desperate to rent a room. As the clerk checks him in, Smith must agree to a number of rules that establish the humorous tone and introduce the science fiction setting. The Hotel’s restrictions on weaponry and technology prove to be a hassle for the many characters who wish to kill other hotel residents, ensuring that the unfolding comedy comes apart one knife at a time instead of blowing up all at once.

After Smith’s arrival comes Martian government officials who demand to search the hotel. Despite threats and the flashing of guns, the hotel staff give them the same treatment as they gave Mr. Smith, who, by the way, is the third “Smith” on their roster. The Martian officials decide to check into the hotel to seek out their objective in a more-or-less law abiding fashion. These new arrivals are the tipping point that causes several of the residents to attempt to murder each other, all for mysterious reasons. It is only once half the hotel is either dead or tied up that we begin to learn some of the conflicting objectives that bounce the plot along.

I highly recommend “Hotel” for several reasons. The plethora of details makes “Hotel” science fiction through and through, with Mars, aliens, and A.I.s. The comedic tone is pervasive without interrupting the action-driven plot. Palmer also serves the reader plenty of fun misdirection along with her tip-of-the-iceberg character development and backstory. The happy ending is as tidy as the beginning is intriguing. “Hotel” definitely holds its weight in this issue of Asimov’s.

Michelle Ristuccia enjoys slowing down time in the middle of the night to read and review speculative fiction, because sleeping offspring are the best inspiration and motivation. You can find out more about her other writing projects and geeky obsessions by visiting her blog.