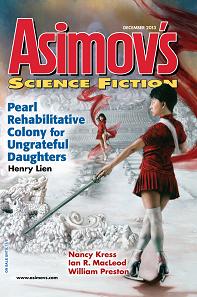

Asimov’s, December 2013

Asimov’s, December 2013

Reviewed by Louis West

In Henry Lien’s “Pearl Rehabilitative Colony for Ungrateful Daughters,” 18th century Qing Chinese traditional expectations for girl children clashes with the equivalent of 21st century street gymnast independent-mindedness, except this gymnast performs Wu-Liu martial arts on ice-skates, using an urban setting as her playground. Suki, who prefers to be called “Her Grace, Radiant Goddess Princess Suki,” has been sent by her disappointed parents to the Pearl Rehab colony to learn proper, subservient daughter behavior and master the skills to make it into the Pearl Opera Academy. Seriously stuck-up, everything is only about her and her needs. However, to graduate in first place, she must find a way to work with her hated rival to beat the best sent against them. Unfortunately, as much as I relished the unique physical and cultural setting of this story, Suki never changes. Her heart hardens due to her experiences, and she remains true to her original goal to make it into the Opera Academy regardless of the cost. “Piss me off to death,” as she would say.

“Vox ex Machina,” by William Preston, is a surrealistic tale about a flight attendant desperately trying to avoid the responsibilities of a life gone to hell—husband left her for another, the loneliness of her erratic work, and the question of what to do with an android head she’d whisked off the plane after finding it left in an overhead storage bin. Through scene after scene she swims through daily life, avoiding the issue of the head, even though she dreams of it in her sleep. She tries to talk with the head, but its replies are as elusively cryptic as the purpose of her life. In the end, a friend of hers puts it in a box on a bridge for the police to find and, hopefully, return to the owners of the rest of the android. But that doesn’t turn out well either. I simply could not find anything to appreciate about this story. It dragged and wandered, ending up as empty as the protagonist.

In Ian R. MacLeod’s “Entangled,” the world is struggling out of collapse caused by the rapid spread of a virus that mentally “entangles” people into a gestalt, creating a new, scary, type of person. But Martha is different. During a long-ago break-in at her father’s house, her brother had been killed and she’d been shot in the head. Her doctor-father healed her, using new nanotech to create an artificial substitute for her damaged brain, expending his own life while providing her with full-time rehabilitative care. Now, more construct than human, she’s immune to the entangle virus, “mindblind” and alone. She knows who’s responsible for the break-in and shooting—an old boyfriend of hers. After all these years, she’s finally found him again and wants answers. Except, what she learns completely unravels her sense of self and reality. This is an interesting story of self-discovery that meanders through the morass of Martha’s life and is mirrored by humanity’s own efforts to find new purpose and direction.

“Dignity,” by Jay O’Connell, portrays Melissa’s struggles to turn a homeless girl, Lena, into her own servant against the wishes of her disapproving father who thinks Lena is nothing more than junk genome, a “hopeless one.” Melissa’s family is very rich, their estate huge and heavily protected, their servants conditioned to make sure they’re “safe.” She offers to pay for Lena’s conditioning out of her own allowance, but her father forces her to send Lena away. Undaunted, she remembers that her father had promised she could design any augmented puppy she wanted for her birthday. Drawing upon her 2nd grade contract law class, she comes upon a plan to foil both her parents because “Lena is far better to own than any puppy could ever be.” A fun story about the enormous capability some kids have to outsmart their parents specifically and adults in general. And 2nd grade contract law classes? Now that’s scary.

In Timons Esaias’ “The Fitter,” Miss Douglas, owner of Randi’s Bustique Boutique, hates aliens. To her chagrin she finds herself hiring a Thaliamajoram, a giant sea anemone-like alien, because it seems so good at getting customers to buy her lingerie products. Thalia aliens are all the rage. Although lacking any particular talent or transferable skill, they take directions well and have become successful both in Hollywood and Madison Avenue. Miss Douglas’ business booms. Celebrities come to shop there. The Thalia she hired masters the intricacies of women’s lingerie fashions and everyone at the shop does fabulously well. “Out-of-towner” does good, and the tabloids fail to find any underlying scandal. A cute satire on the fashion industry.

“Bloom,” by Gregory Norman Bossert, concerns three people who find that they’ve stumbled into the middle of a Bloom in the dark of night on the alien planet on which they’ve been stationed. A Bloom: A Circle of Life, a colony of mycorrhizal organisms that consumes whatever stumbles into them by ripping it apart in an orgasmic feeding frenzy. Except when it’s quiescent in the dark. The sun to this system will rise in a few hours. However, since all three people have broken through the crust of the Bloom when they stumbled into it, any movement could trigger the feeding phase. So they stand in place, fighting their fears, arguing, pleading with each other and themselves about possible rescue and how they’d ended up here. Ben and Andrea had snuck out for sex under an alien sky and just wanted to escape. In contrast, Ki had survived an encounter with a Bloom before and had been transformed into something else. Every night since, she had wandered the landscape both cursing the Blooms and longing for one in particular. Perhaps tonight she will find the release she seeks.

This story is full of raw fear, bravado, controlled freak and cold logic. Imagine knowing you’re going to die a hard, horrible death with the coming of sunrise but you must wait, motionless for hours, staring at the means of your death in the faint hope that rescue will come. Masterful. Thanks, Greg.

In R. Neube’s “Grainers,” life on an alien grain ship converted to house 21,000 refugees from a nuked Earth is this side of hell. Handy is the ship’s handyperson. Even though he had a Ph.D. in xenotech, he’d returned to this ship as the only home where he’d not been derided for being born on one. All the equipment essential to running the ship and maintaining life support is barely functioning with repairs cobbled on top of repairs. But Handy has a detailed plan to help the ship resolve its numerous problems, and it involves pulling off a dangerous con against the very Fiver military that would just as soon blow them out of space if it weren’t for the Refuge Accords. The story deftly flips back and forth between Handy’s point of view, as his plan unfolds, and the Tech Seven sent by the warship in response to their mayday, with each party thinking they have the upper hand on the other. Nicely done. A good read.

Megan, in Nancy Kress’ “Frog Watch,” is crazy, the “terrible kind” that descended upon her after Jason, her cop-husband, was killed in the line of duty. Escape beckons in the form of a ramshackle, creepy house on the edge of a Georgian wetlands preserve. No internet. One distant and aloof neighbor—Surly Sally, Megan calls her. Alone except for her daily census of frogs, an activity her husband had once pursued with her, forms the link to the life she’d once had. Her weekly frog census reports prove at odds with everywhere else; hers show an explosion in numbers without deformities. Now she has to walk the swamp to retest her counts. A seemingly idiot-savant 12-year-old boy, Silas, shows up on her front porch one day and invites himself in, then falls asleep, gone before the morning. Soon thereafter, Sally stops by, looking for the boy. Silas and Sally seem barely human to Megan, concluding they’re aliens when they destroy each other with blue laser beams. Shortly thereafter she discovers a mass of alien amphibian eggs escaping from Sally’s place into the swamp. As a new mother-to-be, Megan resolves to protect her world from whatever experiments the two aliens left behind. A gritty, satisfying read.