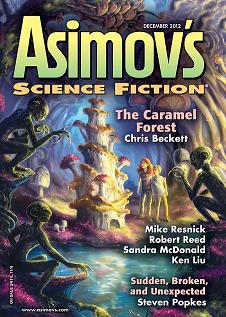

Asimov’s, December 2012

Asimov’s, December 2012

“Sudden, Broken, and Unexpected” by Steven Popkes

Reviewed by Louis West

This issue of Asimov’s contains a broad collection of SF and speculative fiction tales. Although I enjoyed only some, I still recommend reading them all, for it is through each reader’s viewpoint that the true quality of each story emerges.

“Sudden, Broken, and Unexpected,” by Steven Popkes, starts in a rush, “like a volcano…or a magnificent catastrophe.” This story is densely packed with intricate plots and character conflict. It’s liberally sprinkled with details about music theory, computer architecture, behavioral theory, plus debates about what constitutes creative artistry and independent consciousness, all spiced with gritty tension between Jacob and his ex-girlfriend, Rose. Jacob, an exceptional but burnt-out musician, rails at his continued infatuation with Rose, especially when she shows up after a 12 year absence to offer him new work. Except his client is Dot, a divaloid, an electronic construct who is also a world-class rock star, facts that Jacob finds impossible to reconcile. But working together with Rose and Dot changes everything, and everybody, in ways Jacob could never have imagined. A brilliant piece. The genius of the author’s musical experience effortlessly channels through Jacob, and the increasingly emotion-laden interaction between Jacob and Dot sometimes gets very intense. A must read.

Ken Liu’s “The Waves” poses an intriguing question—although we and our creation myths may define each other, is there a point at which we become the myth? Maggie Chao is one of Earth’s first interstellar colonists, and an immortal. Her story traces waves of change that humankind might well have to master, as they expand into space. A mortal colonist on a slow-ship has a much different view towards family and children than does an immortal. New planets may best be colonized, not by terraforming, but by adapting settler genetics to the demands of the planet. Technology might make the idea of separate human individuals obsolete. Cyborg augments can link us mentally. Humans may even discover the hive-colony advantages of shared existence as a group singularity. But, at what point do we become powerful enough to become the creator, not just the created? A thoughtful piece that took several readings before I’d gleaned everything from its densely packed collection of ideas.

“The Caramel Forest,” by Chris Beckett, traces Cassie’s struggles to come to terms with her new, alien homeworld and its seemingly mindless indigenous creatures that speak in her mind. These “goblins” frighten the adults, and many settlers kill them without compunction. But Cassie is true to the old adage that children’s minds are more plastic, more flexible at comprehending new concepts. Whether or not she can apply that understanding to making either her life or the lives of the natives better, the story does not resolve. Regretfully, I found the story slow and the ending unsatisfactory.

Mike Resnick’s “The Wizard of West 34th Street” is seriously entertaining, especially in light of the Wall Street debacles of 2008. Who knew that the real expertise lay in the hands of a singularly unprepossessing man, and too bad all those financial “experts” didn’t consult with him. With all gifts, though, there is a price, and Jacob, the Wiz’s only friend, learns this the way most of us do, the hard way. Although I surmised early on where this story might lead, I still enjoyed the telling and the sobering results.

“The Black Feminist’s Guide to Science Fiction Film Editing,” by Sandra McDonald, explores a post-global warming world where batteries of editors work to reconstruct films in order to correct the misogynistic treatment of women by a male-dominated industry. While I understand the on-going struggle of women for equality, especially given that gender bias is practically hard-coded into many religions of the world, as a man I can’t possibly grasp the raw angst of that struggle. With that caveat in mind, this story didn’t really grab my interest until Minervadiane and Samueldarrin, two diametrically opposed film editors, butt heads over possession of a 1970s Outlaw of Mars SF classic, The Ginger Star. For me, their love-hate relationship embodies the true nature of the chaotic struggle for equality that has played out across the millennia in many cultures and walks of life.

Robert Reed’s “The Pipes of Pan” asks whether humankind truly deserves a separate genus designation or are we just one more species of ape. For Lawrence, an up and coming biologist, the answer is an obvious “no” and reclassifying humans as Pan sapiens foetus should help us embrace our beast nature and reject mankind’s tendency towards violence. But, ultimately, what’s in a name? I did not find it credible the ease with which Lawrence was able to convince the world to change humankind’s classification. Although, when global warming plays havoc with global weather and economies, it was obvious to me what the results would be. The story’s POV is unique—Lawrence views his behavior, and all those around him, as if everyone is a chimp. But the conclusion was unsatisfactory.