“A Large Bucket, and Accidental Godlike Mastery of Spacetime” by Benjamin Crowell

“A Large Bucket, and Accidental Godlike Mastery of Spacetime” by Benjamin Crowell

“Some Like It Hot” by Brian Stableford

“A Lovely Little Christmas Fire” by Jeff Carlson

“As Women Fight” by Sara Genge

“Animus Rights” by John Shirley

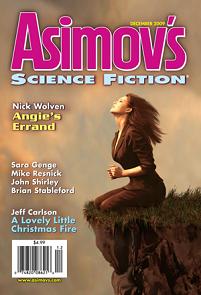

“Angie’s Errand” by Nick Wolven

“Leaving the Station” by Jim Aikin

“The Bride of Frankenstein” by Mike Resnick

Reviewed by Steve Fahnestalk

As readers of my reviews might have noticed, I like looking for themes in magazine issues; there’s a very obvious one in the last Asimov’s of 2009: women in power. Or women of power. Or empowered women. Of course, the PC view is that as a male (and an older Caucasian male at that) I’m not entitled to talk about issues of gender, race, age and who knows? maybe species as well! But how can I not, when it’s in your face here? (Not speciesism, ageism or racism this time, though. But I’d love to get into that argument when it’s time.)

Growing up, it never occurred to me that there could be any argument about whether women could (or would) write SF as well as men. My SF role models included, besides the usual male biggies, Catherine L. Moore, Judith Merril, Marion Zimmer Bradley and, of course, the most notable female SF writer who used a man’s name at that time, Andre (Alice Mary) Norton. And there were the female fantasy writers, too… so the idea that men were somehow better suited to it, or more qualified for it, never took root in my mind. And that goes for female characters, in spite of the fact that 90% (I’m guessing) of all SF protagonists are men.

I’m all for empowerment, whether it be males or females. I’m all for strong female characters. I’m for strong characters anyway, as long as that strength is not at the expense of other characters; in other words, I dislike bullies of any gender. Fortunately, most of the female leads in these stories are as strong as you could wish, with an appealing inner strength in many cases. Let’s get into the lead novelette by Benjamin Crowell, “A Large Bucket, and Accidental Godlike Mastery of Spacetime” which has as its protagonist one Sidibé Traoré, an American astronaut who’s applied to be a representative to the Galactic Civilization (or GalCiv), even though that means she’ll spend the rest of her life as the sole human aboard a city-sized “Bus” that loops around the galaxy at near-relativistic speeds picking up “people” as it goes; it also means that to get on the bus, she’s been sliced and diced, Julienne French-cut, and reassembled like Frankenstein’s monster. (For that reason alone, most of the applicants for the position on Earth have changed their minds and dropped out, which is why Sidibé got the job.)

Sidibé is half-American, half-Mali, and has no family left in the US except for the astronaut corps, so she’s glad to go. Who (or what) she meets there, and how she figures out (partly by sheer happenstance) what to do and what the cultural assumptions might be where she is, makes up the rest of the story. I found it a hoot, and liked the nod to the Wizard of Oz (in the persona of The Gump). I won’t tell you much more about it, as reading it was half the fun. Oh, and in case you’re interested, she only achieves God-like Mastery in her local space-time continuum.

“Some Like It Hot” by Brian Stableford was not as enjoyable for me, although like all Stableford’s fiction, it was well written. As SF readers, we’re supposed to be able to cope with any kind of speculation, whether it be alien life forms, usable nanotechnology, time travel, what life on another planet can be like, etc. Where this story breaks for me is that I’m not sure Stableford’s rehashing of global warming is, in fact, speculation. In this story, it’s called “the Carbon Crisis,” or “CC”—and I get the feeling he’s swallowed the whole man-made global warming theory hook, line and poisonous heavy-metal sinker. Whereas in my mind, the man-made portion of it is still very much in question. Which means I’m not a disinterested observer, and that bugs me. I like to be able to take a neutral viewpoint to begin with.

Phrases like “everyone knew that [snow] was soon to become extinct”, coupled with the idea that the New Agricultural Revolution would make Kiruna, Sweden, part of a new farm belt for the world imply that we are already in an irreversible decline due to GW (or CC, if you prefer). The story centers around a young woman named Gerda, who grows up wanting to accelerate climate change to make a warm Gaia rather than attempting to recapture the bad old cool planet, for reasons that are at once ecological, political, economic and sociological. Her solution is ingenious (involving bio-electrical neo-cycads), but her conclusions, and my feeling that the author shares them, don’t really work for me. I don’t want to live on top of a swamp, thank you. Call me a reactionary, if you want.

But the writing is good, and the characters are well delineated. It’s just the story that puts me off.

“A Lovely Little Christmas Fire” by Jeff Carlson tells a story about Julie Beauchain, from Montana’s Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, who’s on a bug hunt in Missoula. The bugs referred to are a new strain of termites (created in a lab) that are on a rampage. The termites were created using genes from a particular type of pine rust; that, coupled with the fact that they were desert termites, was supposed to tie them to the rust as a food supply and thereby ensure that they died out after eliminating the rust which was “decimating” Montana’s Christmas tree supply. (Obviously, the author doesn’t know the meaning of “decimate.”)

But as Jurassic Park’s Dr. Malcolm says, nature won’t be contained—“Nature will find a way”—and the termites (“machos”— H. aureus machovsky) are running wild. And there’s a possible “internal terrorist” issue, which brings DHS into the picture. If not a terrorist, Julie suspects a saboteur, someone who’s trying to eliminate the competition by planting new colonies of machos. Julie is assisted by her boyfriend, who also works for the Department.

The story gets a little wild in the middle, involving possible government corruption, the aforementioned saboteur, maybe some “Men In Black” action, but all levels out at the end which, in spite of all the excitement, falls a little flat for me. But still a worthwhile read. (And if you’re keeping track, this is three strong female protagonists in a row.)

“As Women Fight” by Sara Genge is the only story in this issue actually written by a woman, and the unusual thing about this story is that the protagonist is a male who used to be a woman. The whole male/female thing on this particular planet is unusual in that the children are androgynes, with both sets of genitals, and only after their first period are they able to get an erection (usually); later they settle into one gender and (apparently) the other set of genitals goes dormant or disappears. (In the South, men and women are born as such and remain what they were born; in the frozen North, there is an annual Fight which determines what gender they are in a relationship. It doesn’t explain what happens to people who aren’t in a relationship. After the Fight, the winner determines who inhabits which body, and many swap bodies every year.

Men are stolid, unimaginative: they are the hunter/gatherers. They are slow, where women, the childbearers, the nurturers, the homemakers, are fast. Merthe’s wife, Ita, has beaten him five years in a row, sentencing him to the male body. He hasn’t divorced Ita, though, like his friend Samo might do to his wife. He just resolves to win this year’s Fight.

Because of speed and agility, women Fight differently than do men; men depend on strength to withstand the blows that come “quicker than the eye can see”; but a man like Merthe is not resigned to being a man forever. He has plans for after the next Fight. Plans that may not include Ita, and might include Samo’s wife.

At first I thought this was another take on LeGuin’s The Left Hand of Darkness; after rereading a couple of times, I had to rethink this idea. Because men and women fight differently on this planet, it’s a clue to how men and women are different. (Spoiler alert: the next sentence gives away a key plot element). Merthe wins his fight by not being stolid and unmoving; he wins by fighting as women fight (like Ali—floating like a butterfly). This is key in both the story and his relationship with Ita. At first I found the ending unsatisfying, but after a couple of rereads I kind of liked it. It grew naturally from the story and fulfilled all the story’s conditions.

Can I say that this story’s protagonist was a strong woman? Well, sort of. Merthe used to be a woman, and fought as women fight. The story is thought-provoking, for sure.

“Animus Rights” by John Shirley is not really a new story; it’s a retelling, in some ways, of the old “we are puppets” idea—that humanity’s wars are being prompted and fed by some external source. The protagonist here is a definite male protagonist, called “Animus”—his adversary is another, called “Adversary”—and they fight through the years and centuries in a never-ending battle, inhabiting one body after another in one conflict after another. Animus is a “Conflict Artist”—one who uses the conflict as his canvas, and paints his art with the broken bodies of humans as brushes. Besides, it’s a fun game—nobody actually gets hurt except humans.

But there is another player, a female named “Anima”—whose aim is to disrupt the game and make both antagonists see their tools as living, breathing, hurting beings. How and whether she attains her aims, is the upshot of the story.

This story unfolds as it should, but because there’s nothing new in it, I wasn’t greatly affected by it one way or another. The detail is good; Shirley has obviously done his homework on the periods mentioned. But perhaps because the protagonists are revealed to be nonhuman early on, the story didn’t really involve me that much, which is the kiss of death for fiction, in my opinion. Good fiction should involve the reader and arouse some kind of emotion, even if it’s to piss off the reader. This one didn’t.

“Angie’s Errand” by Nick Wolven fell apart for me almost from the beginning. It features a female protagonist who is not strong by nature, but by the end of the story, has become strong because the author tells us she is. Sort of “I am Woman, hear me roar.” That’s not my main problem with it, however; neither the setup nor the setting makes any sense whatsoever.

Look here: the story takes place in the near future, after a “Crisis” which apparently involved bombs, riots, purges and pogroms. Civilization, we’re told, has fallen apart. Yet this young woman, Angie, lives with her several younger siblings alone in an older frame house on the outskirts of a small Connecticut town that has escaped all the above. But because of the Crisis, her mother’s beautiful civilization has vanished, and women have become playthings and subjects of us brute men. “…every woman Angie knew had seized one man for her own, latching herself to a set of broad shoulders, a deep voice, as hastily and with as much instinctive pragmatism as she might have tied a house key to her wrist.”

Angie is young enough, though she despises having to do so, to find a young, brawny set of shoulders for herself, because she fears what might come out of the forest near their home; not for herself, but for the kids. So she sets out to find a high-school male friend who had made overtures to her then, years ago, and might still be amenable to being that stalwart she needs to keep the shadows at bay.

Psychologically, it makes a kind of sense, and heaven knows that if the civilization we know did fall apart, brute strength might be the determining factor in how you live your life; but I can’t believe in the post-Crisis civilization. In this small town, many ride horses, many ride bicycles, and yet there is a Market Day every second Wednesday, where “men in plaid shirts” unload “big trailer-trucks from Torrington” and pass the goods to tables which are surrounded by crowds of shouting people with raised fists.

Okay, who provides the goods? Where does the gas for these trailer-trucks come from? What is exchanged for these goods? Where did all the bicycles come from? Angie has “starving cheeks”—yet many of the men who crowd the town’s bar (moonshine and fried potatoes) manage to “stay fat in these lean times”… really? The whole setting is incoherent. Which makes Angie’s story unbelievable.

Where are the strong women who make their way in this post-Crisis world? Are there none? What about lesbians? Are they going to hitch their wagons to male stars? Why would they if there’s lots of goods and gas and (apparently) free distribution. Heck, why would any woman? In the absence of any justification for Angie’s dilemma, the story falls apart. Big time. I can’t in good conscience recommend this story to readers.

The penultimate story in this issue is “Leaving the Station” by Jim Aikin. Joan has turned forty, and has just inherited her uncle’s antiques store, which is fortunate, because as a programmer, her job has recently disappeared. (As did her severance money.) As a child, Joan saw ghosts, but wasn’t able to do it on command, so her parents never got rich from séances. After the séance business died (so to speak), Joan’s ability to spot the deceased eventually dwindled away as well.

But the antique store she has inherited is not full of priceless antiques; in fact, Joan characterizes it as “stacks of useless junk”—nevertheless, it brings in a small but steady income. Which allows her to take the occasional trip to San Francisco or Tahoe (it’s never actually stated, but it appears she and the store are somewhere in the East Bay area). The store used to be an actual train station, but that was somewhere in the dim past; it’s been an antique store for many years.

All is well until Joan’s ghosts begin appearing, one at a time, as they used to do when she was a child. Eventually, the fact that the store used to be a station comes into play, as do the ghosts; when one ghost leaves behind an actual, physical purse with a postcard inside, Joan’s life becomes easier. How Joan deals with her ghosts and reconciles herself to life as an antique store owner are the crux of this story; I don’t have a problem with any of that.

Except—the whole antique store setup is so old (remember “Shottle Bop”?) and has been done so many times; the only new part here is the ghosts as a mechanism for delivering goodies. The tie-in with the gramophone and “King Porter Stomp” is good, but still… nothing new here, really. And the whole business with the stamp—as a U.S. stamp collector, I’d dearly love to know what 3 cent stamp (used) is worth enough money to “pay [back] taxes and replace her [ancient] Geo with a new Civic”—really! It’s a nice enough story, but kind of blah.

And to tie everything up in a neat bow, we can always call on Mike. “The Bride of Frankenstein” by Mike Resnick takes a familiar tale and turns it on its ear, rather differently than did Mel Brooks. This Bride is the bride of Victor Frankenstein, not the creature’s bride. And rather early on in her marriage she realizes that being a Baroness isn’t necessarily all it’s cracked up to be.

She has the money, he has the title; it seems a fair trade, but the crumbling old stone castle has no central heating, no electricity, no amenities whatsoever, and all Victor wants to spend money on is experiments. Actually, she does remind me of Madeline Kahn’s character (Elizabeth) in Young Frankenstein, come to think of it.

Eventually, though our Bride ends up on the side of her husband, and the Frankenstein family becomes a family in fact as well as name, all four of them with a fifth to come. The fun in this story, and it is fun, comes from watching the protagonist’s character change and grow, as we all know the basic story of Victor and his creation. (In case you’re interested, the four are Victor, his Bride [never named, but I believe her to be Elizabeth], Igor and the creature.) The fifth will be “The Bride of Frankenstein”—because half the world thinks Frankenstein is the creature’s name, of course. Good story, and good ending. And yet another strong female protagonist.

Last issue I mentioned editing—at the end of this story there’s a blurb for the January issue of Asimov’s, and smack dab at the end of it is this: “Look for our December issue on sale at your newsstand on November 10, 2009.” Again I ask, what happened to copyediting?

Altogether, I feel positive about this issue of Asimov’s, although I didn’t care for the Stableford story or the Wolven story, and felt the Shirley story and the Aiken story were weak. Read the issue and see if you agree with me.