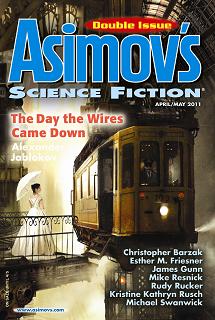

Asimov’s, April/May 2011

Asimov’s, April/May 2011

“The Day the Wires Came Down” by Alexander Jablokov

“Clockworks” by William Preston

“A Response From EST17” by Tom Purdom

“Becalmed” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

“An Empty House with Many Doors” by Michael Swanwick

“The Homecoming” by Mike Resnick

“North Shore Friday” by Nick Mamatas

“The Fnoor Hen” by Rudy Rucker

“Smoke City” by Christopher Barzak

“The One That Got Away” by Esther M Friesner

“The Flow and Dream” by Jack Skillingstead

Reviewed by Indrapramit Das

A double issue, with a solid set of stories, some of which venture into novella length.

The cover story, Alexander Jablokov’s “The Day the Wires Came Down,” holds plenty of interest as a partially successful piece of world-building, and rather less so as a story, or, as it were, an entire tangle of stories unwisely stuffed into one. The narrative follows Arabella and Andrew, twins, on an adventure exploring the byways of a cable-car transport system that connects the rooftops of their city, on the day the system is being shut down and dismantled. On the way, they become involved in a search for answers involving an antique, the history of the “telpher lines” and the company wars that plagued their early days (leading to their de-privatization), as well as a helpful “telpherman” with a penchant for collecting pigeon eggs.

The city itself, and its implied history, is very interesting—and Jablokov establishes an uncanny sense of atmosphere and nostalgia, easing the reader into Arabella’s bittersweet realization that everything is changing, both for the city and herself (she is leaving home for college). However, the twins’ chase for clues to the history of the antique they get their hands on for their father failed to hold my interest, especially because it leads to half the story being told in tedious expository infodumps delivered by Andrew. I was interested in the characters of the twins and their relationship to this elegantly sketched city (which resembles a western urban space of the early twentieth century, but with elements pulled from various eras), but Jablokov unfortunately devotes most of the story to telling his world’s (potentially involving) history in reams of dialogue.

Still, a story worth reading for its compelling speculative urban portrait.

William Preston’s “Clockworks” is an intriguing piece, told from the first-person viewpoint of Simon Lukic, also known as Dr. Blacklight, an archetypal villainous scientist (who, among other things, did research for the Nazis). Lukic finds himself abducted by an archetypal superhero, ‘healed’ of his earlier tendencies by the latter. While both the characters are human beings with no ‘superpowers,’ the parallels to the dual archetype of supervillain-superhero are clear. The catch is Lukic’s amnesia, brought on by the procedure that eradicated his antisocial bent. This becomes an obstacle, as his unnamed abductor is assembling a team to find the secret project Lukic was working on before he was abducted.

The now remorseful Lukic thus becomes a member of a team of ‘specialists’ out to save the world from the fantastical threat Dr. Blacklight set into motion; a familiar scenario made unfamiliar by both the viewpoint and the telling, which is grounded by its sense of time (the 1950s) and place. The narrative tells it straight, giving us a ground-level look at a traditionally fantastical pulp story that belongs in garish, dated comic-book panels from the 50s, but is here told in lucid prose that is, if not exactly ‘literary,’ introspective and reflective.

The enigmatic ‘superhero’ at the middle of it becomes a mysterious foil for the reformed Dr. Blacklight to reflect on his now shattered identity. The story is a curious mix of genres tempered by a certain ‘realism,’ such as when the team stops to have dinner at one of the team’s sister’s home in Chicago, leading to a scene of rich mundanity, which has the sister’s husband comment: “Given what I hear tell about you, I have to express some surprise that you’re breaking bread with us. Don’t you have some kind of secret base in every city?”

A good, well-written story.

Tom Purdom’s “A Response From EST17” is an ambitious, effective work of anthropological science-fiction detailing the ‘cold war’ between two competing human exploration collectives (composed of AIs and emergent technology with a remote-link to Earth) examining an extrasolar planet (the eponymous EST17). Their conflict catches the attention of the planet’s inhabitants, and triggers the potential for a massive socio-cultural event when one of the more socially aberrant residents of EST17 ignores normal procedure for visitations and makes contact with one of the collectives.

The story focuses on the humanoid inhabitants of EST17, who are plunged into a conflict of their own as they find themselves on the edge of a huge cultural revolution after centuries of unchanging utopian calm. It becomes clear that the outcome of these conflicts will decide the course of human history as well, for reasons that are best read in the story itself.

The story deals with events on a large scale, covering a lot of time and history with ease and skill (the inhabitants of EST17 are pretty much immortal, and spend decades in hibernation, and the two exploratory collectives’ communications with Earth take place on a similar timescale due to the latency of light-years), somehow managing to remain cohesive in its exploration of how cultures affect each other, and how delicate the balance in which they all exist. An intelligent, insightful piece of science-fiction.

Kristine Kathryn Rusch’s “Becalmed” follows Mae, the linguist of the Iviore, a starship “becalmed” in foldspace, while she is investigated for possibly endangering a diplomatic expedition to the planet Ukhanda, of which she was one of three survivors (out of 27). The story is told in flashbacks as Mae begins to retrieve her memories of what happened on the planet (indeed, she’s the second amnesiac in the issue). The nifty spacefaring spin on the old nautical term turns out to be of less consequence to the story (except as a metaphor for the character’s state of mind, perhaps) than the culture clash that happens on Ukhanda, where Mae finds herself struggling to navigate the cultural mores and language of the violent Quurzod.

Like Jablokov’s story, this is a story with promise that gets mired in too much exposition—this time delivered in large swathes of flashbacks in narrative time instead of scenic time, making a lot of what happens in the story feel rushed over. The story deals with Mae’s coming to terms with her own guilt (much like Preston’s Lukic character) at what happened on Ukhanda, but I found Rusch’s explorations of Quurzod culture and life on Ukhanda more interesting than Mae’s repetitive mental struggles while confined on the Iviore. A story more admirable for its ideas (about the importance of language, the dangers of cultural exceptionalism and the subjectivity of morality) than its execution.

Michael Swanwick’s “An Empty House with Many Doors” is a short piece about a man grieving for his dead wife, and seeing something he shouldn’t, leading to a more unusual confrontation of the realities of the loss than he might have expected. To tell any more would be to spoil the already short story. Suffice to say that this is a very familiar plot. I was turned off by the excess of the narrator’s grief right from the beginning, seeing as how its unearned (the reader doesn’t know his late wife in any way), but the story did win me over somewhat by the end because of its heartfelt reflection on loss and its relation to common science-fictional ideas.

Mike Resnick’s “The Homecoming” tells the story of a son returning home after a long absence to a resentful father and a mother in the grip of dementia, the science-fictional twist being that the son, Philip, moved to a planet light-years away, and now wears an alien body adapted to life there. An effective, and emotionally rewarding meeting of intimate literary themes (estranged sons and fathers, the toll of having a partner or parent with a debilitating disorder) and broad, science-fictional ideas and imagery (body-switching, interstellar colonization, the cosmic wonder of alien vistas with talking plants and crystal mountains). The father isn’t the most subtle of narrators, which for all his resentment made me ache for a more thorny or visceral reaction to a son who is now basically an alien. It’s all there, but it feels too unsurprising. The ending is also pat and predictable, but the story manages to earn its sentimentality for the most part, and gives us a realistic and moving portrayal of dementia. Philip’s memories of his world are also quite beautiful.

Nick Mamatas’ “North Shore Friday” gives us the recollections of George, who used to work for the INS in the 1960s, when they were reading minds using gigantic super-computers (and presumably still are using less gigantic and more powerful ones). George is of Greek descent, and tells the tales of his family’s adventures illegally immigrating into the U.S. under the thrall of the mind-readers.

A story with a strong sense of time and place, which strings along its somewhat cluttered narrative (made additionally cluttered by the presence of boxes with random snippets of characters’ thoughts). Mamatas sells the central idea well, using a specificity of language that effectively evokes the era and the subcultures he’s using. The sf feels almost incidental, which in this story is a good thing, allowing for a stronger suspension of disbelief.

Rudy Rucker’s “The Fnoor Hen” is a light, amusing concoction that throws biopunk futurism in with a folkloric style of storytelling where the stakes don’t ever feel too high. It follows a married couple, Vicky and Bix, who end up in an ownership war with Bix’s ex-employers over a “morphon muncher program” which leads to shenanigans involving a genetically engineered super-DNA devil-chicken composed of a reality-bending “fog of bio-gadgets” going rogue in their house. The story doesn’t take itself too seriously, which is good, because it allows Rucker to indulge in a kind of gonzo delight at its own chaos.

Christopher Barzak’s “Smoke City” might be my favourite piece in this issue. It’s a beautifully told, oneiric vision of one woman’s hell—“the city of [her[ birth”—which she sometimes visits in her sleep, only to spend years there with her husband and children, who continue to toil in this dystopic, industrial city whenever she retreats to her other husband and children in “the world above.” This is a subtle piece that gives no real answers as to why this Smoke City runs on the misery of others, or why she is allowed to escape while her family is relegated to suffering in the chthonic mills. It works more as a shifting, extended metaphor; an interpretive piece that becomes what the reader wills it to be. It could be about the woman’s guilt at her idyllic life, and the place such an ideal nuclear family holds in the webs of exploitation that underlie the capitalist system. It could be about her fear of losing that life, or losing her family. It could be about anything, and is.

Barzak gives us some lovely writing, immersing the reader in the dusky oppression of Smoke City and its mysteries: “Only fine dusty coatings of soot, in which children drew pictures with the tips of their fingers, and upon which adults would occasionally scrawl strange messages.” A story worth reading.

Esther M. Friesner’s “The One That Got Away” is another light piece to balance out the heavier ones. It’s also another period piece (set in the 1930s), showing us a snappy conversation between a black prostitute and an unusually shy sailor at a bar. More quirky fantasy than sf, though that depends on which angle you look at it from. We find out the fantastical trappings of both characters’ pasts. The exchange is entertaining, and has a screwball energy of its own. The story leaves the bar at the end, to deliver the punchline of its extended narrative joke, which is based on two pre-existing pop-cultural mythologies brushing up against each other, with the two characters representing each one. I enjoyed the story, even if it isn’t something that will likely stick with you for long. The punchline is actually quite disturbing if you think about it too long, though I’m not sure it’s meant to be.

Jack Skillingstead’s “The Flow and Dream” follows Bale, one of the few survivors of a colonization venture that placed its members in extended hibernation in their buried vessel under the watchful eye of an AI, Undertower (also called Ship), while the planet terraforms. The process is botched by the infiltration of an alien virus that wipes out most of the Sleepers, leading the AI to wake, as it were, and take action by directly communicating with Bale and demanding he go to the surface and fulfill the mission.

A melancholy story weighed with the burden of accepting our own fragility and mortality (significantly, Bale wakes an old man, having lost himself in the dream-state of “deep meld”) in the face of a hostile universe. Bale makes for a sympathetic and clear-headed protagonist, and his trepidation at the AI’s plan to put things into gear after years of disorienting hibernation is affecting: “Was it that he preferred it not work? Was he that afraid of living?” Undertower/Ship behaves in ways one would expect an AI to behave, but is also curiously likeable despite its unfeeling, damaging single-mindedness. Ultimately, it’s doing what it does because it wants us to survive, wants its creators to perpetuate themselves. The story ends up being about our resilience, and the resilience of our creations. Probably my second favourite of the issue.

An issue that maintains a certain standard, with all the stories exhibiting something of worth even when they fail in other areas.