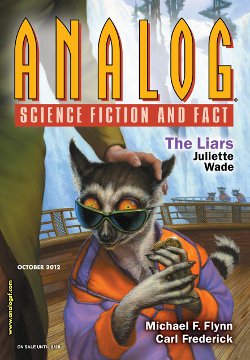

Analog, October 2012

Reviewed by Colleen Chen

I was impressed with this issue of Analog, which offers a nice range of stories—half taking place on future Earth, and half on other planets or, in the case of “Nothing But Vacuum,” on the moon. I found something thought-provoking and/or engaging in almost every story, and each one is intelligent, assumes the reader is intelligent (I confess I occasionally felt, while reading, that the assumption was wrong), and is written with incredible detail—truly professional work.

“The Liars” by Juliette Wade is the first of the three novelettes of this issue. Adrian and his wife are visiting Poik-Paradise, a world of “arboreal skyscrapers,” during a break before their next diplomatic assignment. The Paradise Company has created a tourists’ highly colorful and cutesified experience of this alien world. Immediately, Adrian gets a sense of a strange dynamic among the short, furry Poik creatures—some of them are “Slicks,” who emulate the way humans talk and dress, and then among them there are a few they call “Liars,” who are treated with a contradiction—ostracism and dislike mixed with a deference in providing everything the Liars want.

It is after Adrian meets a Liar named Op that he learns that she and the other Liars are missing a sense that allows them to communicate as the other Poiks do. They are half-mutes, able only to speak with throat-tones like the humans, “with heart-tones only to listen.” Adrian begins to understand the more sinister aspect of Poik culture as he witnesses a nightly ritual of gathering to sing to the Liars, to “honor and heal” them—but when he translates their song and sees, the next day, a tortured Poik in a tree-prison, he sees that the Liars are being hurt. He tries to find out why, and if he can do anything within the law of an alien culture to help Op before she becomes the next victim.

There are a couple of common themes in this story—the destruction of a culture by tourism, and the issue of how to respect the culture of an alien world even if one judges it to be wrong. These themes are woven into a unique and complex story that is visual and beautiful, tense and highly dimensioned. I love the world of the Poik that Wade has created, with all its social and linguistic details. The story leaves me with questions and a desire to read more about these characters I already care about; it would be great to see this story extended into a novel.

“Nahiku West,” by Linda Nagata, is narrated by Officer Zeke Choy, watch officer of the Commonwealth Police on Nahiku, a twin orbital with two city-towers that are connected by a long rail.

The story begins with the discovery that a man has a “quirk,” a physiological enhancement that allows him to survive exposure to hard vacuum. Although enhancements to humans are allowed, those that change human biology are illegal, and the man is executed. This event would have evoked no suspicion, except shortly after, Choy’s intimate Tishembra is reported for having a quirk. Choy warns Tishembra in time for her to remove it. He begins to suspect that someone tried to kill the executed man who had the quirk, and that same person was now targeting Tishembra; his suspicions grow when Tishembra’s son is attacked. Someone is discontent enough with the Commonwealth laws that they are willing to kill to get their point across, and Choy must discover who it is before someone else dies.

The technology in this story is alien enough to be fascinating, and the ethics that have developed around the technology show appropriate and plausible adaptations of technology to future culture. Decisions have been made by law about what modifications to human physiology can be made and have a person still count as “human.” “As more choices become possible, which ones should be allowed?” is the question posed at the beginning of the story, and at the heart of the mystery here is a discontent with what exactly the law allows.

The story is subtle, with plenty of action, and oddly enough, little actual change in the narrator’s awareness by the end. I confess some frustration because the story seems to imply that the laws are unfair, but the narrator is simply trying to find ways to live within their bounds, without disturbing them. But I suppose this is realistic, and it does create a story where no one can be judged as good or bad; they simply are as they are, complex characters trying to function within a society whose rules are flawed but attempt to address the needs of all.

In “The Journeyman: On the Short-Grass Prairie,” by Michael F. Flynn, Teodorq sunna Nagarajan the Ironhand is on the run, pursued by the brothers of the man he killed. We already should know he’s a hero by his name, but then we read this: “On all the Great Grass, he feared no man; but fearing a score of men was another matter. One Serpentine, he could meet knife-to-knife. Half the clan, maybe. But not all the Serps all at once. It would be a songbound feat even to evade them.” So now we really know he’s a hero.

We share Teodorq’s world intimately, his nights recalling lore of the sky that foreshadows later events in the story. We enjoy his ingenious ways of diverting pursuit, his skill in the kill when he is found, his honoring of those he kills by carving praise of their deaths on their chests. Then his flight brings him to the end of the Great Grass into a different land, that of the short-grass prairie. He follows a ravine up to an impassable dead end, then hears a strange voice coming from inside a fissure in the hill. He is joined by a Hillman on a walkabout who also has been seeing the rock light up. They enter the fissure, disturbed to see all signs of passage show entrance but no exit. The passage darkens behind them; inside the hill it’s much larger than it was outside, and then they encounter the ghost of something out of their own legends of the sky.

This story is flawless, with beautiful, lyrical descriptions and without a single wasted word. The story is also very funny once the Hillman shows up—because he says things like this:

“You plainsmen plenty fools. When Hillman want kill, he hide in bush, slay from behind. Higher success rate.”

I loved every bit of this story.

In “Ambidextrose,” by Jay Werkheiser, Davis is the sole survivor of the crash of a shuttle on a survey expedition of the mainland of an alien planet. He is from the planet’s Haven island, which has been sterilized and seeded with safe Earth life.

He wakes up restrained in a cabin, surprised to find that a human woman, Lyda, is surviving just fine on a part of the planet that has not been sterilized or seeded with Earth life. The island inhabitants had thought it impossible to coexist with the alien fauna and flora, as the vegetation is “wrong-handed” (sugars are right-handed and amino acids are left-handed, except on this planet, amino acids are right-handed and thus poisonous to the human body). But Davis is fed exobiotic food by Lyda, and he begins to learn that some food can be eaten when it combines both left and right-handed molecules. Still, even though he’s learning that he can eat the food, his life may still be in danger—those living on the mainland don’t want to be found, and they don’t want the colony on the island to go through with its plans to expand.

This is a strong story with themes that leap out and beg to be discussed. The island culture is mostly patriarchal, where women bear children and don’t work, and where the approach to the environment is one of domination, not coexistence. The mainland culture, on the other hand, is ruled by women; the females work, there is no marriage, and men are more nomadic. There, the people have adapted to the alien environment. “I enjoy watching the meteor showers on moonless nights,” Lyda says, and Davis answers—representative of the island culture—“I don’t often get the chance. The lights at the colony blot out all but the brightest of them.”

Davis and Lyda learn from each other; Davis sees that two ecologies can adapt and coexist, and Lyda sees that those she feared are just humans who can adapt and change—people who don’t need to be feared. The message is hopeful here, the story relevant and satisfying.

“Deer in the Garden” by Michael Alexander takes place in a future where the “Big Brother” of extensive security and monitoring of each individual’s movements is a reality. The story begins with a man named Wallingford in custody, and it intersperses a discussion between him and his interrogator with flashbacks of his extensive preparations for his intended crime—an attempt to disrupt the Northeast Information and Control Network. Like his colleagues, Wallingford is excellent at not being tracked—always paying in cash, changing his appearance, switching cars, doing practice runs of his sabotage. He is like the deer trying to get into the garden—where extensive measures are taken to prevent the disruption, as an alternative to shooting the deer.

The discussion between Wallingford and the interrogator puts a different spin on the old question of privacy and personal freedom vs. security. “I want to regain the freedom of individual choice, of the right to be just left alone,” he says.

The interrogator’s reply: “No, you want to return to a warm, halcyon past that is no longer possible. You talk about freedom but you are a contemporary rick-burner, a machine smasher. You desire options that are too destabilizing, too dangerous for the society you live in.” Reality requires compromise, she says, and better extensive security than an idea of freedom that requires everyone to have a gun and constantly watch their backs.

This story is sobering but very well done, presenting a future that is entirely plausible, a realistic extension of present-day trends. There is no indulgence of the fears that create dystopic images. I found it a bit of a downer—there is no black and white in this story, no good and evil, no paranoia and no ideals to strive for—there’s just a tired pragmatism and a necessary herding of the masses to be facilitated—just like real life.

“Reboots and Saddles” by Carl Frederick is my favorite story in this issue. Kevin Lee, a recent college graduate with a degree in electrical engineering, gets a summer job at his uncle’s vacation dude ranch. The indignity of being a junior riding technician—the person he’s replacing is 14 years old—is compounded by his uncle’s rule that only the special CX1-Cybersaddles are to be used. These high-tech, gear-shifting saddles, which act as an electronic interface between rider and horse, make riding as easy as the turn of a handlebar and the push of a button.

The trouble, and the fun, begins when colleague Shane takes a group of elderly riders out towards the Grand Canyon. The saddles malfunction; the horses become unresponsive to any commands, continuing at a slow walk directly towards the Canyon. Shane calls Kevin, and they race against time to try to stop the horses’ progress before they and their riders (apparently too fragile to easily jump off their mounts) plummet to their deaths.

I loved this story! It was engaging from the start and got better with every paragraph. The dialogue sparkles and is just as visual as the descriptions. The story is completely satisfying from start to finish, combining elements of science, some horses, suspense, visible character growth, and a number of laugh-out-loud moments. The characters, from disgruntled Kevin to the horse who loves Fig Newtons to even the perpetrator of the sabotage—are all endearing. Great stuff!

“Nothing But Vacuum,” by Edward McDermott, begins with a rocky landing in a crater on the Moon by three astronauts. Out of sight of the Earth, they are receiving no radio transmissions. The ship is banged up, without enough propellant to achieve lunar orbit or return to Earth. The prospect of a slow death in the midst of the vast vacuum of space, unable to communicate last words to loved ones on Earth, is what they now face. They brainstorm ways to signal Earth, with little in the way of resources, forcing them to get creative.

This is one of the shorter stories in the issue, and it packs a heavy dose of atmosphere in a small space. It taps into primal fears we have of losing some very basic things we take for granted—like air, and contact with other people and our planet. So it’s powerful and creates a strong identification with these three astronauts, who show through their choices and attitudes a courage that is truly moving.

“The End in Eden,” by Steven Utley, has a somewhat unique structure—it consists mainly of dialogue, a mystery solved through conversation. Paleozoic biological specimens have been smuggled from the past across the space-time anomaly. Some quirky Customs agents get involved in trying to solve the mystery. More than half the story is a discussion of which government agencies have an interest in the issue, and then they narrow down the suspects of who initiated the smuggling and go after who they think did it.

I had to read this story three times to understand what was going on, and even now I’m not sure I do. I still feel like I might have missed something, because there’s almost no apparent plot and the end felt anticlimactic to me; some of the dialogue is clever, but maybe too clever, because I feel like it went over my head. I hesitate to judge the story negatively because there was nothing badly done about it—I just didn’t “get it.” No doubt other readers will.