Analog, November, 2014

Analog, November, 2014

Reviewed by Louis West

“Flow” by Arlan Andrews, Sr. is the tale of Rist, a young man from the far icy north, who decides to see the warm lands of the south by riding a calved iceberg downriver with a crew that harvests ice for sale. What he finds is all new: cities, people much taller than his own, technology wrested from before the time when the gods warred over the world, people of many different shades and hair color, a harsh religion that burns disbelievers at the stake, and a clear sky filled with the sun, moon and stars in contrast to the dim mist that crowds the sky in the far north. Rist records everything on a hand-held totem to return to his father, the ruling Tharn of the north. He seeks to discover opportunities for his family and people to learn new ways to better their lives by mastering the technologies used by the south. To such an end, he steals a spindle of mono-filament-like spider-web material from the old times used by the southerners. But the priests suspect him, and he must flee for his life, eventually heading even further south to the end of the world where the river plunges over a massive waterfall. Down, not back, is his only recourse, and so ends the tale.

This reads like a blend of post-apocalypse, throw-you-in-the-fire-if-you-transgress Dark Ages religion and young Turk barbarian grows to manhood by venturing into strange lands where he marvels at all the strange, new wonders, then acting rashly enough to almost get himself killed. Telling abounds. Every time Rist discovers something new, there is a fellow berg-man nearby to conveniently explain it all to him. There is little actual action-driven discovery, even during Rist’s flight south. Disappointing. At least his world-view evolves the more he experiences. Except the story doesn’t end, it just stops. Perhaps this is a part one of two?

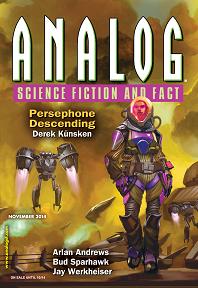

Derek Künsken’s “Persephone Descending” is a well-researched, highly suspenseful hard SF tale about Marie-Claude’s fight to survive in the lethal atmosphere of Venus. After inspecting a high-atmosphere factory, Marie-Claude’s Venusian transport craft is attacked by a sabotaged maintenance drone as she takes off, and she has to parachute into the increasingly acidic atmosphere in order to escape the pursuing drone. Much like the movie Castaway, Marie-Claude has to discover how to utilize what’s in the environment around her to remain alive. In this case, it’s using the various types of floating extremophile colonies to shelter from the drone, to replenish her oxygen, to recharge her suit batteries and eventually destroy her pursuer.

Marie-Claude’s descent into the Venusian atmosphere is akin to a descent into the hell of Venus which, in this story, is cast as Persephone, the goddess of the underworld, of nature, of death and rebirth. While her personification has been evolving since before the time of Minoan Crete, Persephone is essentially the all-pervading goddess of nature who both produces and destroys everything. Even though she gives life to the extremophiles, she hates the colonizing Terrans “with blinding sulfuric acid, biting cold, ferocious winds and, if they were foolish, with crushing pressure and melting heat.”

In addition to the excellent science and the edge-of-your-seat battle to survive, this tale is also cast in a future time when an independent Quebec seeks to make its mark on the solar system by colonizing Venus. As a result, the characters and politics all reflect the vicious conflict between those who want an independent Venus and those who wish to remain part of a greater Quebec.

Loved the extremophile lifeforms, the all too possible politics and Marie-Claude’s unrelenting battle to survive. Kudos to the author. Highly recommended.

In “Superior Sapience,” by Robert R. Chase, Mr. Bennett runs a facility (“Superior Sapience”) that manages autistics, by using a cocktail of drugs to refocus their obsessive focus toward different topics, thereby creating individuals with superior problem solving abilities. These people are then leased to businesses and politicians to solve difficult problems. Originally hired to run HR, Bennett uncovers abusive behavior by the facility’s manager towards the autistics, leading to increased suicides. Fired for insubordination, then rehired to replace the manager whom the company’s owner fired, Bennett is now in charge of everything.

The company’s future is at risk due to a Chinese government funded competitor that is underpricing the business. Consequently, the company’s owner is desperate to bring new, leading-edge solutions to the marketplace. Soon after being rehired, Bennett learns he’s become an involuntary human guinea pig for an intelligence and immune-system enhancing drug, developed based upon side effects from the drug cocktail used on autistics. Trapped by arcane details in his work contract, Bennett reluctantly agrees to go along with the trials. After weeks of treatments, his IQ rises a little and his health improves, but nothing dramatic. Meanwhile, he learns that the company has actually discovered a cure for autism but keeps its patients deliberately autistic in order to provide skilled problem solvers to the world. Bennett confronts the owner, the augmented autistics at the Chinese competitor revolt, taking over the company and freeing their nation from its Communist rulers, and all is wonderful. The end.

The story is dense with heavy scientific material and possible science, which I enjoyed, but was all too often described through contrived telling scenes that dramatically slowed the pace of the tale. Bennett is somewhat interesting as a protagonist, but the tale lacks much in the way of actual tension. I never understood the purpose of having him as an involuntary guinea pig other than it gives him the opportunity to study the company’s internal documents thereby learning about the cure for autism. The final conflict with the owner jumps out of nowhere like a crime thriller that reveals all only at the end, and the final scene is a kind of “they lived happily ever after.” Although an excellent premise with a serious let down, you may still enjoy it.

In Ian Creasey’s “An Exercise in Motivation,” Marla is hired to teach the Entia, intelligent computer-software “entities,” to become self-motivated. Evidently, regardless of how smart they are, they lack any self-drive, especially to discover answers to questions humans have yet to ask, i.e., to find truly new knowledge. As she studies the Entia, she wonders how much of their lack of motivation is due to their creator’s desire to protect them. She attempts to get their creator to see her point of view, but fails, then she returns to her own meaningless, drab existence to ponder what to do next.

The story lacks any tension, and starts with a bad caricaturization of what a computer scientist would be like. It’s also filled with lots of side-note telling. Dull and uninteresting. I can only conclude that the author did not have enough motivation to find answers to the questions he raised in his story.

“Habeas Corpus Callosum,” by Jay Werkheiser, explores the consequences and social backlash when immortality treatments make life imprisonment “cruel and unusual treatment.” Jared faces the prospect of his lawyer getting his “life in prison” punishment overturned since he’d been judged before the life-extending treatments had become available. Freedom certainly has its allure, but he wonders if he’ll ever be free of his own demons birthed by his horrible rape and murder crime. In particular, the face of the mother of the girl he killed haunts him every night. Ultimately, he decides that living forever with that image burned in his brain is just too much for him. A solid, well-focused tale. Recommended.

Bud Sparhawk’s “Conquest” is a cute tale about a commander trying to intimidate the rebels of EpsEran into surrender with his Conqueror Class warship. He uses a new star drive to get to his target ten times faster than could prior star drives. Except the journey actually takes 300 years. He arrives with Earth no more, surrounded by warships much larger than his own, and a bevy of customs officials demanding a full accounting of all he carries to ensure that proper taxes and fees are levied. After he exhausts his angry bluster, he realizes that he does have one option worth his while. Fun and recommended.

“Elysia Elysium,” by V.G. Campen, is a story of new beginnings in a world struggling to rise from the chaos and loss of knowledge caused by two world famines. Eli is a scavenger, venturing outside the remains of old Atlanta to gather herbs and artifacts from before the famines. His mentor, Old Cal, is dying from skin cancer brought on by the particularly virulent direct sunlight. When Eli visits Cal at the hospital, Cal convinces Eli to deliver a package to a place near the sea, a secret location only Cal knows. There Eli learns how humans have been learning to successfully implant chloroplasts under their skin in order to survive without eating, thereby being more able to learn and rebuild civilization.

There are some interesting ideas in this tale but limited tension and little challenge to the protagonist. Everything came too easily to Eli. Disappointing.

In “Mercy, Killer,” by Auston Habershaw, Virgil is an attorney hired by Mercy, an AI, to defend “her” against multiple charges of killing other AIs, 52 in all. Virgil doesn’t really want to represent the AI, believing her to be guilty as charged. However, she tells him that there is a clue that my exonerate her, but it is hidden, even from herself. The only hint she can offer is a quote from the 6th century Roman philosopher, Boethius. Once back home, Virgil is messaged by an unknown entity, a message his advanced firewalls cannot stop. He eventually answers the message and finds himself drawn into a VR world with a fragment of Mercy that takes him deep into AI realities. In truth, AIs are not hyper-intelligent and experience the same foibles as humans. While they generally love their human creators, they fight brutal battles among themselves for control and conquest of the internet Cloud. Mercy wants humanity to know this before the exponentially growing population of millions of AIs engages in a total war which will destroy human civilization.

Interesting premise, pathetic protagonist (Virgil) yet loved Mercy as the co-protagonist. Overall, the story raises some sobering ideas. Recommended.