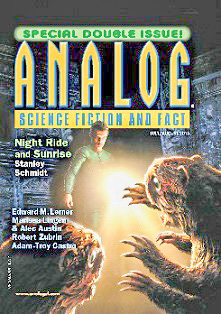

Analog, July/August 2015

Analog, July/August 2015

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

This Analog double-issue presents fourteen original short works including a novella and two novelettes. (The SFWA says a novelette’s word count exceeds 7500 and a novella’s exceeds 17,500.) Choose between the light and comic, or the dark and dour – pick from a range that includes hard SF and unabashed fantasy (“Cease and Desist”) – and read about love or else people incapable of love. The fourteen stories surely offer something for any reader’s taste.

Adam-Troy Castro’s “Sleeping Dogs” opens on an alien ocean teeming with dangerous life the “old man” protagonist hunts with skill that makes him seem as oblivious to danger, an action hero striding through a building full of mooks. The world of Greeve looks low-tech at first, but it’s had no post-colonization tech loss; the protagonist cleans his kill with an “energy blade” and a young orphan rides what sounds like a flying motorcycle to give him news – in a local patois, then in an interplanetary business language. The local lingo entertains, as readers imagine words’ etymology. It’s an interesting backwater world, and feels like the place an old spook like the protagonist might pick to hide in retirement.

But the protagonist is an old spook, so what are the odds he gets a calm retirement? That worry sets him on the trail of newcomer offworlders, entangles him in their affairs, and runs him into what may be completely unnecessary danger. The stakes – freedom and his long-deserved peace – are perfectly clear, and the characters’ decisions easy to understand. The story provides a fairly long setup for its last-page twist. Hard-SF fans who demand stories require their tech form an integral part of the story may be disappointed the tale could be repainted in medieval dress without harm to its result or message. Readers who like a tragic turn – or thrill to see the old sheriff strap on his guns one last time – may find the ending very much to their taste.

“The Smell of Blood and Thunder” is Liz J. Anderson’s comic SF novelette about a veterinarian’s house call to a planet of intelligent dogs and cats (with intelligent fleas). Meddling with other species’ intelligence (and diet) only worsens traditional dog/cat rivalries, and the vet/diplomat sent to sort out the quarantined planet’s problems ends up with her hands full. Mediating a dispute between dogs and fleas proves no better than mediating one between an angered townsfolk and its nest of vampires. The promise of a technological happy ending prevents readers from reading into the story some kind of message about intractable real-world conflicts, which technology traditionally only worsens, and which tends not to show a happy ending in plausible sight. The story’s SF elements could not plausibly be removed without damage to the plot, but the treatment of genetic engineering is lightweight enough the story could as easily be recast in a fantasy world where the intelligence and diet of future generations could be manipulated by wizards. Anderson’s light and humorous tale feels especially suited to anyone with an interest in the dog/cat debate.

“The Tarn” by Rob Chilson opens on the leader of a community watching its population’s exodus to join a treasure hunt. The characters’ unusual names and the weird beasts that pull their conveyances convey a sense of alienness. On the other hand, property records and attorneys filing documents regarding contract rights seem to make the aliens familiar. They count in base two, but use tricycles: different and similar at once. As the story develops, it seems the world is populated with whatever was left over from the civilization humans created before it cratered.

The main character’s stakes and motives seem unclear long enough that holding out for insight gets to feel like work: his slow interrogation of witnesses doesn’t convey the sense of risk that rivets attention in detective novels, though the story dedicates several pages to the mystery of the locals’ sudden urge to leave town to hunt treasure. For the first dozen pages or so, their mission seems a snipe hunt. When things start happening, it’s no result of anything the main character does. His suspicions and efforts seem, in the end, to have no impact on the story’s outcome. The story has an ironic ending, which one may easily enjoy. The main character develops some heart, which is something – characters are supposed to change – but readers who require a traditional story structure climaxing in a character-defining decision will not find it here.

“Breakfast in Bed” by Ian Watson is a fantasy set in a couple’s bed. An anomaly – looking like a glitch in the Matrix, but possibly evidence they’ve changed universes – opens the tale. The bulk of the story consists of a conversation interrupted by sex. Since we know little of the characters and their motives beyond the fact they share work as journalists and share an interest in science, it’s hard to get invested in their detailless, tension-free sex and the woman’s naked walk to the kitchen. The piece appears to have no conflict, only the question of what explains the glitch. In dialogue occasionally interrupted for action devoid of tension or conflict, the characters speculate what explains the male character’s observation. The story-ending decision – in which, they successfully imagine the Universe different, only to discover (among other things) that their bank account balance has improved dramatically – smacks more of fantasy than SF. Readers who want to read about two geeks discovering physical and emotional intimacy would do better to try Ada Lovelace’s Geekrotica novellas, which don’t offer any more SF than “Breakfast in Bed” but provide much more enjoyable Star Wars references than one mention of a “Lego Star Wars” duvet cover. I give full marks to Watson for recognizing that readers want to enjoy unabashed geeks unafraid to nerd out in front of each other, but stories aren’t really advanced by sex that has no impact on characters or plot, or by female nudity that provides only fan service. It’s too tame for a good Penthouse letter and too thin on story for something weightier.

Marissa Lingen’s and Alec Austin’s “Potential Side Effects May Include” offers a research study participant’s view of her near-future Boston as viewed through the eyes of someone with an implanted computer whose software releases fear-inhibiting chemicals to promote a stress-free life. Paralysis thinking about student loans? Worry about calls from nagging parents? Not a problem, until the software crashes. The story explores the downside of reducing fear and suggests dark applications for the technology. It’s a wonderful example of SF exploring the effect on human life of future technology one can imagine really existing: hard SF. The tale is a bit light on the protagonist’s climactic decision, but it offers a thoughtful glance at a handful of problems involving human-subjects research ethics. It doesn’t offer a heavy-handed criticism of meddling with the human mind – the upside of controlling stress and the benefit of effective treatment of depression are both laid out for readers before a negative view can be formed – but urges thoughtfulness without preaching a conclusion. It’s an enjoyable short read.

“In the Mix” by Arlan Andrews, Sr., is a two-page short set in a future whose Internet bandwidth carries not only text and images but smells and emotions. Participant/users experience firsthand – and instantaneously –occurrances in other lands. Amidst such immersive instant gratification, text-based entertainments are a lost art, largely inaccessible to a future culture whose participants can mix their experiences and emotions for others without need of letters or punctuation. It’s a dark future, but the conclusion offers some hope for the written word and its classics. “In the Mix” sketches a world and its problem neatly and quickly to provide in few words a story that depends on its SF elements throughout – a shining example of short SF.

Jacob A. Boyd’s “Guns Don’t Kill People” opens on an intelligent rifle uncased on an alien world after a year of disuse. Required on penalty of deconstruction to allow only lawful kills, the rifle pours through data sources – only to find some of the data on which it would rely has been corrupted. “Guns Don’t Kill People” combines vat-grown humans’ rights and artificial intelligence to create a mystery that survives the future’s ubiquitous surveillance. It’s not an expected environment for a love story, which is all the better. With respect to the gun policy debate so bluntly referenced in the story’s title, the author asks whether making weapons smart enough to make their own decisions will make the process any less subject to the kinds of weighing, games, and uncertainty that surrounds violence in the current era. It’s a fun piece, offers twists well suited to an AI story, and ends on a higher note than hinted by the opening lines.

In “Pincushion Pete,” Ian Creasey offers a look at a man born intellectually disabled who, using modern interventions called “patches,” has become an intelligent and articulate force against prejudice against persons sharing his disability. Unfortunately, he is accused of being a “patch” manufacturer shill and becomes a magnet for criticism of the class of interventions with which he has changed his life – undermining the work he does against prejudice. Creasey delivers a world with real-feeling political tensions surrounding the developing medical interventions and the people they are intended to help – and those that cannot as yet be helped. The SF elements are an integral part of the world and its conflicts, and feature in the character’s eventual choice how to live his life in the face of public criticism he’s “addicted” to “patches” designed to improve his brain function. The story certainly raises more questions than it answers – what interesting short story doesn’t? – but it provides a satisfactory answer for what Pete himself decides to do about the criticism directed at him. “Pincushion Pete” is an interesting look at a problem that has echoes in real-world problems, and invites readers to consider ethical and moral concerns that touch on issues they can find here in the present day. It’s a fantastic use of SF, and worth reading just to digest the problems posed Pete.

Ron Collins’ “Tumbling Dice” combines a casino heist (complete with confederates and betrayals), a love story, and a dream about normalcy, with themes of fate and addiction. An inveterate gambler and a genetically aberrant femme fatale who can’t turn off her come-hither collide at a craps table, each playing a different game. It’s a fun run through the schemers’ schemes, to see if they make a pair when the dust settles. The motives of the female lead and the method of scamming the casino are both intertwined with SF, and there’s interstellar travel, but this story is really about people – the fluke of attraction, and the decision whether and when to trust. Enjoyable all the way through.

In “Dreams of Spanish Gold,” Bond Elam depicts a world like our own, but protected by robot guardians in whose care our ancestors left us, but whom modern humans no longer remember. The action begins when the robot adopts the persona “Jose” and a human likeness to get a sense what it’s all about. It’s a four-page story, so the only character we really get to know is the protagonist – whose whole motivation derives from his lack of insight into humans, so it’s little surprise that through his eyes we see only two-dimensional depictions of those about him. Without giving away the title’s connection to the conclusion, “Jose” begins his search for humanity by looking for love and discovers all too quickly what it means to be human. There’s a symmetry in the characters’ pretense the author didn’t need to include, but speaks to the insight he has his protagonist derive in the climax: humans aren’t the only fickle, inconstant, misbehaving liars in the story. “Jose” himself isn’t really named Jose – isn’t even human – when he sets out to seduce Rebecca on his road to discover humanity’s meaning. Indeed, to prepare himself he violates instructions about the privacy of dreams to give himself an edge in his efforts. Apparently what it means to be human includes how someone – having betrayed clear ethical standards and intentionally deceived every person in one’s life – could nevertheless manage to imagine one’s self the victim when things turn out differently than hoped. Elam suggests humanity is more than the capacity to suffer heartache – it’s the capacity for conviction, despite being so obviously the story’s villain, that one is in fact the victim in all that occurs. It’s a darker view of the world than one expects a robot to discern so quickly – and maybe the robot only sees its own heartache, after all. But we can certainly enjoy Elam’s dark vision and the moral decay of our superhuman protectors.

“Dreams of Spanish Gold” offers a robot protagonist, but nothing else in the story suggests a future world or an alternate universe. Had the story involved a golem or a Fae instead of a robot, no need would exist to change the plot. The story is really about people rather than technology, or the relationship between people and technology. Readers who don’t want to read about the fickle hearts of young people may not find this to their taste, or argue it’s not SF. I believe it’s important the protagonist be a genuine outsider of some kind in order for his curiosity to feel innocent and his start-of-story conduct not to look evil and stalkerish: he’s on a noble quest to learn what it means to be human – at least we need to believe that as he does long enough to accept his excuses until we realize he’s no better than those he’s there to protect.

“Ashfall” by Edd Vick & Manny Frishberg opens during a volcanic eruption that threatens both a population of natural bees and the caravan-dwelling family’s collection of artificial bees used in their crop-pollinating business. When the artificial bees assist natural bees experiencing trouble with ash, the first assumption is that a human has reprogrammed the bees. Well, no. “Ashfall” is a developing-AI story that adheres to the loss-of-human-control trope without threatening mortal enslavement by machine superiors. The hybrid colony of natural and artificial bees may be comprised of members with barely enough information processing ability to do their jobs, and the combined colony’s behavior proves even more complex than a natural hive’s alone, but at the end of the day the thing they know how to do is to pollinate flowers. It’s a fun idea, and it’s nice to see a disaster averted, but there’s no hard choice forced on a protagonist. The strength of “Ashfall” is its concept, not its story. At about five pages, it’s not a long journey, and if you like a happy ending this may be just what your programming requires.

Bud Sparhawk’s “Delivery” provides a dark-comic take on the future of online shopping from a vendor with effective data-mining software. Its near-future setting is so close to existing capabilities and practices that it’s almost not SF at all. Doubtless inspired by real-world data-mining projects designed to send customized coupon collections to specific shoppers (including the famous Target coupons that proved the store deduced a teen’s pregnancy before her father), “Delivery”’s vendor actually ships products it determines customers are about to need. The unnamed vendor isn’t dark or hostile, and happily offers to take undesired items off the shopper’s bill. When the shopper learns from a gushing customer service representative that the vendor’s algorithms are designed to predict needs based not only on past purchases but on weather forecasts, and keep an eye on politics, it’s pretty obvious what dark path the upbeat piece is about to take. Sparrhawk’s “Delivery” is too funny for its length to skip.

Tom Greene delivers “The Narrative of More” in the old style of a historic explorer’s account, inverted to show a far future of deep space fleet’s contact with “indigenous” locals who lost their human ancestors’ technology. The narrator recounts the effort to plumb the mystery of the locals’ persistent refusal to cooperate with each other enough to make anything valuable, build anything permanent, or aid another in the smallest endeavor. The narrator – called “More” by locals looking for handouts – shares the frustration experienced while attempting to shape the populace into something that might be taken for a functioning society. By the time More learns what significant efforts were required to reduce humans to the awful state found on the colony planet, one wonders what possible utility interacting with the inhabitants could have. The story’s point is apparently to demonstrate how cooperation and empathy are crucial to every aspect of society we find laudable, and to disgust the reader with the kind of existence is suggested by a purely self-interested population incapable of trust. Greene suggests that all the ennobling virtues in the world are lost on a people who don’t value them. It’s a dark future.

Jay Werkheiser’s “Cease and Desist” is a time-travel comic fantasy that opens on a lawyer delivering a nastygram from his client to his client’s past-self. Hilarity ensues. Courtroom drama; an appeal. To say more risks spoilers. Two pages of chuckles.

C. D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.